I remain unsure exactly how to describe House Industries (which I think is kind of the point of House Industries), but I enjoyed the Cool Tools interview with co-founder Rich Roat, and especially his recommendation of French Paper Co.:

“In the old days of graphic design, premium printing paper was a B to B thing and you had to buy the stuff through a print shop who had to buy it through their local distributor. When Andy and I first started House Industries, we were in Delaware and no Delaware distributors carried French, we posed as a print shop so we could order their paper direct from a Baltimore distributor and have it shipped to another printer, sort of like the CIA set up a shell corporation to buy titanium that they needed to build the SR71 blackbird from the Russians during the cold war. We were friends with fourth-generation owner Jerry French, but, at the time, it was verboten for paper mills to sell direct to designers. Still, Jerry would see that some “fell off a truck” every once in a while to fuel early House Industries font catalogs. Then the internet came along and fucked a bunch of shit up, but also eventually made it okay for French to sell direct to consumers. Anyway, about the paper itself: unbeatable color palette and delicious textures, mostly attributed to hero graphic designer Charles S. Anderson. Their swatch books are more valuable than a PMS chart and if you have a pernickety printer who doesn’t feel like doing a little sourcing, you just get out your credit card and order it yourself. French is also a really cool company, surviving as an independent mill in a time when most other such businesses are long gone. And they were generating their own hydroelectric power, recycling and being environmentally-friendly before those kind of things were cool, like almost 100 years ago.”

From a recent interview in Nautilus with biologist Jason Munshi-South:

Is the history of New York City inscribed in the genes of mice?

Partially, yes. We can imagine before Europeans the mice were everywhere, moving around. As Europeans developed New York City and southern Manhattan, and then agricultural areas everywhere else, the mice were probably still moving around for the most part through agricultural areas. But once you got to heavy urbanization of Manhattan about 150 years ago, and of the other boroughs about 120 years ago, in a matter of a few decades these parks were developed and became quite isolated.

We can use the genetics to date when populations became isolated. The dates are rough because we have to make some assumptions, but they do coincide with the history of urbanization in New York City. So that history is written into the genes of some of these animals.

My friend Mark pointed me to Nautilus–”a different kind of science magazine” is how it describes itself–and, based on his recommendation, I subscribed to the print and RSS.

If evolutionary rodent biology is your thing, be sure to also read Randy Dibblee’s The Beaver on Prince Edward Island: Seeking a Balance, from Island Magazine. It’s a gripping tale: beavers were extirpated here by the late 1800s, and then reintroduced in 1908. We’ve had a fractious relationship with them ever since:

Not everyone considers the beaver a benefactor. From a human perspective, the ability to create valuable wetlands can also cause destruction. Like most wildlife, beavers are perceived as prob- lems when their activities are at odds with human objectives. Their ability to block water flow, plug culverts, and flood cultivated land, plantations, high- ways, and access roads — not to mention their woodcutting acumen — puts beavers at the top of the “problem wildlife” list for North America.

The Island Fringe Festival had its launch party last night at Marc’s Lounge, and Oliver decided that he wanted, at the last minute, to respond to the open call for poets to read “found poetry.”

Fortunately the Fringe team is on the ball and digitally-engaged, so the request-to-perform reached them in time for him to make the list. And so we headed over to secure a seat around 7:30 p.m. for an 8:00 p.m. start.

Because of Prince Edward Island’s antediluvian liquor laws, Oliver was only allowed to be present until 9:00 p.m., and so there was some last minute stress surrounding whether he’d be able to go on stage before turning into a Prohibition pumpkin, but, again the Fringe team rose to the challenge and made sure he was on in the first hour.

Oliver is a master of the acrostic poem, an excellent adaptation that accommodates he’s need to express with his challenges with choices: it’s a poetic hook to hang his hat on, so to speak, and to watch him pull a poem out of the digital ether is a sight to behold.

Here’s the poem he read:

Had

IPods

Pluto

Songza

That are now Things of the Recent Past

Extinct

Revolutionized Cities

Short Vine VideosYearning for

Unoriginal Objects

Continuing to Recreate

Completed Things

In the Present

Existing Past

Since ThenMany Revolutionized Cities and Had

IPods and Pluto

Leaned

Lots

Extinct

Now Not New

IPods

Another

Last Generation That are Now Things of the Recent Past

Short Vine Videos and SongzaGrowing Generation

Everyday

New

Era

Recreate

Atari

Today

It

Only Continues to Grow

NowXenocracies

Everywhere

Really

Soon

I love the phrase “continuing to recreate completes things in the present.”

There was an intermission of sorts just before 9:00 p.m., and Oliver insisted we high-tail it for the door lest the Provincial Treasurer come and haul us out by the coat tails.

In the ragtag posse of Whole Earth-loving hacker-designer-writer-artist-futurist iconoclasts that I hang on the edges of, the 1977 book A Pattern Language, by Christopher Alexander, is tantamount to a bible; it’s referenced with the same reverence as McLuhan’s Understanding Media.

How can you not, after all, love a book that contains such aphorisms as:

It is a mark of success in a park, public lobby or a porch, when people can come there and fall asleep.

and:

If the right rooms are facing south, a house is bright and sunny and cheerful; if the wrong rooms are facing south, the house is dark and gloomy.

What’s not as well known as the astute aphorisms is that A Pattern Language is one of a trilogy that includes The Timeless Way of Building and The Oregon Experiment.

I’ve been reading that latter book over the last few weeks; it is a fascinating book that both puts forward a new approach for community planning and is also a master plan itself, for the University of Oregon.

While the books ruminations on space and landscape and other more concrete issues of planning are interesting, it is its focus on participation that I find most compelling; the approach is one that has far greater applications:

Let us try to explain why we believe this form of participating is so important to the University.

There are essentially two reasons. First, participating is inherently good; it brings people together; involves them in their world; it creates feeling between people and the world around them, because it is a world which they have helped to make. Second, the daily users of buildings know more about their needs than anyone else; so the process of participation tends to create places which are better adapted to human functions than those created by a centrally administered planning process.

The book goes on to describe this process by which these “daily users of buildings” will design the buildings themselves, designs that will then be implemented by architects and builders.

This is not the way things are usually done: we are conditioned to expect that it works the other way, with some “centrally administered planning process” (a government department, say) designing something and then seeking “public feedback” on what it has conjured. This “consultation” has the appearances of being “participatory,” but is, in fact, the opposite.

We live, here in Prince Edward Island at least, in a sort of golden age of consultation: going back 20 years to Pat Mella’s term as Provincial Treasurer, we’ve had “pre-budget consultations” and “round tables on the land” and “red tape reviews.” They sing from the same song book: “here’s what we’re planning to do, what do you think?”

That is not participation as Alexander describes it, it’s merely a crude simulacrum of it, with none of the important qualities; one does not emerge from a pre-budget consultation with “a feeling between people and the world around them.”

We’ve spent some time, as a family, in the offices in Charlottetown from which the Social Assistance program is administered, offices that are shared with the Disability Support Program that we’re there to see.

The offices are squirreled away in an anonymous, windowless bunker in the Ellis Bros. shopping centre; the waiting room is as if in a prison, with glass partitions separating the clients and the staff, and absolutely nothing interesting to read except the proscriptive posters on the wall.

It is not a place you’d want to spend any time, no matter who you are.

What would a place like this look like if, rather than being designed by “central administrators,” it was designed by the people it is there to serve.

What would that process look like? How could it bring people together? Is it possible to transform such a space into a something that “creates feeling between people and the world around them, because it is a world which they have helped to make?”

I would like to find out.

As I get older, and realize that it is my peers and I who are running the world, I am aware that this realization presents a fork in the road.

One can seize the opportunity, leverage the experiences and connections a lifetime in the making, and seek to reshape the world as they’ve always thought it should be shaped.

Or, instead, one can take the moment to reflect on who is missing from the group, who’s left out of participation, who’s having solutions designed for them, not with them. This reflection need not extend from simple altruism: participation makes better solutions. For everyone. And so when some are left out, and when the process is unbalanced, or merely consultative, it is a practical crisis, not a spiritual one.

We are good at encouraging the former approach (it’s called “community leadership” or “entrepreneurship” or “political involvement”).

We’re dreadful at the latter one, both because it involves re-balancing power, but, more importantly, because we lack the basic skills, collectively and individually, required to allow participation to live and flourish and become the way we typically do things.

Later in the same chapter on participation, Alexander describes creative control and involvement:

These two aspects of involvement–creative control and ownership–are of course related. You cannot control a place unless to some extent you own it. And you cannot have a sense of ownership unless to some extent you can control it. Students and faculty will never feel any true sense of involvement in the university unless to some extent they own their labs and offices, and unless, to some extent, they can control the changes there to suit themselves.

Consultation engenders neither ownership nor control; participation does.

The past couple of morning I’ve had business uptown in the morning, so I’ve put my bicycle on the bus going north and then cycled back, taking advantage of geography to lessen the effort.

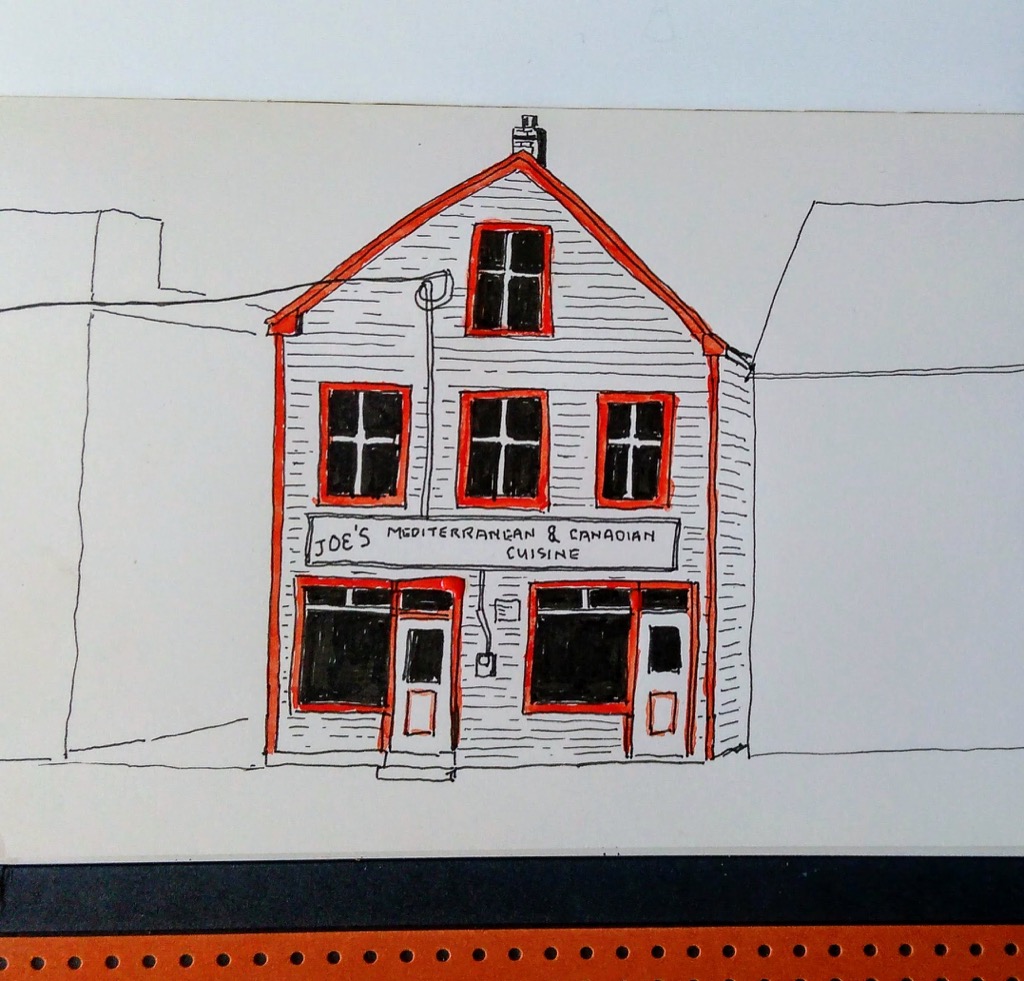

Although the ride back isn’t arduous–it’s almost all downhill–it’s nice to stop for a break near the end, so two mornings in a row I’ve stopped at David’s Tea for an iced tea before continuing. David’s has a nice counter with chairs that runs across the front, affording a view of the street out front. This morning I set out to sketch Joe’s Mediterranean & Canadian Cuisine across the street, a building that, in this incarnation, is resplendent in its orange.

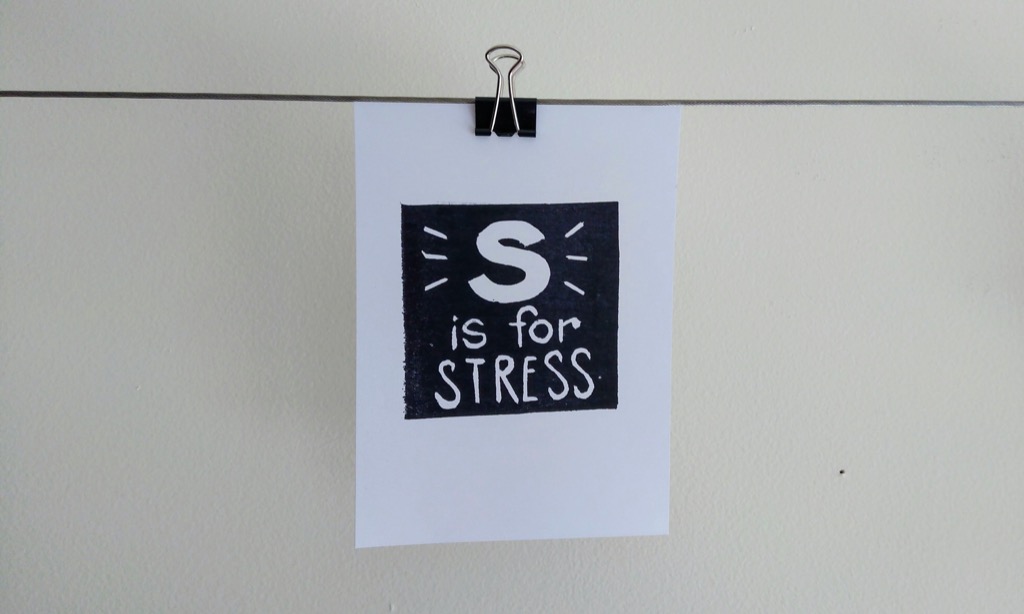

Jenni Zelin’s A is for Angst: An Alphabet of Woe, opening tonight at The Guild and running until August 13, is an art exhibition surgically designed to hit me on almost every artistic pleasure centre: typography, mixed up media, do-it-yourself activities, repetition on a theme.

It is my favourite Gallery at the Guild show of the year (at least). If you only see one show this summer here, come see this one.

Danny Gregory has a weekly “sketchbook club” video series on YouTube where he leafs through sketchbooks–his own or others’–and uses what he sees as a jumping off point for talking about sketching.

In this week’s edition he shows off his own first sketchbook, from the late 1990s; twenty minutes in there’s a comment from a live viewer, Valerie:

It looks like you already knew how to sketch at this time; I don’t know how to start.

Gregory, in responding, lays out a sort of “philosophy of sketching”:

I started this way: by carrying a sketchbook around, and recording what I saw in my life. That is how you start. Now you know.

He continues down this road, and by the time he’s done he’s described something that works well for sketching, but which is also a pretty good prescription for taking on anything new.

As someone who’s been carrying around a sketchbook in his back pocket for the last 4 months and recording what I see in my life, I can attest to this: there’s no better way to start seeing than by opening your eyes.

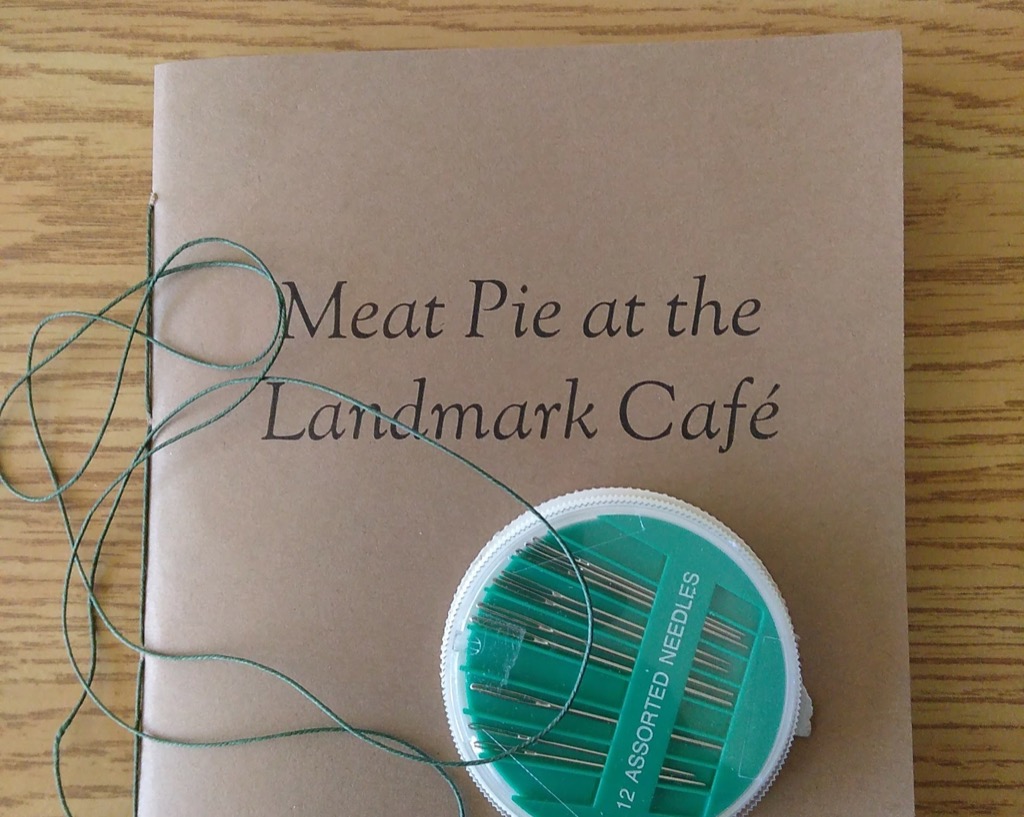

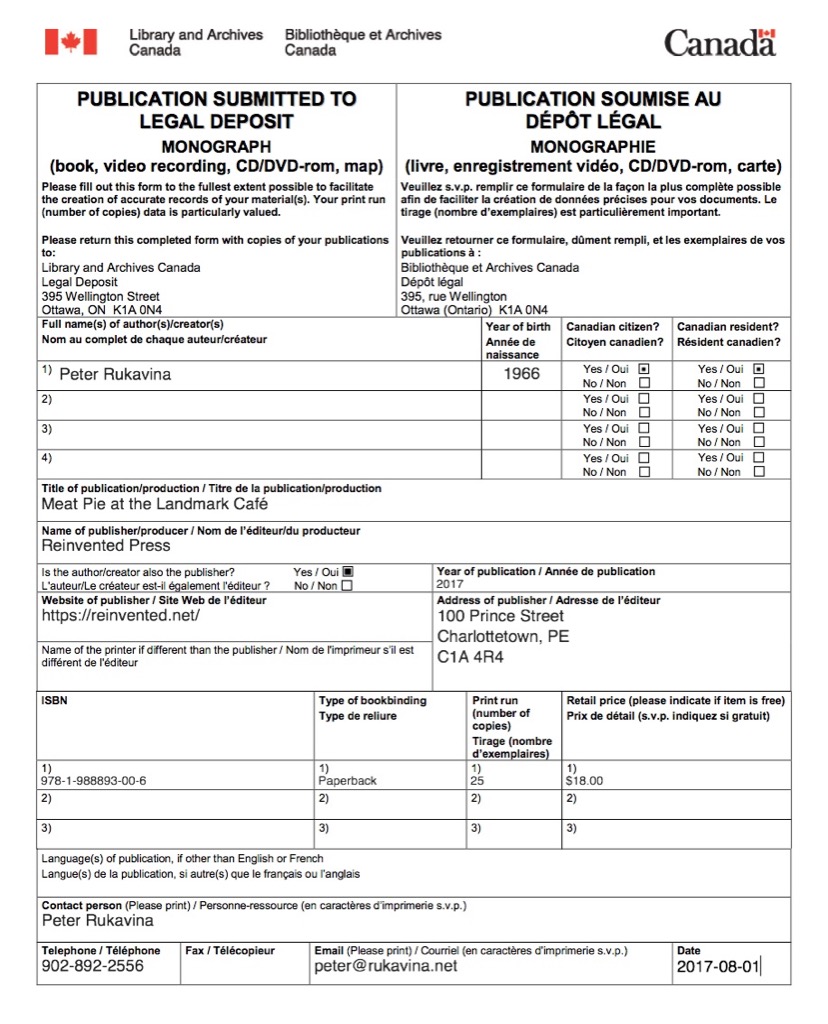

Now that Meat Pie at the Landmark Café has an ISBN, I need to send a Legal Deposit copy to the National Library:

The national library collection is assembled through legal deposit and becomes the record of the nation’s published heritage. Legal deposit applies to all publishers in Canada, and to all publications in all mediums and formats. Through legal deposit, all materials produced by Canadian publishers become part of Library and Archive Canada (LAC)’s collection and are available for public consultation and use.

Once a publication is received, a description acknowledging the contribution of the publisher is entered into LAC’s online catalogue, which can be accessed by all Canadians in the comfort of their home.

So I printed a copy specifically for this (a modest effort than it might be otherwise, as my letterpress printing skills haven’t graduated to texts of this length yet) and bound it together using the technique I learned from Jennifer Brown:

Next, I filled in a Publication Submitted to Legal Deposit (Monograph) form. I needed to set a price for the book, and so I chose $18 because that’s the price of an actual meat pie at the Landmark Café, and it seemed like the book should cost the same thing.

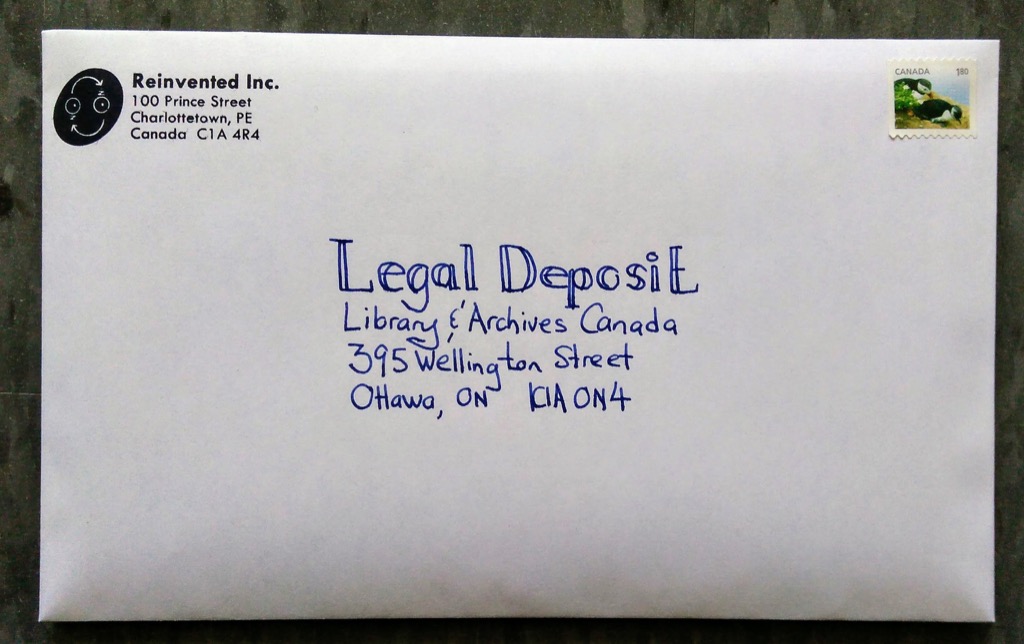

I bundled everything together in an envelope, and it will go out in the 5:00 p.m. mail, off to live its new life as part of the “nation’s published heritage.”

Two months ago I produced a little book, about a Saturday spent with Oliver, called Meat Pie at the Landmark Café.

Among other things, the writing, printing and binding gave me a taste of what it takes to manufacture books in small quantities, and I decided to follow through into the next step, and use the project to see what happens next.

First step: get an ISBN.

I’d always conflated product barcodes and ISBNs: they do, after all, look the same.

But barcodes for products require Global Trade Item Numbers (GTINs), and getting GTINs requires paying for a Prefix License.

But ISBNs are free, and easy to get via Library and Archives Canada.

So that’s what I did: registered myself up as Reinvented Press (which took about a week once I submitted the application) and then, once I was approved, registered an ISBN for my book using their web system (which was instantaneous).

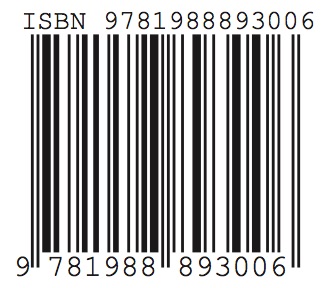

And so Meat Pie at the Landmark Café is now ISBN 978-1-988893-00-6.

I fed that ISBN into this ISBN bar code generator and, presto, I have a barcode for the back of the book too:

My next step is to print and bind up another copy of the book so that I can fulfill my obligation to provide a Legal Deposit copy.

I moved to Montreal in the fall of 1990, having managed, by way of a few months in El Paso, Texas, to develop enough momentum to achieve escape velocity from Peterborough, Ontario, where I’d lived since the fall of 1985.

My friends Jill and Colin were already there–Jill had been my roommate the year before–and I knew a few other people in the city, but mostly I was a stranger in a strange land. I was unemployed and collecting unemployment insurance, didn’t particularly have a plan, and, in the end, was much more not somewhere else than I was in Montreal.

I started out squatting with Jill and Colin in their studio on St-Laurent and, after a few weeks, found a sublet on the 31st floor of a high-rise at 2250 Rue Guy, near Maisonneuve. I spent a few months there before decamping, midwinter, for 6107 Avenue du Parc, near the north-western edge of Mile End.

My time in Montreal was not entirely without its pleasures. On Tuesday nights I took “French as a Second Language” from the Catholic School Board. I ate a lot of bagels. I spent a lot of time on the Walden Commune BBS. I had a tiny black and white television and every night I’d stay up late to watch Newhart followed by the late movie on the local CTV affiliate.

But I didn’t really have enough money, or friends, to truly enjoy living in Montreal, and the alienation of the long, snowy, cold winter combined with the alienation of being a mostly-unilingual anglophone meant that I did not feel wrapped up in the warm embrace of the city.

It’s not without irony that when I return to Montreal these days, it’s Mile End that I often find myself returning to; Oliver and I were there just last month, and it looked and felt nothing like the cold, austere place I remember it being.

By spring–arguably the nicest time of the year in Montreal–I was ready to get out, and when a job opportunity at the Peterborough Examiner presented itself, I jumped at the chance, calling up my friend Stephen for help, loading my life’s possessions into my Toyota Tercel and a rented van, and re-entering the Peterborough orbit after only 9 months away.

This adventure would have an unhappy ending if not for the fact that I happened to move into 621 George Street North to become roommates with my friends Tim, Dy and Richard; next door at 627 George Street North lived a young woman named Catherine Miller. Because Tim and Dy were out of town when I landed, it was Catherine who handed me the keys to my new place. It was the first time I laid eyes on her. We’ve now been together almost 26 years.

It’s taken me most of that time to be able to look more fondly on Montreal. Having a brother and sister-in-law there and two strapping young nephews helps, of course, but it’s mostly the passage of time that’s allowed me to experience Montreal’s many pleasures.

But there’s no getting away from the fact that, the first time around, I absolutely flunked at Montreal.

I am

I am