From The Rage My Father Gave Me, by Molly Rosen, in New York:

First, he started screaming at no one in particular: “What the fuck?!” Then at the receptionist, a scrawny college girl with fried blonde hair: “My daughter has been waiting for two hours, two fucking hours!”

His booming voice filled the very small office. The receptionist burst into tears. The orthodontist rushed out, ripping off his rubber gloves. “What’s going on here?”

It’s a powerful piece.

See also Martha, currently streaming on Netflix, a documentary about Martha Stewart, who seems to have been similarly shaped by her father’s rage.

Adam Mastroianni’s post So you wanna de-bog yourself is a tour de force of life-unstucking reflection. Like:

Waiting for jackpot

Sometimes when I’m stuck, someone will be like, “Why don’t you do [reasonable option]?” and I’ll go, “Hold on there, buddy! Don’t you see this option has downsides? Find me one with only upsides, and then we’ll talk!”

I’m waiting for jackpot, refusing to do anything until an option arises that dominates all other options on all dimensions. Strangely, this never seems to happen.

Often, I’m waiting for the biggest jackpot of all: the spontaneous remission of all my problems without any effort required on my part. Someone suggests a way out of my predicament and I go, “Hmm, I dunno, do you have any solutions that involve me doing everything 100% exactly like I’m doing it right now, and getting better outcomes?”

Patrick Rhone posted a lovely recollection on the occasion of his 20th anniversary. In part:

But, truth be told, I ended up spending most of the time outside of the play talking to Bethany. She’s just the sort of interesting person with fascinating stories that you never really tire of talking to. Incredibly well read and travelled. The smartest one in the room without being annoying about it. Just when you think you’ve encountered a subject she knows nothing about, she still finds something smart and interesting to say about it.

In the spring of 2020, when I emerged solely responsible for maintenance of the estate, I asked Gary Schneider, from The Macphail Woods Ecological Forestry Project, to come and help me get the lay of the land (among many other interesting activities, Macphail Woods offers landscaping consulting).

One of the things Gary recommended was pruning the apple, cherry, and plum trees that make up a small orchard in the back yard.

I immediately proceeded to not do that.

This summer, Lisa’s uncle Brian, an architect and polymath, made a visit to the back yard to survey our sagging carriage house.

After we’d discussed its possible futures, Brian recommended we prune the apple, cherry, and plum trees that make up a small orchard in the back yard.

I immediately proceeded to not do that.

But…

Today I did.

(Photo edited to remove a shadow in the lower left, using Apple’s Photos app’s “Clean Up” feature).

The provincial government has launched a campaign, You Matter, to raise the profile of thinking about mental health in the public service workplace.

The video released to launch the campaign features a variety of public servants, followed by Premier Dennis King, and I especially appreciated his words:

I think the first thing I would tell anyone is what I tell myself: it’s okay. You aren’t broken. There’s nothing wrong with you that can’t be helped, if you recognize what’s going on, and you talk to people, and you try your best to address it.

I particularly appreciate the Premier speaking in the first person, rooting his words in his own experience. Far too often we think of mental health is being something that only other people need to be concerned with.

Next week is Transgender Awareness Week:

Transgender Awareness Week is a week when transgender people and their allies take action to bring attention to the trans community by educating the public about who transgender people are, sharing stories and experiences, and advancing advocacy around issues of prejudice, discrimination, and violence that affect the transgender community.

With anti-trans discrimination and violence such virulent aspect of the US election, this year’s marking is more important than ever.

Not Losing You is a “national PSA/micro-movie supporting trans and LGBTQ youth amid relentless anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ legislation” from filmmaker James Lantz:

Parents can play such an important role in supporting their trans kids. As the father of a trans woman, I’m viscerally aware of the prejudices, fears, and assumptions I carry inside myself, and the importance of confronting them.

I saw myself in the movie.

The single most helpful support for me as a parent supporting Olivia has been Transforming Family, a California-based support organization. Every month I facilitate a Zoom call for the parents and caregivers of autistic trans children; the people I’ve met there, the solidarity we’ve cultivated, the support they’ve offered, has been transformative.

During this important week, I encourage you to support the work of Transforming Family and similar organizations; their work is vital.

Frank reminds us that yesterday was Aaron Swartz Day.

Aaron left a comment on one of my posts here, 20 years ago, which made it feel like we were part of the same little corner of the Internet. While we never met, I felt him a kindred spirit, a much more prolific and accomplished practitioner of the same underlying digital sensibilities.

Here are some of Aaron’s own words, from his 2012 blog post Lean into the pain:

When you first begin to exercise, it’s somewhat painful. Not wildly painful, like touching a hot stove, but enough that if your only goal was to avoid pain, you certainly would stop doing it. But if you keep exercising… well, it just keeps getting more painful. When you’re done, if you’ve really pushed yourself, you often feel exhausted and sore. And the next morning it’s even worse.

If that was all that happened, you’d probably never do it. It’s not that much fun being sore. Yet we do it anyway — because we know that, in the long run, the pain will make us stronger. Next time we’ll be able to run harder and lift more before the pain starts.

And knowing this makes all the difference. Indeed, we come to see the pain as a sort of pleasure — it feels good to really push yourself, to fight through the pain and make yourself stronger. Feel the burn! It’s fun to wake up sore the next morning, because you know that’s just a sign that you’re getting stronger.

Few people realize it, but psychological pain works the same way. Most people treat psychological pain like the hot stove — if starting to think about something scares them or stresses them out, they quickly stop thinking about it and change the subject.

The problem is that the topics that are most painful also tend to be the topics that are most important for us: they’re the projects we most want to do, the relationships we care most about, the decisions that have the biggest consequences for our future, the most dangerous risks that we run. We’re scared of them because we know the stakes are so high. But if we never think about them, then we can never do anything about them.

Aaron was 26 years old when he wrote that, the year before he died. He would have turned 38 yesterday. What a loss for us all it is to have missed what he might have become in those lost years.

My Golding Jobber № 8 letterpress came to me modified by it’s previous owners, Bill and Gertie Campbell, so that a small motor drives its flywheel. In the original, the press would have been driven by a belt, or by a foot treadle; the update to an electric motor is a boon to productivity and ease of use.

Here’s what the motor looks like:

I have something of a symbiotic relationship with the motor: it turns at 1725 RPM (you can see this on the nameplate on top of the motor), and that causes the press, via the drive belt connected to the flywheel (via a bicycle wheel riveted to it) to move at a constant rate. Over the almost 15 years I’ve been running the press, the cadence of the press has been matched by the cadence of my dance with it. It’s the closest to a person-machine relationship as I’ve ever had.

To spring the press to life has always involved flipping on a light switch on the front of the press, to turn on the motor, and then giving the flywheel a nudge forward; from that point things are on their own, and the press does its half of the dance. This fall, though, this step started to falter, and the flywheel started to need a full-fledge heave-on to start rotating.

After lubricating and greasing all the parts of the press that might be at fault, I rationed that fault might lie with the motor, and that it might need a a tune-up, and so I took it out to Chandler Motor Repair, near the airport.

The motor turned out to be an object of interest, made back in the day when motors were motors. “If you were to buy a motor like this today, it would cost you $1000,” they said.

Some facts about the motor:

- It was made by the Leland Electric company of Guelph, Ontario.

- It’s a 1/4 horsepower motor, making it a fractional horsepower motor as regards regulations.

- It’s a 4.2 amp motor, which Chandlers found interesting: apparently a contemporary motor would be about half that.

Chandlers are getting back to me later in the week with an estimate for what it will take to make the motor like new again.

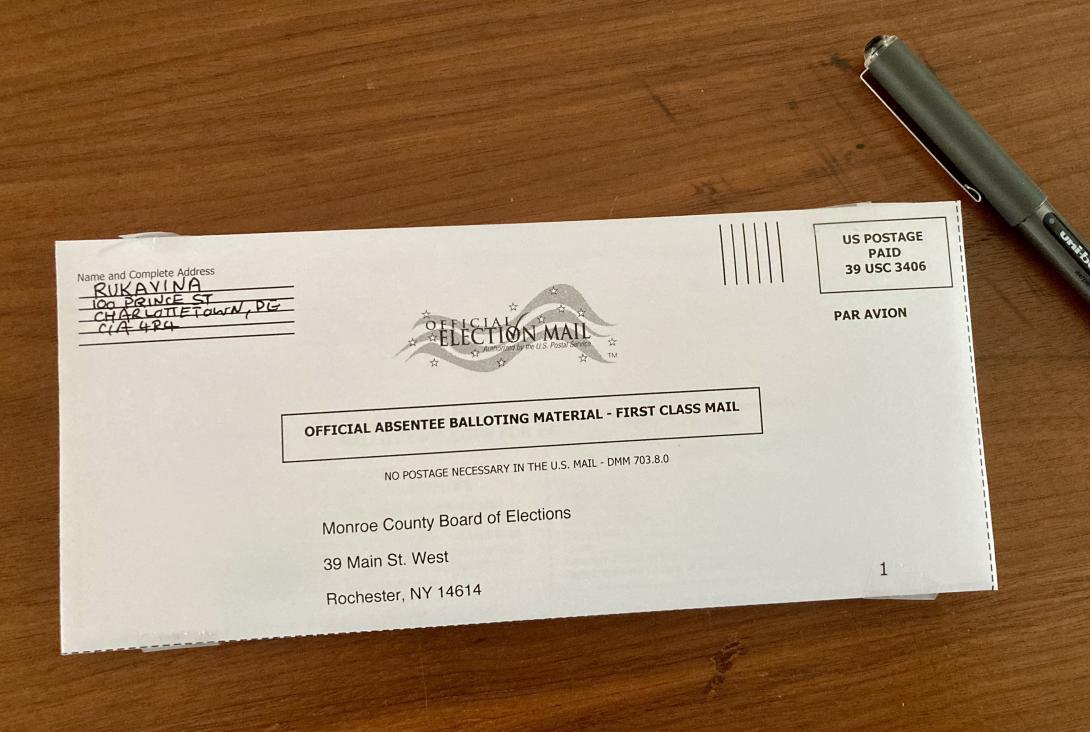

I voted absentee in the U.S. federal and state elections back in September, casting my vote for Kamala Harris.

Given the quirks of U.S. election regulations, I vote at the address where I lived with my parents, as a newborn, in 1966: 863 Post Avenue, Rochester, NY, I house we left 3 months after I was born.

I’ve been a digital hobbyist for almost 50 years, from my days fooling around with a TRS-80 Model One (on which I coded a video game, in BASIC, called “Galactic Warrior,” and then parlayed my skills into my first coding job) through to my experiments with everything from energy data to ship positions.

Along the way, I’ve accumulated a collection of websites that serve various roles. As I age, as these websites age, and as I recentre my life on analog over digital, their maintenance becomes less a “things I do while procrastinating” and more “annoying obligation.”

So I’m in the midst of a downsizing project, seeking to strip out what’s not needed, find a new home for things that are best housed elsewhere, and to preserve things that deserve preserving.

Here’s what I’ve achieved so far (I’ll update this list as I make progress).

Migrated

- WhatsMyLot.com, a single-page website that lets you find out what lot you’re in on Prince Edward Island, from you phone’s location, got migrated to a new server, and will live on. I created it in 2014 as an unofficial side project to the Samuel Holland map repatriation festivities.

- CaminoFrances.info, a single-page companion website to Bryson Guptill’s book about walking the Camino, is similarly on a new server, and will live on.

- TheIslandWalk.info, a similar single-page site showing the route of The Island Walk, has a new server too. I’ve been updating it regularly, with Bryson’s help, and the underlying data is available on Github.

- I migrated the Crafting {:} a Life website, which supported our 2019 unconference of the same name, from a Drupal site to a static HTML site, for posterity.

- CatherineHennessey.com is, I expect, one of the oldest handcrafted PHP sites you’ll come across. Catherine wrote a blog there from 2000 to 2003. It has a new server too.

- QueenSquarePress.ca and Reinvented.net, my “corporate” websites, didn’t really need dedicated sites of their own, so they now simply redirect to pages here.

- My personal wiki.ruk.ca site, which I created after I came home from Reboot for the first time in 2005, was running a very old “you can’t really upgrade easily” version of the same MediaWiki software that runs Wikipedia. As I stopped updating it a long time ago, I simply wrapped an HTML wrapper around the Internet Archive’s latest snapshot.

- HaroldStephens.net was a Drupal 5 site (!) long past its natural lifespan that I created many years ago for my late friend the adventurer and author Harold Stephens. The DNS still points my way, but I don’t control it any longer. The site will retire when my legacy server retires; after that, the Internet Archive Snapshot will preserve it.

- opencorporations.org and it’s redirected companion closedcorporations.org, held snapshot of PEI corporate registrations from 2008. I’ve shut down the public search site, but exported the raw data should others find it useful for historical purposes.

In Progress

- A collection of energy-related tools and archives — consuming.ca, pei.consuming.ca, energy.reinvented.net — remain in place. They remain valuable tools, and I would, ideally, find new homes for them, where they can be maintained permanently.

- Sites for a couple of pro bono clients — PEILegion.com, RoyJohnstone.com — maintained still in Drupal 7, need new homes and/or migrations to Drupal 10.

I expect I’m not alone, being among the first generation of Internet citizens, now in our 50s and 60s, looking at digital things through this lens.

I am

I am