As the terrain we covered in Monday’s Philosophy 105 class was teaching, learning, and the “university as a technology,” I started today’s class by showing the students the 1967 National Film Board film Summerhill, a DVD copy of which, by happy chance, arrived in my mailbox yesterday after I ordered it last week, not particularly thinking of this as the venue.

The film is a brief overview of the British school of the same name, a school where student-run democracy is at the core, and living trumps formal learning.

I showed the film to emphasize the point that the way we teach and the way we learn are — or can be — under our control: if the university is a technology, it is a technology over which we have some dominion, even if we don’t realize it. Watching Summerhill was among the very few parts of my year at university that I remember in any detail: the film had a profound effect on me, and changed the way that I viewed my role as a student.

I can’t tell you much about the way the students felt about this film, because when it was over I ran head-on into one of my weaknesses as a teacher: I am no good at Socratic dialogue.

I’m not entirely sure why this is the case. It might be simply a general conversational-skills deficit. It might be an inability to feign interest. It might be that I’m not quick enough on my feet, and too uncomfortable with pregnant pauses. It may be a misunderstanding of the power relationship of Socrates to his students. It may be that Socratic dialogue isn’t all it’s cracked up to be anyway.

But it’s not my strong suit, and my post-film execution of it felt sort of like a bad date: other than a weakly ejected “how does the education at Summerhill compare the education you experienced,” the downbeat fell flat.

So we forged on, leaving the students to reflect on the film in their own quiet moments, unfettered by my Socractic fumbling. At least I didn’t prolong the agony.

For the second act, I presented, in relatively straight-out-of-the-boardroom Powerpointy fashion, a brief rumination on open data, my research interest du jour.

I led the students through a cut-down version of the “Cook’s Tour of Open Data” presentation I’ve made to everyone from Chief Electoral Officers to the Open Data Book Club, focusing on the story of PEI wind energy data and its possible uses.

I wanted to give them both a bird’s eye view of open data, and also an understanding of the importance of three of its core tenets: no copyright (I can do what I want with the data), no control (you can’t decide to give me the data or not based on what I propose to do with it) and no cost (the data must be freely available to all).

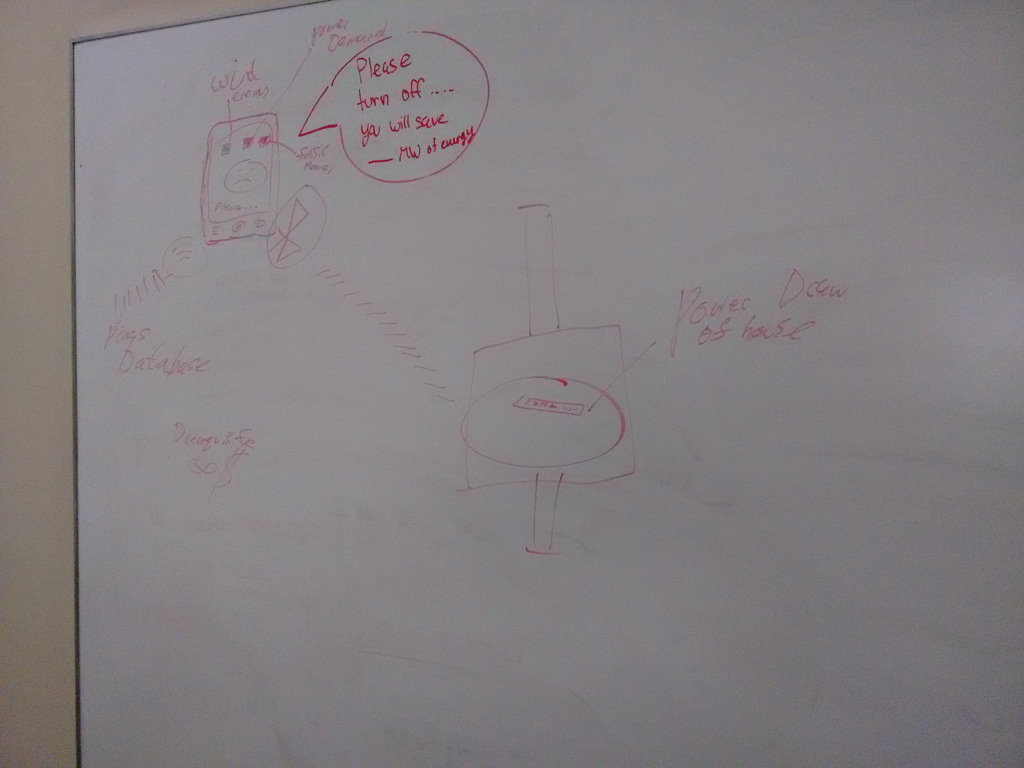

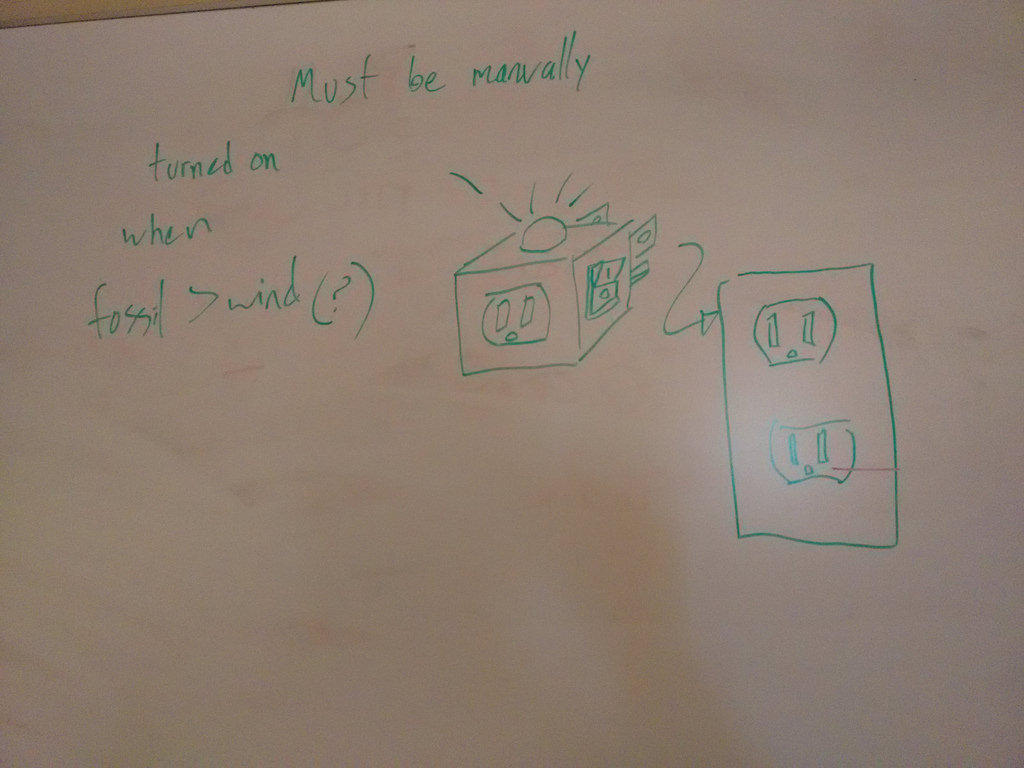

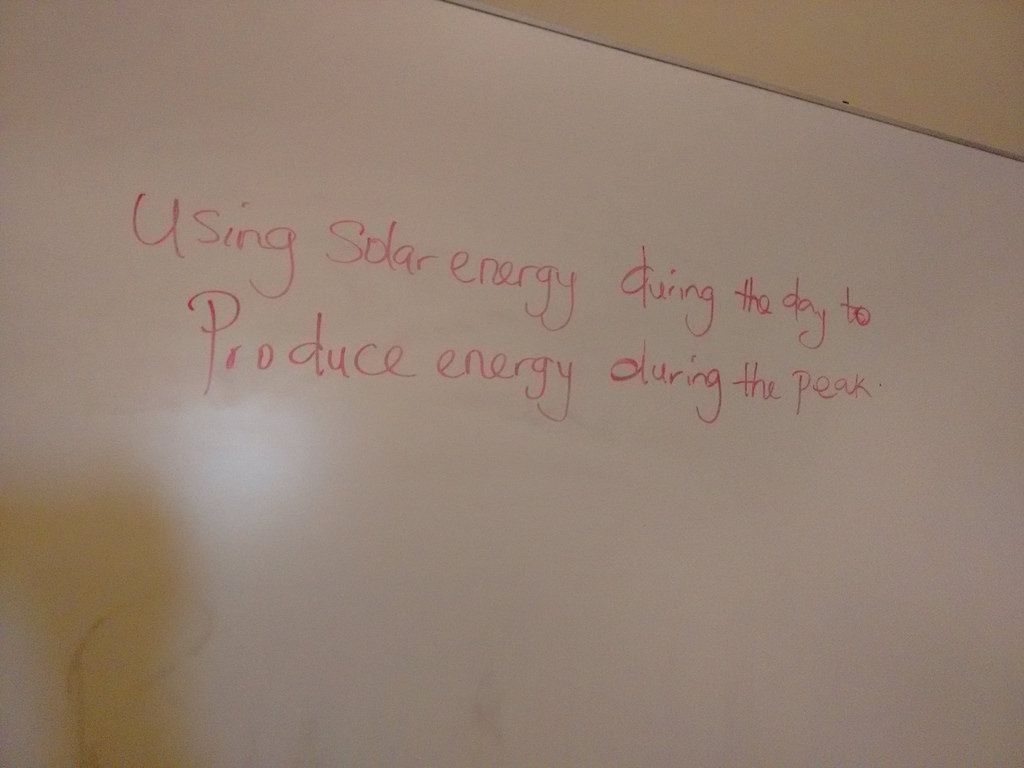

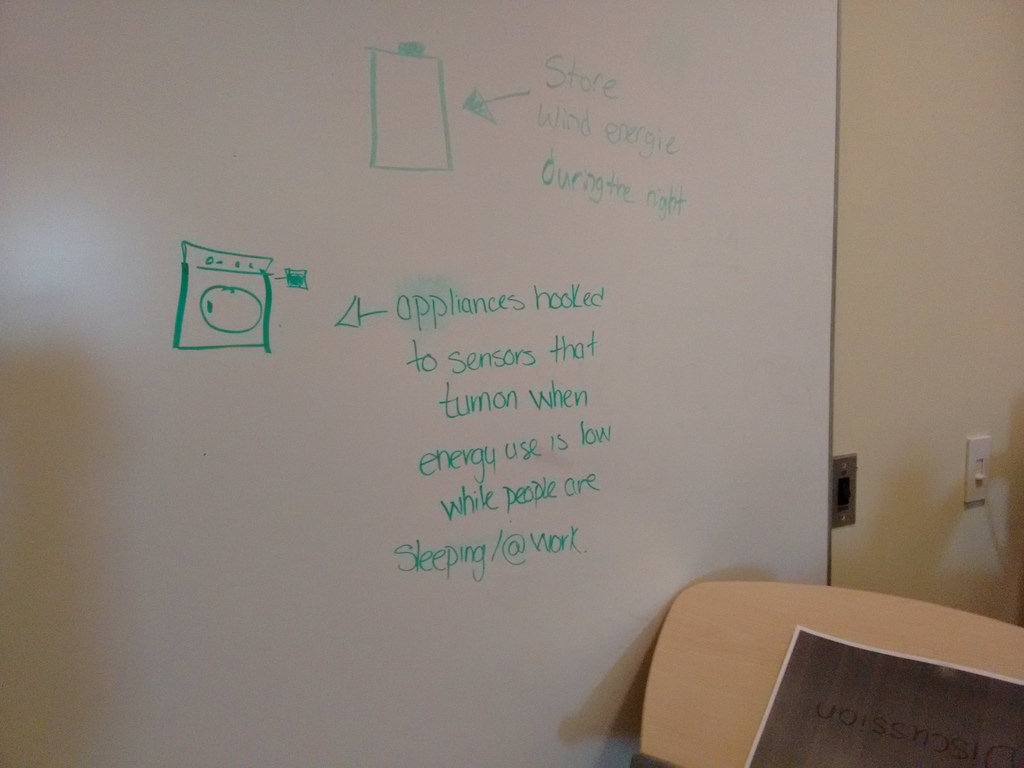

With about 30 minutes left after this introduction, I split the class into three groups — using the representations they made of their own university experiences that they drew on Monday as both a guide to likely-good colleagues and markers for them to coalesce around — and tasked them with working together to come up with a way of taking an open data set of PEI electricity data (provincial load, % from wind energy, % from local fossil fuel) and representing it to the general public in a way that would positively modify consumer behaviour (lower consumption and shift it to times when the electricity was “greener”).

After 10 minutes of discussion amongst themselves, I asked them to represent their inventions on the whiteboard, and here’s what they came up with:

Each was novel, and an impressive feat given that they developed them collaboratively in such a short time.

I finished up with a reminder that none of their inventions would be practical if they couldn’t be backstopped by open data, something that, I hope, drove home the benefits of the open data approach.

As a final exercise, on their way out the door, I asked them to take a piece of paper and drop it in one of three piles to guide me in my approach to the next two lectures: on the left was a vote for “more of Peter,” on the right was “more of Us” and in the middle was “the balance so far is pretty good.” I told them the voting was anonymous, and I did, indeed, avert my gaze while they were filing out. All but one student left their sheet in the middle “the balance so far is pretty good” pile, which I will, indeed, use to calibrate my final two classes next week.

I am

I am

Comments

I don't think I'd be very

I don't think I'd be very good at spontaneous Socratic dialog either. I'm guessing it would be a lot easier to have an idea already what you want students to take away, and the thinking steps to get there. Actually, that I'm guessing this tells me that my idea of a Socratic dialog is that the Socrates always has a specific conclusion in mind (a piece of knowledge that according to ancient Greek metaphysics you're recollecting if I'm correctly recollecting my Philosophy 101). Meanwhile, my idea of how you would like to teach, Peter, is largely the opposite. Anyway, I think you're right that it's a special kind of dialog compared to ordinary conversation, and I don't think I'd be good at it either--naturally, and prior to any experience, anyway. You might well get better at it as you go along. I tend not to thing of this myself, but it stands to reason that in some things our principal deficit might just be experience.

Add new comment