Three years ago I set out to answer what I thought was a simple question: how much do I cost the health care system? I sent a Freedom of Information request to Health PEI, the public service body that manages the health system in Prince Edward Island, and what ensued was an almost-three-year back and forth – detailed in part here – between Health PEI, the Information and Privacy Commissioner and me that, as time wore on, achieved a level of absurdity that surprised me given the simple question I was asking.

My most recent communication from the Information and Privacy Commissioner on the adjuication of my appeal of Health PEI’s decision not to release cost information to me was a letter I received on January 16, 2014 informing me that the expected decision date on my case was being pushed forward to September 19, 2014 (from the originally-extended-to February 13, 2014).

Until today.

When I received an unexpected communication from Health PEI’s Privacy and Information Access Coordinator telling me that they had reconsidered and asking me to confirm my email address. A few minutes later I received an Excel file with the details of almost every medical procedure I had from 1996 (when their data starts) to June 2011, along with the name of the doctor, the location of the procedure and how much was paid to the doctor. It’s almost every medical procedure because, as Health PEI had informed me earlier, if “the service was provided by a non fee-for-service physician or was provided through a hospital (e.g. emergency department or day surgery) there are no individual payments.”

There are 58 procedures in total, ranging from “ALLERGIC RHINITIS” to “X-RAY ABNORMAL,” performed by 22 individual doctors. In total $1901.88 was paid out to doctors. While the amounts paid to physicians don’t reflect the total cost of my health care, it’s useful information nonetheless. Here, for example, are 10 items related to a the diagnosis and eventual removal of my gallbladder – an epic journey I related here – in the winter and spring of 2003:

| Doctor | Location | Date | Procedure | Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAMPION PAULINE | OFFICE | January 8, 2003 | ABDOMINAL PAIN, COLIC | 22.94 |

| CHAMPION PAULINE | OFFICE | February 19, 2003 | ABDOMINAL PAIN, COLIC | 22.94 |

| CAMPBELL CLARENCE M | QEH | February 25, 2003 | X-RAY ABNORMAL | 38.60 |

| FLEMING BARRY D A | OFFICE | February 28, 2003 | ABDOMINAL PAIN, COLIC | 63.15 |

| GILLIS LISA A | OFFICE | March 17, 2003 | CHOLELITHIASIS | 22.94 |

| FLEMING BARRY D A | OFFICE | March 24, 2003 | ABDOMINAL PAIN, COLIC | 22.61 |

| FLEMING BARRY D A | QEH | April 8, 2003 | CHOLELITHIASIS NOS | 432.55 |

| KENNEDY RALPH DOUGLAS | QEH | April 8, 2003 | CHOLELITHIASIS NOS | 108.14 |

| FARMER STEPHEN R | QEH | April 8, 2003 | OTH SPEC PROB INFLUENC HEALTH | 145.50 |

| FLEMING BARRY D A | QEH | April 8, 2003 | DAY SURGERY - HOSPITAL PAYMENT | NIL |

The total paid to the six physicians for my gallbladder issue was $879.37, and that table is a good blow-by-blow of how it was diagnosed: two visits to Dr. Champion, my family doctor at the time, a referral for an X-ray at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital followed by an office visit with Dr. Fleming, the surgeon who would eventually remove my gallbladder and then the operation itself on April 8, 2003 (“Cholelithiasis” is “the presence of gallstones”).

There are a host of other costs involved with taking out my gallbladder – nurses, machinery, heat, light, etc. It would be interesting to know what slice of the QEH budget my gallbladder removal was responsible for, but that figure seems impossible to determine, so the $879.37 will have to stand in.

Using pivot tables in OpenOffice allows me to do all sorts of analysis on my medical history: which doctors have I seen the most, what medical complaints do I seek assistance with the most, how often do I see a doctor. It’s an insight into my health care that I really value.

It really is absurd that it took almost 3 years to provide me with this information; indeed, perhaps my next request should be an accounting of the time and cost for Health PEI and the Information and Privacy Commissioner to take so long to say no before they said yes.

I’m a big believer in public health care; I consider it one of the distinguishing benefits of being Canadian. But I don’t think that not having to pay out of pocket for our health care necessarily means we all shouldn’t know how much our health care is costing the health system, if only because understanding more about the nitty-gritty costs of health care makes us more responsibile citizens when it comes to electing our politicians to make large-scale decisions about health spending.

If you would like to request the same breakdown for your health care, fill out a Request to Access Information application form (you can see how I filled mine out here) and send it to:

Privacy and Information Access Co-ordinator

P.O. Box 2000, 16 Garfield Street

Charlottetown PE C1A 7N8

Tel: (902) 368-4942

I presume that if you asked what I asked for you should receive your information quickly and without having to wait 3 years.

I first got to know Karin as a customer of her food stall at the Charlottetown Farmer’s Market. From the time Oliver was a year old, every Saturday morning, after having our smoked salmon bagel, we would have our second course from Karin’s ever-changing selection of healthy food. And she made a mean iced tea to boot – also every-changing, and unsweetened the way I like it. Karin was unfailingly kind to both of us, especially to Oliver: she was always tucking a Hallowe’en fridge magnet, or some such thing, into his pocket. Visiting her stall was one of the highlights of our week.

Gradually, Saturday by Saturday, I got to know Karin a little more. After learning of my trips to southern Sweden, she would lend me Wallander-series books, knowing that I knew the terrain. She would always tell us tales of her travels, or of her family, during those few minutes while we were waiting for something to cook or warm or cool.

After she received a diagnosis of terminal cancer in 2008, Karin asked me if I could help set her up with a blog so that she could write about her experiences, and the result was Mastering the Art of Living while Dying. There are only 34 posts there, covering the period from the spring of 2010 to the summer of 2012. But in those posts you’ll learn a lot about Karin, and a lot about her take on, well, living while dying. Two years ago she wrote Would She Just Die Already?, one of my favourite of her posts because it captures the humour and joy that Karin brought to everything she did:

It has been more than 3 years since the doctors have told me that there is no story. No cure, no treatment, Nothing, Nada!. That was pretty harsh news. So my friends and I gathered around and comforted one another and decided we should all live our days like they are our last days. So here I am three years later, doing just that. I’m living my life like it is my last days. Now my friends are like…o.k. it’s been three years, would she just die already. I’m no longer on their “pitiful friends” list.

This Karin person is having way too much fun living her last days. I’m a pain in the butt! Sure we need to live our lives like it our last but you can only do that so long. Especially if you have a family to raise and bills to pay. But here is Karin, having lots of fun, going on trips while my friends are trying to pay the mortgage and raise their children. Most of my friends have forgotten that I have cancer. They have moved on to their sicker and needier friends.

But seriously, I am so blessed to still be here after 3 years of getting a terrible diagnosis and I am enjoying my life. Every day of it. If I die tomorrow, I would be high-fiving someone and thanking them for giving me these wonderful and precious days. And… just for the record, it’s kind of cool that my friends and I have forgotten I’m dying. Better run and pack my suitcase for my next adventure! Blessings!

Somehow, amidst treatment and recovery and despite myriad challenges of world-travel-health-insurance – the kind of thing you never think about until you need it – Karin and her intrepid partner Mike saw a lot of the world in the last few years. She published a cook book. She met a grandson. She did live while she was dying. She would probably say that she didn’t master it; but she sure gave it a good chance.

Karin died this weekend. I hadn’t seen her in a few months, and she had been not dying for so long that it came right out of the blue for me. She was a good person, someone who we were all the better for knowing, and she will be missed.

Dzintars Cers has two albums of delightful Latvian-infused progressive rock. This is amazing. That is all. (Go and buy them now: only $7 each).

(The “voice of strength” tagline is from Dzintars’s website, also awesome).

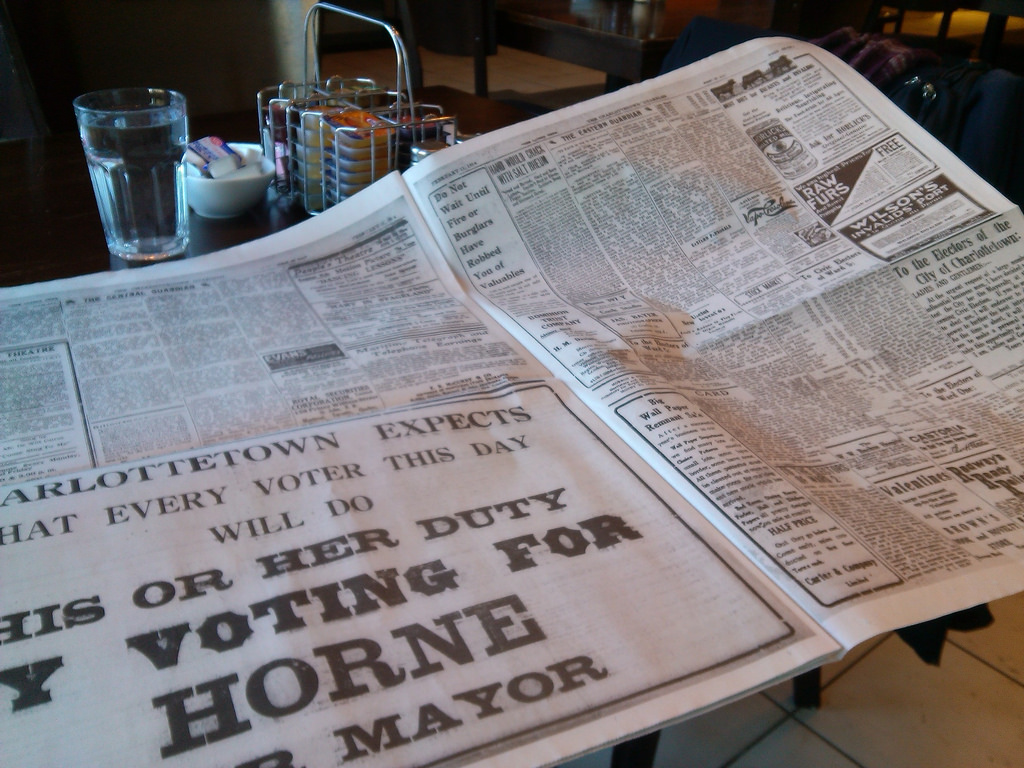

As part of the launch of the IslandNewspapers.ca project today, we arranged to have Transcontinental Printing in Borden – the branch of TC that prints The Guardian and the Journal-Pioneer – produce a facsimile of the February 11, 1914 newspaper, printed first 100 years ago today.

The process turned out to be rather simple: I grabbed high-resolution TIFF files from the IslandNewspapers.ca page for this date, uploaded them to Dropbox where the composing room in Borden could grab them, they sent along a proof press to the Guardian office in Charlottetown the next day, we agreed on a price and 500 copies showed up in Charlottetown this morning. Magic.

I’m very, very happy with the result: they were able to recreate the historical wide-broadsheet size of the 1914 paper, and while the source material – scans of microfilm of originals – wasn’t perfect, the paper is eminently readable and, for most intents and purposes, just like reading The Guardian 100 years ago.

Knowing we’d have more than enough copies to meet the demand at our launch event, I spent the late morning walking all over downtown Charlottetown delivering copies: the Coles Building, City Hall, coffee shops, the public library. My favourite stop was Hyndman & Company on Queen Street, my own car insurance broker and a company that was already established – and a regular Guardian advertiser – by 1914.

When I was done making my rounds, I sat down for an early lunch at Casa Mia Café and enjoyed the experience of reading the paper, 100 years on, as if it was today.

You can pick up a copy of the 1914 Guardian at the The Guild box office, at Confederation Centre Public Library or at ROW142 coffee on Richmond Street while supplies last.

I met Mark Leggott at the Access conference in St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1994. We kept in touch over the ensuing years, and renewed our acquaintance when Mark moved to Prince Edward Island in 2006 to become Chief Librarian, University of PEI. In the years since we had the occasional lunch or coffee and would often chat about the projects that Robertson Library was undertaking and how I might become involved with them in some capacity.

At our first such meeting I mentioned that, on my list of dream projects, was a digital archive of Prince Edward Island’s newspaper of record, The Guardian: as someone occasionally interested in plumbing the depths of the Island’s history, I knew firsthand how cumbersome using the microfilm version of the paper’s archive is, but also knew, from those times when I braved it, how rich a resource the historic Guardian is.

Mark is nothing if not a digital-projects-generating-dynamo, and he took this idea and ran with it, rallying resources, funding, expertise – and the cooperation of The Guardian itself – and it is with much joy that I can invite you all, all these years later, to attend the formal unveiling of the digitized Guardian, covering issues from 1890 to 1957, tomorrow, February 11, 2014 at 2:00 p.m. at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown.

Mark is nothing if not a digital-projects-generating-dynamo, and he took this idea and ran with it, rallying resources, funding, expertise – and the cooperation of The Guardian itself – and it is with much joy that I can invite you all, all these years later, to attend the formal unveiling of the digitized Guardian, covering issues from 1890 to 1957, tomorrow, February 11, 2014 at 2:00 p.m. at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown.

As a special incentive, we’ll be distributing paper copies of the February 11, 1914 newspaper, being printed in Borden as we speak. It was municipal election day 100 years ago tomorrow, so the day’s paper is full of election coverage.

The archive is online at IslandNewspapers.ca right now, and I encourage you to take a look, plumb its depths, and offer the project team feedback. Their work to date, from the physical process of digitizing to the digital process of archiving, OCRing the text, and building a web front end, is impressive, and they each deserve a hearty congratulations at tomorrow’s opening.

Of course, as Hacker in Residence, I had to dip my own toes in the water, and so in addition to the IslandNewspapers.ca site itself, I’ve leveraged the openness of the project to build some side-projects around the 100-years-ago-today newspaper:

- A Twitter account, @peinewspapers that tweets the front cover from 100 years previous.

- A Tumblr blog, at http://peinewspapers.tumblr.com/ that does the same thing.

- A Facebook page, at https://www.facebook.com/dailynewspaperpei where, in the same vein, you’ll always find the day’s paper from 100 years ago.

I encourage you to befriend / follow / like any or all of the above and, even more so, to become a reader of the daily paper 100 years on: I’ve been reading The Guardian from 1914 every day this year, and the context the emerges watching stories evolve from day to day provides a new view into history. This will become even more interesting as 1914 marches on, with the 50th anniversary of the Confederation Conference and the start of World War One still to come.

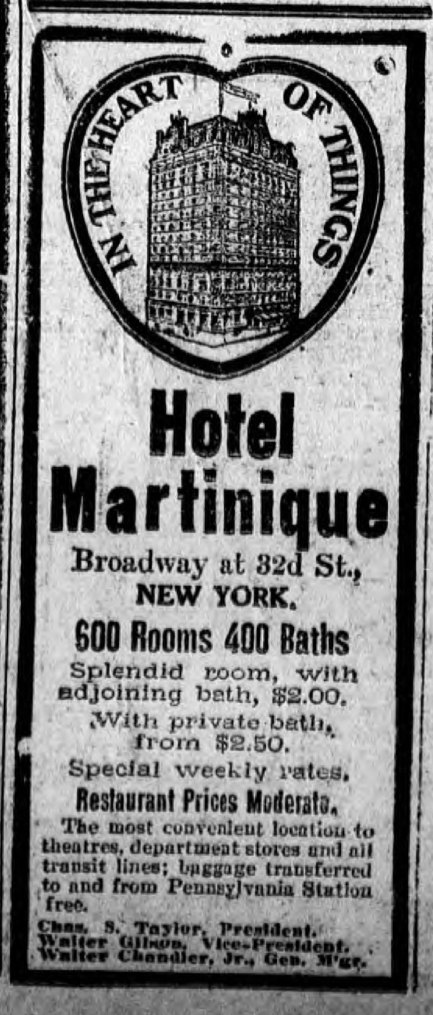

From The Charlottetown Guardian, February 10, 1914, an advertisement for the Hotel Martinique in New York City, at the corner of 32nd and Broadway:

From Google Streetview, the Hotel Martinique today, now the Radisson Martinique:

In the intervening 100 years, the Martinique was a “notorious welfare hotel.” Today the hotel lists it’s lowest average daily rate at $175.00.

Yesterday my brother Steve, initially a Twitter-skeptic and now one of the most prolific twitterers I know, piled on to the #CBCBands hash tag with gusto ( “ ‘The National’ Research Council Official Time Signal,” “T-Rex Murphy,” “Radio Radio Noon,” etc.). I’m biased, but I’d say he led the pack.

At the end of which brother Johnny dropped in with “I thought it was too much until Dzintar Cers Mix-a-Lot.”

Which answered a long-burning question for me: how do you spell Dzintar Cers (one of the CBC’s best newsreaders and someone I’ve woken up to on the clock radio hundreds of times).

Which, in that rabbit-holey Internet way, eventually led me to this description, from Toronto’s Eye Weekly from 1998, of a Dzintar Cers side-project called Dzena’s Initiation:

This is what happens when you let one CBC sportscaster (Dzintar Cers) and one nutty freelance performance artist (Nina Hilger) loose in a digital portastudio with a computer music-generating program. He plays (in a prog-rock meets techno kind of way) and she rants. This goes on for over two hours. Occasionally Cers’ brother Aldis provides some wild acid-rock guitar. Song titles include “Nuclear Marionette’s Dinner Party,” “Mother Dominatrix” (the S&M crossover hit single) and, my fave, “India Nomo,” featuring thoughtful lyrics sung by Cers in his native Latvian tongue.

If the universe is just, someone will find a copy of this and send it to me. Right now.

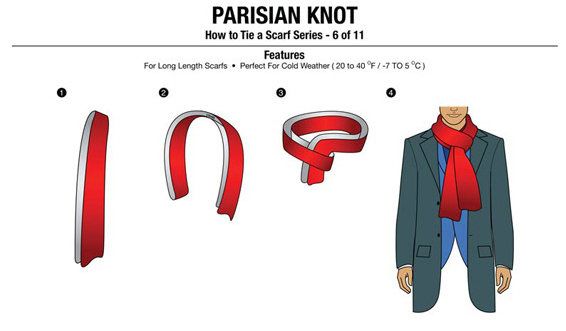

I’ve been tying knots the wrong way, I have learned.

First, I’ve been knotting my shoes the wrong way, as I learned from this TED video. Six months ago I switched to the new system espoused there, and went from having my shoelaces becoming undone two or three times a day to having my shoelaces never becoming undone. I took about 2 weeks until my muscle memory learned the new method, but it’s now second nature.

Second, I’d been knotting my scarf the wrong way. Truth be told, I wasn’t knotting my scarf at all, simply draping it around my neck and holding it on with my coat. But then, two days ago, I carefully watched as my friend Shelley did what I’ve come to learn is called the “Parisian Knot,” a simple technique that is well-illustrated here:

I’ve only been Parisian for 12 hours now, but the change is palpable: I’ve moved from “vaguely warmed neck” to “warmly swaddled neck.

It’s Data Privacy Day today, and I started the day off by reading Five Potential Privacy Pitfalls for Developers from Mozilla. One these pitfalls Mozilla describes as “More isn’t always better,” described, in part like this:

The key is to collect only what you need. When you are in the planning stages for your app, document the data collection, usage and flows. You should be able to justify each piece of personal information and describe how it will be used. If you plan to collect personal information for future or extra features beyond core functions, always give users the ability to opt-out.

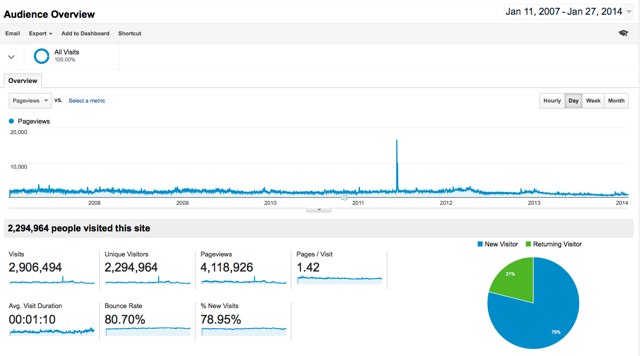

For the past 7 years I’ve been collecting Google Analytics data on every visit to this blog. This is typical behaviour for websites – even the Mozilla blog post above is collecting Google Analytics data – and is something that allows website owners insight into how their site is being used and by whom.

Google Analytics does this all anonymously: it tells me how many people from Virginia visited my blog yesterday, but not who they are.

But even though that’s true, as I related late last year, it’s not as though the collection of this information comes completely without a price for my readers, because Google aggregates the data I allow it to collect here with data from millions of other websites to form a sort of “behavioural fingerprint” for every reader, with a visit to this space being one small data point that helps to flesh out, to Google and its customers, if not who you are, at least how you are.

Sometimes this is a reasonable exchange – as Mozilla writes, “User data is undeniably valuable and collecting it isn’t inherently wrong, especially with consent.” – and when I am wearing my commercial hat I can attest that the data Google Analytics provides allows me to help build more effective (for both author and reader) websites.

But here on ruk.ca, well, not so much. I’ve glanced at Google Analytics data every few months out of interest, learning what posts here are popular, where readers are coming from, how long readers typically spend reading.

But if the “the key is to collect only what you need,” then it’s hard to justify collecting even anonymous data about you readers, especially if, in doing so, I’m helping Google digitally fingerprint you.

So, starting today at 9:00 a.m. Atlantic time, I have removed Google Analytics tracking from this site. The line graph will flatline, and I will no longer know anything about who you are, how many you are, and what you’re reading.

I’ve always maintained that I write this blog mostly for myself, as a way of processing what happens in my life and what I’m thinking about; it’s not a diary, and its publicness has always been important to the rigour of the place, but I’ve never written for you.

And if I’m not writing for you, then I don’t really need to know that you’re a 46 year old woman from Idaho who likes TV and is in the market for a new motorcycle.

Enjoy your newfound anonymity.

I am

I am