Today was my final lecture of four in the Philosophy 105 course I’ve been guest-teaching this winter (see reports from lectures one, two and three). I’ve taken the students on a diversion from the regular text and the regular path through the “philosophy of technology, values and science” so today was an opportunity to try to knit the various tangents I’d gone on together. As my overarching goal for my four lectures was to drop into the world of “open” – source, data, government, society – as a philosophical approach to technology, using my own experiences as a jumping off point, I opted to use OpenStreetMap, the open project I’ve spent the most time lurking in, as the focus for today. And so we opened with The Map:

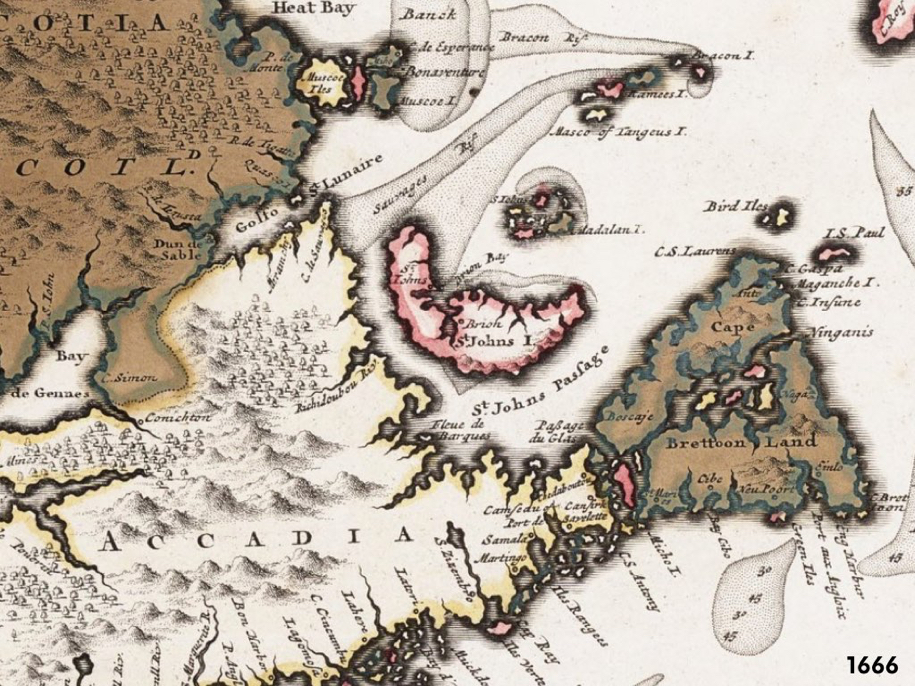

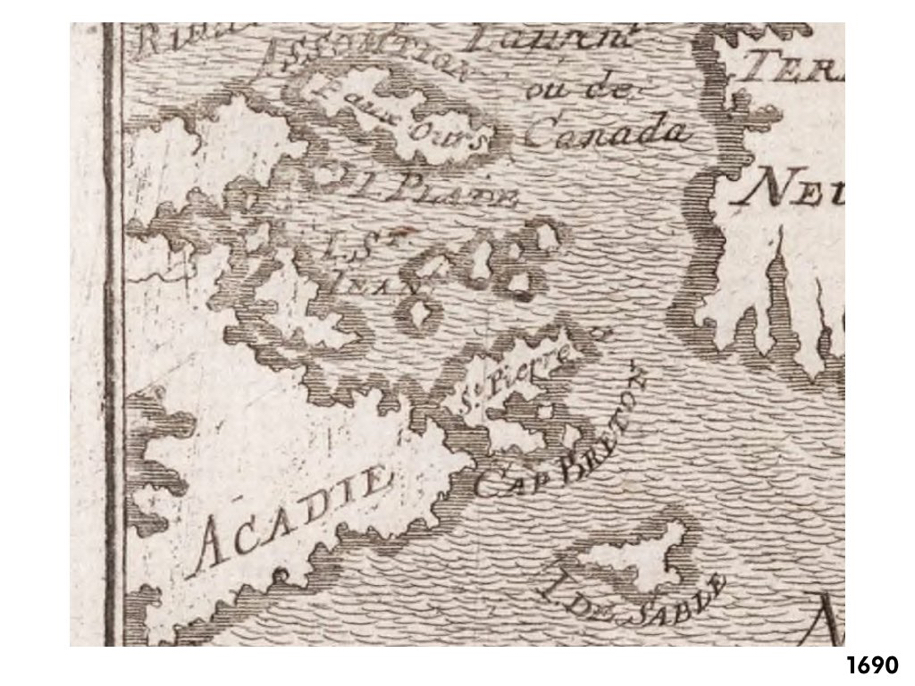

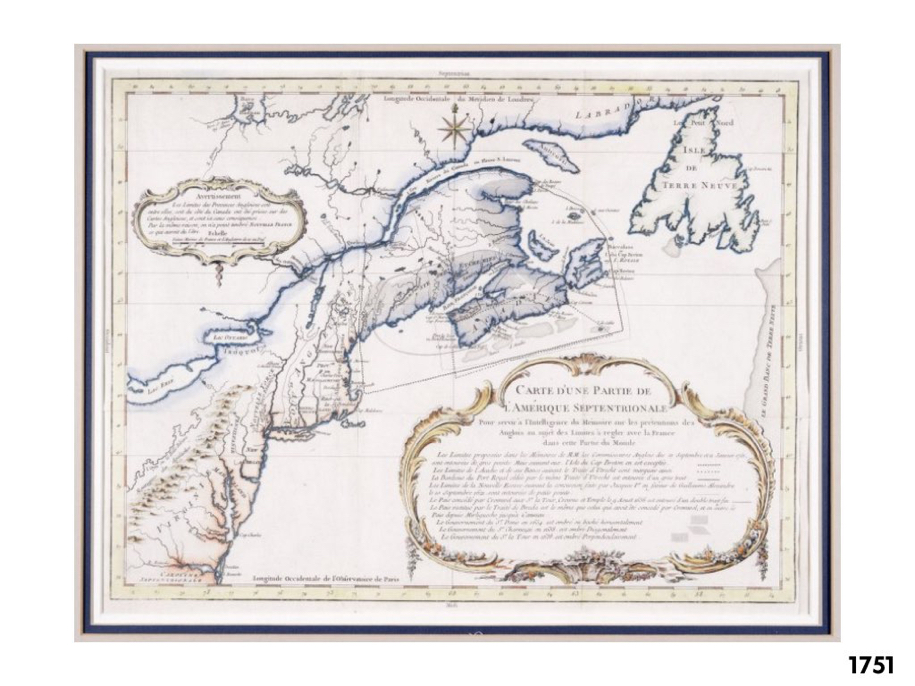

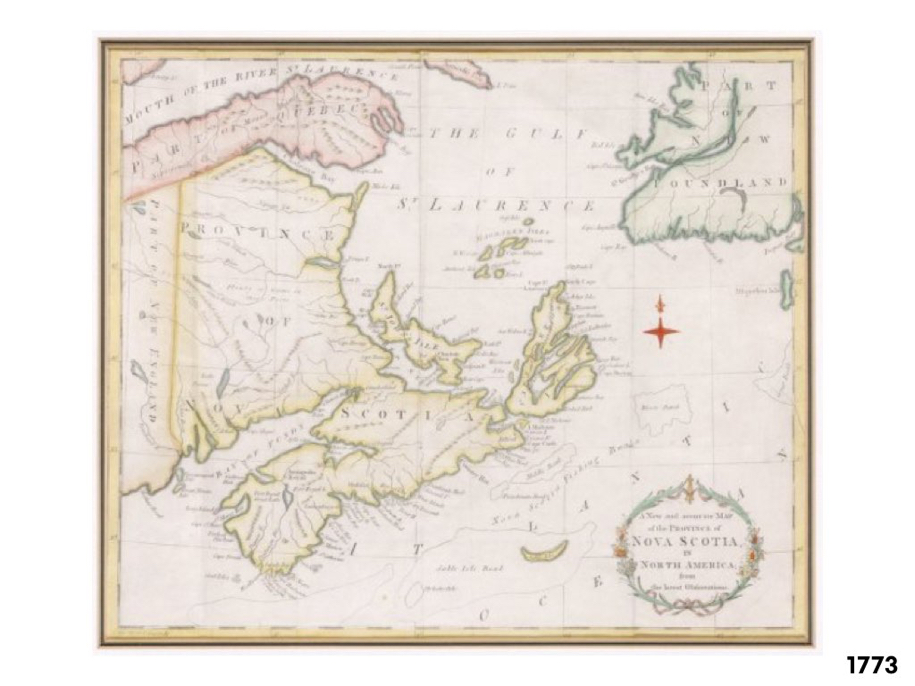

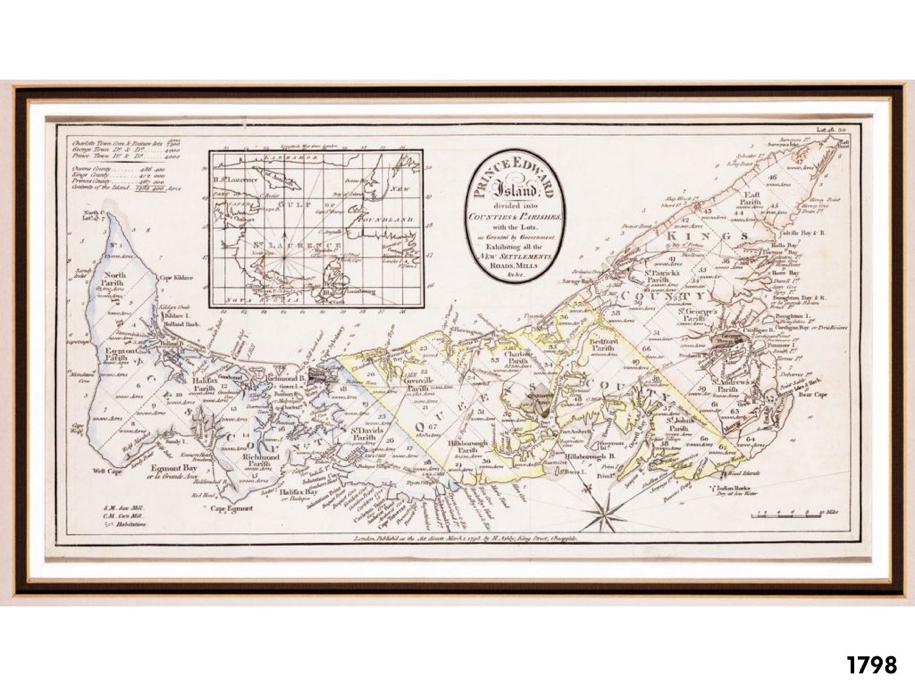

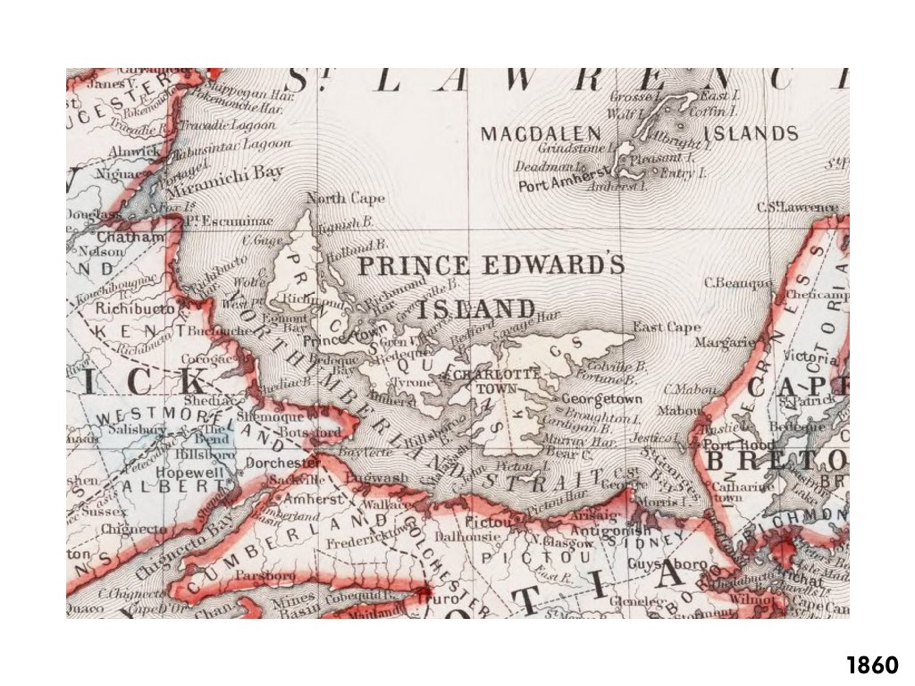

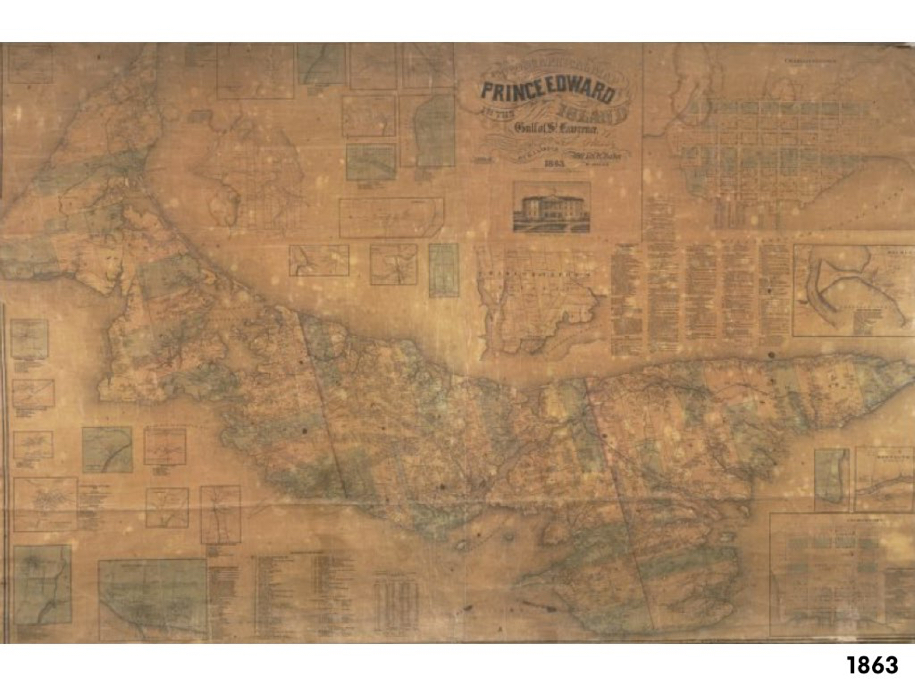

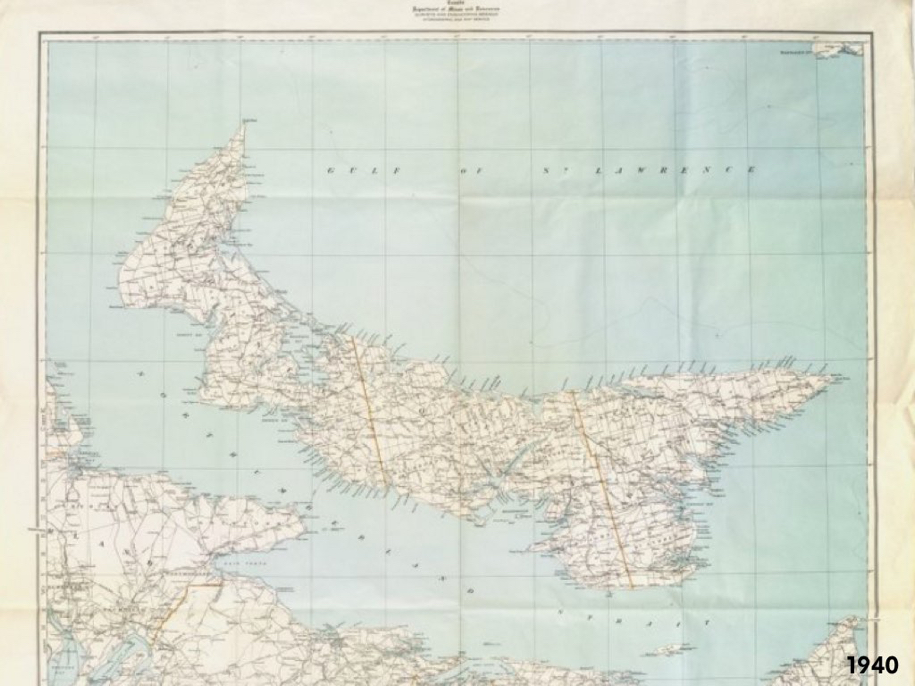

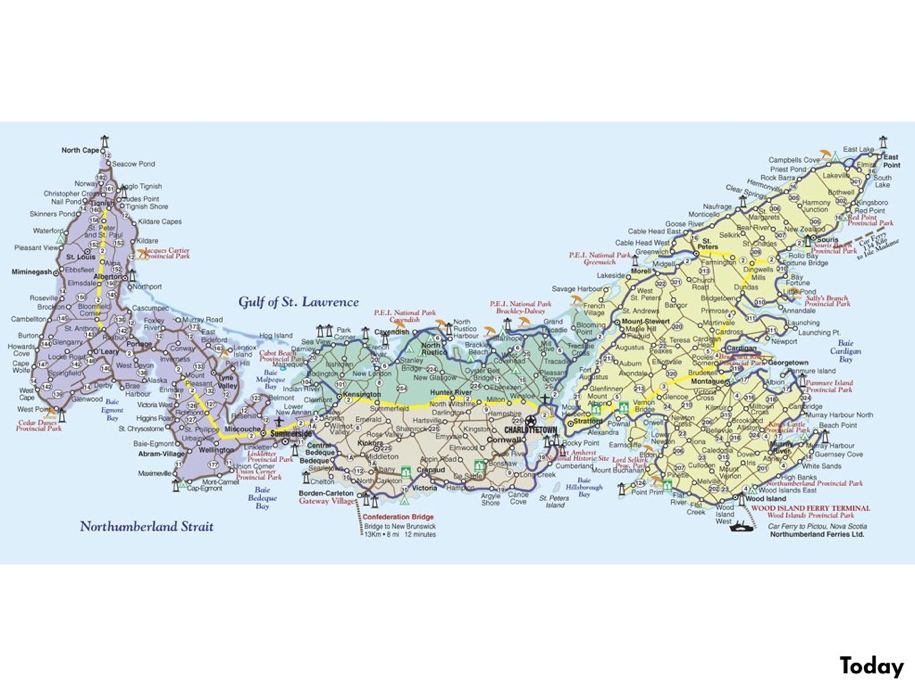

I then led the students through a visual history of maps of Prince Edward Island – helpfully mined from IslandImagined.ca – from 1666 to the current day:

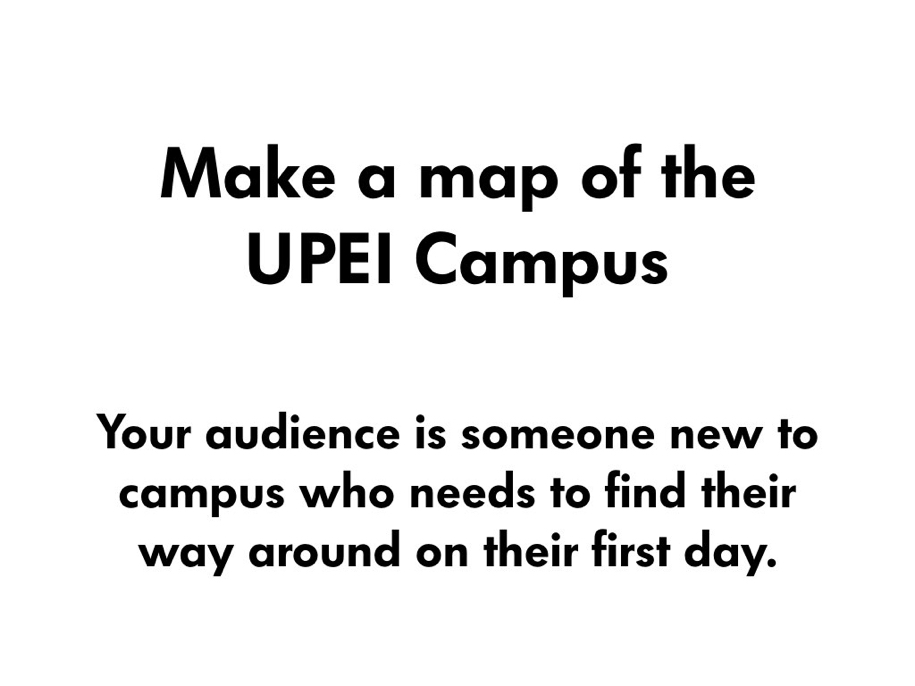

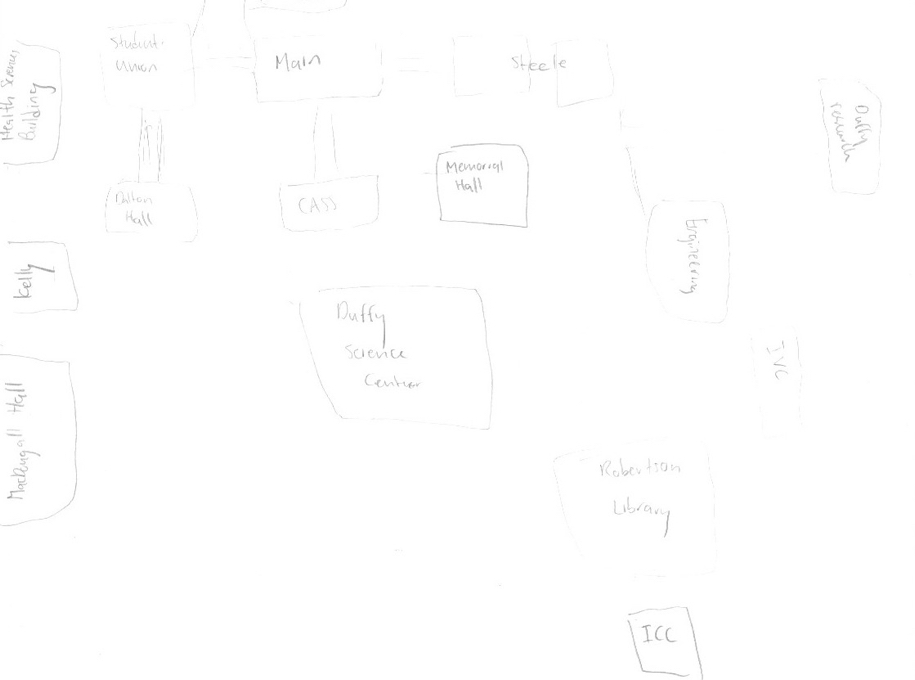

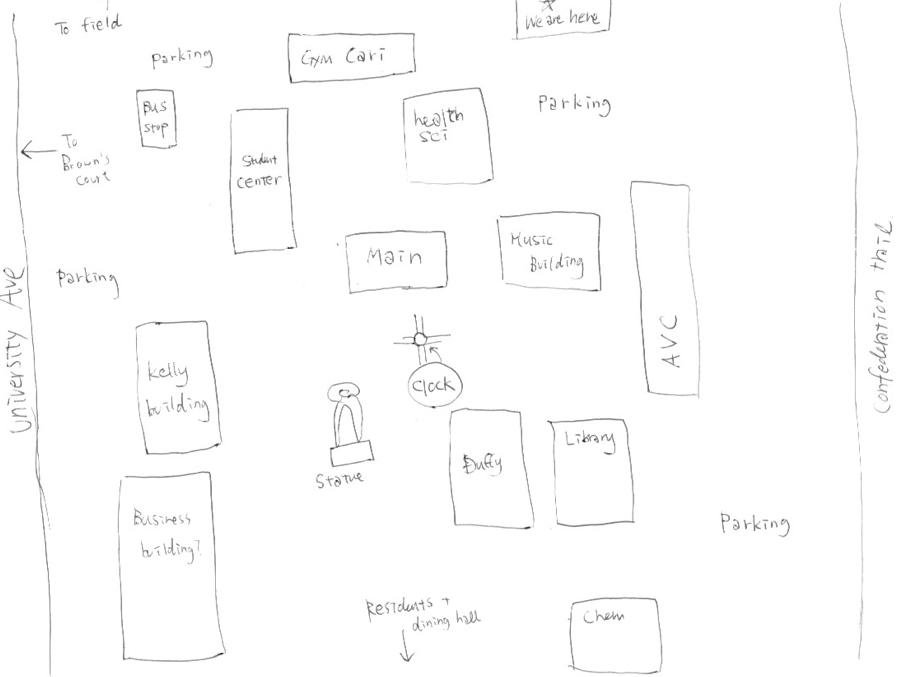

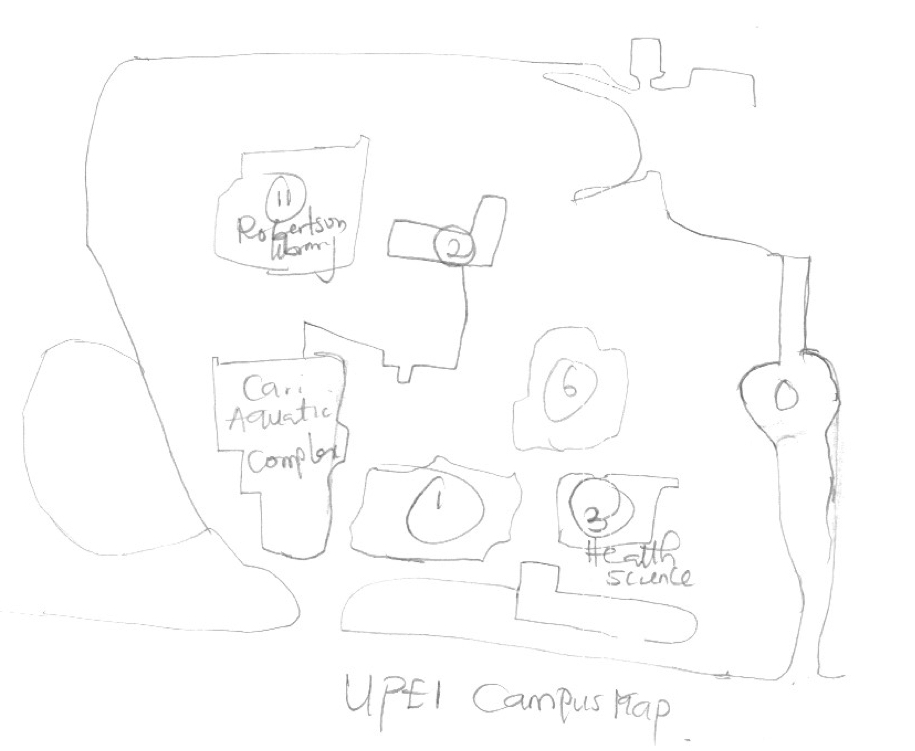

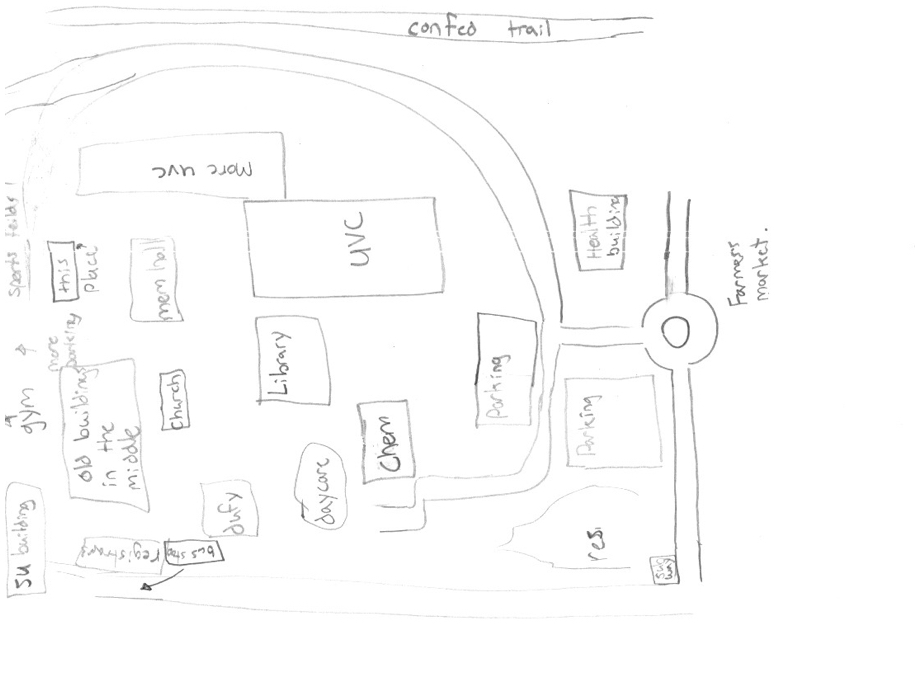

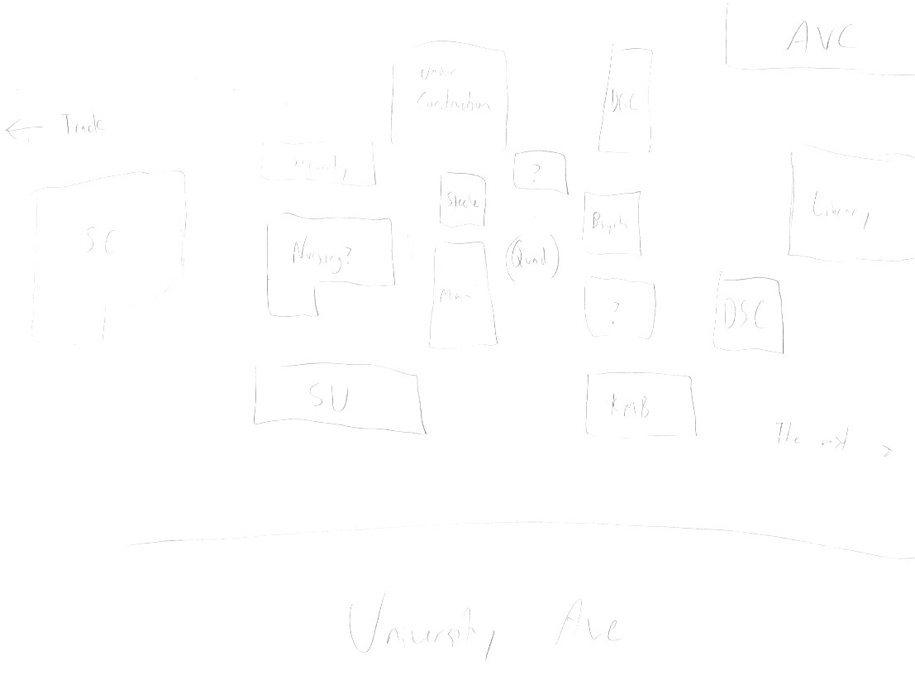

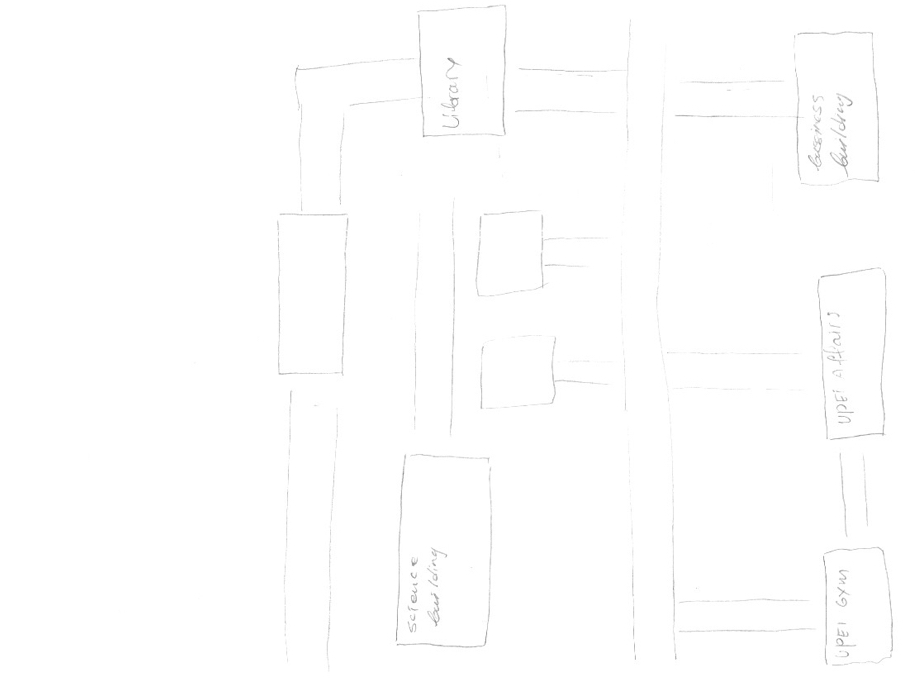

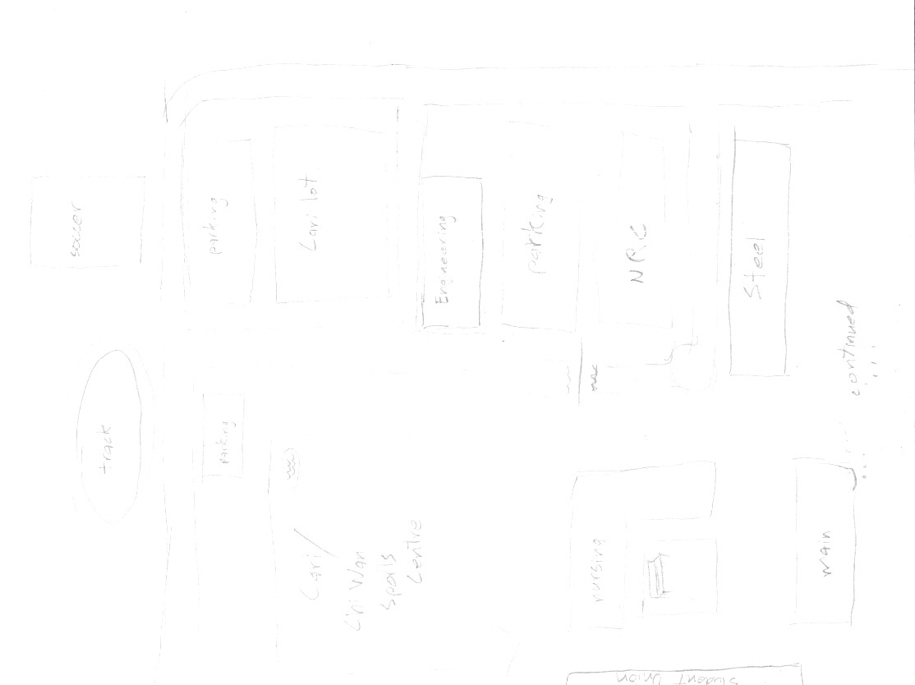

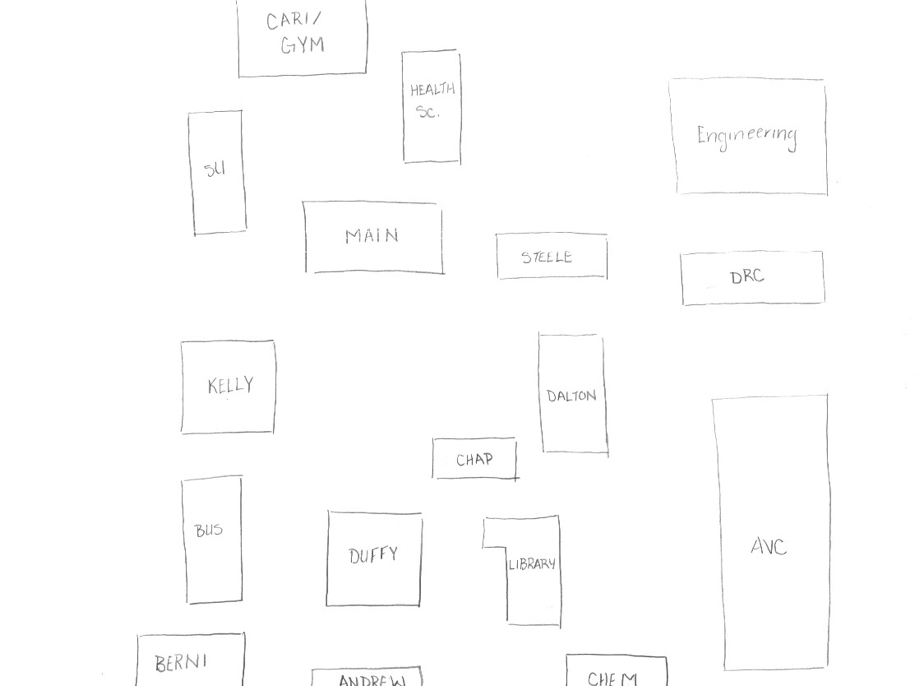

I wanted to reinforce that maps exist in a cultural context and a technology context: evolutions in our ability to measure, to communicate and to print all influence the maps we can produce, and the maps we can produce influence our mental model of where we live. In this spirit, I then presented the students with a quick challenge: take 5 minutes, a sheet of card stock and a pencil, and make a map of the University of PEI campus, suitable for handing to a new student who needs to get their bearings.

The results of this exercise – I gave them about 10 minutes to finish – were very interesting: 10 students prepared 10 very different maps, with different levels of detail, perspectives, orientations, levels of accuracy, style. I posted all of the maps on the whiteboard at the front of the classroom and asked them all to come up and take a look at them, and to compare and contrast their own maps to others. I didn’t need to say any more: the results proved the point that maps have politics, maps have limitations, maps represent the world view of the creator and the tools available to them.

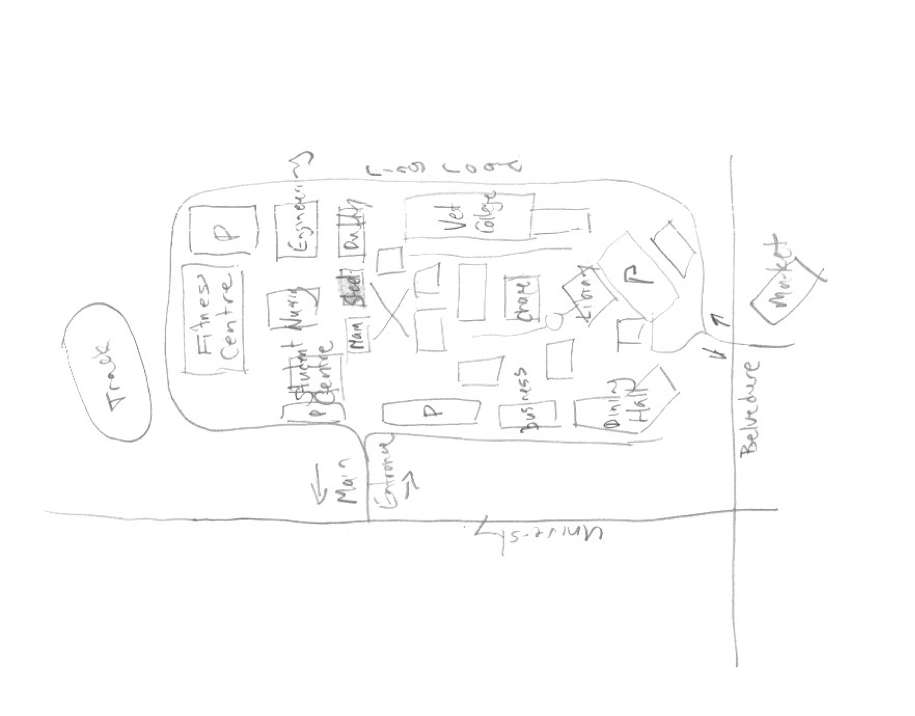

I threw my own version of the map into the ring for comparison (I created it at the same time as the students were creating theirs, and that in itself was a learning experience for me):

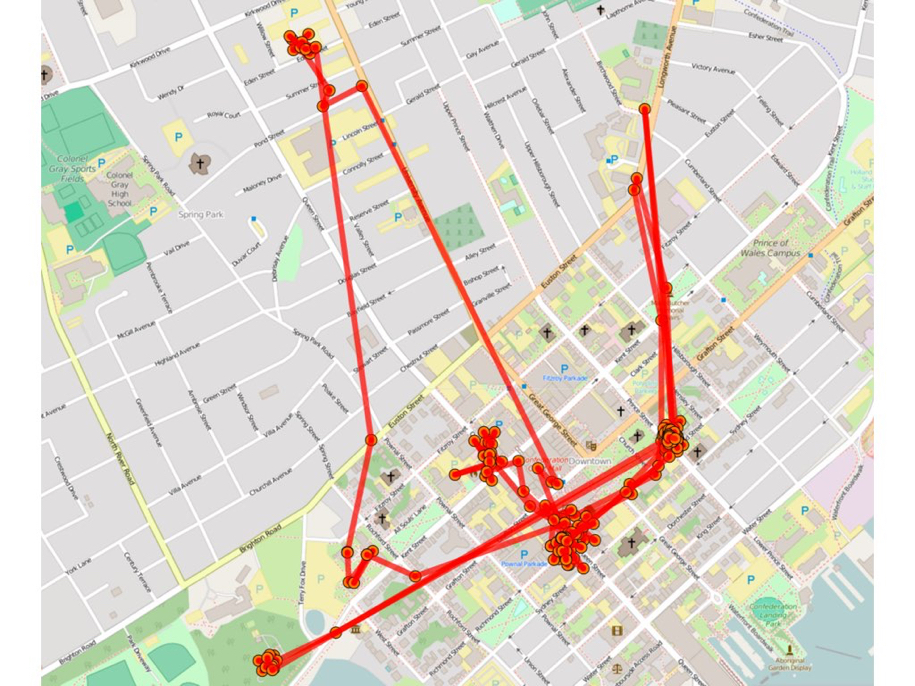

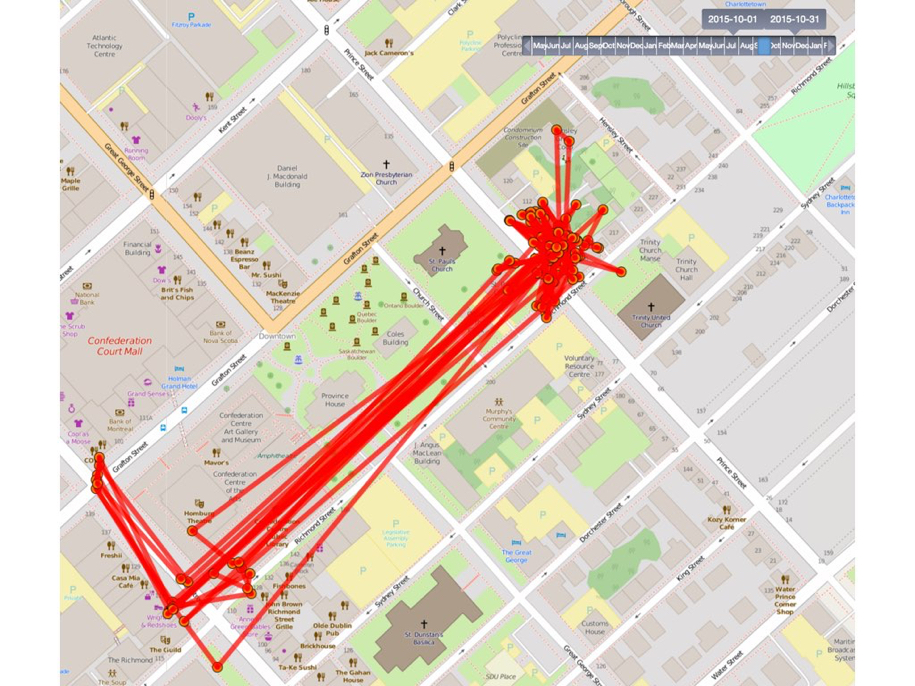

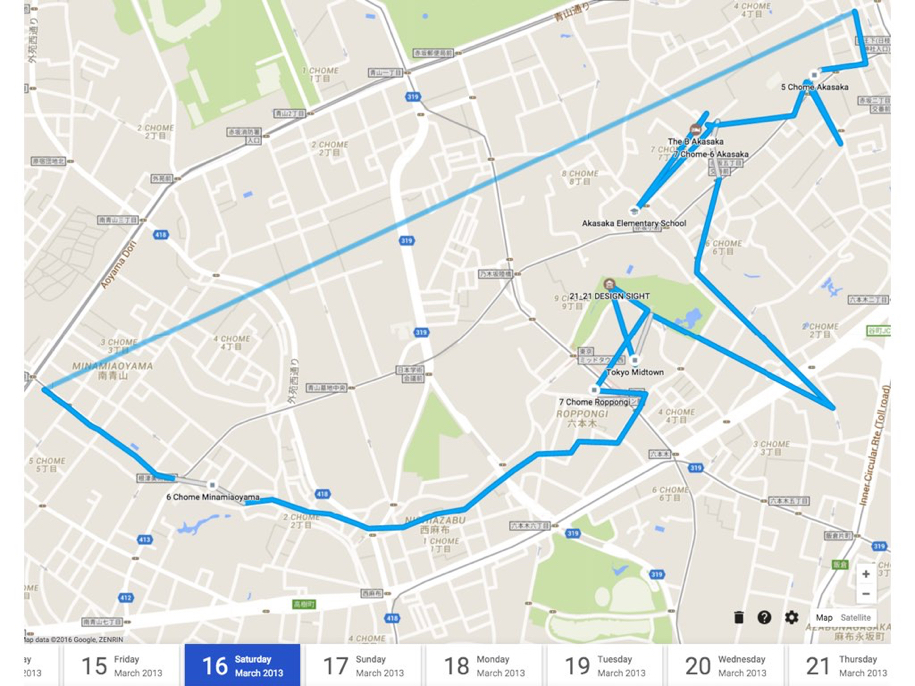

With the scene set, I then walked the students through a series of slides that illustrated how I leave a “digital breadcrumb” wherever I go, and how the collection of those breadcrumbs together tells a set of stories, and leaves a digital fingerprint of my passing:

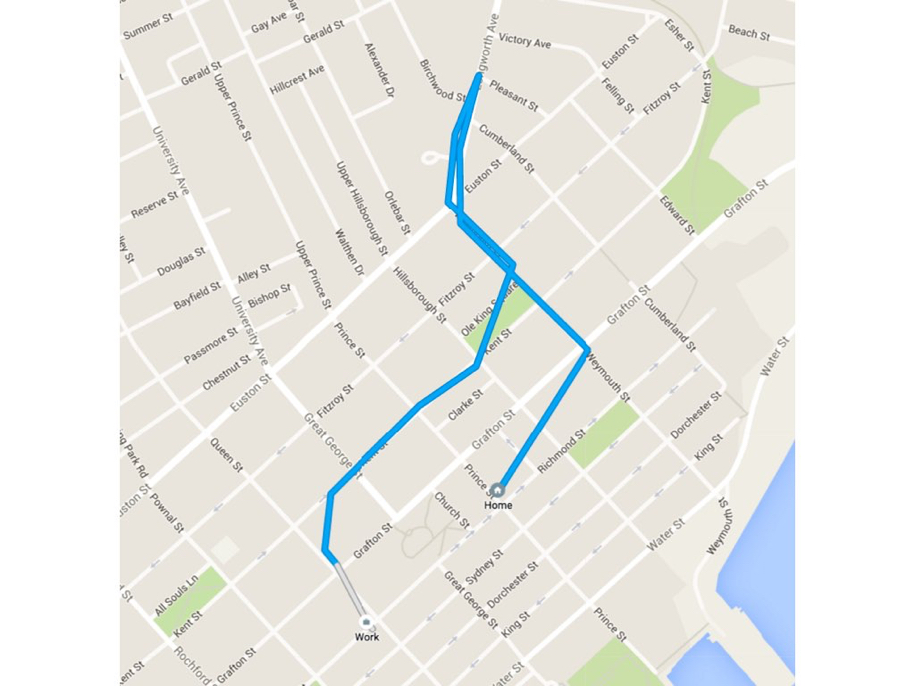

I then showed how the same data, from the same phone, also shared with Google, and thus merged with what Google knows about the world, can result in more meaningful (but also, possibly, more creepy) maps, like this map of my walk to Birchwood with Oliver this morning:

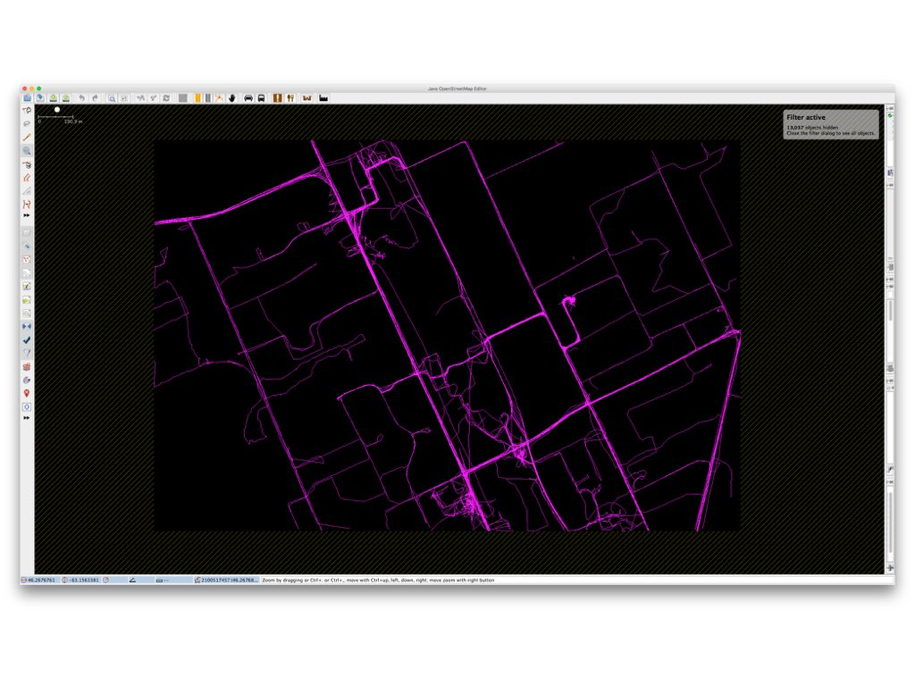

With the notion of “meaningful breadcrumbs” established, I then asked the students if they could identify this:

When they couldn’t guess, I added a hint:

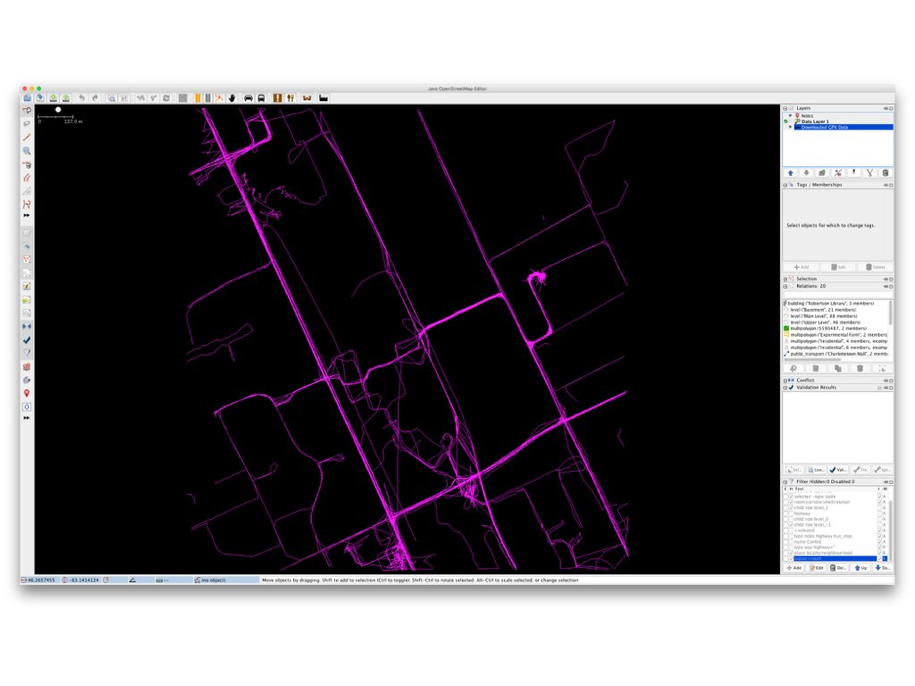

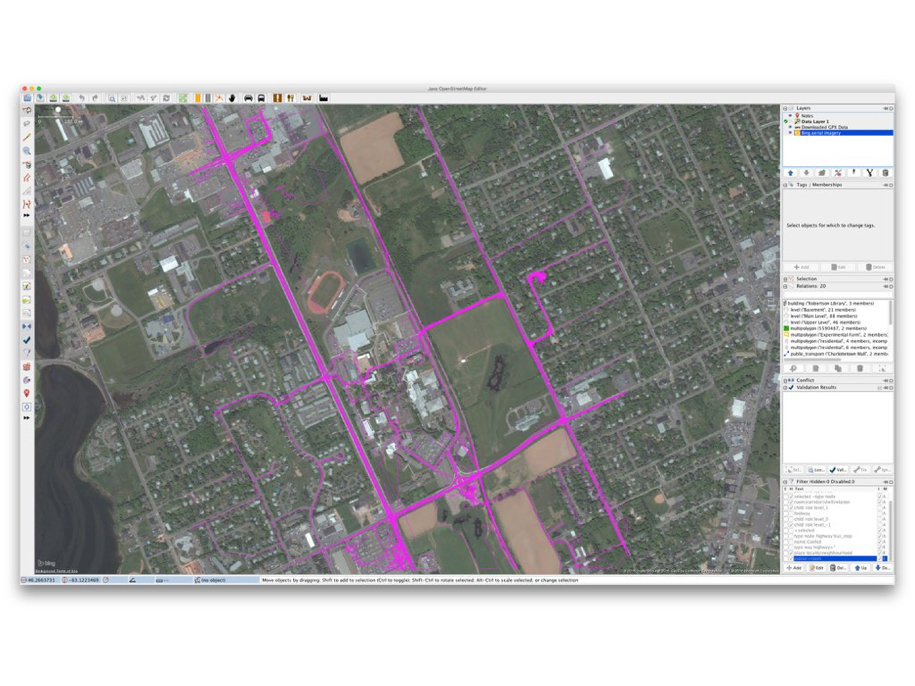

The running track was the clue that was needed to identify the location as the University of PEI itself, and I explain that the purple traces were the collected GPS traces of OpenStreetMap contributors, traces that, in enough volume like this, carve a sort of de facto map of the city.

Next, to introduce OpenStreetMap, I showed an introduction to the project by its founder Steve Coast:

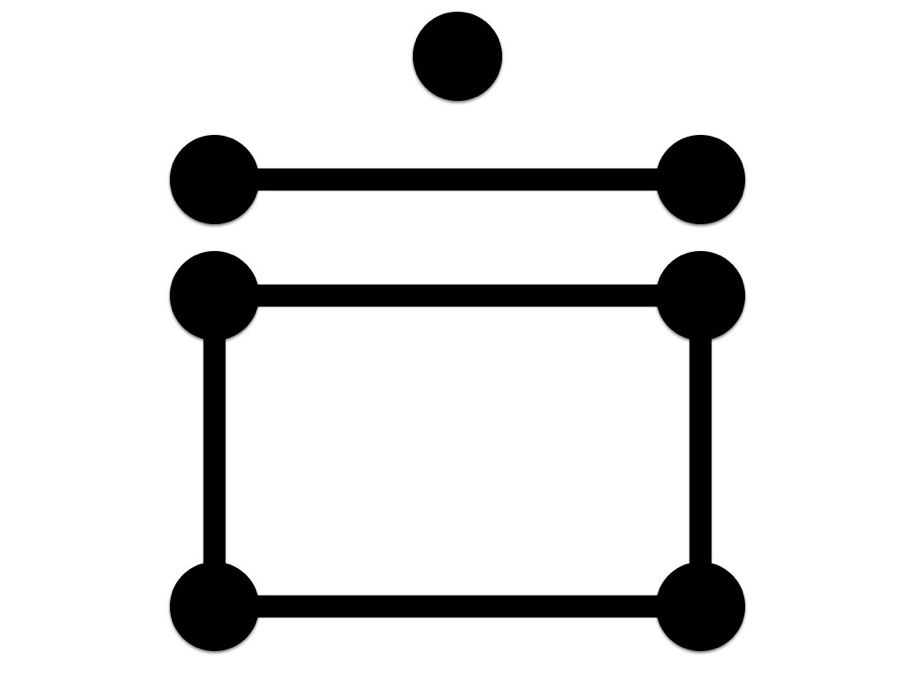

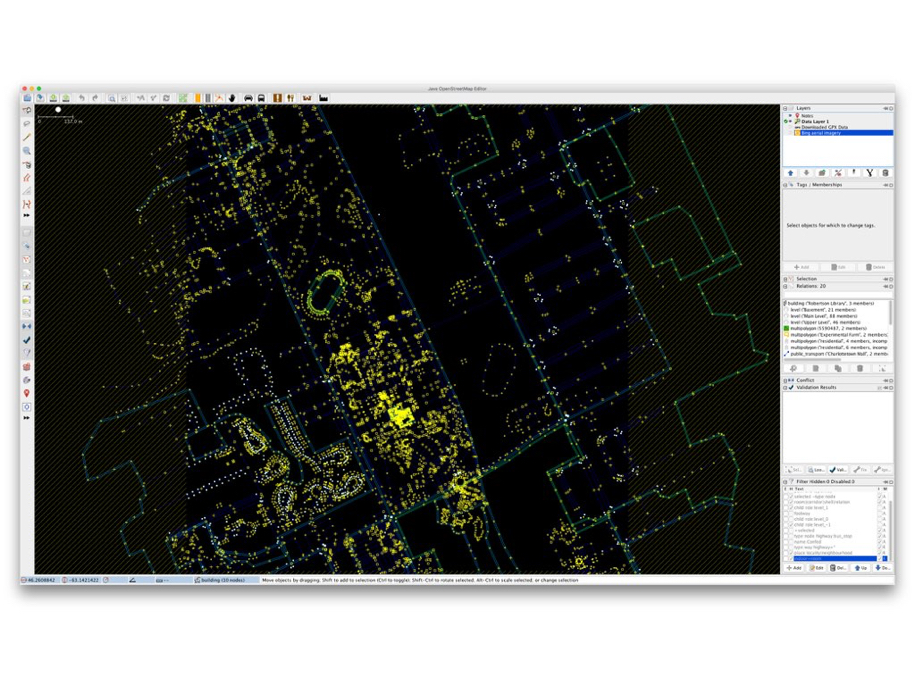

By way of introducing the underlying technical philosophy of OpenStreetMap, I discussed how, at its core, it’s about points, lines and areas, like this:

Using those primitive elements, OpenStreetMap allows these GPS traces:

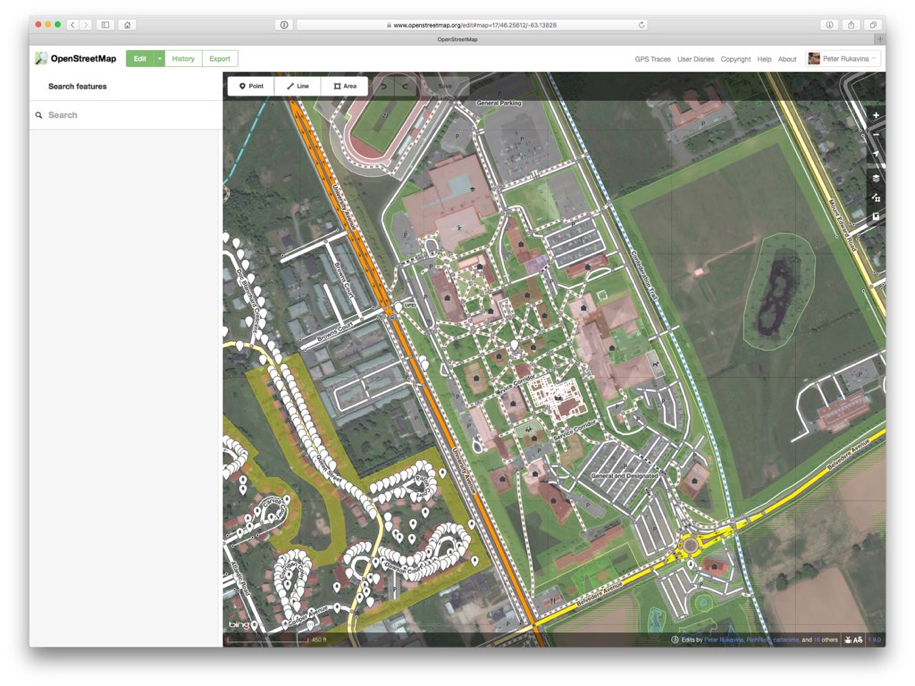

combined with satellite maps with a license that allows for tracing:

to be used to create features, and then to tag those features with metadata – this is a road, this is a path, this is a building, etc. – to create the raw materials for a map:

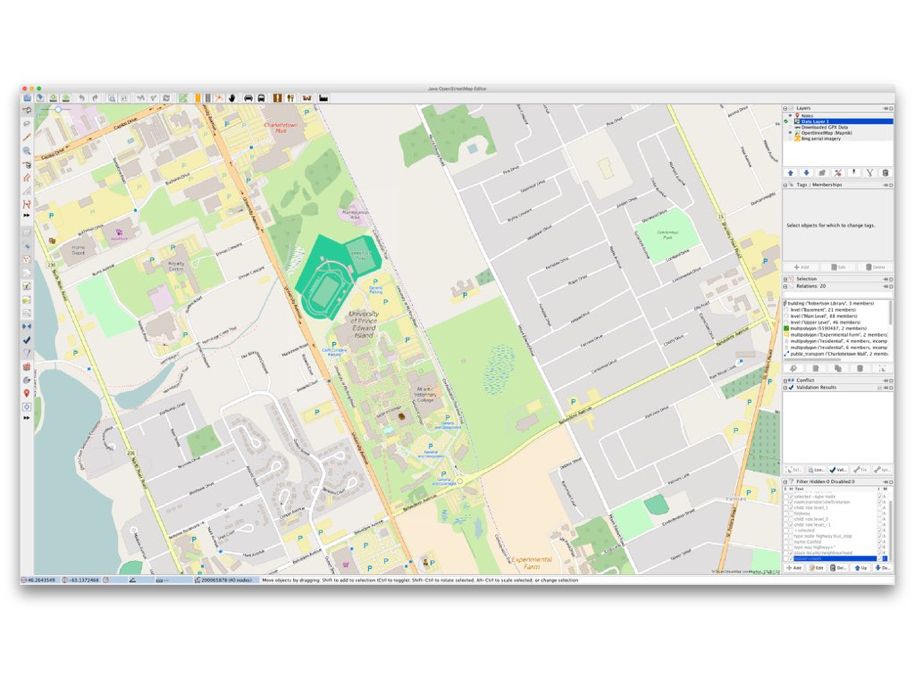

A map that, when a set of rendering rules are applied to it – make residential roads white, major roads orange, grass green, etc. – results in a human-readable map like this:

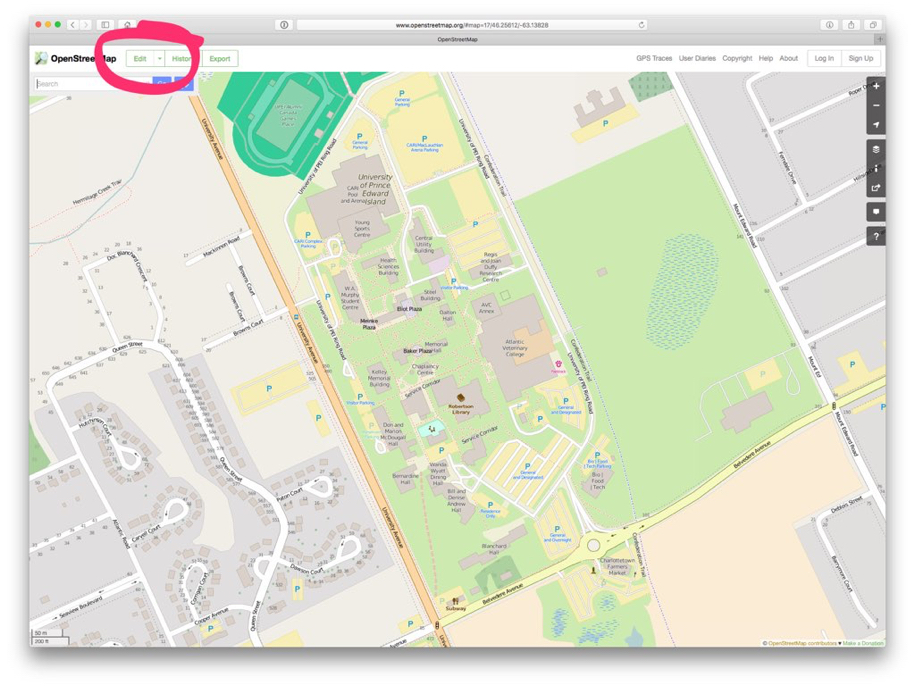

And that this is something that can be done not only with purpose-built standalone software, but in a web browser, by anyone, just by clicking “Edit”:

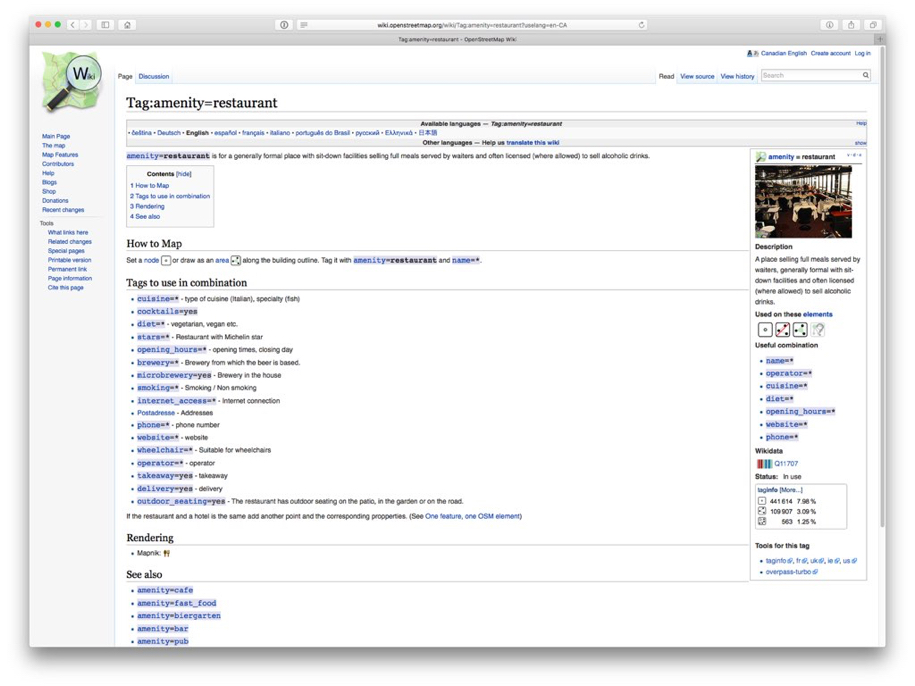

I demonstrated how the map itself a collaborative, open project, but also how the standards that drive them map – how to tag a coffee shop, how to identify a bicycle path – are developed collaboratively and in the open too, in the OpenStreetMap wiki:

With this basic understanding of the mechanics of OpenStreetMap in place, I showed the OpenStreetMap 10th Anniversary visualization video to give them a sense of the scale of the mapping community:

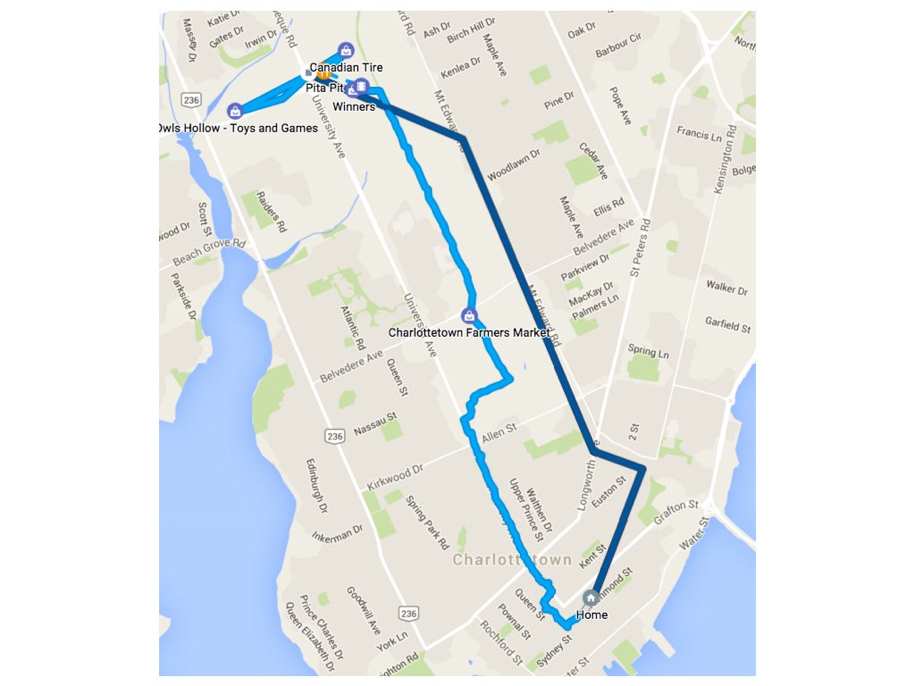

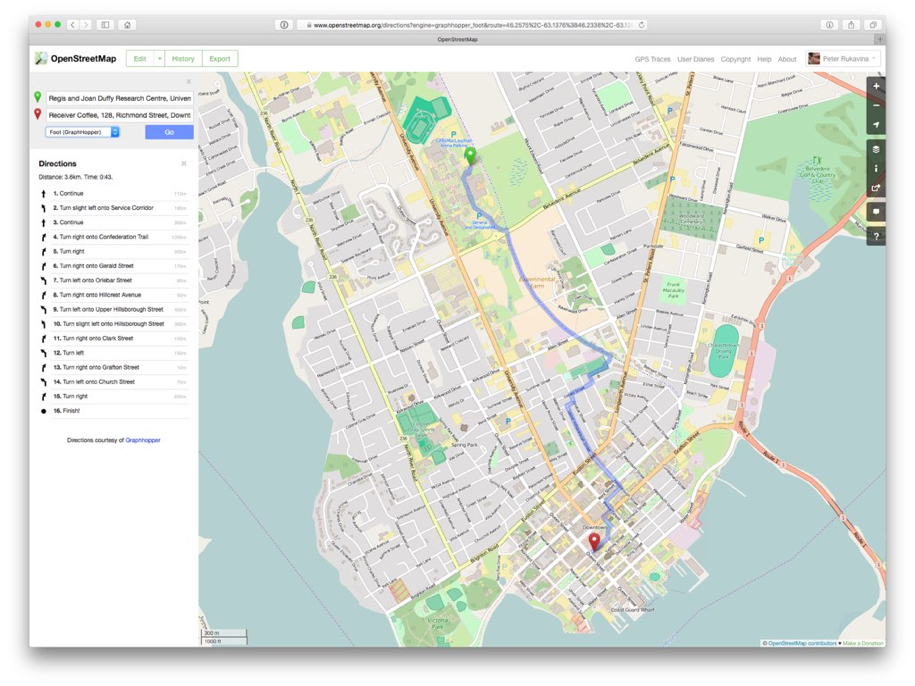

To illustrate that the project isn’t just about making slippy maps for the browser that all look the same, I showed them some examples of different manifestations of OpenStreetMap data, like walking directions:

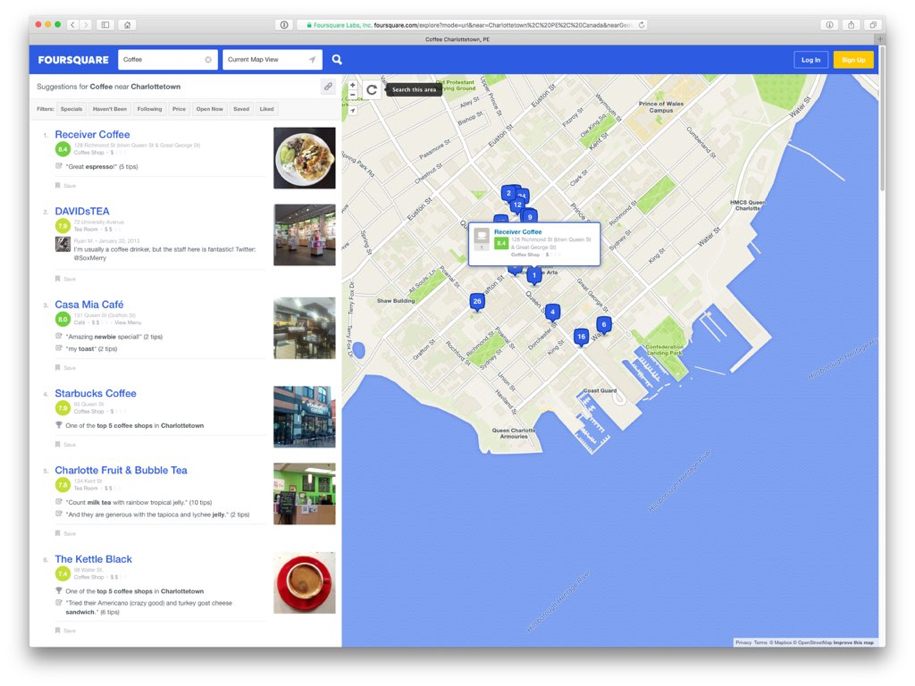

And commercial use of the map data by Foursquare:

Baby Onesie’s imprinted with the map area of your choice:

And the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team:

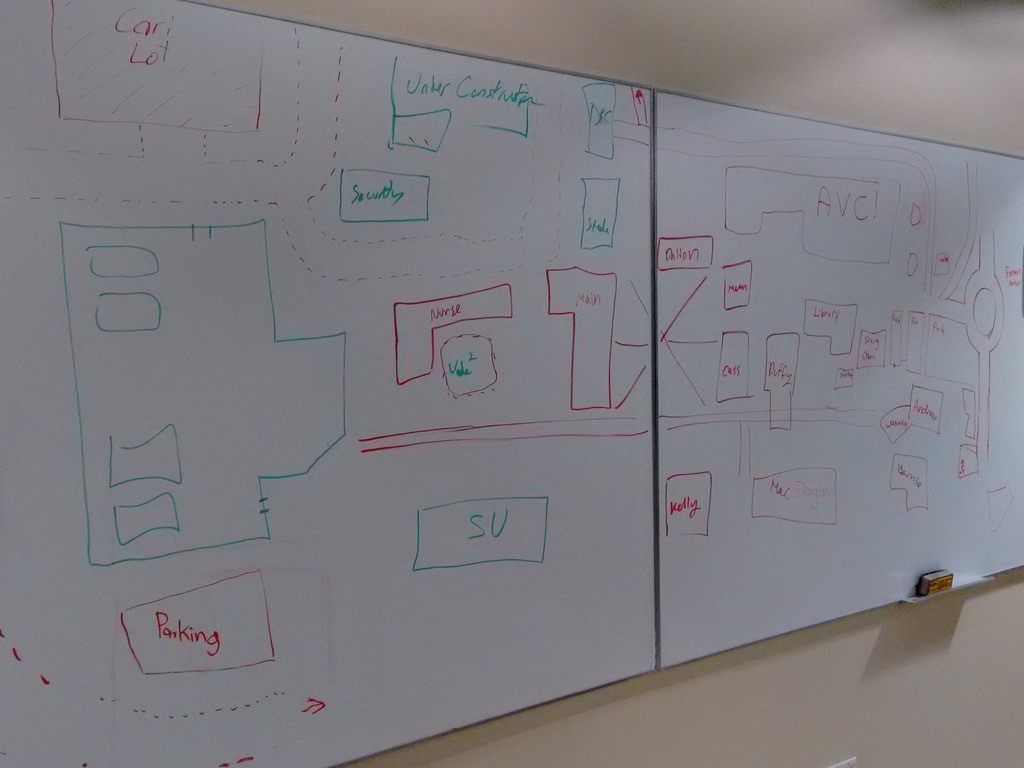

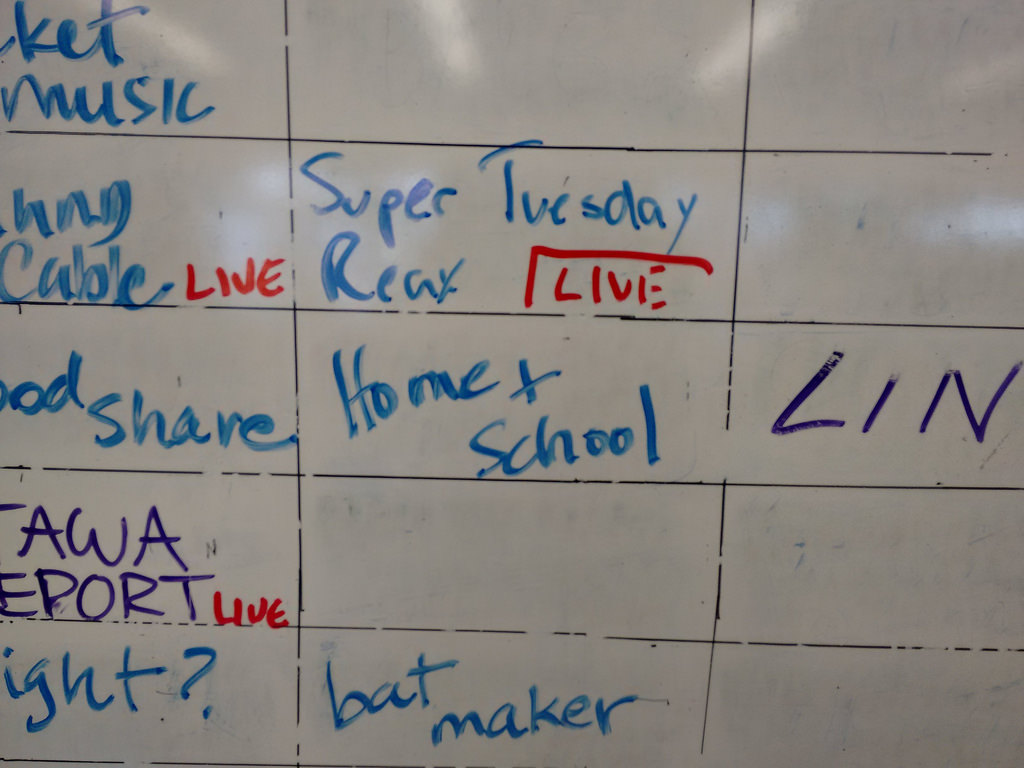

As a final exercise, with all of the above in mind, I asked them to return to the challenge of mapping the University of PEI campus, but this time as a collaborative project, using the whiteboard and the markers I’d given them at the start of the first lecture a week ago:

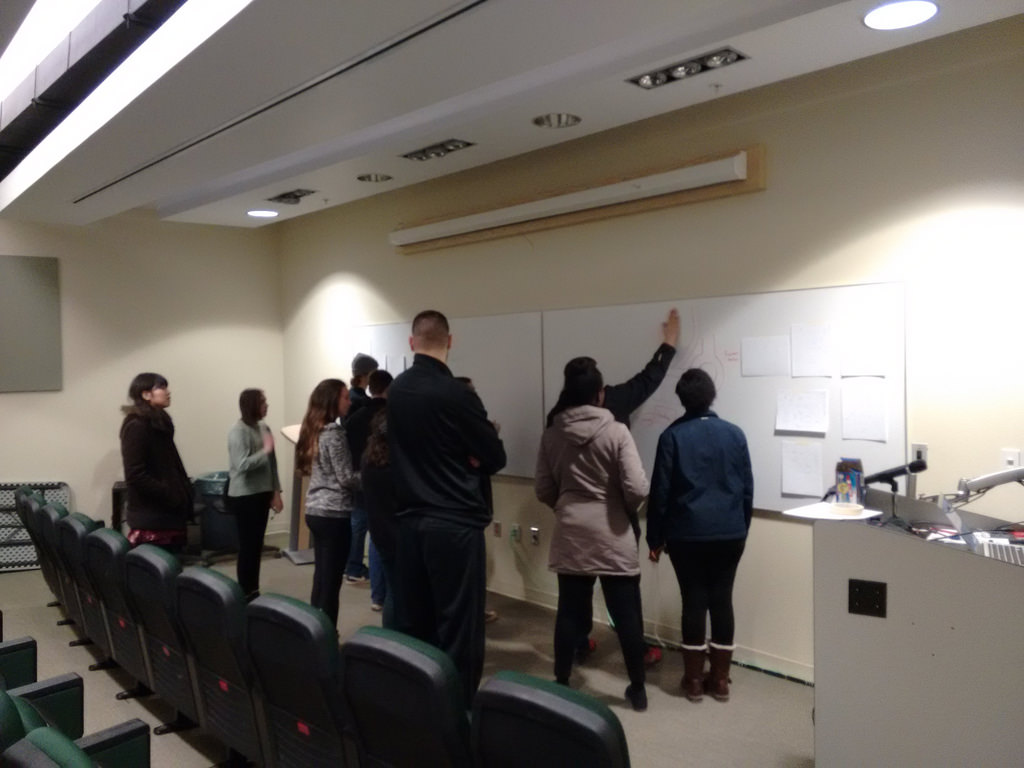

They gamely rose to this challenge:

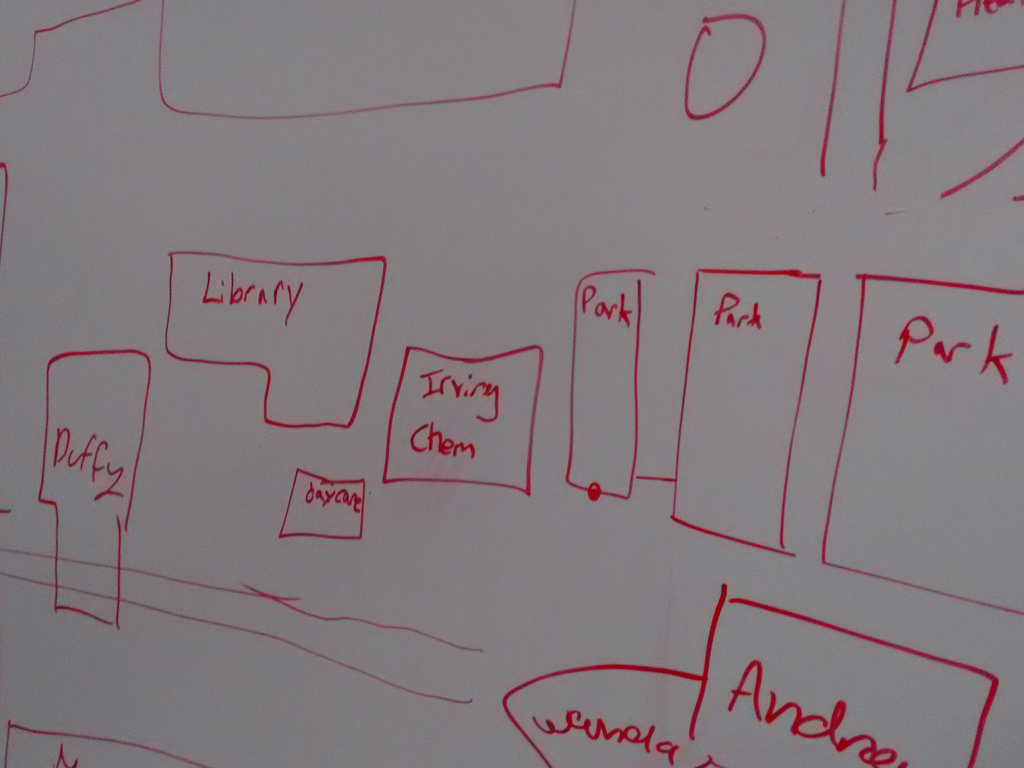

Some students held back – it was a cramped area to work together in, especially for students not used to doing so – but two groups emerged naturally that worked together on opposite ends of the campus. They achieved a surprising amount of detail and accuracy for a 10 minute whiteboard exercise:

As a final effort to knit four lectures and a lot of seemingly disconnected material together, I talked about how what united the notions of “university as a technology,” open data and open mapping was the idea of agency: agency as an actor in their education, agency over developing shared conceptions of the physical world through maps, agency over the data about them and from them that is used to shape policy.

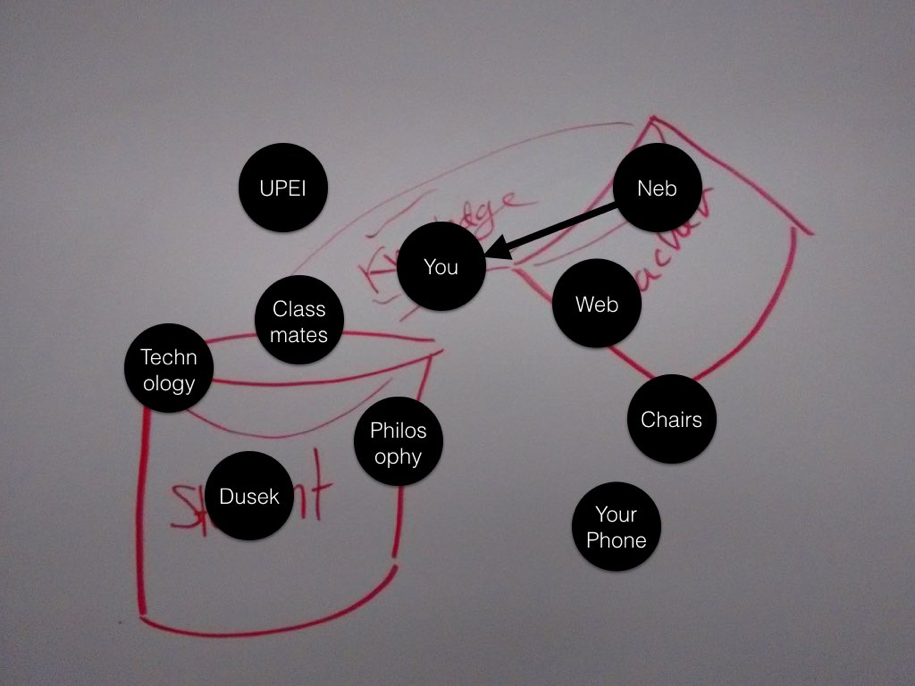

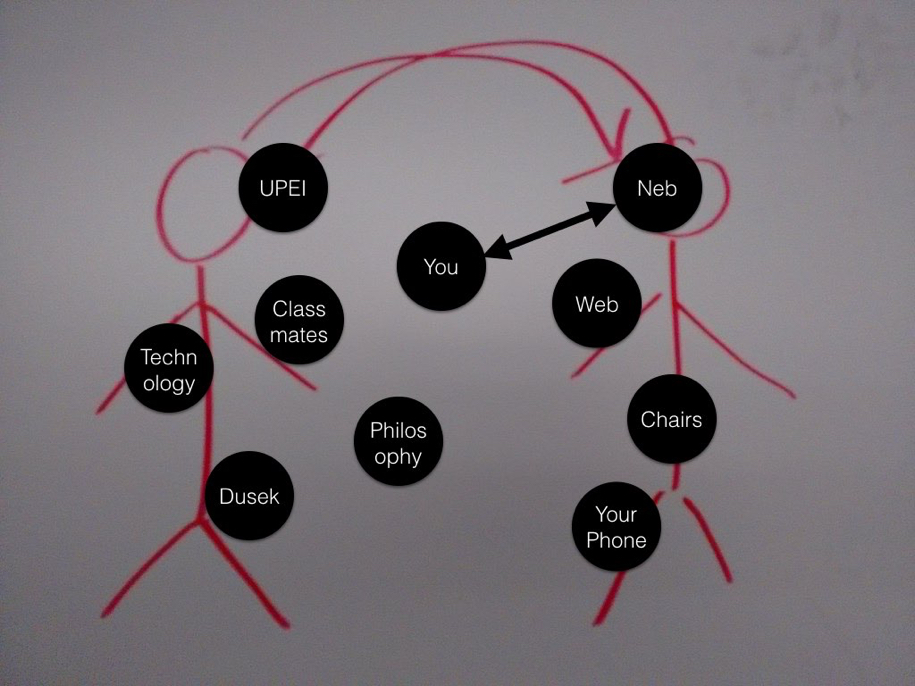

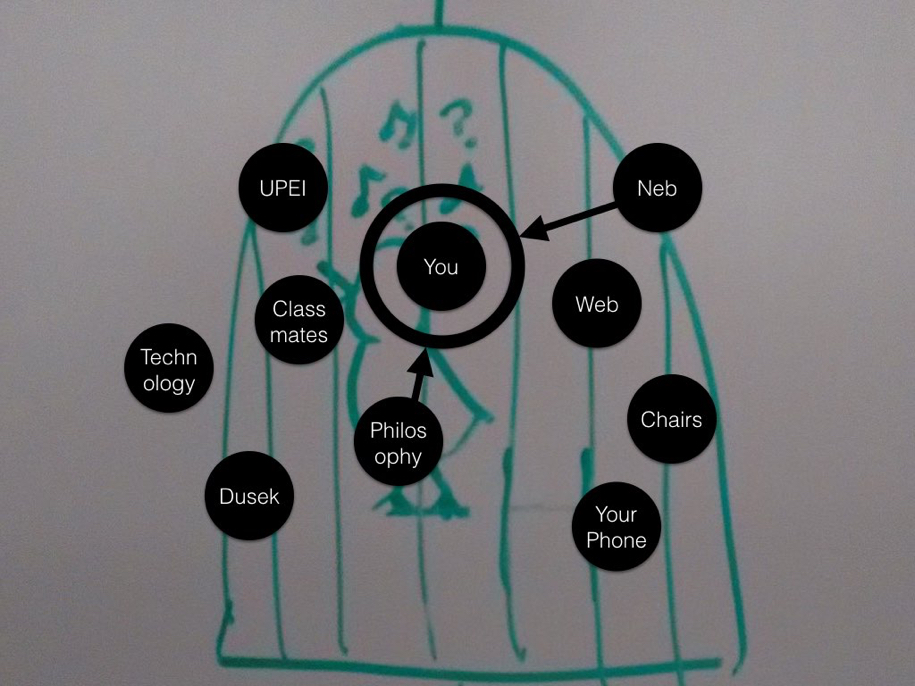

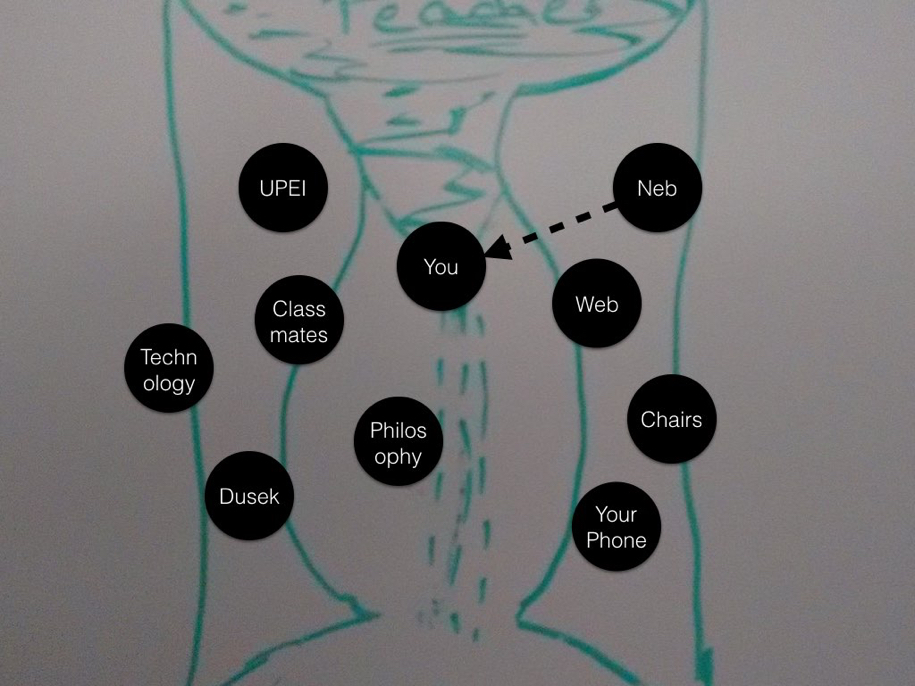

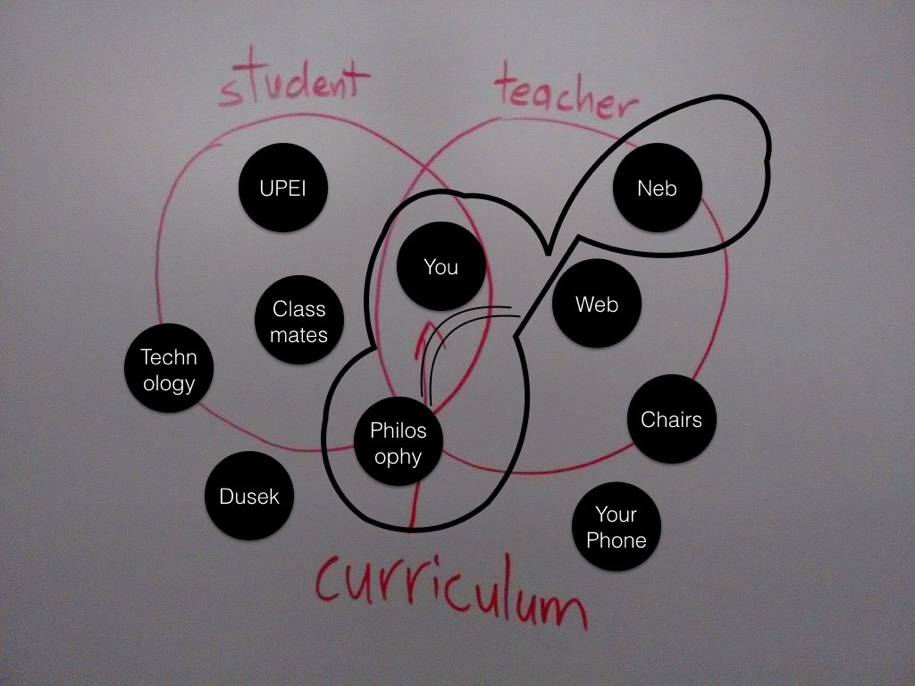

I referred back to the visualization of their own university education to date that I’d asked them to prepare in my first lecture by way of talking about different models – different conceptions of agency – in their education:

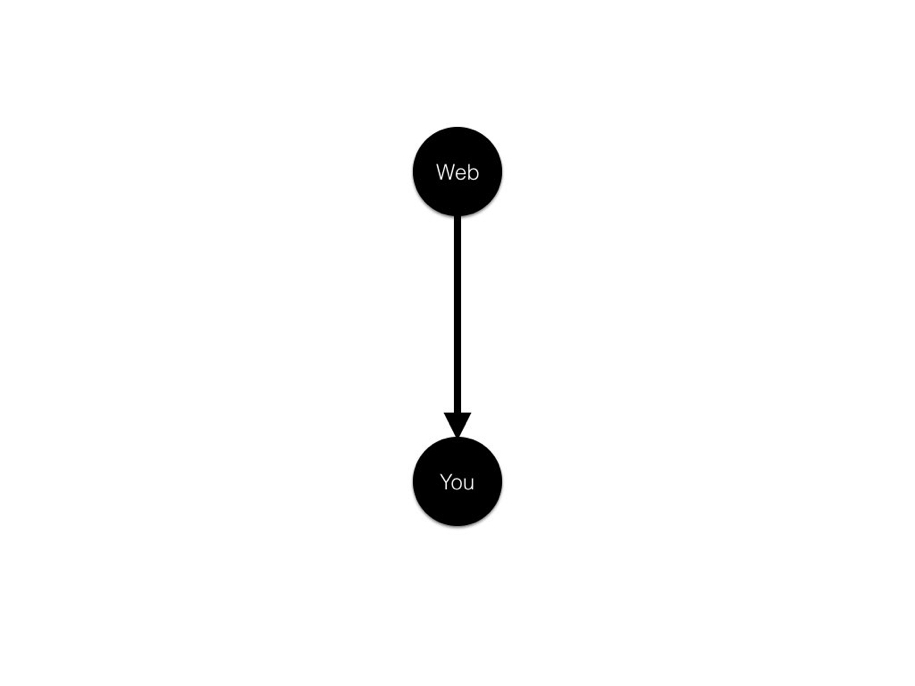

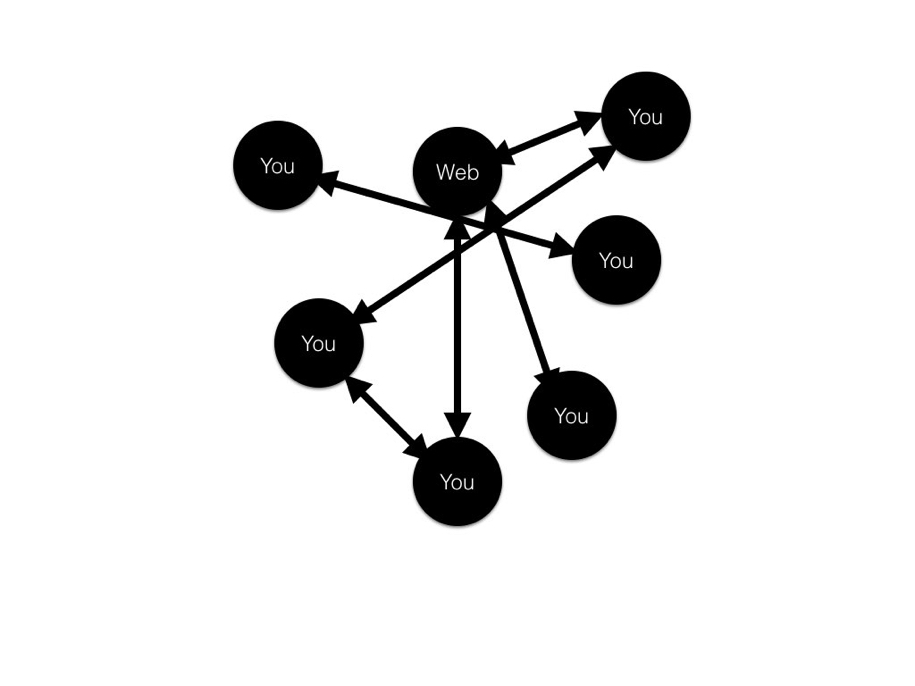

I illustrated several models of the relationship of the individual actor to the web. As a consumer:

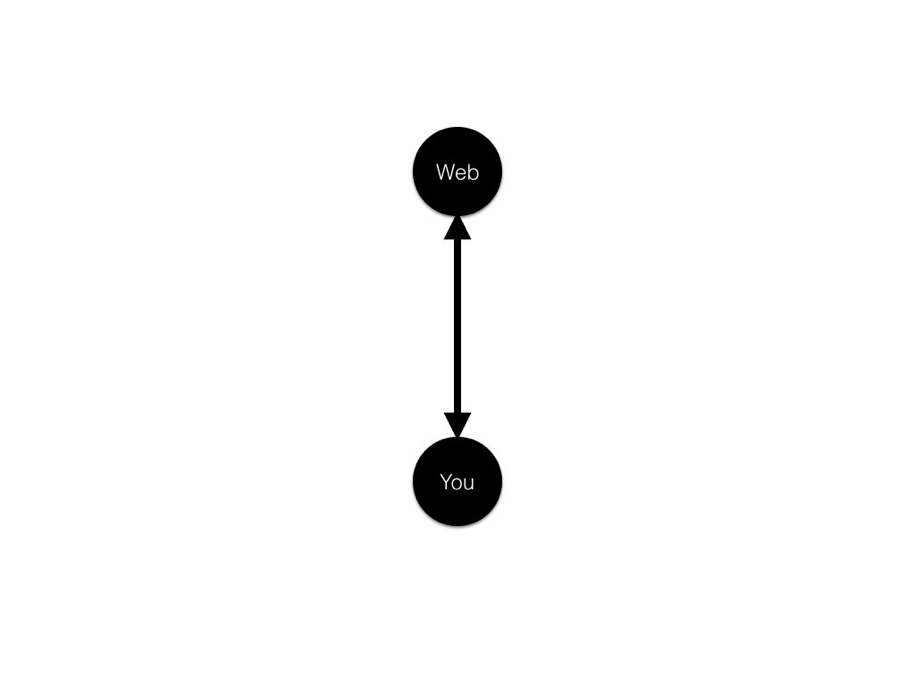

Consumer of and contributor:

And, perhaps most accurately, consumer of, contributor to, collaborator around, conduit through, as actor in a complex system that they are affecting and that is affecting them:

And with that, we were done.

I asked the students if they had any feedback on our time together, and they said I was welcome back, which was about as high a compliment as I can imagine. I asked them for a class picture, and they generously obliged:

I’ll likely have more to write about this experience in a university classroom once I’ve had a chance to ruminate on it for a while. I do come away with both a renewed appreciate for the challenges of the teaching profession but also an awareness that, when a plan comes together and learning is oozing out of the room, there is no better high.

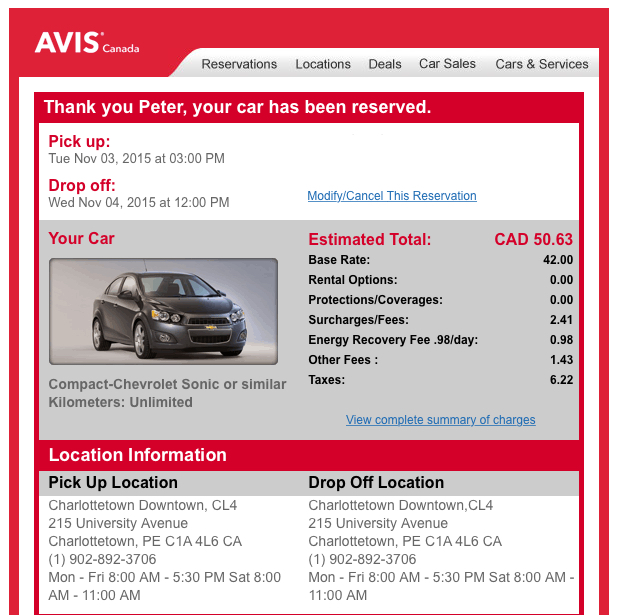

As our 2000 VW Jetta enters its later years, it’s become our habit, when driving off the Island, to rent a car. In the off-season this is always surprisingly inexpensive, a certainly much less expensive than, say, the cost of picking up the engine that’s unexpectedly fallen out of the Jetta in the Cobequid Pass.

Renting a car in downtown Charlottetown has always been easy because the Avis-Budget location is just a few blocks away from both my home and my office, so it’s been easy to walk to pick up the car (once I left the office at 4:50, reserved a car from my mobile phone while walking to pick it up, and arrived just a minute before their office closed for the day).

I was dismayed, then, to see the downtown Charlottetown Avis-Budget location at the corner of Grafton and University close down; I was afraid I’d have to resort to taking a cab out to the airport to pick up a car (or at least to walking out the Avenue to Enterprise).

It turns out, though, that Avis and Budget haven’t moved out of downtown Charlottetown, they just moved offices: their new location is at 6 Prince Street, inside Founders’ Hall, a location that happens to be even closer to our house.

So we’re back in action. Now we just need somewhere to go.

For yesterday’s session of Philosophy 105 – the third of four I’m facilitating this winter – I wanted to bring my longtime friend and colleague Ton Zijlstra into the classroom to broaden our discussion of open data.

I’d introduced the topic last week with an exploration of a local wind energy data project I’d undertaken; Ton has thought longer and harder about the fundamentals of open data, and has worked broadly in Europe with politicians and bureaucrats on the topic, and I knew it would be valuable for the students to hear from him (and I was curious to check in too!).

One of the frustrating realities of the architecture of University of Prince Edward Island classrooms – and, I imagine, most university classrooms anywhere – is that they were built with a particular “professor at the front, talking behind a podium or in front of the whiteboard” model of education in mind. While there’s been a lot of work in recent years to extend this into the digital realm – all classrooms, it seems, have a screen projector and a PC and perhaps some sort of audio-visual system – the classrooms don’t have cameras, for example, making it hard to include others in the conversation by Skype. To say nothing of being difficult to use when students aren’t sitting down and the professor isn’t speaking at them. They are not, in other words, laboratories for collaboration.

I set out to solve that issue, in an ad hoc fashion, for Monday’s session, to enable Ton to drop into the classroom.

To start, I purchased a Logitech C930E wide-angle webcam (discussed in more detail here): the camera has a 90 degree field of view (in other words, its “eye” can take in 90 degrees of space in front of it), making it well-suited to capturing a wide swath of the classroom.

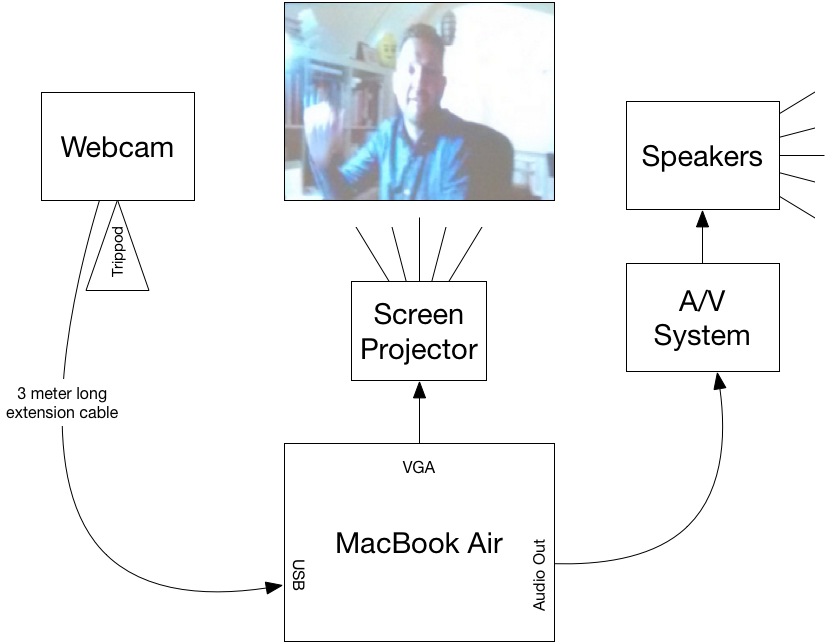

Here’s how I wired everything together:

The webcam connected to my MacBook Air by USB. It worked both as a camera, mounted on a tripod, pointing back at the classroom, but also as a microphone, picking up both my voice and the students’ (it appeared to work very well for this, and there were no problems with Ton hearing us). I used a 3 m extension cord to extend the range of the webcam, but turned out not to need it because I ended up positioning the camera on an angle to avoid having the light from the bright screen projector interfere with it.

For audio out in the classroom I connected the male 3.5 mm audio cable that emerged from the classroom’s A/V cabinet into the audio out port of my Mac and then adjusted the volume on the podium controls (it was turned down all the way when I started, which made me think it wasn’t working, but it was). The speaker system in the classroom was excellent, and everyone could hear well.

To project my MacBook Air’s screen – and Ton – onto the screen in the classroom, I connected the male VGA cable in the podium to a Thunderbolt-to-VGA adapter plugged into my computer. The Dell screen projector in the classroom automatically detected the signal and there was, unusually for such situations, no need to fiddle around with this: it just worked.

When it was all set up and running, it looked like this:

You can see the podium on the right, with the webcam on the tripod in front of it. The webcam was about 1.5 m in front of the front row of the seating and it took in everyone you can see in the photo in its view, meaning that Ton could see me (in the front row) and all the students.

Skype worked well, relatively speaking. Over 45 minutes of talking with Ton there were 3 or 4 times when audio and/or video dropped out, generally only for 10 to 15 seconds. We never lost the connection completely; it always recovered on its own. Otherwise it was like Ton was right next door: we could see and hear him, he could see and hear us, and we could forget about the technology and just have a chat.

On the way to work this morning I called into CBC Island Morning’s post-show-on-Tuesday community call-in to encourage PEI Home and School Federation member associations to use their March meetings to discuss provincial policy resolutions. When I arrived at the office an hour later, after a meeting, there was an email from personable Island Morning host Matt Rainnie asking me if I’d be able to come into the studio to tape a full-on interview about the topic. I quickly agreed, as I’m always eager to talk about home and school, and I’ve a deep belief in the power of our policy resolutions process.

Time was of the essence, so an hour later I was on the bus to the nearby CBC Prince Edward Island studios, and 15 minutes later I was sitting in the radio studio in front of a microphone:

Usually at this point in the being-interviewed-on-the-radio process I’m terrified enough of what’s to come – what if I lose my mind? what if I forget how to speak? what if I call the Premier an idiot by mistake? – that I’ve little time for anything other than worry.

But in this case I was well-versed in the material, and I had a few spare minutes to gather myself as Matt stepped out to grab me a glass of water and to fetch Richie Bolger to run the board. So I had a chance to snap a couple of “behind the mic” pictures.

Here, for example, is what Matt and Mitch see when they’re looking at Richie (except that Richie would be there, behind the glass):

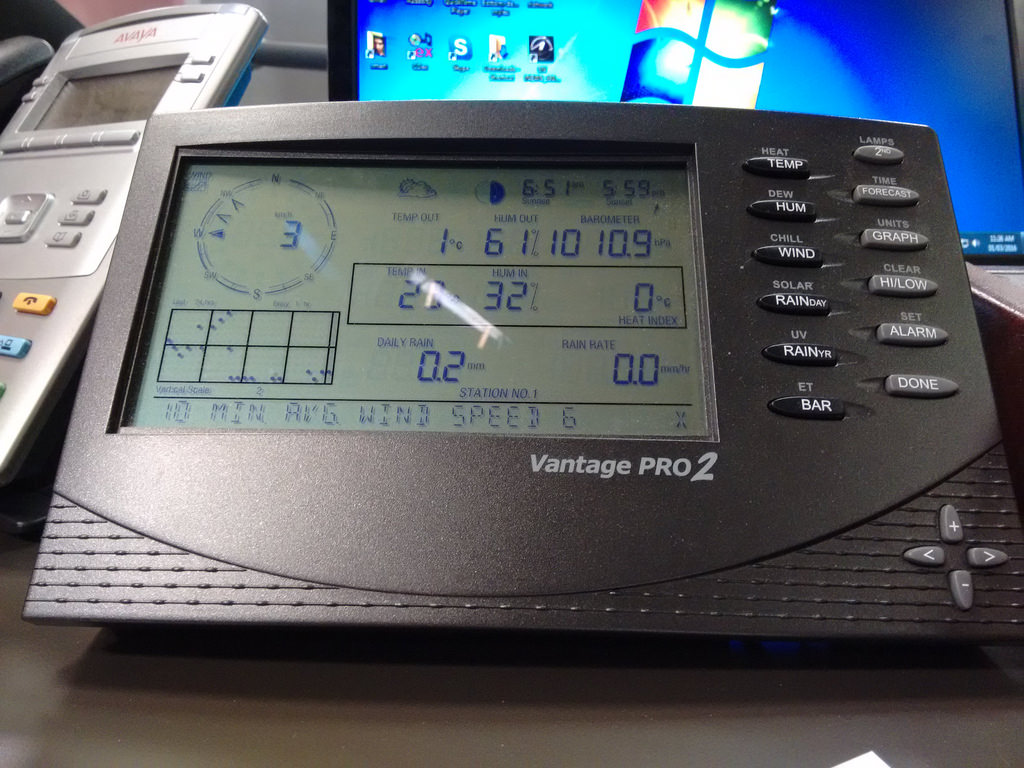

Here’s the display that Mitch and Matt consult when they want to give up to the minute weather conditions from their Vantage Pro 2 weather station:

And here’s just a couple of the multiple cameras that facilitate the live broadcast of the show on CBC Television:

The interview went well, I think – I didn’t lose my mind, forget how to speak, or mistakenly call the Premier an idiot – and on my way out the door I snapped a photo of the rundown whiteboard in the bullpen where the segment was tentatively slotted for tomorrow morning after 7:00 a.m., right after “Super Tuesday Reax” and before “Bat Maker”:

Do tune in, why don’t you!

To help me help them, the folks at T3 Transit generously gave me a monthly pass for March. So I’m living the transit high life for the month.

Among other things, it’s an opportunity for me study a la carte vs. all you can eat transit: I’ll be interested to see how not having to worry about coming up with $2.25 (or a ticket) changes the way I ride the bus.

My friends Noosh and Gina, owners of Casa Mia Café, having been planning a nighttime dessert offering for more than a year now, slowly and deliberately.

They’ve worked hard to come up with an array of house-made desserts, have held several taste-testing dry runs (causing me to temporarily suspend my sugar-free lifestyle) and now they’re ready to launch.

So this Friday and Saturday you can go to Casa Mia after dark and have what I promise you will be a excellent dessert – between Oliver and I, we’ve tasted almost all of them! – and a coffee, tea or hot chocolate.

Tell them I sent you.

I came across an ad in The New Yorker for a book called spark joy, an extended rumination on tidying. In the introduction the author summarizes her philosophy:

If you are confident that something brings you joy, keep it, regardless of what anyone else might say. Even if it isn’t perfect, no matter how mundane it might be, when you use it with care and respect, you transform it into something priceless. As you repeat this selection process, you increase your sensitivity to joy.

I thought of this today when looking for something in my filing cabinet: I came across a file folder labeled “Eatons Account” containing statements for an Eatons store credit card I had during the chain’s brief resurrection, under Sears’ ownership, in 2000.

The credit card stopped working when Sears shut down Eatons in 2002, and so the file folder contains 14 year old statements that I haven’t consulted since then.

Not only does the file folder not “spark joy” in me now, it didn’t back then (although that epic aubergine commercial the relaunched Eatons aired admittedly did).

I suspect that 95% of the stuff in my office and home falls into a similar category: kept around by its own inertia or by a vague promise of eventual usefulness (what if I want to find out how much that coat cost me at Eatons!?).

Given that it’s essentially spring outside, it might be time for some serious spring tidying.

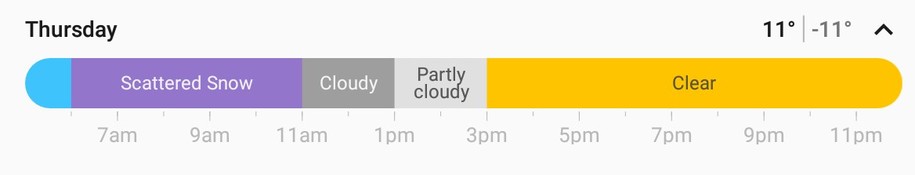

Thursday is shaping up to be an interesting weather day.

A low of temperature of -11°C and a high temperature of 11°C (it doesn’t get much better than that if you like things like that).

And every single weather condition in my weather app (the excellent Forecaster for Android): rain, snow, cloudy, partly cloudy and clear.

I bought myself a Logitech C930E USB webcam yesterday at Best Buy; my friend and colleague Ton Zijlstra is joining my Philosophy 105 class tomorrow via Skype, and I needed a way for him to be able to see the classroom and its students that was better than the built-in webcam on my MacBook Air, which has a field of view of only 38 degrees.

The C930E has a field of view of 90 degrees, and, because it’s an external camera, I can move it into the best position, mount it on a tripod (it has a built-in tripod mount) and hook it up to my Mac with a long USB extension cable.

I’ve been testing the camera for the last 24 hours to get used to it, and this has resulted in some interesting still photos (taken using the Photo Booth app that comes with every Mac).

First, this photo of [[Oliver]] and I taken yesterday afternoon in our living room.

I hung the webcam from the top of the curtains at the front of the room. Oliver’s standing on a footstool, which is why he seems so much taller than I am. You can see [[Ethan]] in the background skulking away before he’s called to appear in the photo. And, most importantly, you can see almost our entire living room and dining room. The photo weirds me out every time I look at it because it’s a view I never see otherwise (both because it’s from an unusual perspective, and also because when Oliver and I are in photos together it’s either because [[Catherine]] has taken them, or they are close-range selfies).

Here in the office, this afternoon, I moved the camera, on a tripod, as far from my desk as possible, in front of the window looking back, and took a photo of myself in front of my workstation (a MacBook Air connected to an Apple Cinema Display on a Humanscale M8 monitor arm. You get a good sense from this photo of the digital (left) and analog (right) sides of the Reinventorium. Computers on the left; metal type on the right.

I sent someone an email about ergonomics this week and in it I wrote, in part:

I highly recommend seeking outside support, especially regarding more general workstation-setup issues, as it’s almost impossible to diagnose and solve these yourself, mostly because you can’t see yourself working.

It turns out that, with an external webcam like this, that isn’t entirely true.

For example, here’s two photos a snapped with the camera a little closer to my workstation.

In the first one I realized (because I’d overcome the problem of not being able to see myself working) that I’m craning my neck a couple of inches forward when I’m working in my “natural” position:

If I adjust my posture slightly, and stack my head on top of my spine, I immediately notice a relief of pressure in my typing hands (because I’m not subtlety leaning on them), and a decrease of tension in my neck and shoulders:

This revelation causes me to wonder whether I should have a live view of my workstation beamed to my screen so that I’m always more conscious of my ergonomics. If I beamed it to the web, in fact, I could ask my ergonomics person to pop in every now and then for a spot check.

I’ll report back tomorrow afternoon after class as to how the webcam works in a classroom environment.

I am

I am