Here’s something that happens to me everyday: I’m working on coding a Drupal module and I need to use a function that I know I’ve used elsewhere, and I want to use that earlier case as an example.

What I’ve done to this point is to try to remember where I used the function, then open that code in BBEdit and do a multi-file search for the function name. This is neither reliable nor particularly efficient, so I took a moment to create an Alfred Workflow to solve the problem (Alfred is an excellent “how did I live without this?!” app that is very good for solving this sort of problem).

Here’s how I did it:

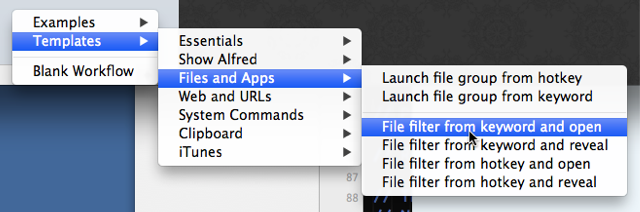

First, I created a new Workflow (from the Alfred “Workflows” tab I clicked the “plus”) and selected the “File filter from keyword and open” template:

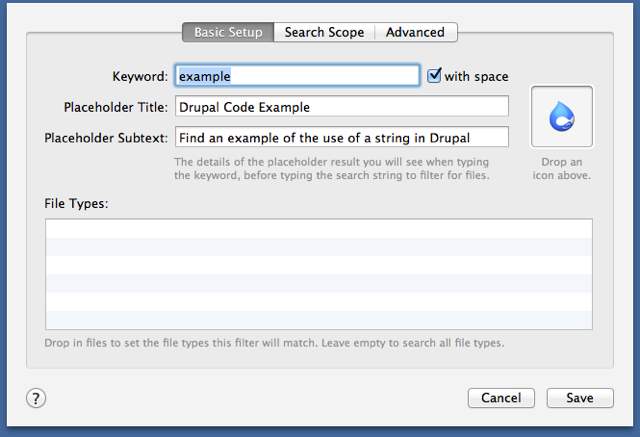

I then modified the template to create an Alfred keyword “example”:

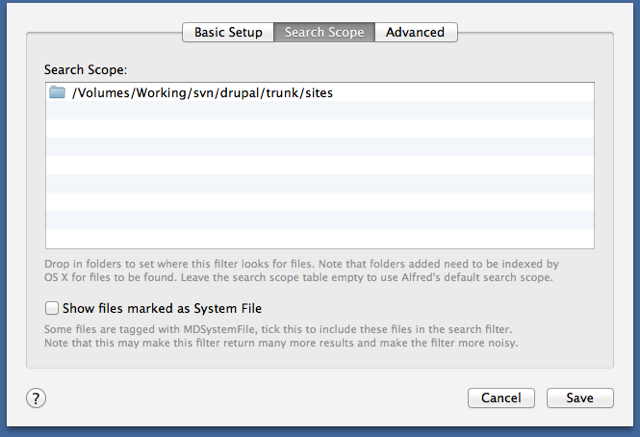

Under the “Search Scope” tab I dragged-and-dropped the Subversion working copy of my Drupal “sites” filter, where all my custom Drupal code lives:

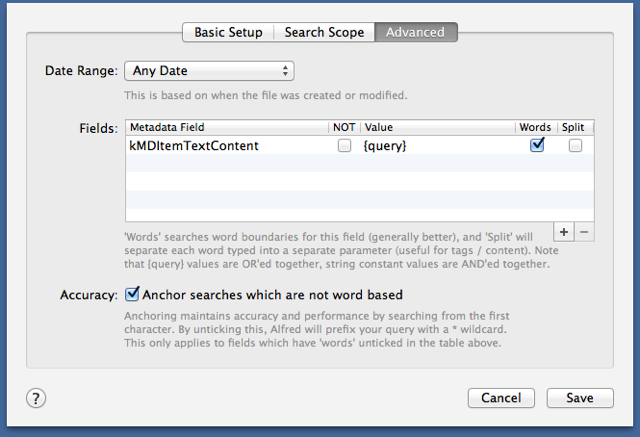

And, finally, under the “Advanced” tab I modified the “Fields” section to use the “kMDItemTextContent” field (the contents of the files):

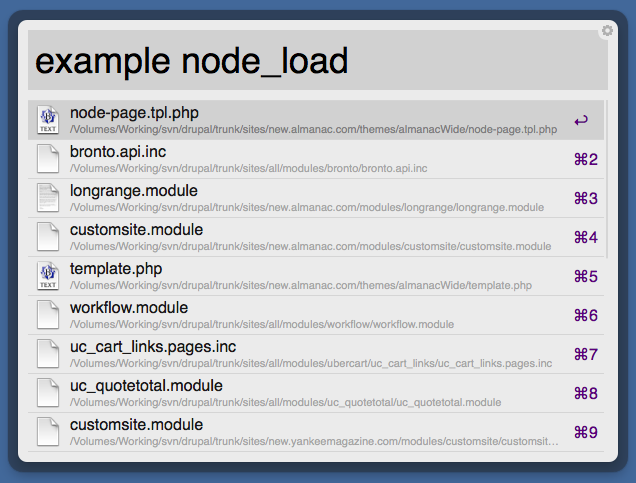

With this Workflow in place, I can now simply activate Alfred (Control+Space) and type something like example node_load (if I want to see code where I’ve used the node_load function); I see a list of files that contain that string and I can select one, hit “enter” and the file in question opens in BBEdit.

Nothing about this is Drupal (or BBEdit) specific, of course: you could use a similar Workflow in many different environments to solve the same sort of problem.

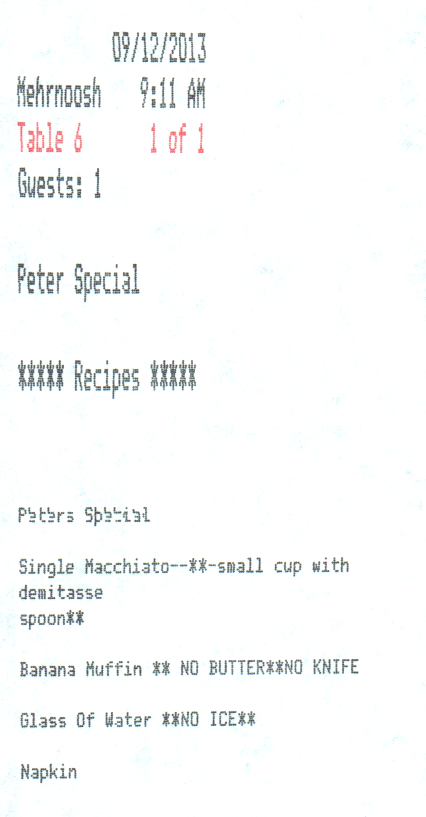

For many years my friend David has had his own special at Timothy’s Coffee; the details escape me, but it’s along the lines of coffee, toast and a copy of the Globe and Mail. I’ve always been jealous of David because of this, and so I’m doubly happy the Casa Mia Café, where I have coffee and a muffin every morning, is about to lauch “Peter’s Special” when their new point-of-sale system launches. I got a sneak peak this morning and Mehrnoosh, personable co-owner of the café, showed me what prints out at the kitchen when a “Peter” is ordered:

This is, among other things, an excellent exemplar of my persnicketiness – “small cup with demitasse spoon” and the like – and I love it.

Of course there’s nothing to prevent you from ordering “Peter’s Special” yourself if you want to join the demitasse, no-butter, no-knife, no-ice revolution. I’ll let you know when it’s available.

The 222nd edition of The Old Farmer’s Almanac goes on sale today across North America. On Prince Edward Island you can buy your copy of the Canadian Edition at:

The 222nd edition of The Old Farmer’s Almanac goes on sale today across North America. On Prince Edward Island you can buy your copy of the Canadian Edition at:

- Sobeys

- Atlantic Superstore

- Coop stores

- Shoppers Drug Mart

- Walmart

- Home Depot

- Indigo

and in better book and magazines stores across the Island.

When you buy the Almanac, you’re not only getting a useful resource filled with reference information and a “pleasant degree of humour,” but you’re also helping to support we here at Reinvented Inc., a Prince Edward Island business that’s been managing the web presence of the Almanac for the last 16 years (which seems like a long time until you realize it only 7% of the publication’s long lifetime!).

Remember to look for the real Almanac when you go to the newsstand, the one with the yellow cover.

I’ve become a big fan of the work of Transom.org, a project of the Massachusetts-based non-profit Atlantic Public Media that “channels new work and voices to public radio and public media.”

Two episodes of the project’s podcast caught my ear:

- Of Kith and Kids concerns the Plas Madoc Adventure Playground in North Wales. It’s a well-told story and one that makes me want to immediately move to North Wales to escape the wrath of litigious child-coddling that so infects us in North America. I love the distinction between “hazard” and “risk” and wish this distinction could be part of our discussions about education and play and technology here in Prince Edward Island. The same producer is making a documentary about adventure playgrounds fuelled by a Kickstarter that deserves support.

- Diary of a Bad Year: A War Correspondent’s Dilemma looks at the life of a way correspondent through her own eyes, and is the kind of self-reflection from journalists that you rarely read about outside of their post-retirement memoirs. It’s honest and disturbing and compelling.

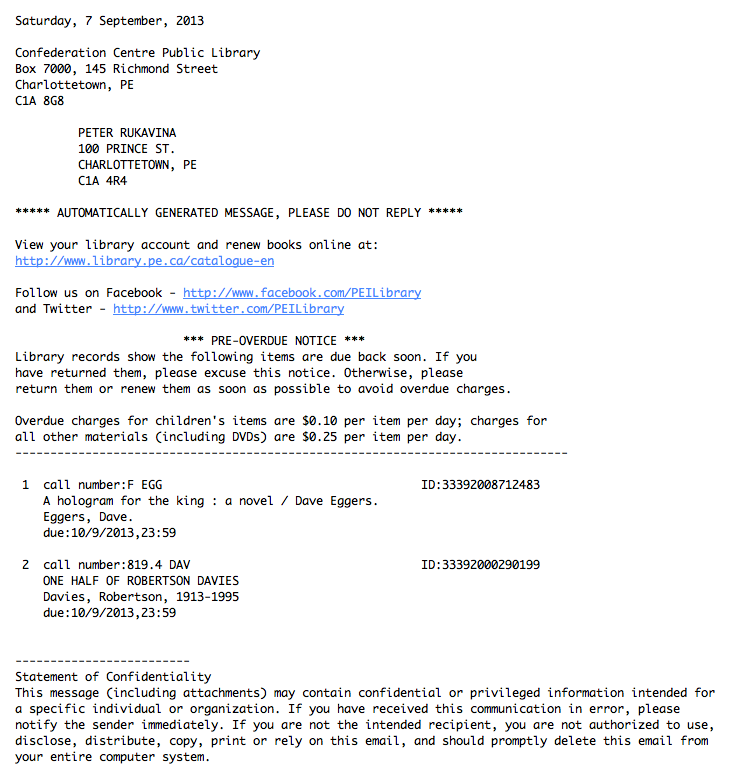

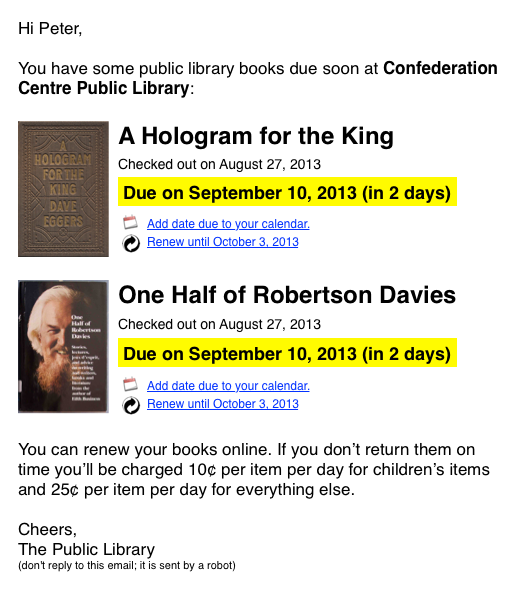

In June I recommended that we work to improve the “courtesy emails” that are automatically emailed to patrons from Robertson Library. The situation with the Prince Edward Island Public Library Service is even worse, as they try to cram in even more relevant-information-obscuring text; here’s an email I received today:

What I need to know from emails like this is:

- What books are due?

- When are they due?

Everything about the email should be judged as to how effectively those pieces of information are communicated.

Information that I do not need that’s in the email:

- The date (it’s already in the date stamp of the email itself).

- The mailing address of the Confederation Centre Public Library.

- My own mailing address.

- Links to the library Facebook and Twitter accounts.

- The “ID” numbers of the books (meaningless).

- The wordy introductory paragraph (we all know how libraries work; this doesn’t need to be re-explained).

- Statement of Confidentiality (meaningless).

What’s worse is that the “when are they due” information is presented in an ambiguous format: are the books due on September 10 or on October 9?

For an email that’s all about the date, that’s an important thing to be clear about.

Here’s a prototype for a replacement email:

The Vinyl Cafe is a much-beloved long-running CBC Radio programme hosted by Stuart McLean. The heart of each episode are the “Dave and Morley stories,” tales of a fictional Canadian family and their misadventures. And the stories are – quintessentially – Canadian, filled with the kind of wry self-deprecating humour that is at the heart of our national psyche.

Stuart McLean’s telling of the stories is also quintessentially, well, Stuart McLean, filled with expectant pauses and told with a masterful sense of comic timing. So much so that for years I thought that Dave and Morley were real, only to have the wool pulled away from my eyes by my brother; I emailed McLean to complain, and he replied, kindly, with a wink and an apology.

Those pauses: they are epic. Almost a character in the story themselves.

Here, for example, is a 14 second snippet of the Gabby Dubois episode that aired a few weeks ago:

Just look at that waveform: signature Stuart McLean.

Indeed here’s the same snippet, but with the pauses hand-edited out; you lose 4 seconds (30%) of the clip in the process, and much of the impact:

Listening to an episode of the show this weekend, I realized that those pauses were a key to hacking the Vinyl Cafe: if I could split a Dave and Morley story into chunks by splitting on the pauses I could then remix the story into, well, whatever I wanted. Fortunately the open source toolkit was chock full of tools to make this surprisingly easy on my Mac. Here’s how I did it.

Chop out Dave and Morley

From the Vinyl Cafe podcast feed I downloaded an episode of the show, the same Gabby Duboid episode I took the snippets from above. I then used Audacity to locate and copy-and-paste the Dave and Morley story into a new file, and saved this as an MP3, which I called gabby-dubois.mp3.

Split on Silence

To split the story into chunks based on silence I used the mp3splt program, like this:

mkdir silence mp3splt -d silence -s gabby-dubois.mp3

The result was the new silence directory filled with 326 small MP3 files, each a chunk of the story.

Glue Together at Random

The opposite of mp3splt is mp3wrap, which glues MP3 files together from the command line. I decided that it would be interesting to take the 326 small chunks of the Gabby Dubois story and randomly stick them back together to make an entirely new story. I did this like this:

cd silence mp3wrap ../gabby-dubois-random.mp3 \ `ls | \ perl -MList::Util=shuffle -e 'print shuffle(<STDIN>);' | \ tail -n 255 | \ tr '\n' ' '`

This sequence of commands has the effect of doing the following:

- Listing all the files in the silence directory.

- Sorting this list into random order (using Perl).

- Taking the last 255 randomly shuffled files (because mp3wrap has a limit of 255 files).

- Stripped out the carriage returns at the end of each file.

- Feeding the result as the list of files to combined to mp3wrap, with the resulting combined file called gabby-dubois-random.mp3.

The Nonsensical Result

Here is the nonsensical result, which sounds somewhat otherworldly because there’s little convey to that it’s not an actual story other than that it doesn’t make any sense. The pauses are still there, which is why it works as well as it does. Listening to it I find that my brain strains very hard to make sense of what’s happening. But it can’t.

My family moved to the small village of Carlisle, Ontario in 1973. It was a sort of toned-down “back to the land” effort by our parents: no cows or chickens or wind power or yurts, but certainly a move toward the rural from our previous house in suburban Burlington.

The house in Carlisle, on Progreston Road, had 2 acres of land, all of it cleared. The previous owner had purchased a barn at auction some years previous and had disassembled it and moved it, and so much of the back yard was littered with lumber of all shapes and sizes that needed to be gathered, cut up and, in some cases, turned into sheds, a task that, for we boys, seemed to stretch on for hundreds of weekends.

Once the barn was cleared out of the way our parents set out on an ambitious reforestation plan, purchasing tiny seedlings and, with Mike (age 6) and me (age 7) to help, covered the back half of the lot with trees. Again, it was a process that, to our young minds, seemed endless and backbreaking and, perhaps, pointless.

Then 40 years passed.

And here’s what’s there now:

And here’s what it looks like on the Google Satellite map:

What an enormous gift our parents gave Mike and I forty years ago: from here in the future being able to see tiny seedlings transformed into a forest of trees taller than we could have imagined demonstrates what’s possible in a lifetime, and shows the value of being patient.

Next Tuesday the moving trucks will show up at the house on Progreston Road and our parents will move out of that house – back to Burlington just a few miles from where they lived in the late 1960s, as it happens – and a new family, with a young daughter in tow, will move in.

Mom and Dad and Mike and I made her a forest to play in. That’s pretty amazing.

We were out the door at 8:00 a.m. this morning – the bell at St. Paul’s Church had just started to chime – and headed up Prince Street, as we have hundreds of times since Oliver started school.

Today, however, was different: at the corner of Kent we turned right. Down Kent to Hillsborough, cut across Kings Square, up Weymouth to Ken’s Corner, across the perilous “intersection that nobody understands” and along Longworth (saying “hello!” to the crossing guard) to Birchwood Intermediate School where Oliver starts grade 7 this morning. It’s 11 minutes from door-to-door.

First Day of Grade One

|

First Day of Grade Seven

|

We were warned that Birchwood would be chaotic and cacophonous this morning but it was neither. We chatted with the guidance counsellor – she too is moving from Prince Street to Birchwood, so was an old hand – about the meaning of the Birchwood school motto, “Prima Primo” (or is it “Primo Prima”?) which seems, oddly, to mean “First First” in Latin.

While this motto appears ceremonially throughout the school, the website is emblazoned with “Quality Education in a Caring, Disciplined Environment.” I suppose that’s not a bad sentiment, but it could also describe a military school or a dog training college. I would prefer something like “A Laboratory for Discovering Self, Community and the World,” but nobody listens to me.

Our experiences at Birchwood to date have been universally positive: we were in for a tour and a chat on Tuesday, got Oliver set up with his locker and introduced to his homeroom teacher, and saw his classrooms (including the wood shop, sewing lab and cooking lab).

Birchwood has a lot of room to ramble around in now that the Spring Park students, temporarily housed there for a couple of years while their new school was under construction, have returned home; this means there are a lot of rooms available for small-group teacher, special products and so on. We’ve lucked in to the small “intimate” junior high in Charlottetown: last year Queen Charlotte had 456 students, Stonepark had 773 while Birchwood had a modest 232. There are four grade 7 classes in the school (one of which is an 8-student late French immersion class); Oliver has 23 students in his homeroom class, which is larger than any class he’s even had, but still well within reason.

So far, so good.

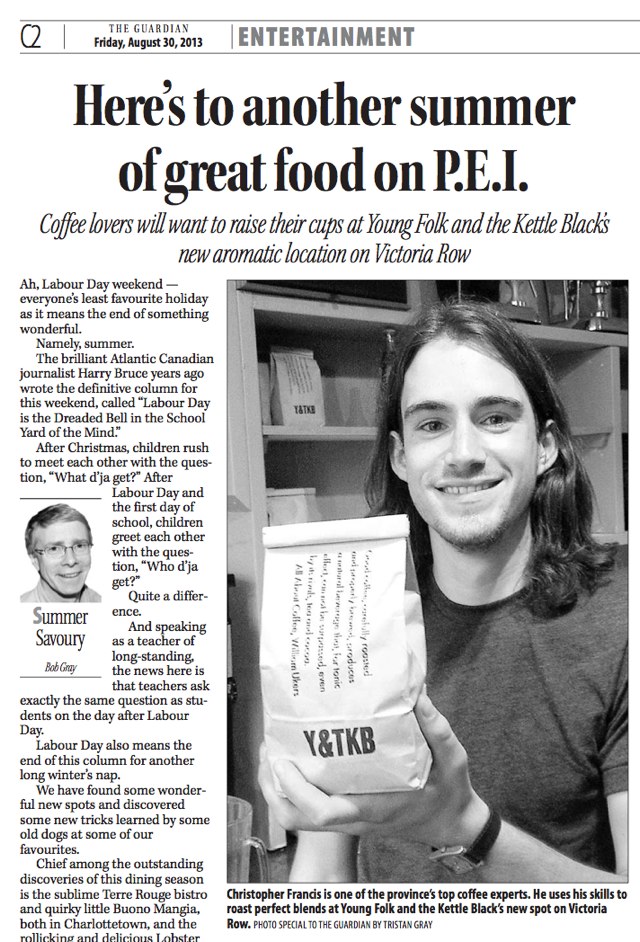

While I was in getting coffee at Youngfolk & The Kettle Black this afternoon, personable owner Adam Young mentioned to me that the coffee bags I printed for them on the letterpress featured in Bob Gray’s review last Friday. I tracked down the digital edition of the paper and, sure enough, there they are:

There’s a colour version of the photo online it you’d rather.

I created Checkin, my Firefox OS Foursquare checkin app, as much to learn about Firefox OS as to scratch my own checkin itch. The next step along this road was to “localize” the app: in short, to make it work in languages other than English.

I tried four approaches to getting the translations for the words and phrases in the Checkin app done:

I tried four approaches to getting the translations for the words and phrases in the Checkin app done:

- I emailed friends who speak Portuguese, German, Danish and Swedish. I have helpful friends: each sent me back their translation within a couple of hours.

- I set up a project at the crowdsourced translation site GetLocalization.com and requested translations into the remaining languages the Firefox OS is set up for. I did this 24 hours ago, and so far I’ve had no translations offered by the “crowd”, but I did have one person double-check the German translation.

- I set up a similar project at the crowdsources translation site Crowdin.net with similar results: 24 hours in and nobody has translated anything.

- I set up a project at the pay-per-word translation site Gengo.com, which specified $2.40 US per language for the 40 words I needed translated. I ordered translations for Polish, Spanish (Spain), Spanish (Latin America), Chinese (Traditional), Portuguese (Brazil), Arabic and Hungarian. The translations were completed in between 15 minutes (Hungarian) and 9 hours later (Polish), with the majority of them completed with two hours. The service was easy to use, easy to set up, and there was a helpful interface for clarifying translation details (like “does CHECKIN mean to ‘to enter’ as in a hotel or does it mean ‘to verify’?”)

Once I had all the translations done, I needed to set up the app to use them. The post Localizing Firefox OS Apps from Mozilla proved very useful in this regard. I simply needed to pull out all of the strings from the app – things like “Enable Foursquare?” and “Checked in” – and put them in language-specific “properties” files that look like this:

settings = Settings enable-foursquare = Enable Foursquare? currently-disabled = Currently disabled. foursquare-instructions = To enable Foursquare checkin, check the box above and authenticate yourself to Foursquare. confirm-checkins = Confirm checkins? confirm-explanation = Require confirmation every time? checkin-confirmation = Checkin to checkedin = Checked in. gps-waiting = Waiting for GPS gps-explanation = Waiting for the GPS to return your current location.

On the left of each line is a key that I’ll use later in HTML and JavaScript to reference the string; on the right is the translation for the language in question (the example above is the file checkin.en-US.properties, which is used on English-language devices). So, for example, here is the same file but for Spanish:

settings = Configuración enable-foursquare = ¿Activar Foursquare? currently-disabled = Actualmente desactivado. foursquare-instructions = Para activar los check-ins de Foursquare, marca la casilla de arriba e identifícate en Foursquare. confirm-checkins = ¿Confirmar los check-ins? confirm-explanation = ¿Solicitar confirmación siempre? checkin-confirmation = Realizando check-in checkedin = Check-in realizado. gps-waiting = Esperando GPS gps-explanation = Esperando a que el GPS devuelva tu ubicación actual.

Once all of the properties files were created, I created a locales.ini file that referenced each of them. Here, for example, is this file set up for English (the default language) and Spanish:

@import url(checkin.en-US.properties) [es] @import url(checkin.es.properties)

With the properties files and the locales.ini set up, getting the translations into the app required two steps: editing the HTML and editing the JavaScript.

In the index.html for my app I needed to reference the locales.ini and also the l10n.js script that I copied from the Gaia repository:

<link rel="resource" type="application/l10n" href="locales/locales.ini" /> <script type="application/javascript" src="js/l10n.js"></script>

Then in the places in the HTML where I wanted to use a translated string I simply added a reference to the key in the properties files like this:

<h1 data-l10n-id="settings">Settings</h1>

That has the effect of displaying either Settings (if the app is displayed in English) or one of الإعدادات, Indstillinger, Einstellungen, Configuración, Beállítások, Ustawienia, Configurações, Inställningar, or 設定, depending on the language of the device.

In the JavaScript I do a similar thing, but using the navigator.mozL10n.get function:

$('#statusmessagetext').html(navigator.mozL10n.get("checkedin"));

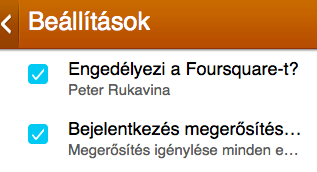

That’s it! Running Checkin on the Firefox OS simulator and changing the device language changes the language of the app: when the device is set to Hungarian, the app appears in Hungarian. It’s really quite magical.

I’ve two remaining challenges:

First, Arabic is a right-to-left language, but my app isn’t set up yet to account for this, so although the app is translated into Arabic, it still appears left-to-right. It seems like there are hooks in the Gaia UI building blocks, so I expect that, with some digging, this should be relatively easy.

Second, there are some translations that are longer in another language than in English, and the Firefox OS stock UI isn’t handling these well. So I see things like this, in Hungarian:

I’ll have to figure out a way around that too.

The updated multilingual version of Checkin hasn’t appeared in the Firefox Marketplace yet; if you want to install it in your device, though, you can grab the app from Github and install it. Recommendations for improved translations are welcome.

I am

I am