I’ve been experimenting with ownCloud on my Raspberry Pi as an alternative to Google (for contact and calendar sync) and Dropbox (for file sync). Because of the contrained resources of the Raspberry Pi this setup doesn’t exactly fly like a rocket, but it works, so far, and I’m happy to have my sync repository on my desk as opposed to in a murky bunker in place unknown.

I installed the stock Raspbian image and then followed the steps in this helpful guide to get Nginx, PHP and ownCloud running on the Pi. It worked without issue; the only thing I diverged from is that I installed ownCloud six instead of the version 5 mentioned there.

Part of the helpful guide involves creating a self-signed SSL certificate to allow traffic to and from the Pi to be encrypted. Setting up OS X Calendar sync with this certificate in place didn’t present a problem: I simply agreed to trust the certificate. Same thing in my iPad.

On Firefox OS, however, there’s no such option, and when I tried to add my ownCloud calendar as a Caldav account I got an unhelpful generic error message. Looking at the output of adb logcat as this failed I saw the cause was, indeed, SSL related:

The certificate is not trusted because it is self-signed.

Fortunately there’s another helpful guide that walked me through the process of adding a new root certificate to my Firefox OS device. A few notes on that process:

- I didn’t have the Mozilla NSS certutil binary on my Mac, and there didn’t seem to be a non-complicated way of compiling and installing it, so I did all the certificate-mangling work on an EC2 host where it was pre-installed.

- In the text where it says “<CAName>”, you simply make up a name for your personal “certificate authority,” like “Reinvented” or “PeteCo”.

- The references to “<CAFile>” are to the cert.pem file you generated on your Raspberry Pi.

Otherwise, the process went exactly as advertised, and once I restarted the Firefox OS device (and this was a necessary step), I was able to add my ownCloud Caldav server to the Calendar app without issue, and after a brief pause for sync my calendar showed up:

I was cleaning out an old long-forgotten S3 bucket this morning and came across the video of the demo session from PlazeCamp, the developer hackday we held at Plazes back in January of 2008. An interesting pan-European crowd showed up to hack on the then-new Plazes API, and in this demo session we all showed off our day’s work.

Hard to believe that was 5 years ago. The Wii Plazes that I demonstrated (complete with a public unveiling of my quickly-changed-thereafter password) is still online, although, without a Plazes API to send anything to, it doesn’t do much.

Through one of those rabbit holes that the web is so good at conjuring I came across the heart-wrenchingly-good tract The Playwork Primer (PDF) this morning.

When I was young I wanted to be a teacher, and so I started down the path to becoming educated as a teacher Trent University. Our final assignment was to write an essay expressing our “philsophy of education.” I never handed it in (I never started it). Which is why I’m not a teacher.

In The Playwork Primer, however, I find what amounts to the best description of my philsophy of education that I’ve yet to come across:

We aim to provide a play environment in which children will laugh and cry; where they can explore and experiment; where they can create and destroy; where they can achieve; where they can feel excited and elated; where they may sometimes be bored and frustrated, and may sometimes hurt themselves; where they can get help, support, and encouragement from others when they require it; where they can grow to be independent and self-reliant; where they can learn—in the widest possible sense—about themselves, about others, and about the world.

Those words are from Stuart Lester, Senior Lecturer in Play and Playwork (!) at University of Gloucestershire in England.

If you’re interested education and play and children’s lives, I encourage you to grab a copy of The Playwork Primer: it’s an inspiring guide. It’s hard not to love a piece of writing with subheadings like “Cloak of invisibility,” “Cardboard boxes,” and “Commodification of play” (and that’s only the Cs). One of my favourite sections is “Secret spaces”:

This is a phrase used by Elizabeth Goodenough to describe the hideaways that children need to create or discover and to have safely within their control. Without these private places where their inner playful lives can be exercised, children have little opportunity for many different types of play.

Morgan Leichter-Saxby asks, in her work on forts and dens, without the opportunity to experience privacy how on earth can children discover a sense of their private selves and personal worlds? She writes:

To be by oneself, in a place that feels safe and unadulterated, to have time and space to dive into the depths of the playing that is an intrinsic drive within you, to step at once aside from and yet deeper into the world as you experience it, that is when and where the richness of the play that is possible ripens to fruition.

The notion that there’s someone whose professional practice includes “work on forts and dens” is amazing to me.

One year ago today I started archiving the energy load and generation data that the Province of PEI makes available at 15 minute intervals on its website. I’ve collected 34,471 data points (if you like you can grab the entire archive as a CSV file for your own analysis).

I’ve been using this data, over the course of the year, to help build my own “peripheral awareness” of the Island’s electricity situation, using tools like this visualization of load vs. generation and this simple gauge showing how much of our load is being met by the wind.

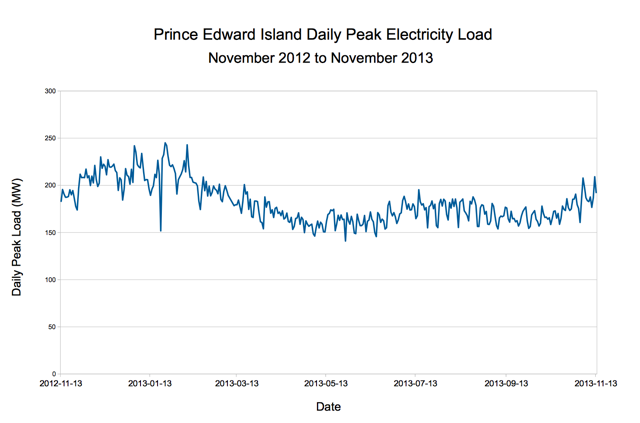

I’ve had conversations with staff at Maritime Electric and the PEI Energy Corporation to try to better understand these numbers, and one of the things that I’ve learned is that “peak load” is an important number when talking electricity: utilities like Maritime Electric are contractually obligated to be able to meet the peak load – the maximum amount of electricity we might all collectively call for at any given time – and they have to build generation capacity or have a reliable import source to meet that obligation.

Over the last 365 days the Island’s peak load came on January 23, 2013 at 245.07 megawatts (MW). We had 75 days where the daily peak load was more than 200 MW and the lowest daily peak was 140 MW on May 26, 2013. This late-January peak represents trend away from the traditional “Christmas lights peak” in December and, I am told, comes as a result of an increasing shift toward electric-source heating.

Here’s what that daily peak load for the last 12 months looks like on a graph:

These are important numbers for Islanders to know and understand because it’s the peak, more may any other factors, that drives the cost (and complexity) of meeting our electricity needs.

The report of the PEI Energy Commission is an excellent resource in this regard.

From that report, for example, I learned that the yearly peak in 1977 was 95 MW – meaning that our peak in this year was 2.5x higher than our peak 36 years ago.

And that the capacity of the electric cables to the mainland is 200 MW. Which means that when the load goes over 200 MW – as it did on 20% of days over the last year – we need to make up the difference from local generation, either fossil-fuelled or wind-generated.

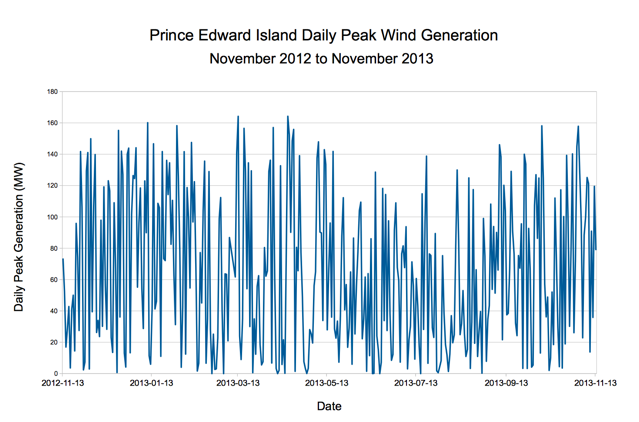

The wind, of course, wasn’t a factor in our energy mix back in 1977 and now it’s a significant one. But, as the graph below, showing the daily peak wind generation over the last year, shows, the wind is variable:

There have been some fantastic days for wind generation – 12 days, for example, where the daily peak was more than 150 MW – but also some bad days for the wind: on 59 days the daily peak was 10 MW or less.

That said, there were 1,546 intervals of fifteen minutes or less over the course of the year where wind generation exceeded load, making PEI, temporarily, an energy exporter. Granted, most of these intervals were in the middle of the night; but on October 8, 2013, for example, we were generating 56 MW more than we were using at 3:00 a.m.

It is de rigueur in energy and “personal analytics” fields these days to believe that the mere fact of monitoring behaviour affects behaviour: if you keep track of how many steps you’re walking every day, you’ll be more inclined to walk more steps every day.

I feel like that’s supported by my own electricity-using behaviour: I seems like I’ve become a more responsible electricity consumer since I started paying attention to PEI’s energy mix – like I’m turning off lights more often, unplugging things that don’t need to be plugged in.

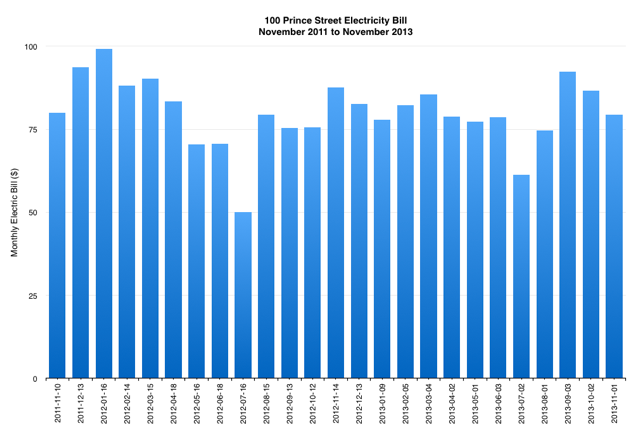

So far, though, the evidence doesn’t really bear this out: here’s a chart showing our monthly electric bill at 100 Prince Street for two years, one in which I wasn’t paying attention to electricity and one in which I was:

Our total yearly bill for November 2011 to November 2012 was less than a dollar different than the bill for the following year (although, to my credit, the rate per kilowatt hour did incease, on our March 2013 bill, from 12.05 cents to 12.41, so it’s not quite an apples-to-apples comparison).

I’ll keep watching, and keep turning things off: knowing that my vigilance hasn’t really made a dent, at least for a while, will make me ever-more-vigilant.

When I read about Catchbox, a “throwable microphone,” on the Alibis for Interaction blog in September I didn’t get it.

“What’s wrong with regular old microphones?”, I thought.

Then I went to Alibis for Interaction and I saw a Catchbox in action – used it even – and I understood.

Then, this weekend, at the StopCyberbulling conference I saw “regular old microphones” in use to take comments and questions from the audience and it all seemed positively barbaric.

Here’s what I get now, that I didn’t get before, about Catchbox:

- It moves itself around: you simply throw it to the person who wants to speak, and they throw it onward. You don’t need “microphone ushers” stumbling their way down the aisles.

- It shocks people using it out of “I’m asking a question at a conference”-speak: it doesn’t look like a microphone, so you don’t fall into the (boring old) role of someone asking a question. That difference is small, but it’s important.

- It’s fun to use, and fun to watch. It injects an element of whimsy into the proceedings.

- It spaces out the conversation: at this weekend’s event, with the “microphone ushers” moving the microphone around, questions tended to be confined to the areas they could easily travel to quickly, and then fanned out from there. With a Catchbox the next speaker can be far across the room, and the microphone can be there as quickly as it can be thrown.

- It’s obvious who “has the floor”: it’s the person with the bright pink (or orange or yellow or blue) box in their hand.

Having seen it work, I’m sold, and I’d encourage anyone who’s organizing an event that has an audience that you want to engage (or where you want to actively work to break down “audience” and “speaker” roles) to investigate. You can’t buy one yet, but you can rent one if you’re in Finland (or, apparently, Landskrona), and you can put yourself on the waiting list when they open up sales.

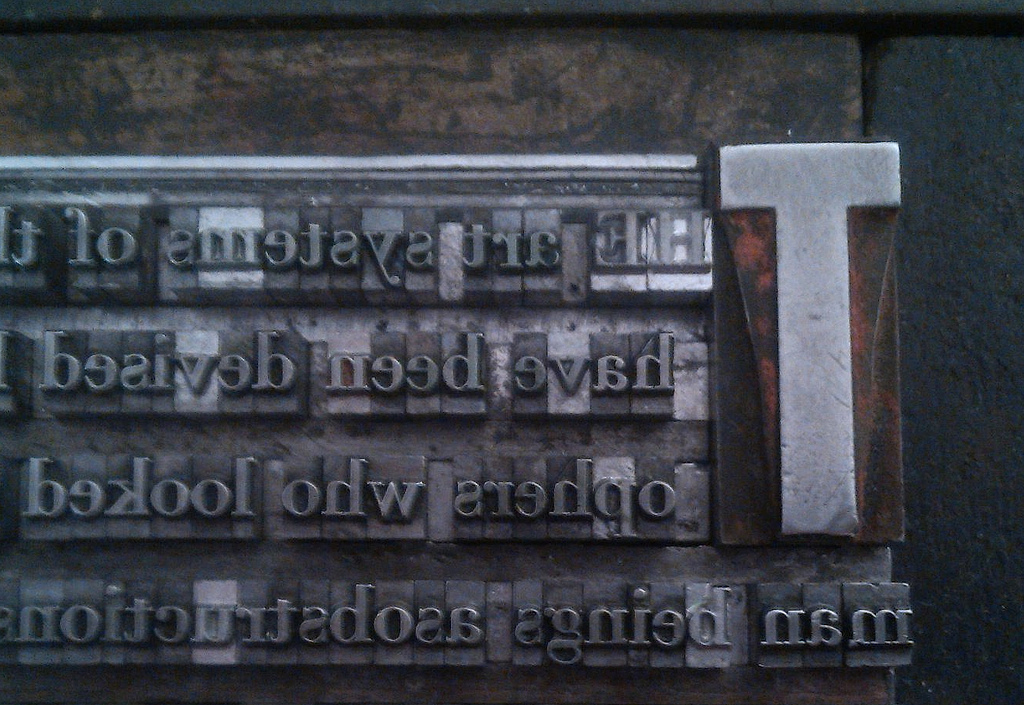

Applying what I learned from history along with some liberal interpretations of advice from my friend Fred the Printer, this has now become this:

I switched the drop cap from 30 point Univers to 48 point Akzidenz Grotesk, indented the second and third line by an en space, and switch the “he” in “the” to caps. It’s not entirely unpleasing.

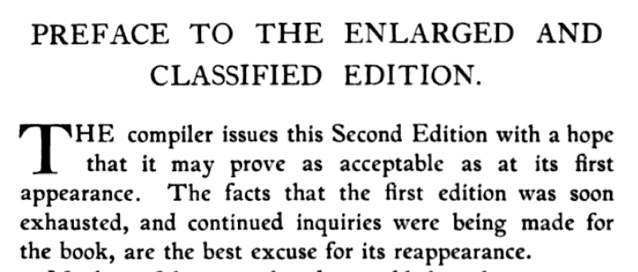

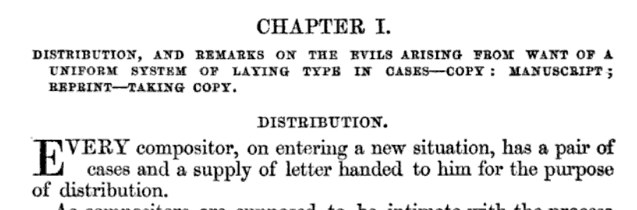

Google Books is a treasure-trove of books from the 19th century, and thus a good place to turn if you are, as I, setting metal type and trying to get a feel for spacing drop caps. Here are some examples I’ve found tonight showing some interesting variations.

Common to these is that (1) the second line is indented slighly, (2) the first word of the paragraph beyond the drop cap is set in small caps (or simply all in caps), (3) the drop cap itself has its cap height aligned with the cap height of the remainder of the first word and (4) there isn’t much regard for where the baseline of the drop cap falls:

The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower-garden

I’m working on setting an excerpt of the lecture that Oscar Wilde gave in Charlottetown in 1882, and using the opportunity to experiment with setting a drop cap for the first time:

I’m setting the body in 12 point Bodoni and the drop cap is 30 point Univers. I’ve done a lot of experimenting with the vertical position of the ‘T’, and I think I’ve found a sweet spot that lines up its baseline with the baseline of the second line of the body. I’m looking forward to seeing how this looks once it’s printed.

A few weeks ago my friend Daniel Burka wrote something that continues to resonate with me, a personal essay about endeavouring to be “more wholehearted.” He wrote, in part:

I’m often sarcastic about, well, anything. I frequently err on the critical side of critique in my design career. I smugly make comments about other people’s attire when I’m in the safety of my car. Heck, I’ve tweeted plenty and as we all know Twitter is greased with the bile of cynicism. And when I consciously stop and think about it, it’s almost always totally unnecessary.

I guess I get a short sugar rush of superiority by belittling someone else and cynicism masquerades as cleverness. Also, there’s nothing wrong with criticism when you’re critiquing someone’s work, but it’s so easy and encouraging to point out the positives too. More often than not, sarcasm, criticism, cynicism, and snarkiness stem from either knee-jerk habit or come from a truly destructive place that most of us forget is hiding inside us.

This was, in a sense, only something Daniel could write: I’ve always considered him a master of the witty retort, and it’s never been difficult to imagine him sitting around the Algonquin Round Table drinking scotch with Tallulah Bankhead and making fun of Dwight Eisenhower’s floppy ears.

While I would have no seat at the table – I’m not quick enough of mind – I certainly am no stranger to sarcasm, criticism, cynicism and snarkiness, as regular readers of this space will know.

I’m not quite ready to throw myself wholeheartedly into the wholehearted lifestyle – sarcasm is currency in my family, and I’m not sure how I would communicate with that out of my toolbag – but remembering that, so often, “cynicism masquerades as cleverness” is useful. Thank you, Daniel, for pointing that out.

I am

I am