Many awesome blog posts have been lost before they were even published here because Firefox, by default, binds Command+Left Arrow to Back. Everywhere else on my Mac this key combination binds to “go to the beginning of the current line.” And I do that a lot.

What to do?

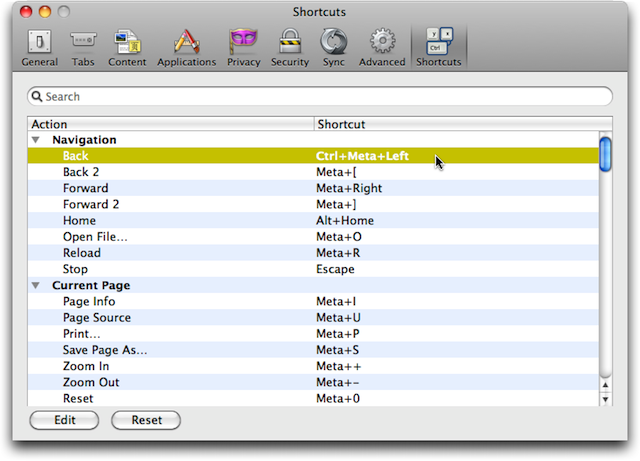

Fortunately, there’s a Firefox Add-on called Customizable Shortcuts that allows Firefox’s keyboard shortcuts to be changed, removing the dangerous implications of a casual Command+Left Arrow. Just install it and change the key combination that’s bound to Navigation | Back to something else:

Five years ago I hacked together a little system to scrape data about City of Charlottetown Building Permit Approvals from the City’s website. But when the City updated its website, the system broke and I never got around to updating it. Now I have.

- Building Permit Approval RSS Feed

- PHP code that generates the RSS Feed

- Explanation of how it all works

The RSS feed is not actually an index of approvals themselves – we’re all waiting on the City’s long-awaited system to do this – it’s simply an index that gets updated when the City releases a new PDF file. But it’s something.

I was speaking with someone last week who expressed surprise that Google Translate had done a less-than-optimal job at translating a passage of text from English to French.

I’ve spent more than my fair share of time using Google Translate over the past two weeks as my Ukrainian-speaking Cousin Sergey is here and while he’s making quick work of learning English, we fall back on machine translation for more complicated conversations.

While Google does have a useful explanation of Google Translate’s limitations – “This process of seeking patterns in large amounts of text is called ‘statistical machine translation’. Since the translations are generated by machines, not all translation will be perfect.” – this is likely an explanation that few people ever see, and so, with lack of any evidence to the contrary, I think the general assumption from the lay public is that when you type something into Google Translate in English, what you get back in Ukrainian or Persian or French is “right.”

But that’s just not true.

While these translations may be “right enough” to get a point across, especially for less ambiguous statements, you should never rely on Google Translate for translating important materials – things intended for print, legal documents, invitations to marry, etc. – as the opportunity for machine-induced error or ambiguity, to say nothing of the absence of local colour or subtlety, is high.

Remember how I was looking for a space to house and operate my newly-acquired letterpress? Well, I’m still looking. It turns out that Charlottetown, at least very-broadly-defined “downtown” Charlottetown, has very, very little surplus “light industrial” space.

So far I’ve had the kind offer to two spaces, for free, that, alas, didn’t pan out because of difficulty of access; everything else I’ve looked at has been either too expensive or too much space (I can’t spend $1000/month to feed what amounts to a equipment-intensive hobby, and I only need a couple of hundred square feet).

So, I’m calling on all of you in the local readership to plumb your networks for me to see if you can help drum something up.

(All of this makes me wonder how much creative pursuit is being held back because of real estate issues; I used to scoff at artists when they talked about the need for space: now I know just how real a challenge it is!)

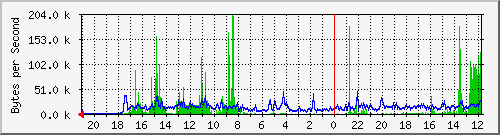

There was a 3-hour interruption in Eastlink Internet service this evening that affected service here to Reinvented HQ. So this site was offline, as was our email and telephone. Things seem to be returning to normal now, but if you were trying to reach me by email to tell me that you’d fallen into a well and needed my help, you should probably send your message again.

Today was moving day for the Golding Jobber letterpress that’s coming into town from Campbell’s Printing in Tryon. The goal for today was to get the press – in all its giganticness – from Tryon into a Queen Street basement. In the end, we made it half way.

I started the day out at the Campbell’s working with Bill to peel of the removable parts of the press – the ink disc, engine, and various other bits and bobs – and get them into my car.

At 10:30 a.m. the mover arrived and from 10:30 to just after noon they tried, really really hard, to move the press. What was originally estimated at “700 or 800 pounds” ended up being, in their estimation, about 1500 pounds of letterpress, and top-heavy at that. These guys are piano movers, and they really struggled to wrangle the press in a way that didn’t wreck the press, or themselves. In the end it was beyond the tools they had available to them, and the press had only moved from the middle of the room to the door. They apologized for not being able to go any further, I paid them for their time and gas, and off they went.

Next up was Griffin’s Towing on the Bannockburn Road. Bill and Gertie’s son works for them, and they knew that Griffin’s had serious “big stuff moving” gear. A call was made. Tea and turkey sandwiches were had.

And then, while we were waiting, Bill and Gertie and I managed to lower the behemoth from foot-high position on wooden blocks where it had been left and onto metal rollers. I don’t want to gloat, but the three of us did a pretty good job, and lived to tell the tale.

Twenty minutes later a flatbed tow truck pulled up, negotiations about position and approach ensued, and within half an hour the letterpress had been winched out the door and onto the bed of the truck and secure in place.

With new-found knowledge of the Golding’s heaviness, and given that I didn’t have a crew of skilled burly movers at the ready to help negotiate into a Queen Street basement, I happily took Griffin’s offer of leaving the press in an disused corner of their shop in Clyde River until alternate arrangements could be made.

And so we set off, tow truck and letterpress leading the convoy, me behind (and thus the victim of any freak cable snap sending 1500 pounds of Massachusetts-crafted iron through my windshield).

The first six feet cost me $100, the next 30km cost me $60 (I like the was this is trending).

Lessons learned: I know absolutely nothing about how much things weigh; you need serious kit to move 1500 pounds of iron; Griffin’s Towing is quick, efficient and super friendly and if I ever need anything big or heavy moved, they are now my go-to guys; Bill and Gertie Campbell are among the most kind, good-humored, and patient people I’ve ever met.

If you had any advice on who to turn to for moving a really heavy something into a tricky basement location, please let me know.

Hard to believe it’s been a year since the last Wayzgoose at Gaspereau Press in Kentville, Nova Scotia, but it’s coming up again this weekend. Last year Erin Bateman and I went, making a Herculean trip over and back in one day; it was a great trip, and I’m thinking of going over again this year, a trip the possibilities of which are made more interesting by Thursday and Friday being days off school for Oliver. I’ve spent a total of 6 hours in “the valley” of Nova Scotia in my life: perhaps a time to experience a little more of it?

A couple of days ago I got an email from Stephan MacLeod, one of our Zap Your PRAM Fellows, inviting me to dinner with his boss, Evan Jones.

In general I’m not the kind of guy who people invite out to dinner. Unless you’re Catherine, or one of my brothers, you’ve probably never said “hey, I should invite Peter out to dinner.” So I have little experience in this realm. But I’m always game for adventure and, heck, Evan’s bio billed him as a “two-time Emmy award winner,” so he had to be at least somewhat interesting, didn’t he?

Yesterday morning I got an email from Evan’s assistant Natalie.

In general I’m not the kind of guy who interacts with a lot of people who have assistants. Unless you’re my doctor or my dentist, it’s likely that if we communicate we do so in a disintermediated fashion. If you’re important enough to have an assistant, then you’re likely too important to talk to me. So, two Emmys and an assistant: what was I getting myself into?

I arranged with Natalie to meet Evan at Sushi Jeju at 7:00 p.m. and so, after working a little later than usual, I hopped on my bicycle and rode over. Walking in the door I suddenly realized that, what with all the Natalie-mediated communication, I’d completely forgotten what’s-his-name’s name.

(In general I’m not the kind of guy who meets a lot of new people, so my new-person-name-remembering skills have atrophied).

Fortunately I was there first, and a quick check of my inbox revealed that what’s-his-name was Evan and 30 seconds later, as I rushed to clear the evidence of my forgetfulness from the table, Evan walked in the door.

As it turns out, Evan, in addition to having an assistant and being a two-time Emmy-award winner, grew up in Copetown, Ontario. Which is about 30 minutes from where I grew up in Carlisle. He was from West Flamborough, I was from East Flamborough. We were practically brothers.

And so we had an interesting 2-hour long conversation over Indian fried rice and Sapporo beer and I learned an awful lot about an awful lot.

All of which has me thinking that I should be more actively seeking out dining opportunities with Emmy-award-winner people who have assistants. If you happen to be one of these people, please have your assistant call me and we can set something up.

Eve Goldberg, who falls into my “favourite people who I haven’t seen face to face in 25 years” category of friends, sent me an email this morning.

I met Eve in high school in Toronto where we were both budding scientists at the Ontario Science Centre. We kept in touch for a few years off, then lost touch for an awfully long time, and then a few years back I heard from her again, perhaps as a result of her instrumental Watermelon Sorbet being used as the theme song for Richardson’s Roundup on CBC Radio One.

That Eve is a professional musician and I am, well, whatever I am, and that neither of us is curing cancer nor splitting the atom1 is a testament that science is not for everyone. But I think we count ourselves lucky for our early dabbles in that world.

Anyway, Eve emailed today to tell me that she’s coming to Prince Edward Island to play three “house concert” dates on October 29, 30 and November 1 in Bedeque, Summerside and Charlottetown respectively (details).

I never knew Eve as a musician back in the day, so this side of her is all new to me – it’s sort of like learning she had a secret superpower all those years that I never knew about – and I’m quite looking forward to seeing her play.

1. In addition to her musical work it’s possible that Eve also has a sideline as a cancer-curing atom splitter.

If you’re a geonerd like me, finding a whole new level of geography somewhere is like discovering gold. When I used the parishes of Prince Edward Island as an example of the map layers available from the Province of Prince Edward Island I had no idea what I had accidentally discovered: I’d assumed these were some sort of religious slice-and-dice of the province.

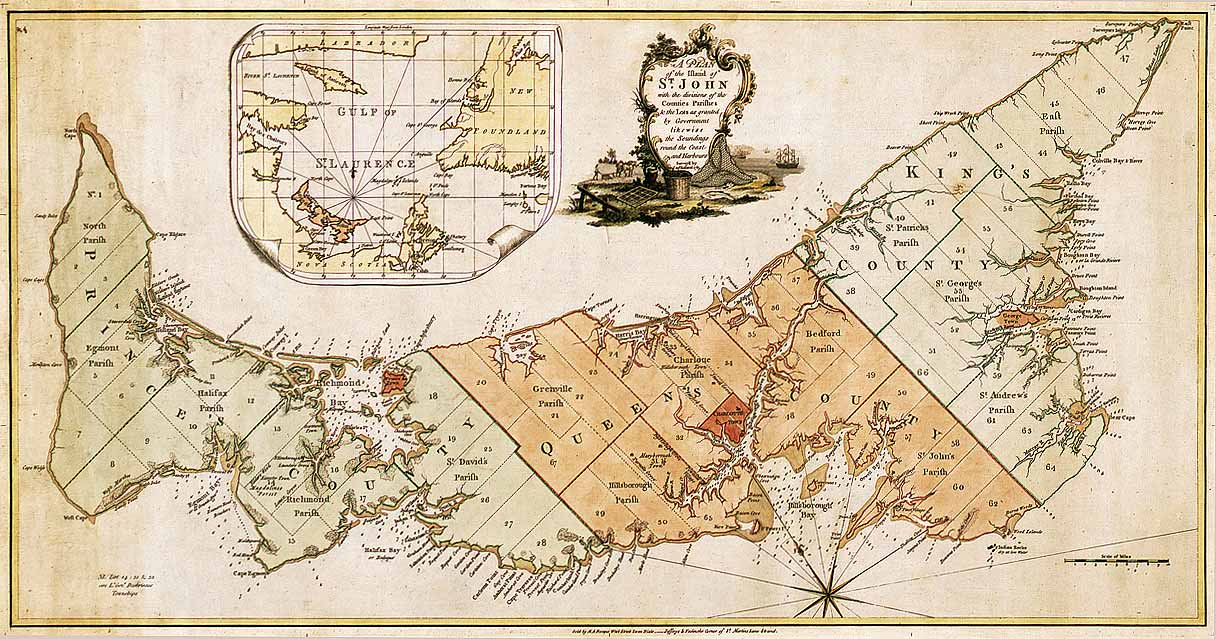

Talking to G. last night, though, I came to learn that the “parish” level of geography here on the Island goes back to Samuel Holland, the surveyor who originally laid out the “lots” system for Prince Edward Island. At the same time as he surveyed the lots he also created parishes, collections of lots, and gave each a name. Here’s a map from the National Archives that illustrates this:

And here’s a list of all the parishes, with locator maps for each. Each parish has a story behind its name – North and East are self-evident, and Wikipedia has the story behind some of the names but it would be nice to see this agglomeration get the documentation it’s due.

G. says that parish boundaries never really came into fashion in bureaucratic use; does anyone have example of situations where they were used (or still are in use)?

I am

I am