One of the things I’ve missed since acquiring my Brompton bicycle a few years ago is a way to carry a water bottle: there’s no standard water bottle, mounting bracket, and, because the bicycle folds, any solution, ideally, can remain in place when the bicycle is folded.

I’d read all sorts of reviews, looked at Amazon products, etc., but I never found something that looked like it would work.

Last month, however, Lisa and I were in Islington, a London neighborhood, where we were looking up one of her old haunts, and going to an excellent art supply store. On our rainy walk from one place to the other, I spotted a Balfe’s Bikes, and popped in to ask what they’d recommend.

They only had one suitable accessory in stock, a made-in-the-UK Restrap City Stem. I tried it out with Lisa’s water bottle, and it fit nice and snugly. I liked the design, and the method for attaching it, and how it would survive the fold, so I bought it.

I got a chance to try it out last week on an unseasonably warm late fall day.

Here’s the Restrap holding my water bottle on the unfolded Brompton:

And here’s the Restrap, still in place, on the folded bicycle:

It worked exactly as advertised, and I enjoyed ready access to water as I toddled around town on my bike running holiday errands.

I got an email this week from Doug Bridges at Provincial Credit Union, announcing his impending retirement.

I’ve been a credit union member for coming up on 32 years; Doug has been an important go-to contact there for the last 26 of those years.

Truth be told, I’ve never known what Doug’s actual job title was; his email signature on retirement was “Community Development Officer,” but I have always thought of him as “person to talk to about the credit union, and how it could be better.”

When I look back at my email exchanges with Doug over the years, I see subject lines like:

- Solution to Banking Problem?

- Connect my account with my brothers?

- Downtown ATM?

- Language Selection

- Currency Exchange Rate

- Question about MemberDirect

- Printed Statements for Personal Accounts

- Foreign Withdrawls

- Traveling in Europe

In other words, a little bit of everything. And Doug has was always quick and ready with a helpful reply, bringing truth to the notion that we are members of the credit union, not merely customers.

It was only this fall that I realized that Doug’s father was the late, great Vance Bridges. Vance was a force in the coop movement, and he brought the same spirit to his coop dealings with me that Doug brought to our dealings at Provincial.

Best wishes on your retirement, Doug: you will be greatly missed.

The EP The Chronicles of Gerald Womack, from The Man The Myth The Meatslab is some kind of wonderful. From a TikTok about the album:

Hey I’m

The Man The Myth The

MeatslabI wrote this ep over the last few months and now it’s out there in the world.

I made it with an old

microphone I bought on eBay for £20.Its a project born from following what lights you up.

Trying to stay true to your North Star and writing songs that feel like a soundtrack to life past/future and present.It’s been absolutely amazing to see these songs through your eyes on here and soundtrack your small beautiful moments.

Im truly grateful.Then you grow old

Talk yourself down

Make yourself up

Do yourself proudLove tmtmtm

I missed this when it was published in 2020: Paul MacNeill interviewed Fred Hyndman about his uncle, the businessperson and philanthropist Robert Cotton. From the transcript:

Robert L. Cotton was a quirky, bowler hat wearing World War I veteran with a strong aversion to sending his hard-earned tax dollars to Ottawa. By trade, he was a contractor who brought the rent-to-own concept to PEI, allowing hundreds of islanders to own their first home. But it’s what he did with his money that stands the test of time. During his lifetime, Bobby Cotton established trusts, which in today’s dollars would be valued at more than 13 million dollars.

“Annual proceeds have funded everything from scholarships at Holland College, construction of the Sheraldown Boardwalk, development of the former provincial tree nursery in Bunbury, provincial parks in Broodnell and Stratgartney, Confederation Centre Art Gallery, and hundreds of community projects over the past 50 plus years. There should be a statue to Bobby Cotton. So immense is his contribution to island life.

The Cotton Trust for Public Parks remains active, funding efforts to acquire and develop parkland across Prince Edward Island.

The episode is one of the Because Life is Local podcast from (RSS), which includes episodes with Dennis Ryan, Doug Griffiths, and Dennis King. The show, alas, appears to have gone into hibernation.

I love this paragraph from the CBC story Vet college suggests its MRI could shrink the wait times for P.E.I.’s human patients:

Griffon said the AVC needs to build a reception area for human patients, so that they don’t have to use the same entrance as dogs or horses.

In a recent episode of The Knowledge Project, storyteller Matthew Dicks was asked “What’s the difference between a good story and a bad story?”. Part of his reply:

So a story is about change over time. Usually, it’s sort of a realization.

Like, I used to think one thing, and now I think another thing. That’s most stories. Sometimes they’re transformational, meaning I once was one kind of person, and then some stuff happened, and now I’m actually an authentically different kind of person.

Five years ago today I wrote this to family and friends in a newsletter about my late partner Catherine’s cancer:

Catherine is by no means at the end of her treatment options, but it’s clear, both from empirical evidence and from Dr. Corbett’s demeanour, that she’s entered a new act of this play. Meaning that, if you were planning to nominate her for a Nobel Peace Prize, I’d start assembling your paperwork (they take forever to process things).

But she is not on death’s door.

It turns out that Catherine was at death’s door: 6 days later she decided to suspend treatment for the holidays; 11 days later she was admitted to hospital with a hip socket fracture; 16 days later she came home for Christmas; 24 days later she was back in the hospital, in a morphine-induced delirium; 41 days later, she died.

When Catherine was diagnosed with cancer, in the fall of 2014 I was, in Matthew Dicks words, “one kind of person.” I remained that kind of person for the next six years. I was that kind of person when she died, and for a long time afterward.

Some things about that kind of person:

I was afraid, but unwilling to admit it.

I was desperately lonely, but unwilling to admit it.

I thought I could control chaos by writing about it, that a dose of distracting levity could pierce any bad news.

I thought my job was, at any cost to myself, to prevent calamity, to contain, manage, anticipate.

I saw vulnerability as a weakness, a third rail to be avoided.

I had a long list of things I wouldn’t talk about, had never talked honestly about: death, sex, money, what I wanted to be.

I was angry. And anxious.

I was anxious almost all the time, in a state of hypervigilance, unaware that I was. I thought it was normal to feel that way: brittle, at the effect of everything.

And then “some stuff happened.”

For the longest time I thought the “stuff” was Catherine’s illness and death. I thought that was the inciting event for an internal realignment, that the experience changed me.

But the truth of the matter is that on the day she died, and for months after, I was the same afraid, anxious, hypervigilant, angry, impenetrable person. Watching your partner wither and die is hard, desperately hard, the hardest thing I’ve ever been through. But the experience, in itself, did not change me.

Two years later I met Lisa, a magical sliding door connection that we are celebrating the third anniversary of this week.

It is tempting to credit our meeting, our connection, as “the stuff” that happened, the gateway to a fundamental change.

While there is no doubt that our partnership is deep, connected, vulnerable, vital, I’ve come to realize only lately that I haven’t changed “because of Lisa,” but rather that change within me has allowed me to be the person I am in relationship with her.

I read this recently, about how relationships evolve from the initial heat:

There has to be some maturing, some settling, some turning inward toward resources that lie within yourself, rather than outside of yourself.

That turn toward “resources that lie within yourself” is the “stuff that happened” to me, a gradual process of unburdening myself from the mantle of control, contain, protect.

I have had help in reaching inward, from family, friends, therapists, and, most notably, from Lisa herself, who so values introspection, and who’s modelled so much that’s helped me evolve.

But I did this. I am doing this.

“And now,” as Matthew Dicks described it, “I’m actually an authentically different kind of person.”

Some things about this kind of person:

I’m still often afraid, anxious, stirred up, distracted. But I have ever so slightly more mindfulness, so that, some of the time, I can see this happening. “Oh, this feeling is me being anxious.”

I am no longer lonely. Yes, I am part of a loving partnership, one that feeds me every day. But unleashing the desperation of loneliness was something I needed to do before I met Lisa.

Writing is still valuable, therapeutic, but trying to use it to obscure the darkness doesn’t work. I know that now.

I’m getting used to the idea that no amount of preparation and vigilance will prevent calamity. I’m getting better at living without control.

I see vulnerability as a strength, a necessary precondition to living a full life. It’s still scary. I still run from it more often than I like. But as I step forward more often, take risks, tell my truths, express my needs, it becomes self-reinforcing. I’m learning that being more authentically me won’t turn me to dust.

Death, sex, money, what I want to be: I am so much better at talking honestly about these things.

I’m still angry. And anxious.

But I’m not anxious all the time, and I’m no longer in a constant state of hypervigilance.

What underpins all of this is a fundamental agreement with myself to no longer live life at the effect of others, at the effect of events I cannot control, to realize that all that I need is inside me, and always has been.

I cannot sufficiently describe how freeing that has been, continues to be.

Lisa and I returned from a two week vacation on Monday, a trip, by ourselves, to Tallinn, Helsinki, and London.

While those cities were fascinating and magical, each in their own way, what I take from our time away, what will endure, is the opportunity to pause and feel the depth of our connection, to explore its vulnerable edges, to feel the lovely, squishy, chaotic feeling of being more ourselves with each other than we’ve ever been before.

What a gift it was.

During the three years Lisa and I have been together, every night, as we lie beside each other in bed, after we’ve talked about our day, settled into the warm snuggle, every single night I have a feeling that washes over me.

For the longest time I didn’t understand this feeling, I didn’t know what it was; I tried to take it apart, analyze it, come to terms with whether it was okay to feel it.

What dawned on me only recently: the feeling is happiness.

How wonderful is that.

And how wonderful is it to realize that the capacity for happiness, for connection, for joyful vulnerability with another, that was always there: I just needed to find my way toward it, to let go, to allow it to emerge.

I’m so excited to find out what comes next.

Artist Keith A. Pettit, interviewed in Handprinted:

About 20 years ago, I shifted my focus from sign making and graphic design, to an art-led living. I range from tiny wood engravings, lino reductions, and sculptures; usually using wood to create — from the reasonably small to the stupidly enormous. Sometimes they’re also on fire.

I like the phrase “art-led living.” We’d all do well to live like that.

Last month I took at Nonviolent Crisis Intervention course at Holland College. It was training I’d wanted for more than a decade; this was the first chance I’d had to take it locally, and it proved invaluable. I grieve the years I was without it, and handled crises ham-fistedly.

One of the slides in the course slide deck concerned the Johari Window, which looks like this:

The idea is that you choose a number of adjectives from a list to describe yourself, then have your peers choose adjectives to describe you, from the same list. These adjectives are then placed in the quadrants based on whether each appears on both lists (“Arena”) or one or the other (“Façade” or “Blind spot”).

We didn’t dwell on the concept, but once I got home I looked it up. Who was “Johari,” I wondered?

Johari, it turns out, were Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham, American psychologists.

As things often happen with me, I hopped into the Johari rabbit hole, and discovered that Luft died in 2014, two days after he turned 98 years old, after being hit by a car:

In a statement Saturday, his family said, “We are mourning the loss of our father and family member, but we are also celebrating his long and healthy life. Joe was the child of immigrants, a World War II veteran, renowned psychologist, proud father of four and beloved local figure. He cherished his daily walks and took them religiously for over 50 years.

“While his death was sudden, he died doing what he loved. We do not yet know the details of what happened, but our hearts go out to the driver of the car and his family during this difficult time.”

Nine months later, the city of Berkeley installed a flashing beacon at the intersection where Luft was killed.

I have thought of Luft often in the month since I came to know of him.

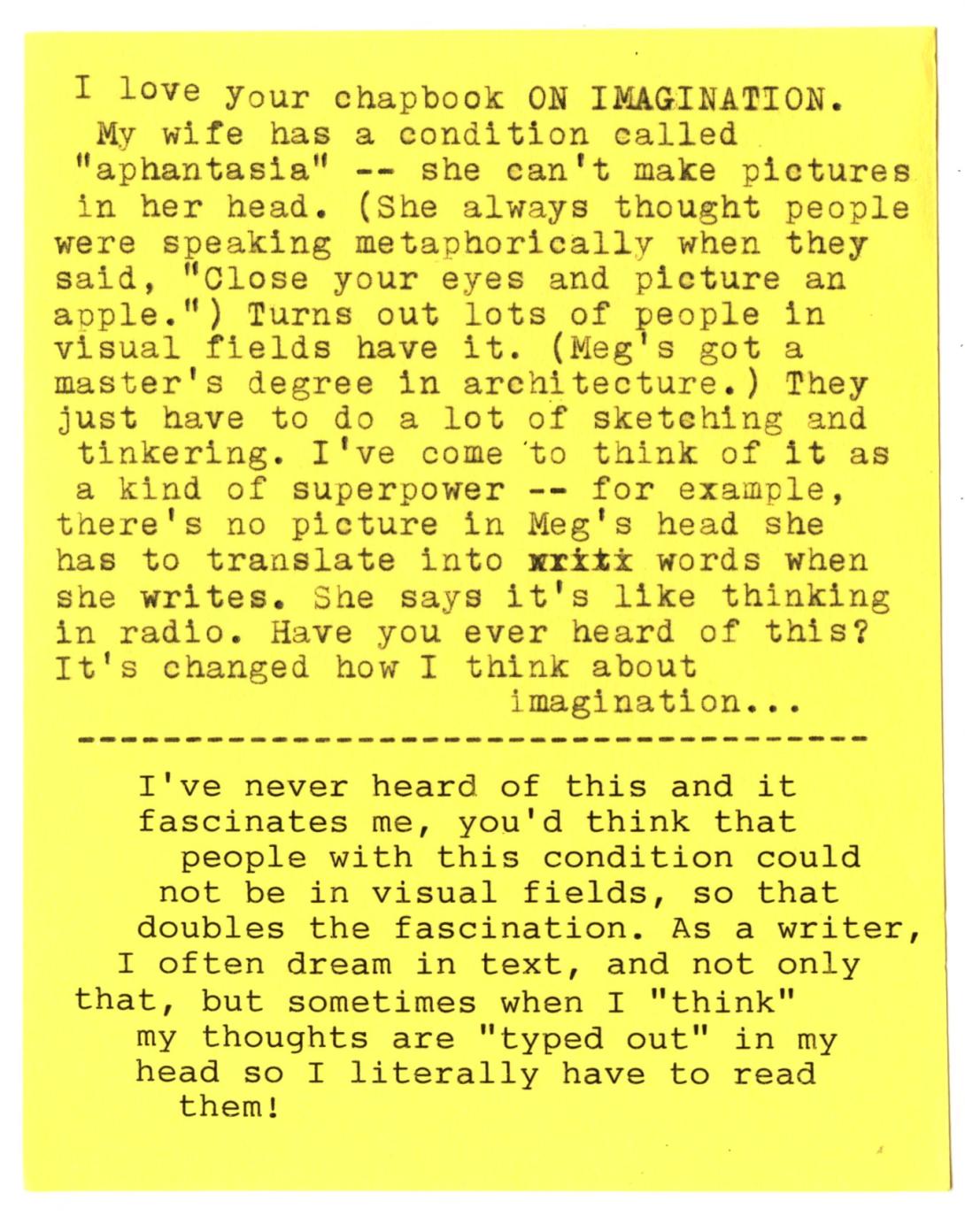

I love Austin Kleon’s Typewriter Interviews (something I wish I’d invented). I especially like his interview with poet Mary Ruefle, which includes:

I don’t know where I lie on the aphantasia to hyperphantasia spectrum, but I know for a fact that I’m far to the “a” of my “hyper” partner.

(One of the favourite things I’ve ever done is setting up a “One Minute Novel” stand on the plaza at Trent University during the annual Bacchus music festival, sometime in the late 1980s (maybe it was 1989?). I had a table and chair, and a typewriter, and I wrote (very short) novels in a minute, for a nominal fee. It was such, such fun.)

From The Rage My Father Gave Me, by Molly Rosen, in New York:

First, he started screaming at no one in particular: “What the fuck?!” Then at the receptionist, a scrawny college girl with fried blonde hair: “My daughter has been waiting for two hours, two fucking hours!”

His booming voice filled the very small office. The receptionist burst into tears. The orthodontist rushed out, ripping off his rubber gloves. “What’s going on here?”

It’s a powerful piece.

See also Martha, currently streaming on Netflix, a documentary about Martha Stewart, who seems to have been similarly shaped by her father’s rage.

I am

I am