As someone who often walks around town with a son with service dog in tow or with a partner using a walker, I notice, a lot more than I used to, when shops and restaurants don’t have accessible power-operated doors. I asked the City of Charlottetown Planning Department about this, and the Building Inspector helpfully replied with a reference to the 2010 National Building Code, Section 3.8 Barrier Free Design:

Except as provided in Sentences (6) and (12), every door that provides a barrier-free path of travel through an entrance referred to in Article 3.8.1.2., including the interior doors of a vestibule where provided, shall be equipped with a power door operator that allows persons to activate the opening of the door from either side if the entrance serves:

a) a hotel,

b) a building of Group B, Division 2 major occupancy, or

c) a building of Group A, Group B, Division 3, Group D or E major occupancy more than 500 m2 in building area.

(See Appendix A.)

Pulling this apart, power doors are required for:

- Hotels;

- Buildings “of Group B, Division 2 major occupancy”: these are hospitals, nursing homes, and similar facilities;

- Buildings “Group A, Group B, Division 3, Group D or E major occupancy more than 500 m2 in building area”: this includes everything from cinemas to libraries to banks to shops and restaurants.

The places I’m concerned about most often fall in the third item–shops, restaurants, etc.–and the reason that the examples I cited to the Planning Department as lacking accessible doors are, it seems, exempt under the “more than 500 m2” provision.

Five hundred square meters, or 5381 square feet, is a pretty large space (our house is 2400 square feet over two floors). This means that most shops and restaurants would fall under the amount of space, and not be required to have an accessible door.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that such spaces can’t install a power door, and I encourage everyone, in their comings and goings, to encourage shops they patronize to improve accessibility in all ways, including this one.

(The City of Charlottetown is migrating from the 2010 National Building Code to the 2015 National Building Code; the Building Inspector confirmed with me that nothing has changed with regards to the 500 m2 cut-off in this regard).

Crapaud, Prince Edward Island is, as I’ve written about at some length, a round municipality.

According to the History of Crapaud, the boundary of the village was set as follows:

It was further decided that the incorporated area should include all land and water within a half mile radius of Crapaud Bridge, which spans the Westmoreland River, on the present course of Highway Route No. 9.

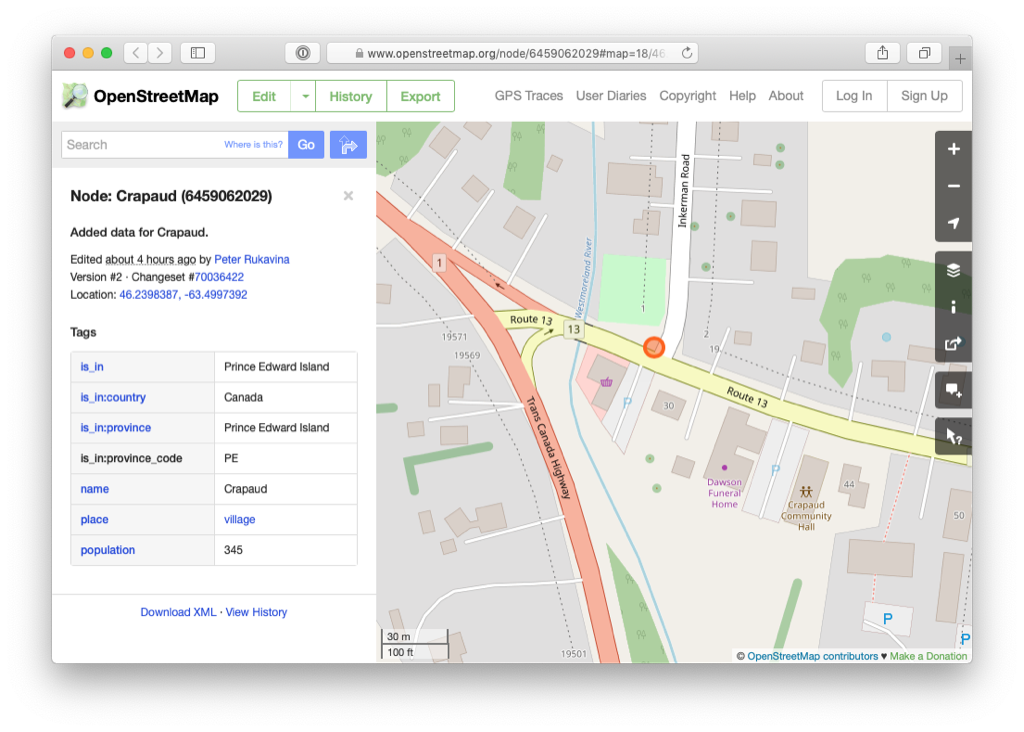

To ensure that OpenStreetMap’s representation of Crapaud aligns with this description, I moved the point marking Crapaud to 46.2398387, -63.4997392, the centroid of the circle that describes the boundary:

Eagle-eyed readers will note that this point falls about 30 meters east of “Crapaud Bridge, which spans the Westmoreland River,” which is where history describes it. It turns out that proclamation in the Royal Gazette of Crapaud’s incorporation refers only to “Crapaud Corner,” without a more specific geographic location; when digital cartographers of yore created the Crapaud municipal boundary in its contemporary digital form they thus had to take their best guess, and what you see in OpenStreetMap is the boundary they came up with.

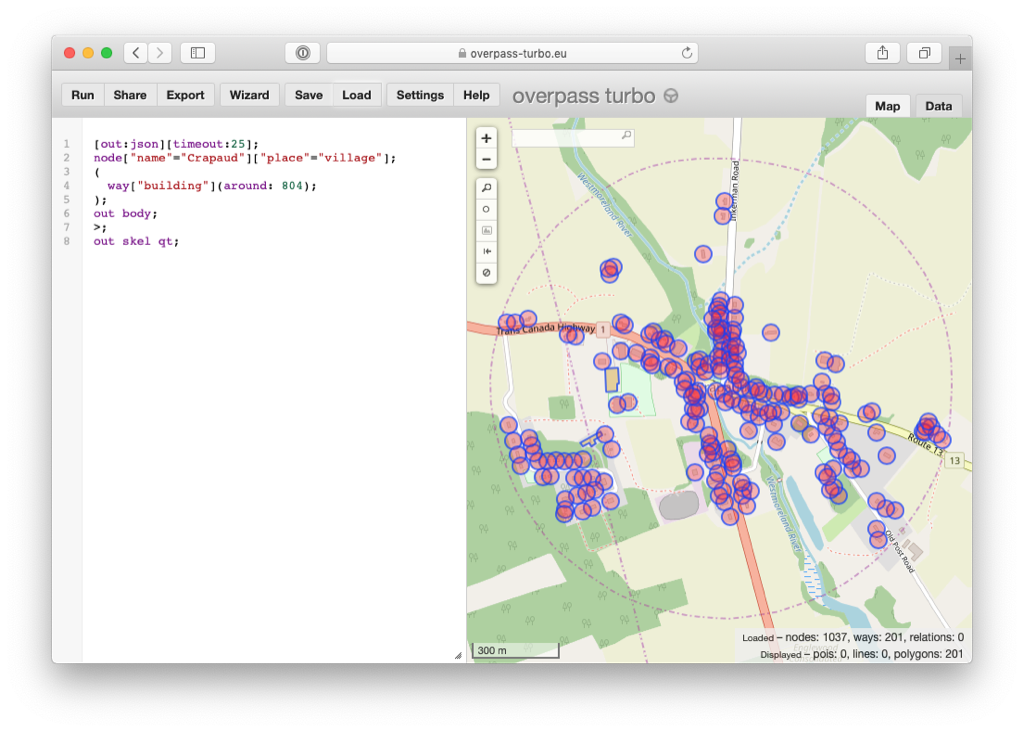

With the centre of Crapaud now fixed (at least close to) its proper location, and with the work I’ve been doing all winter long to fill out the roads, buildings, driveways, sheds, trees, rivers and forests of Crapaud in OpenStreetMap, I can now use the lovely and powerful Overpass Turbo tool to do some interesting things.

For example, here’s a query to extract all of the buildings in the village:

[out:json][timeout:25];

node["name"="Crapaud"]["place"="village"];

(

way["building"](around: 804);

);

out body;

>;

out skel qt;

The key part here is the (around: 804), which says “include everything within 804 metres of this node.”

It so happens that 804 metres is 0.5 miles. So this says, in other words, “in Crapaud.”

On a map this looks like this:

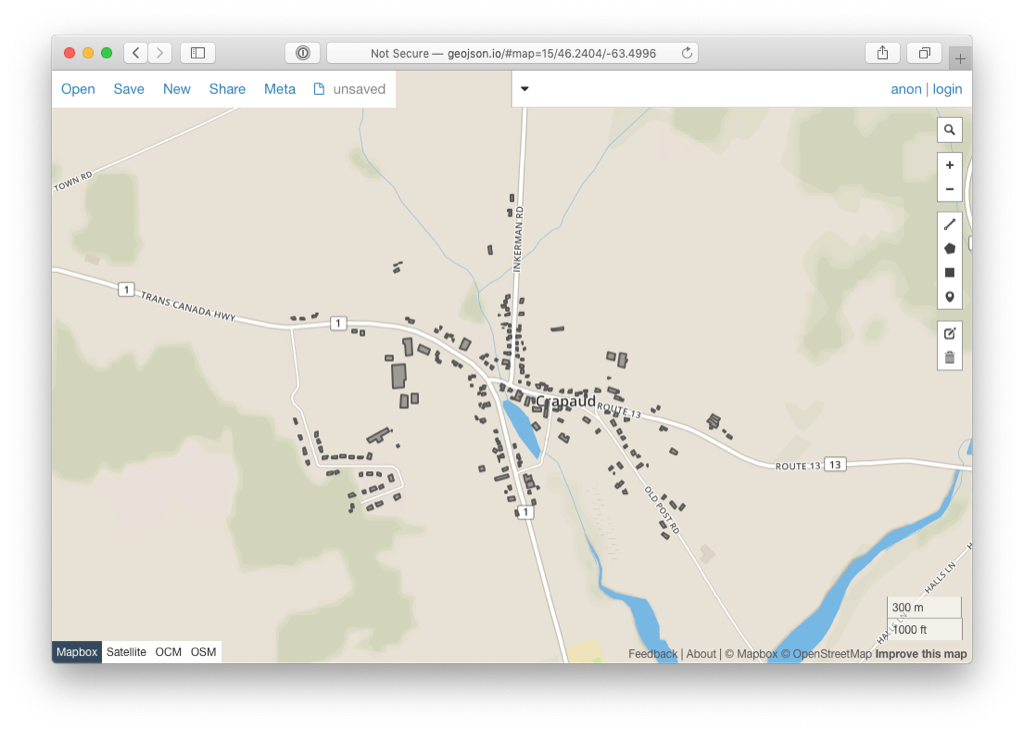

Exporting the results as GeoJSON results in a file that can then be imported into geojson.io:

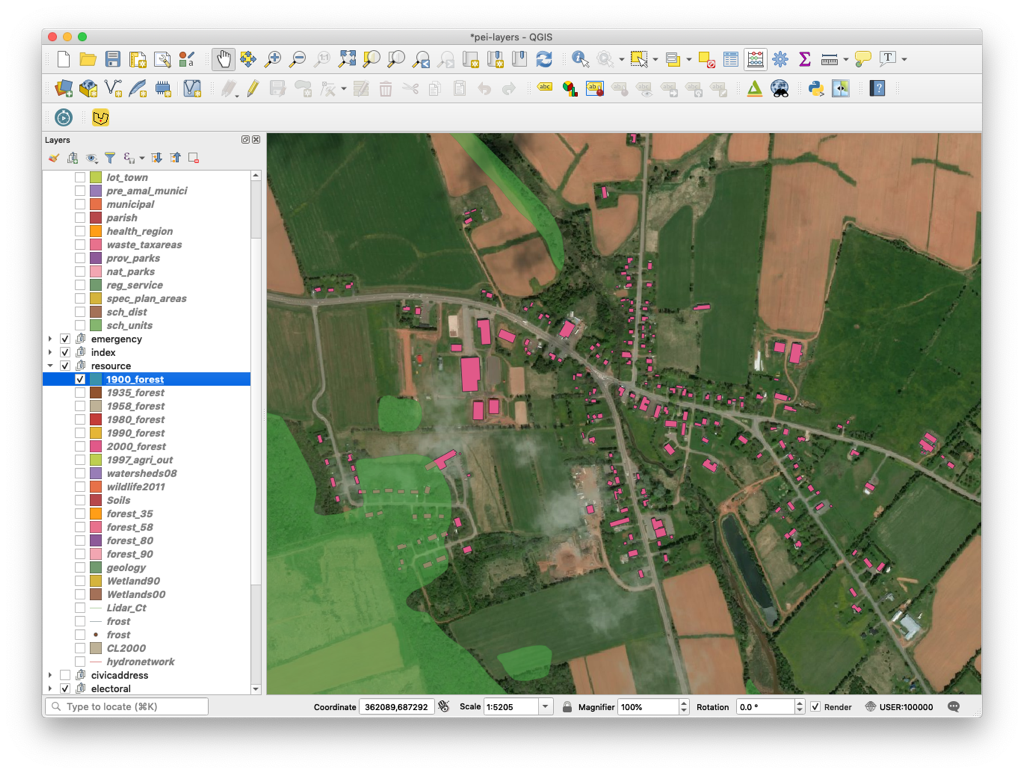

Or I can import the GeoJSON file into QGIS, and visualize it with public GIS data, like the 1900 forest layer, something that shows that the subdivision of Sherwood Forest (in the lower-left) used to actually be a forest:

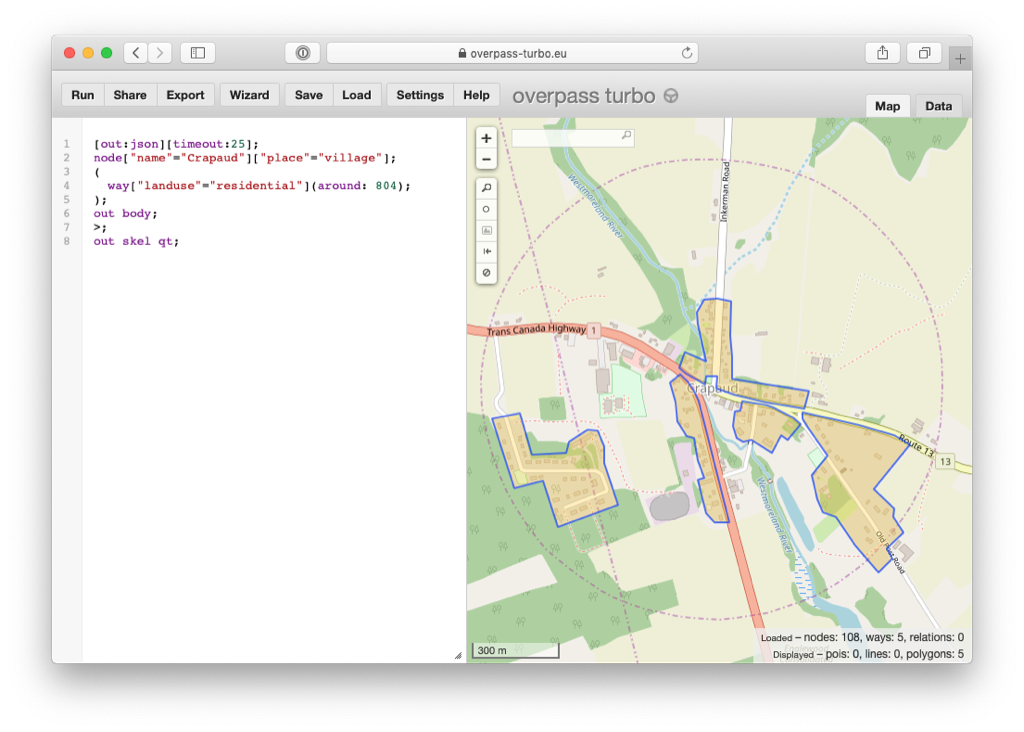

But it’s not only buildings: this query shows polygons where residential land use has been tagged:

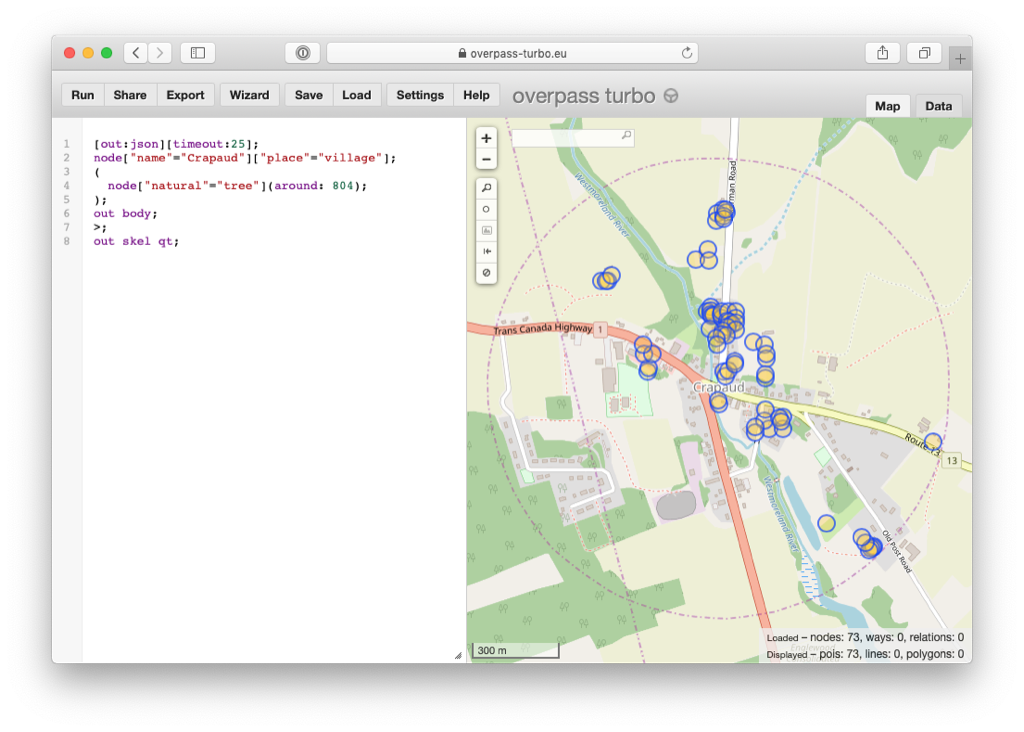

And this query extracts all the points marked as individual trees (as opposed to areas marked as “wood”):

I’ve so long thought of OpenStreetMap as a map, and of course it is that.

But it’s also a database with a powerful set of open tools that use open formats, meaning that the effort to keep the map up to date has all manner of unintended other benefits.

Longtime readers will recall that in 2010, thanks to the good graces of my friend Joan, I came into possession of the tiny letterpress that was formerly the heart of the Prince County Hospital print shop.

In addition to the Adana Eight Five press itself, there were various bits and bobs of letterpress type, spaces, and ornaments, much of it stored, as befits its former home, in medical specimen jars.

One of the items I purchased on my visit last month to the Museum of Printing in Massachusetts was a small font of sans serif type; at the time I assumed it was 12 point, but, taking it out for a ride this morning I realized it was 10 point. And that it didn’t include anything other than em spaces for spacing material.

I had an inkling that, somewhere buried in the boxes of letterpress ephemera that I’ve accumulated over the last decade was so 10 point spacing; I was right: in a pink Starplex specimen jar on the back of my lowest shelf I found exactly what I needed.

Thank you, Joan. And thank you Prince County Hospital print shop.

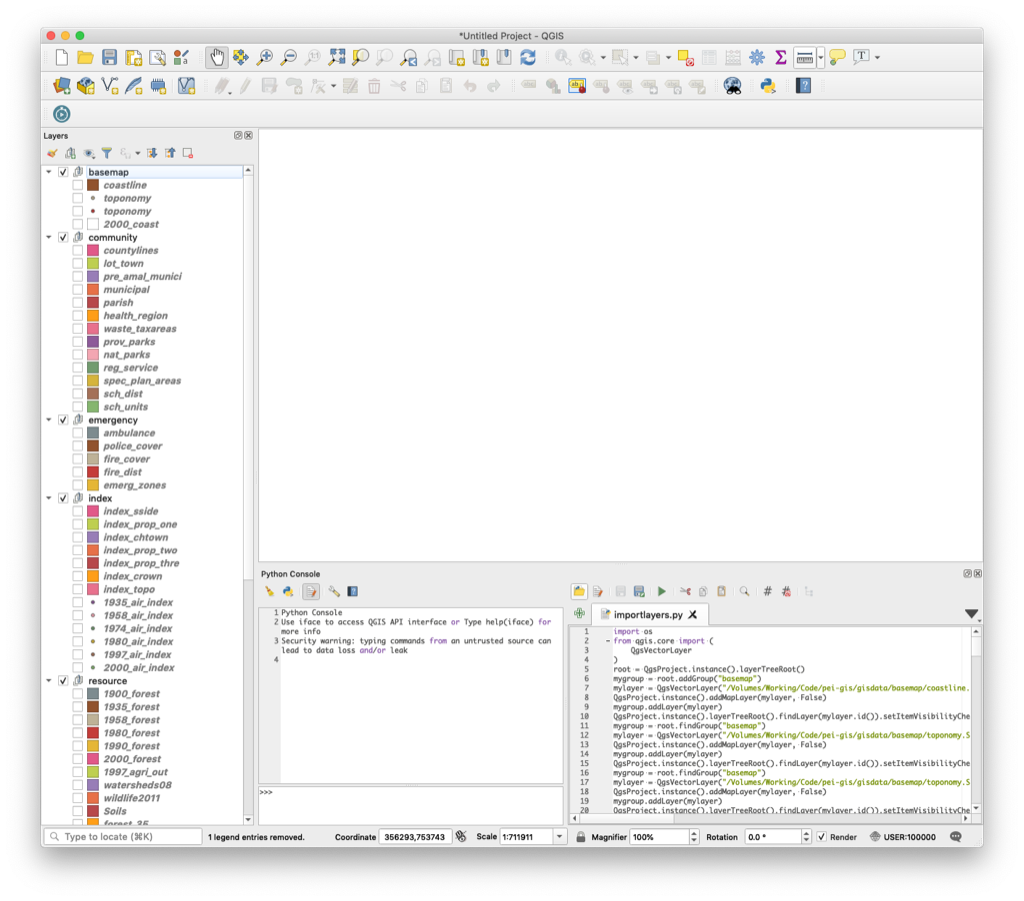

Back in 2011 I wrote a script to automate the scraping of the public GIS layers that the Province of Prince Edward Island makes available.

I’ve updated this script now–download it here–to handle the now blessedly simpler way the downloads work now (you don’t need to register to download any longer), and I’ve added the generation of a PyQGIS script that will automatically load all the downloaded layers into a QGIS project, ready for entertainment and delight.

We are watching a livestream of the ECMA folk stage at St. Paul’s Anglican Church across the street.

Our bandwidth at home is beamed across Prince Street from the Reinventorium (in the basement of the Parish Hall of the selfsame church) into an Apple Airport Extreme upstairs, which has an Apple Airport Express extender downstairs that Oliver’s MacBook Air in using for his wifi.

Oliver’s got the livestream playing on his laptop, and is streaming it to our Apple TV.

The Apple TV is connected to our 20 year old analog Sony Trinitron using an HDMI to RCA converter.

Where we’re watching music being performed in the church. Across the street. As it’s happening.

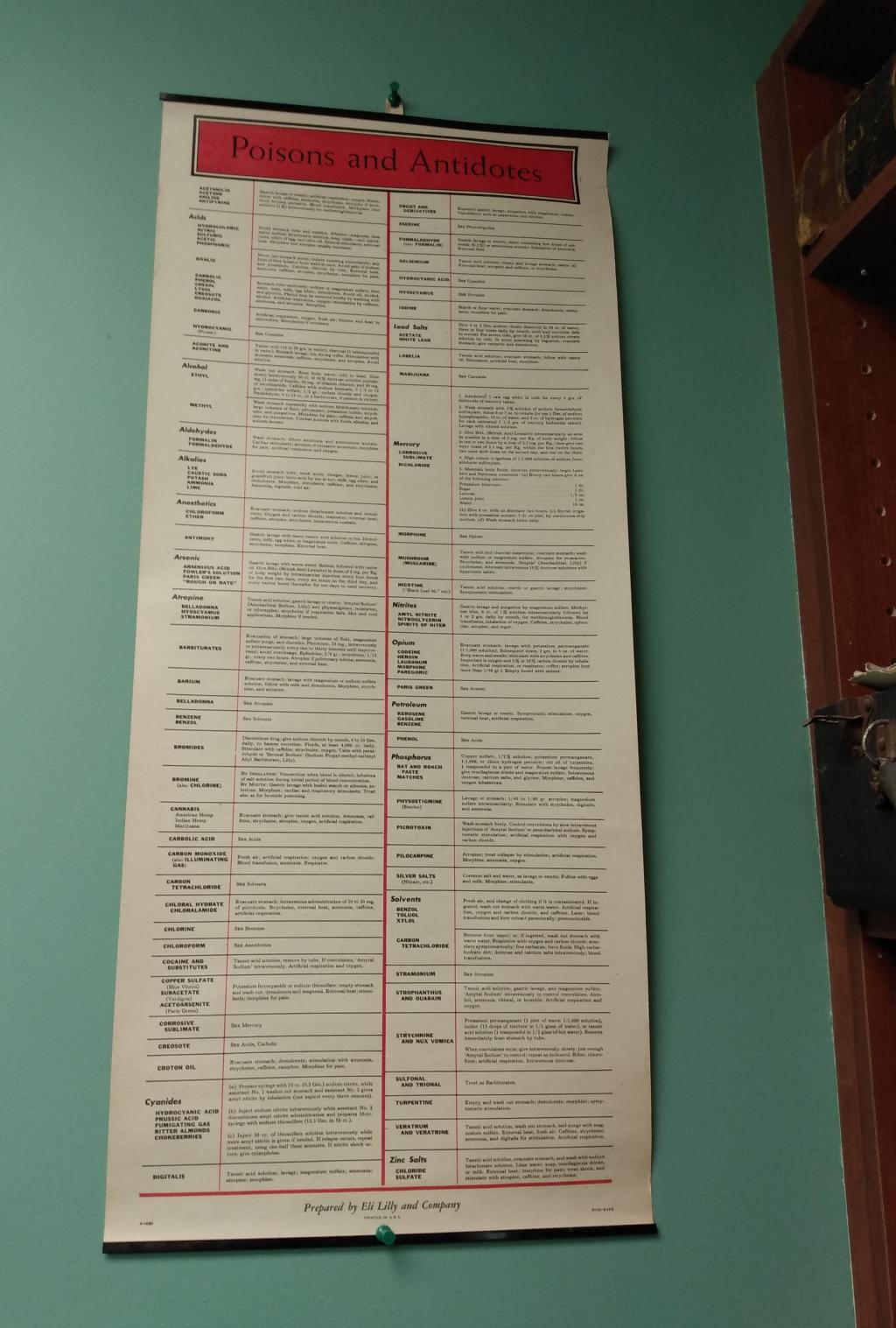

My family doctor has this chart on the wall of one of his examining rooms, one of an interesting collection of old medical artifacts.

I’m deeply suspicious that the cure for cannibis poisoning includes strychnine, itself a poison that is “a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents.”

That seems like a trick.

Blackbird, by The Beatles, sung in Miꞌkmaq by Emma Stevens at Allison Bernard Memorial High School in Eskasoni, Cape Breton.

See also Kalolin Johnson – We Shall Remain (It Wasn’t Taken Away), Emma Stevens – My Unama’ki (My Cape Breton), and Kalolin Johnson – Gentle Warrior (featuring Devon Paul and Thunder Herney), all from the same school.

Two Weeks, from The East Pointers, is one of those songs that instantly and naturally finds its place in the canon, filling a void we didn’t know existed.

It also happens to include what I believe to be the first reference to Charlottetown Airport’s IATA code, YYG, in a song lyric:

Monday morning, minus eighteen

Another WestJet, YYG to Calgary

I’d always knew she’d get used to me leaving someday

This solves the perplexing problem of Charlottetown not rhyming with anything.

The song was awarded Song of the Year at the East Coast Music Awards last night, well-deserved recognition.

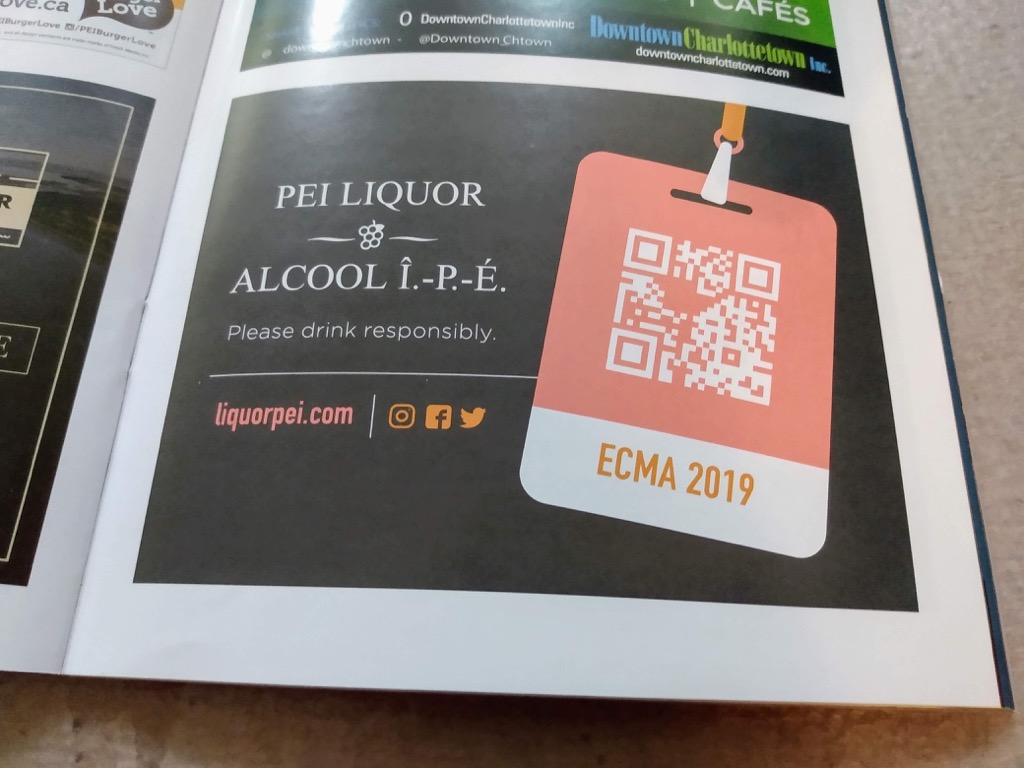

On page 73 of the 2019 East Coast Music Awards program there’s a half page advertisement for the PEI Liquor Control Commission:

You will note that a QR Code figures prominently in the design of the ad; while leafing through the program this morning I noticed this, and I pulled out my phone to see what was encoded therein.

For reasons perhaps having to do with the QR Code’s non-standard white-on-salmon presentation, I couldn’t get it to scan; to do anything with it I needed to take a photo of the ad and then doctor the photo on my Mac, inverting the colours to be dark-on-light. Once I did that I could scan the code from my phone, where it unfurled into a link for Shopify’s website:

I alerted the marketing department at the PEI Liquor Control Commission, and their response was that it was “a stock image that was used to create the ad for the ECMA program, and was not intended to be used as a functional QR code.”

While we all share a laugh about the folly of our government’s liquor regulator accidentally advertising for Shopify, there’s a more profound revelation to be gleaned here, and that is that QR Codes, always questionable to begin with, and of so limited a practical utility as to approach none, have now become digital tchotchkes so meaningless that there is apparently very little risk in dropping random ones here and there, safe in the knowledge that nobody’s ever going to scan them.

While we all share a laugh about the folly of our government’s liquor regulator accidentally advertising for Shopify, there’s a more profound revelation to be gleaned here, and that is that QR Codes, always questionable to begin with, and of so limited a practical utility as to approach none, have now become digital tchotchkes so meaningless that there is apparently very little risk in dropping random ones here and there, safe in the knowledge that nobody’s ever going to scan them.

It is May Day, and thus the start of the tourist season in Charlottetown, part of which involves turning Victoria Row back into a pedestrian-only thoroughfare.

After many years of using bollards, the City of Charlottetown has changed to using lockable gates this year, complete with a garish sign:

And so, for yet another year, my protests that we should sign positively not negatively are ignored.

Set aside the ugly and ill-fitting sign itself, as I suggested in 2017 the message here should be Pedestrians Welcome – Street Closed to all Vehicles.

The problem with the messaging this year is that it’s a lie: the street isn’t closed, it’s just different.

I am

I am