The Province of Prince Edward Island has a large collection of “free” GIS data on its website (that’s “free” as in “you can use it if you agree to our crazy license terms” not free as in “go forth and live, fair data”).

To download any of the data files is a cumbersome process that requires agreeing to license terms and then entering your name, email address and occupation. All of which makes getting all of the data rather time-consuming.

Fortunately all the files are actually there, sitting unencumbered on a webserver waiting to be downloaded, so it’s relatively easy to scrape the free GIS data file lists (here and here), extrapolate the names of the data files, and then automatically download them.

That’s what this PHP code does for you: download it, configure, let it run and shortly you’ll have a few gigabytes of GIS data – everything from school board boundaries to walking trails to soils – sitting on your local machine ready for use (the script, by default, just grabs the ESRI Shapefiles).

Given the rather violent response to making public data, well, public, that the province has shown in past, I recommend you grab your data now, before this is made more difficult and cumbersome still.

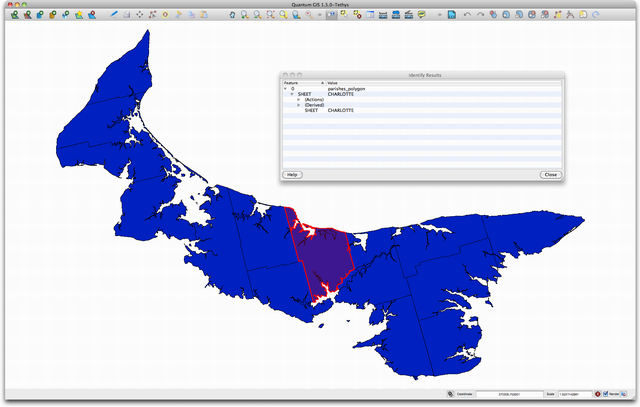

I recommend the free Quantum GIS application for manipulating the files once you have them: it reads Shapefiles natively and is quite feature-rich. Here’s a map of the parishes of Prince Edward Island inside Qgis, for example:

I had a request from the Executive Director of the PEI Home and School Federation earlier this week for a map of schools on Prince Edward Island. The Federation is putting together an “info kit” for local home and schools and wanted a map to include as a resource.

I went looking for the information in a couple of places – the province’s GIS Data Catalog, the Eastern School District and Western School Board websites, for example – but found nothing. The closest I came was the School Finder on the Department of Education’s website.

As most of the data required to make a map appeared to be buried inside the HTML of the School Finder, I set out to scrape the data out of that page and into a format suitable for mapping. The primary challenges in doing so were related to the poorly-formed HTML of the page, which made automatically pulling out certain elements more challenging, and the poorly-formed and somewhat inaccurate civic address data – addresses like “3326 Trans Canada Highway Route No 1” that conform to the Civic Addressing Standards (the proper form would be “3326 Trans Canada Hwy - Rte 1”).

But with a mixture of manual and automatic data wrangling I ended up with a CSV file of civic addresses that I could then match against freely-available civic address data to get the latitude and longitude of each school.

The result of this process was a CSV file of school locations which I then ran through the excellent KMLCSV Converter application to make a KML file of schools suitable for mapping.

You can see the result overlaid on a Google Map or overlaid on a CloudMade-powered OpenStreetMap:

My next challenge – only because I think it’s information that should be freely available – is to find GIS data for the “school zone boundaries” that indicated which kids from which neighbourhoods go to which schools. For the time being this information for the Western Board, is only available as a textual PDF file of School Attendance Zones, for the French Language School Board as a series of PDF files of “territory served” by school, and for the Eastern District has PDF maps by “family of schools” (Bluefield, Charlottetown Rural, Colonel Gray, Montague,

Morell, Souris).

As we’re inevitably going to have to take the Eastern District through a “rezoning” exercise – it’s been put off for far too long – it behooves we parents to equip ourselves with the planning tools now so that we can make meaningful contributions to the process.

We had a wonderful Thanksgiving dinner in Little Sands yesterday, packed into a very full house with a group of friends and family new and old. The house is 5 minutes walk from the beach and so after a supper of turkey and turnips and mashed potatoes and apple pie and pumpkin pie and untold other delights Oliver and Sergey and I took a walk down to the shore. We got there just as the sun was going down.

The following notice appeared on the City of Charlottetown’s website this morning:

City Council will hold a Public Meeting to hear comments on the following:

Property Adjacent to 4 Prince Street (portion of PID# 841536)

An amendment to Appendix “G” of the City of Charlottetown Zoning and Development Bylaw – List of Approved Properties in the Comprehensive

Development Area Zone and Their Permitted Uses, as well as an amendment to the Waterfront Concept Plan to allow commercial, office and residential units for the vacant lot adjacent to 4 Prince Street (PID# 841536).

This is an area I know well – I walk by on the way from my house to the Charlottetown waterfront – and have some interest in. I’m part of the public that should be involved in a public meeting like this.

But reading this notice I’m left with a lot of questions:

- Where exactly is this property? What “portion” of PID #841536 is the meeting about? A map or even a sketch of what’s being talked about would be useful here.

- What’s “Appendix G” of the Zoning and Development Bylaw? Yes, I know I can download the bylaw and figure that out, but the web, if anything, is about making connections between documents. The bylaw should be in HTML, not PDF, and there should be a link from this meeting notice directly to Appendix G.

- What is the “Comprehensive Development Area Zone?” I have no idea.

- What is the “Waterfront Concept Plan?” Also, no idea.

- What is actually being proposed that requires a change “to allow commercial, office and residential units?” Does someone want to build a Tim Hortons or an apartment building or a single-family house?

Apologies for my flippant indignation, but surely, after the buckets of money that has been poured into inane “smart communities” projects in the city over the years, the least we citizens can expect is a clear, well-organized public notice about a public meeting with links to relevant resources; proper execution of our role as citizens would seem to require no less.

As mentioned in this space last week, today was the day that many of the architects of Charlottetown held open houses as part of Architecture Week.

The weather didn’t cooperate: hurricane-force winds and driving rain made the prospect of strolling the streets of downtown from firm to firm somewhat unappealing. But I was not to be daunted: if we are to teacher our architects to become more socially engaged, we must seize every opportunity, especially when it is they who are doing the opening.

I started off closest to home at BGHJ, a firm I know well not only because my office is in the house once occupied by the B and H, but also because I know B, G, H and J, as well as the uncredited S, as friends as much as architects (I also interviewed both J and B as part of my video series on climate change two years ago). They are arguably the most social firm in town: their annual party is a renowned for its excellent food, good music and diverse company.

Architect S welcomed me at the door to BGHJ and put me in the capable hands of Carol, an architect intern, who responded with enthusiasm and patience to all of my arcane questions like “what’s the difference between architects and architectural technologists?” and “if you had to design seniors homes for the rest of your life wouldn’t you go crazy?” I was joined by another audience member half-way through the tour, and together we got to see exciting sections of the office like “the shelves where we keep the sample catalogs” and “the couches” (it turns out that architecture firm open houses are much more interesting for the people, and (mostly) not at all interesting for the infrastructure).

I came away from BGHJ having learned a lot about “working drawings” and how they’re made, and the role they play in the construction process, and also about how architects take a sketchy vision from a client – “we’d like a house like this…” – and turn it into something the client can afford, that is physically possible, is well-designed and original (hint: it’s complicated).

BGHJ is runner up for “Best Food” (cookies, grapes and coffee) and wins the award for “Otherwise Most Hard at Work During Open House.”

Down Queen Street and around the corner to North 46, another firm I have more than passing familiarity with because of their Rform side-project, something that’s managed by principal architect David Lopes’ brother Paul, who’s a friend.

N46 was seemingly less prepared for holding an open house (no food, for example, and a somewhat surprised look when I showed up looking for action). But they made up for it with enthusiasm.

As at BGHJ, I was handed over to an interning architect and given a quick tour of the office. Fewer sample catalogs than BGHJ, and a smaller space to start with, so the tour was over as quickly as it started. My fellow tourer and I were then ushered into the board room and taken on an interesting journey through the working drawings for the new Holland College Centre for Applied Science and Technology, which N46 designed and project-managed.

All the talk about working drawings had me wondering about where Rform fit in: I knew a lot about it from the technology side from Paul, but not much about it from the architect’s side. David caught wind of this thread, and this led into a very thorough and interesting discussion about and demonstration of Rform, using the Holland College building as an example.

In addition to learning even more about working drawings and change orders and other aspects of the paper side of making buildings, I came away realizing that the day-to-day life of the small town architect is a lot more mundane than I’d imagined. I went in thinking “Frank Gehry drinking scotch and dreaming wild and crazy spacial dreams” and came away realizing it’s all far more about carpet samples and sheet rock tolerances and what to do if the concrete doesn’t dry.

North 46 receives the award for “Most Enthusiastic Product Demo” and another for “Best Integration of Recently Completed Actual Project in Open House Tutelage.”

Back out into the hurricane and along Grafton to Pownal, left, and down to the corner of Sydney to Open Practice, the firm operated by Aaron Stavert. I first met Aaron in the spring of 2010 when I wandered into his office and found him a kindred spirit; later in the year he was one of the participants in our Pecha Kucha in New Glasgow where he spoke about Sustainable Architecture (are you beginning to notice a theme here: PEI is a very small place, and everyone knows everyone).

Aaron’s practice is the smallest of those that I visited: just a single room, Aaron and an intern. There was nothing to “tour,” technically, as it once you walk in the door you’ve seen it all. But I did get a chance to ask Aaron about his seemingly impossible floor, which is made out of cheap coated particle board of the sort that you’d imagine would have dissolved by now simply from the occasional spilled cup of coffee, to say nothing of the rigours of Island winter boots. But it’s in excellent shape, and Aaron explained that when a part wears out you can simply peel off that section and lay down a replacement for less than $10.

The open house at Open Practice was more “kitchen party” than “tour,” with a changing cast of characters over the hour I spent there. Conversation ranged from “so, if you were the architect working on the Dominion Building, would you have chosen those windows?” to “does Charlottetown really need a new convention centre?”

Things really got interesting when Aaron pulled over a model of the house he’s designed for himself for Upper Hillsborough Street and took us all on a cook’s tour of its whys and wherefores.

Open Practice is hands-down winner for “Best Food” (hot apple cider, tiny cupcakes, fresh blueberries and blackberries, pumpkin pie) and also for “Best Description of a Personal Project by an Architect.”

With the hour drawing late and only another 20 minutes of the 2:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. open house window left, I dashed up Sydney Street to the corner of Queen and up the stairs over Ta-ke Sushi to the office of William W. Chandler Architects.

I worked a very little with Bill Chandler, the principal architect, back in the late 1990s when we were both involved in the Gateway Village project (he as architect, me as installer-of-Macintoshes and partner of museum exhibit builder Catherine) but I don’t know him well.

When I arrived at the firm it appeared deserted but for a slideshow running in the board room and some sparking water on the table. This turned out to be due to this being only the shared second-floor space and not the heart of the firm. Bill was fetched for me and we immediately launched into a tour of their facilities, which are vast and make for a compelling tour.

Chandler Architects and related firms are spread our over the third floors of three buildings on Queen Street – on the corner above Ta-ke Sushi, Burke Electric and China Garden – as well as the aforementioned second floor space at the corner. All of the third floor spaces are interconnected, and they’re an interesting mixture of “attic” feeling spaces and straight-ahead office spaces. They do all their own printing in-house so there’s a large print shop at the back (with the largest cutting mat I’ve ever seen). And there are interesting views of the courtyard in the back formed by the Olde Dublin Pub, Fishbones, the Globe and the buildings along Queen.

After the tour of the rabbit warren Bill took me back to the board room and we spent a long while talking about the convention centre that’s being built at the foot of Queen Street that his firm has designed. I got a look at the final renderings of the building, along with a conceptual drawing of a possible later-stage addition that engineering allowances are being made for that might one day see an extension of the Delta Hotel rise out at the end (it’s actually quite interestingly designed and works in a way you wouldn’t initially think it would).

I came away with a much deeper understanding of a building that, to this point, I’d only see renderings of in news stories about the project.

Chandler Architects wins the award, obviously, for “Most Interesting Tour” and also for “Best Description of a Commercial Project by an Architect.”

I didn’t manage to complete my entire dance card in the allotted time – I missed out on Coles Associates on the waterfront and Architecture 360 in Rice Point. Fodder for next year’s Architecture Week, I hope.

Thanks to the Architects Association of PEI for organizing this excellent opportunity for we civilians to learn more about what they do and how they do it.

Catherine and I have been dating now for 20 years. Because we don’t have the convenience of a wedding day to mark our anniversary, by tradition we use October 5. This is the date – you can read more about it here – when we first kissed, and that’s a pretty good place to start counting.

Over the years we’ve been together I’ve made up grander and more elaborate stories for Catherine’s initial characterization of our relationship back in the day.

I tried to convince her last week that her words were “we’ll stay together as long as I dig you.”

But, in truth, I’m pretty sure Catherine has never uttered the phrase “dig you” in any context. And that the essence of what she was communicating was “we’ll stay together as long as it’s the right thing for both of us.”

I liked her so much, I was down with whatever terms she wanted to describe us in. And, besides, although I didn’t have the “smashing the shackles of the patriarchy by not entering into a historically ownership-based state-sanctioned relationship” rhetoric to back it up, I had no great compulsion to get married anyway.

Moving across the country, buying a house, having a son, settling into the routines that, from the outside looking in (and often from the inside looking out) look awfully like the life of a young married couple: they’ve all added layers of complexity and commitment to that original model, but when you scrape that all away, I think we’re both solidly still in the “as long as it’s the right thing for both of us” camp.

Besides, I do still dig her, and I’m pretty sure she still digs me. What more could someone ask for?

(Photo of “20” by Bright Tal; Creative Commons licensed)

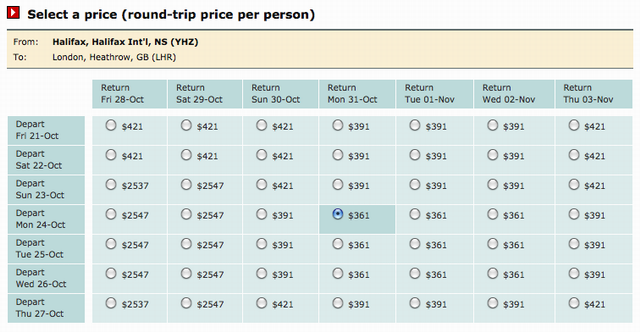

“Wow,” I say to myself, “Air Canada has terrific fares from Halifax to London.” Terrific like $361 return, which, at least on the surface, is the airline’s lowest fare on this route in years:

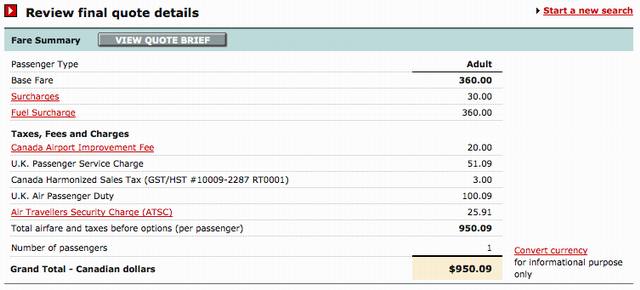

After selecting specific flights for these dates, though, the “deal” of a $360 return fare somehow adds up to $950.09, or almost $600 more than the fare first seemed:

I have no issue with Air Canada not including the items beyond its control – taxes and charges that the airline collects on behalf of governments – in the fare quote, but charging a non-specific “surcharge” of $30 and a “fuel surcharge” of $360 additional, seems just plain wrong to me.

Air Canada’s fare for Halifax to London return is $750, not $360.

I don’t have an issue with that $750 fare and, indeed, air travel should be more expensive than it is. But we wouldn’t condone being charged a “warming fee” at the coffee shop nor a “sidewalk clearing fee” at the hardware store, and we shouldn’t condone the artifice of late-stage surcharges for airline bookings.

It’s time that Air Canada simply and honestly communicated, up front, what it costs to fly.

In what is either the most or least brilliant acquisition of my life, I’ve purchased a Golding Jobber No. 8 letterpress, a press that looked like this back in the day and that weighs about 1,000 pounds more than the tiny Adana Eight Five I’ve been printing on for the past year.

Golding Jobbers are big to start with, and the No. 8 is particularly so; John Falstrom, the self-confessed “Golding nut” who helped me identify the model, called it a “BBBBBBBiiiigggggg press.” And it is: not only does it weigh, well, more than I can possibly conceive of, but it will print up to 15 by 21 inches.

In other words, were I to employ an army of printers, I could set and print a modest daily newspaper with it.

This is, at least right now, much more letterpress than my amateur needs dictate, but letterpresses don’t come on the market in Prince Edward Island very often (this is likely the last one of this size to ever come of the market), so I had no choice.

But now I need somewhere to house it.

Worst-case scenario, I’ll put it into storage until the right space comes along, but it would obviously be preferable to move it once, so I’m actively seeking a suitable rental location:

- prefer downtown Charlottetown, or at least walking distance from downtown Charlottetown, but I’m flexible,

- must be heated; prefer to have access to sink, and washroom,

- minimum 150 square feet,

- no need for general public access: can be a garage, basement, loft…

- ideally a separate space with a lockable door,

- and, most important, must have a floor capable of supporting 1,000 pounds.

I’m also open to renting a larger space and relocating my entire office/shop operation there (which would require slightly less grungy space, and 400-500 square feet with washroom), or to purchase rather than rent if a fantastic space came along.

If you’ve got space to rent please get in touch with me; if you know someone who might, please pass this post along.

I took a trip out to Campbell’s Printing in Tryon this morning – they are retiring after more than 30 years in the business – to see what equipment and supplies they might be selling that might help me in my letterpress printing exploits. I came away with a near-lifetime supply of business card blanks, a couple of composing sticks, and a box full of various and sundry letterpress “cuts” – engravings in metal of graphics, logos and text.

Among the cuts was this one – the original is only 3cm wide so what you see here is digitally blown up many times – of a boat. You can only barely read the “Put, Put” in the original.

This “special offer” for shaving supplies (the original is 4cm wide):

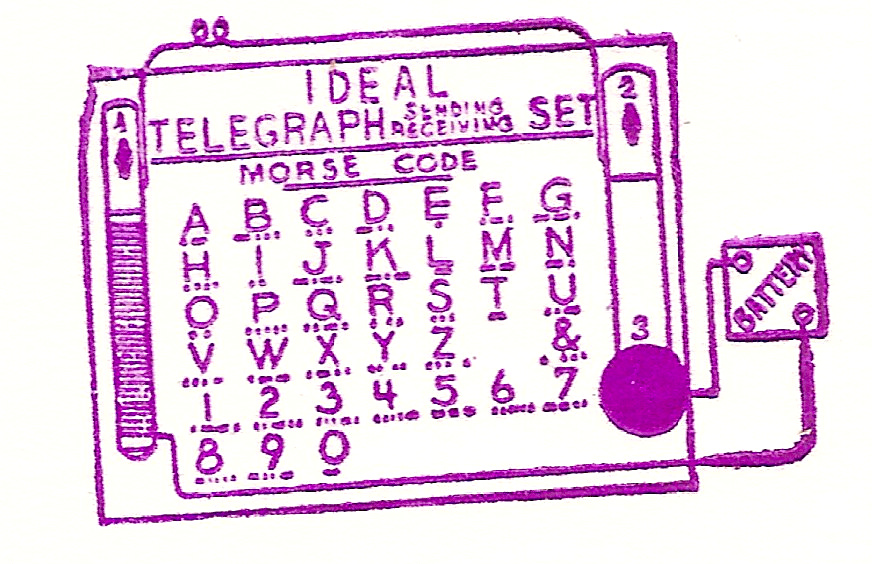

And this intriguing “Ideal Telegraph Sending Receiving Set” graphic (original 3cm wide):

The Campbells are about the nicest printers you could ever meet, and they generously took me on a cook’s tour of their shop. There are a couple of larger items I’ve got my eye on now; just need to track down some downtown space capable of supporting 1,000 lb. pieces of machinery…

My friend Oliver Baker emailed today looking for some photos I might have. While I was gliding through my iPhoto I came across this photo of Oliver (wee Oliver, my son, and Oliver Baker’s namesake) and me wearing kippot. This will do nothing to dispel the myth, common in some circles, that young Oliver and I look alike.

I am

I am