By the fall of 1996 I had been working on the website of the Province of Prince Edward Island for over a year and we were well on the way to expanding the site from its tourism-information roots to becoming a comprehensive website about all of the various activities of the provincial government.

That November the first provincial general election was called since the website first went online in 1995 and so a meeting was arranged with Chief Electoral Officer Merrill Wigginton to discuss the possibility of posting election-related information on the site.

Merrill did not warmly embrace this opportunity – recall that these were early days not only for the web on PEI, but for the web itself, and he was justifiably suspicious – but, to his credit, he agreed to let us experiment, and so what quickly followed was a page of general electoral information along with a tool for finding your district and poll (this was before the days of Island-wide civic addressing, so the tool was a blunt instrument).

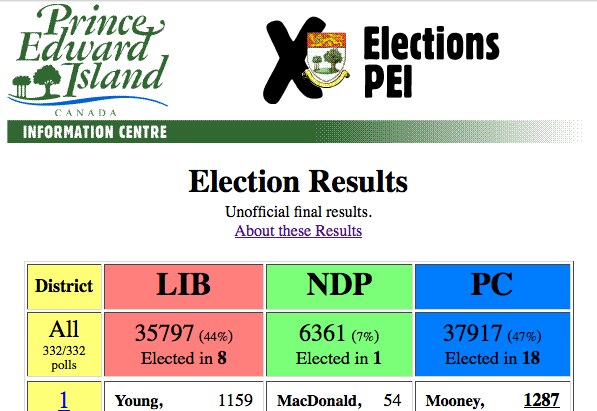

On election day, November 18, 1996, I was at “election central” in the Studio Theatre of the Confederation Centre of the Arts to take the results of the election and post them online. As befit my “temporary suspension of disbelief” status at the time, I was the last in line to receive the results: they were telephoned in from the districts to a bank of clerks who transcribed them onto sheets of paper, then handed to data entry clerks who entered the data into a PC-based results spreadsheet from which occasional reports were printed for distribution to the media, to the political parties and, eventually, to me. So the results posted online were not exactly “live,” more like “liveish.”

By the end of the night the Keith Milligan Liberals had fallen to the Pat Binns Progressive Conservatives. Not only had the government turned, but, as someone whose livelihood depended on maintaining the government’s website, so had my employer (to the credit of parties of both stripes, the website was a refreshingly non-political venue, and my position survived two turnovers of government).

In the 17 years since that first election, I did the same thing for five provincial general elections in total – 1996, 2000, 2003, 2007 and 2011 – and saw the government swing back the other way, from the Pat Binns Conservations to the Robert Ghiz Liberals in the process.

After its initial skepticism, Elections PEI quickly warmed up to the Internet to the point where the route that election results followed on election night for subsquent elections was telephone-Internet-PC-printer-media. Indeed, eventually the media stayed home on election night and used the Internet instead, as we began to feed results directly to them and to Canadian Press.

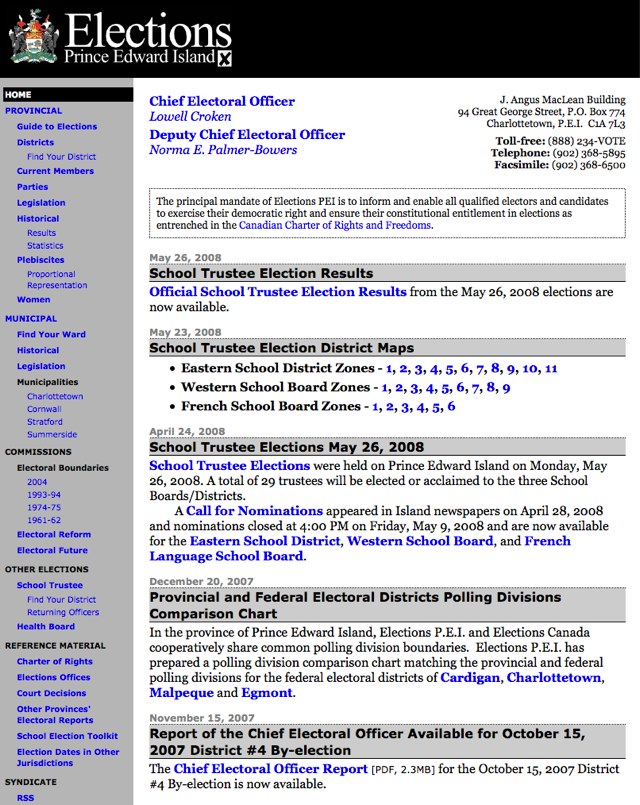

Behind the scenes, additional embracing of web was happening too: for its public website, Elections PEI moved to its own domain name – from www.gov.pe.ca/election to www.electionspei.ca – and we worked with the office to add a rich set of historical resources, an enhanced civic-address-based electoral district finder, and more information about how and where to vote during election periods.

In more recent years I was joined in all of this work by my brother and Reinvented colleague Johnny who ably did his own fare share of Elections PEI website updating, Register of Electors training and support and election night data entry.

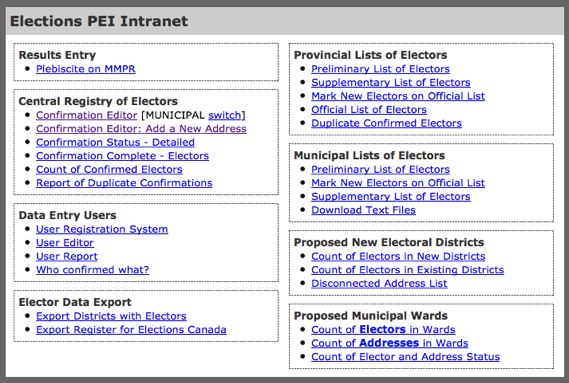

When the provincial Register of Electors was introduced – a permanent database of the name and address of every qualified elector – a system was required to manage the gathering and maintenance of the data. Merrill Wigginton, by this point a strong proponent of web technologies, sketched out a system for making a web-based system to do this, and we built the system to his spec, using it for the first time in the 2003 election. (It’s worth noting that this and every single piece of software we wrote for Elections PEI used open source software exclusively: Apache, Perl, PHP, MySQL and a host of other applications and utilities from the open source community).

By the summer of 2003 I was winding down my work on the provincial website – the way I’ve always explained this was that there came I time when I had to either manage or be managed and I wasn’t comfortable with either prospect – but I agreed to stay on under contract to continue to manage Elections PEI’s technology.

For me this was something predicated on two things:

First, it was work I enjoyed: being in the engine room of democracy is thrilling, and the technology challenges I faced (like “how do you make a web system that won’t crash when 97,180 people try to look up the election results at the same time on election night”) were compelling.

As much or more, however, was that I enjoyed working with the people of Elections PEI: over 17 years I worked closely with Merrill Wigginton, Lowell Croken, Norma Palmer and Judy Richard, and a host of temporary workers and returning officers during election periods, and they were universally kind, smart, witty people with a passion for democracy and logistics both.

No more so were both factors – good challenges and good people – in evidence as on election day in 2003 when, as I detailed here at the time, a hurricane struck the Island the night before the election; everyone pulled together, though, and the election was held, people voted and everything worked as it should. That experience cemented a lot of work relationships and was no small part of my agreeing to stay on as part of the Elections PEI operation.

And that’s how, for the past decade, I continued to work with Elections PEI on its technology infrastructure.

The Register of Electors system became more sophisticated for the 2007 provincial general election: it was used to create “Confirmation Forms” for every civic address in the province, 60,000+ printed forms that were created by merging data from the Register with PDF files. After the door-to-door confirmation process where this information was cross-checked against the situation on the ground, these forms were then reassembled and we gathered with a team of 100 public servants in the Shaw, Sullivan and Jones buildings to have the database updated. We repeated the process in 2011, and for two rounds of municipal elections and a few byelections along the way.

The system that allowed all that to happen is one of the creations of which I am most proud: it had to work – the Election Act said so – and, as it was being used to create the Official List of Electors, it had to work well. We have some amazing administrative assistants in the provincial public service, and it’s a testament to their skills that almost 100,000 names and addresses were updated in less than 48 hours for three elections in a row.

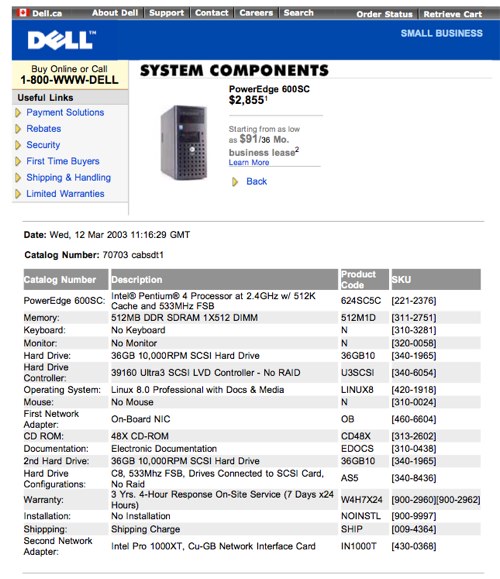

Somewhat miraculously, all of this – the election results system, Elections PEI’s website, and the Register of Electors – was hosted, for over a decade, on a pair of Dell PowerEdge 600SC servers located on the second floor of a two-floor vault at Elections PEI’s headquarters at 180 Richmond Street, a “server room” that made bona fide system administrators cringe every time they saw it, for it lacked both backup power and any air conditioning, and regularly got up to 30°C+ in the summer heat. But the servers – nicknamed wallis and edward – just kept on going and going and going. The edward server – it hosted the MySQL database server and the internal web services – had its fan die a few years ago, but we simply removed the cover to add additional cooling and it kept on going.

Early in 2012 two things appeared near in the horizon. First, edward and wallis needed to be replaced: servers don’t last forever, and those two were certain to have a hard drive or power supply go eventually. Second, Lowell Croken and Norma Palmer, Chief and Deputy Chief since 2005, announced they were going to retire before the year was out.

Working with Elections PEI we began talking with the province’s IT Shared Services group about purchasing new servers, and this evolved into a conversation about taking over maintenance and administration of the technology itself.

My 17 year working relationship with Elections PEI was an unusual and perhaps unique one; I knew that, for the long term, not only did edward and wallis need replacing, but I needed replacing too, so that the office could have a long-term, sustainable technology platform for the future. So, over the last year, along with Elections PEI, I’ve been planning for this migration.

Norma Palmer retired in mid-2012 and Lowell Croken retired in January of 2013; it took me and edward and wallis a little longer, but last month the switched got flipped and IT Shared Services took over administration of the Elections PEI website, the Register of Electors and the election results system, all now safely ensconced on modern hardware in an air-conditioned, fire-protected server room with a staff to oversee it.

I spent more than half of my professional life working with Elections PEI in one form or another; I honestly never stopped loving it. Democracy, especially when viewed from underneath the bonnet, where you see how hard everyone works to make sure everyone can exercise their franchise, is a lovely thing, and I was honoured to be given the opportunity to be so closely involved its logistics.

Best wishes to Norma and Lowell in their retirements, best wishes to new Chief Electoral Officer Gary McLeod and his Deputy Judy Richard, and hats off to the staff at IT Shared Services for a smooth migration. I’ll be thinking of you when you’re down in democracy’s engine room when the next election rolls around; for a change, all I’ll need to worry about on that day is voting.

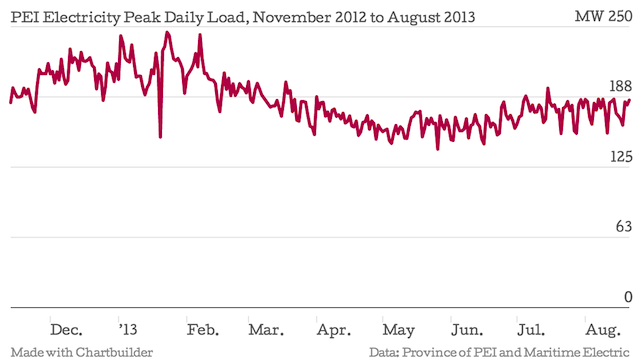

I have been archiving Prince Edward Island energy load and generation data since November and I’ve created various tools, like this graph and this gauge and this mobile app to put this data in my “peripheral view,” with a goal of making myself more aware, in a visceral way, of how much electricity we’re generating and using here on the Island.

One of the things that’s surprised me is how much electricity we use here in the summertime. A frequently-offered explanation for part of the increase in overall electricity usage is the shift to electric heating; so you’d expect the summertime usage to be lower than the wintertime usage. And it is. But by much less than I would expect. Here’s a graph that shows the “peak daily load” from November 2012 to August 2013: this is the highest Island-wide electricity load, in megawatts, for each 24 hour period.

During this period, the day with the highest peak load was January 23, 2013, with 245 MW, and the day with the lowest peak load was May 26, 2013 with 140 MW.

But look at August 1, 2013: the peak load on that day was 185 MW, which was higher than the peak load of 183 MW on February 15, 2013 when the temperature never went above 2°C.

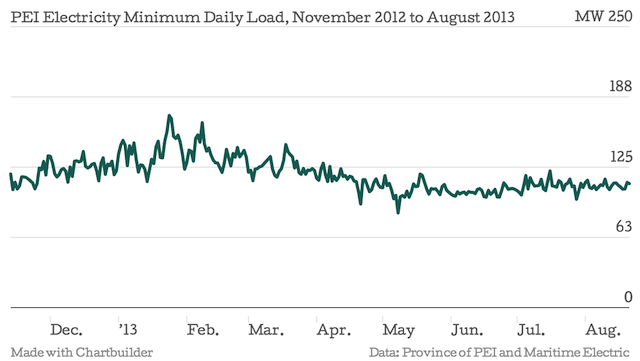

Perhaps even more interesting is a graph showing the miniumum daily load – the least amount of electricity we’re using in any given 24 hour period:

It’s a rare day when the minimum load dips below 100MW. That seems like a lot of electricity to be using a 4:00 a.m.

One of the great things about looking at the electricity portion of our energy usage is that, because it’s centrally generated and distributed, it’s easy to measure in aggregate. One of the frustrating things is that nobody – not Maritime Electric, not the Province of PEI – really knows what is using all that electricity. Of course everyone has educated gueses – perhaps it’s ground-source heat pumps or air conditioning, for example – but that’s just a best guess.

Thoughts?

One of the more satisfying aspects of my Mail Me Something project is getting to see things I’ve printed on the letterpress popping up all over the world as envelopes arrive, are unsealed, and photos posted on Instagram, Twitter, Path and Facebook (it’s also a good measure of the speed of various post offices: in order things have arrived, so far, in Tyne Valley, Berlin, Düsseldorf, Mount Stewart, Peterborough (Ontario) and Malmö).

Photos, from top to bottom, by Jonas, Jonas, Heather, Peter and Pedro.

This isn’t quite getting hoist on my own petard, but apropos of What makes you a “well-known businessman” in The Guardian?, I note that of the 53 references to my various exploits that have appeared in The Guardian in the last 20 years, one of them, appearing on the August 10, 2002 edition, was titled “City businessman ticked that bank is frozen in time” and starts:

This could be a case of someone having too much time on their hands.

Peter Rukavina said Wednesday he is frustrated that the clock on the front of the main Charlottetown branch of the Bank of Montreal on Grafton Street has been stuck at 6:38 for the past six months.

So, he has formed Citizens for Correct Time (number of members: 1, but he said he’s working on more).

The problem with the clock, he said, has got to stop … er, start.

“My family and I live and work in downtown Charlottetown,” said Rukavina, a Charlottetown businessman. “We pass by the broken clock three or four times a day. The fact that the clock is broken means we’re not only without a handy source of the current time, but it’s an embarrassment for the community: it says ‘look, we don’t even know what time it is here’.”

Perhaps not one of my nobler pursuits, especially when you consider the result of the “action”: rather than fixing the clock, the Bank of Montreal simply removed it altogether.

At least I wasn’t referred to as a “well-known city businessman.”

(For that matter, I have no idea why I was referred to as a “businessman” at all).

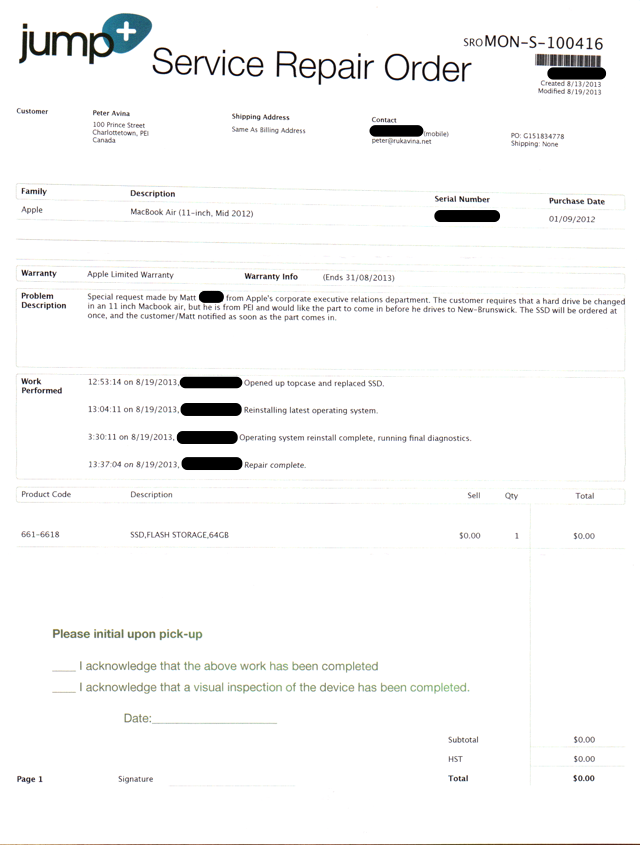

Oliver’s MacBook Air broke. I got frustrated trying to get it repaired. I emailed Tim Cook at Apple about my frustration. Tim Cook’s office replied, and took on the case. We drove to Moncton. Oliver’s MacBook Air got repaired.

In an article on August 16, 2013, The Charlottetown Guardian newspaper referrred to Tim Banks as a “well-known businessman” (emphasis mine):

The provincial government is lending a total of just over $8 million to well-known businessman Tim Banks for an expansion of the redevelopment of the former Kays Bros. Building on Queen Street in Charlottetown.

Which prompted me to ask, via Twitter, “What is the threshold that causes @PEIGuardian to refer to someone as ‘well-known’?”, to which The Guardian replied:

@ruk Appeared in at least two Guardian articles? If someone says the name in the newsroom, we all say, “Oh yeah, him!”?

This made me curious: just what does trigger “well-known businessman” in The Guardian? So I decided to try and find out. From the UPEI Robertson Library record for The Guardian I made my way to the “Eureka” service, which holds a full-text archive of the newspaper (UPEI campus login is required to access this).

Here are all the occurrences of “well-known businessman” appearing in The Guardian in the last decade:

- The provincial government is lending a total of just over $8 million to well-known businessman Tim Banks for an expansion of the redevelopment of the former Kays Bros. Building on Queen Street.

- Griffin says [Wade] MacLauchlan is a well-known businessman and highly respected academic who has demonstrated a strong commitment to building better communities.

- Lt. Michael Campbell, a well known businessman, volunteer, and local board representative will act as host for the event.

- Murphy is also known to many Islanders as the wife of well-known businessman Danny Murphy, franchise owner of Tim Hortons and Wendy’s on P.E.I…

- A well-known businessman and sports lover who passed away at the age of 92 last year, [Edmund] Gagnon was considered a giant in the world of junior hockey and played a significant role in helping to establish the sport in New Brunswick.

- A well-known businessman and facilitator behind the Small Halls Festival, [Ray] Brow said it’s time to say goodbye to any long-distance charges in this province.

- [Harry T.] Holman, a wealthy and well-known businessman, purchased land in 1910 with the idea of building a home for his family.

- Well-known businessman [Peter Williams] offers for capital’s council.

- [Jospeh] Spriet, president of the 2009 Canada Games Host Society, is a well-known businessman who lives with his family in Valleyfield.

- “I’m here as a friend and neighbour on behalf of friends and neighbours,” said [George] Beck, a well-known businessman who was asked to act a spokesman for what he said was a large portion of residents opposed to the pay increase.

- Wayne Buote, a well-known businessman and community supporter in the Rustico and Cavendish areas, died suddenly on Sunday at his home in New Glasgow.

- He also said there is absolutely no connection between [Kevin] Murphy’s appointment and cabinet’s decision to hand the well-known businessman $250,000.

- Well-known businessman [Tim Banks] agrees with Charlottetown’s last-place finish in Maclean’s survey.

- Keith MacLean, a well-known businessman and member of P.E.I.’s construction industry, died Friday at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Charlottetown.

- Well-known businessman and Tourism Advisory Council chair Kevin Murphy says he believes the Provincial Nominee Program was good for P.E.I. tourism operators, and admitted that he personally benefitted from it.

- Well-known businessman Elmer MacDonald dies.

- Well-known businessman and entrepreneur William (Bill Sr.) Hambly died at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital on Monday, Aug. 6. He was 87.

- But her father Robert [MacLean], a well-known businessman himself, took her aside with some advice.

- Roger Birt, well-known businessman in the Charlottetown area who has flourished with residential properties and commercial real estate.

- The Conservatives Best Hope For A Breakthrough In Prince Edward Island Is In Charlottetown, Where Well Known Businessman Tom Deblois Is Hoping To Turn The Capital City Blue On Monday.

- Chamber president Derek Nicholson presented the President’s Award to well-known businessman and town fire chief Harry Annear, who was shocked when called to the podium.

- The announcement was made this week by Mayor Richard Collins who said he was delighted the well-known businessman [Merrill Scott] and former town mayor agreed to take on the task.

- The mural on the Hardy building at the corner of Church and Main streets will honour the life and times of well-known businessman Gerald Rooney (1914-1983).

- He’s the son of well-known businessman Orin Carver, who passed away a few years ago.

During that same decade there were no references at all in The Guardian to “well-known businesswoman” and no references to “well-known businessperson”.

This brings to mind Jane Ledwell’s talk at Confederation Centre Public Library last year where she sought to answer the question “are women mentioned less-frequently in media in general.”

We held the Make Your Own PirateBox Workshop this morning, as scheduled, in Confederation Landing Park. Six people registered for the workshop: of these, two people sent regrets at the last minute and one person didn’t show up, so total attendance was four, including me.

We gathered under the gazebo at the end of the park, which turned out to be a great location, given that it was a sunny, breezy late-summer day. After chatting about PirateBox in general for 20 minutes, we dove in an set out to make ourselves some PirateBoxes.

Among the bumps we encountered along the way:

- Several of the PirateBox installation steps require the router to be tethered via wired Ethernet cable to a host PC; modern Macs don’t have a built-in Ethernet port, and so unless you bring the “dongle” that adds and Ethernet port, your PC can’t be used for this step. This was an error I made at PirateBox Camp in Berlin last month – I left the dongle for my MacBook Air back here in PEI – and it was something that one of our number forgot this morning.

- Unless you do a 100% “use a PirateBox to make other PirateBoxes” install – which is something that we went through at PirateBox Camp, but which I wasn’t set up for this morning – you the router to have Internet access via wired Internet to install PirateBox itself. I thought we were going to be able to pull this off by using mobile phone GSM Internet access via wifi tethering with a host MacBook Air and then sharing that connection with the Ethernet port, but we never quite got that working. After 90 minutes of fiddling with various possible options – including an attempt to use a virgin TP-Link MR3020 to do what it’s actually designed to do – share Internet via wifi – we gave up and retired to my office up the street to use its wired Internet. After that, things went as planned.

- The Achilles heel of the install process is the vi editor that is used to change the network configuration half way through the install; while there’s a pointer to a cheat sheet included in the instructions, vi is just too weird for the uninitiated and so lots of “this is going to get really technical” disclaimers are required.

- Once vi has been mastered and the network configuration changes, the rest of the install process pretty well happens on its own and that part worked flawlessly.

The workshop broke up about 1:00 p.m. with two new PirateBoxes having been built – one person, our dongleless one, had to leave early. It was a good learning experience for how (and how not) to conduct a PirateBox workshop; everyone in attendance was patient and open to learning.

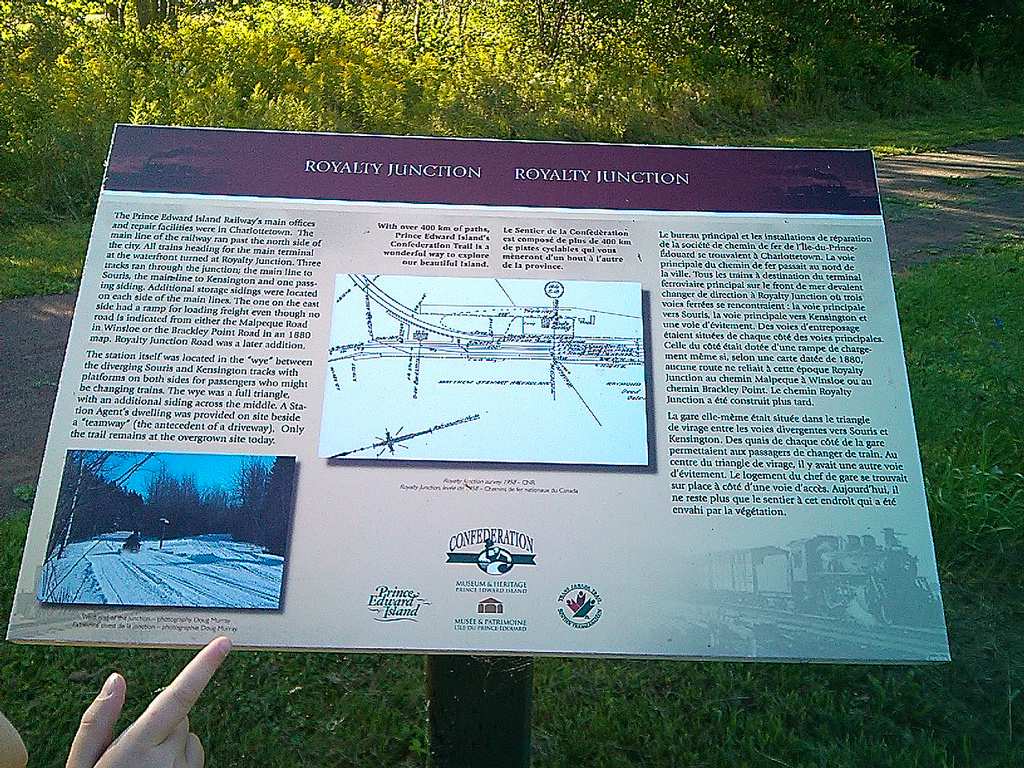

I have long been curious about Royalty Junction, the spot north of Charlottetown where the east-west railway line met the Charlottetown railway line. I could never figure out why I never ended up driving through Royalty Junction until today when, looking for a place for Oliver and I to take a quick later-afternoon walk, I came to realize that it’s a junction that doesn’t actually directly abut any roads. Here’s what it looks like from the air:

The historical plaque posted at the junction describes the it as a “wye”, which it clearly is looked at from any direction you might approach it in. Here’s Oliver illustrating this very fact:

The plaque goes on to describe the function of the junction:

The station itself was located in the “wye” between the diverging Souris and Kensington tracks with platforms on both sides for passengers who might be changing trains. The wye was a full triangle, with an additional siding across the middle. A Station Agent’s dwelling was provided on site beside a “teamway” (the antecedent of a driveway). Only the trail remains at the overgrown site today.

Royalty Junction is a really easy place to visit, as it turns out, and you can even visit without a car, as the “T3 Winsloe and Airport Connector” bus will drop you off nearby.

You can join the Confederation Trail in Winsloe where it crosses the Winsloe Road near Red Oak Landscaping (this is just 5 minutes walk from the PetroCan where the bus will let you off). The loop along the trail, through Royalty Junction, bearing off toward Charlottetown and then cutting back across to Winsloe on the Royalty Junction Road takes 45 minutes to an hour depending on how much dawdling you do. Here’s a map showing the route:

To make the journey by bus most conveniently, take the 1:45 p.m. University Avenue #1 bus from Confederation Centre of the Arts to the Charlottetown Mall where you’ll transfer to the 2:00 p.m. T3 Airport and Winslow Collector line toward Winsloe. Get off at the Winsloe PetroCan at 2:13 p.m. Spend a pleasant hour doing this trail loop, stop for a coffee at the Tim Hortons inside the PetroCan, then catch the 3:43 p.m. bus back to the mall, rendezvousing with the 4:00 p.m. bus south on University Avenue which will put you back downtown for 4:15 p.m. Can you get that much nature and that much heritage without driving a car anywhere else?

There’s a lot of Arthole to love, but my deepest love is reserved for the piece by Donnalee Downe titled The Mailroom: 59 Love Letters.

It really is 59 letters, 59 from-real-life-written-to-Donnalee love letters, each hanging, carefully catalogued and labelled, from a taut wire running along one wall of the gallery. We patrons are invited to become a part of the art by reading, editing and/or shredding any of the letters.

As Arthole is mounted in the basement gallery of The Guild, mere steps from the Reinventorium, I resolved to spend a little time each day reading a few of the letters. I made it through 5 minutes before I had to suspend the plan: the letters were just too difficult to read, too self-involved-20-year-old-angsty, too I-ache-to-see-your-breathy, too much a reminder of my own love letters from back in the day.

Which left me seeking another way of engaging with the piece.

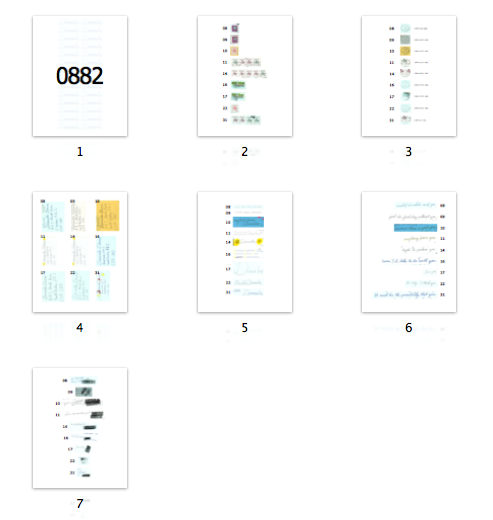

So this morning Oliver and I hauled my little Doxie scanner down from the office to the basement, scanned the letters and envelopes from August 1982, came back upstairs and made a book. It’s called 0882 and it’s a different kind of slicing and dicing of the raw material. It was really fun to make.

I printed off three copies at Staples this afternoon – their 39¢ colour copies did a nice job of this, and the cerlox-binding-machine at Robertson Library did the rest – and left the books in the “edit bin” downstairs in the gallery. Where, I suppose, they are now a part of the piece too.

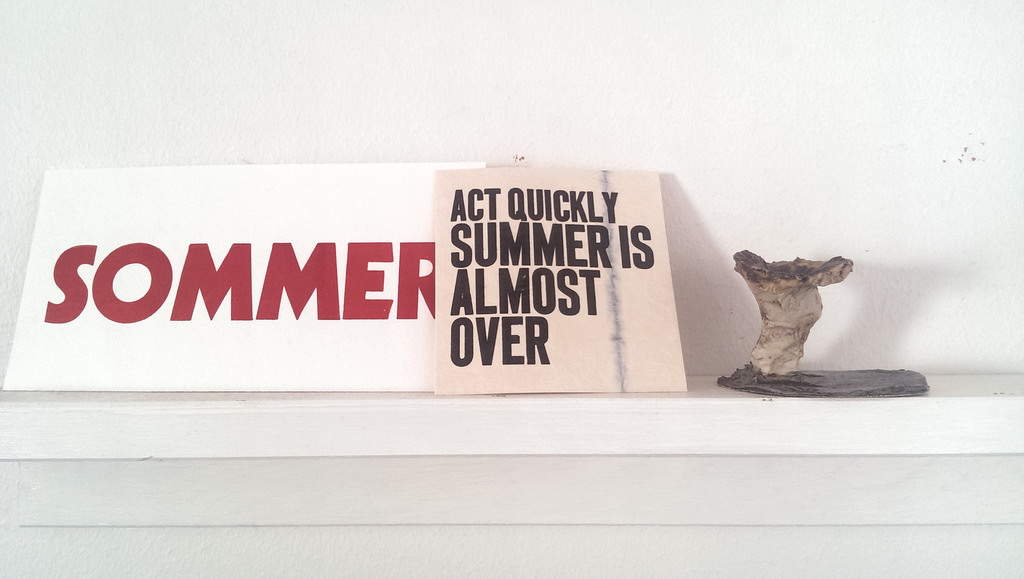

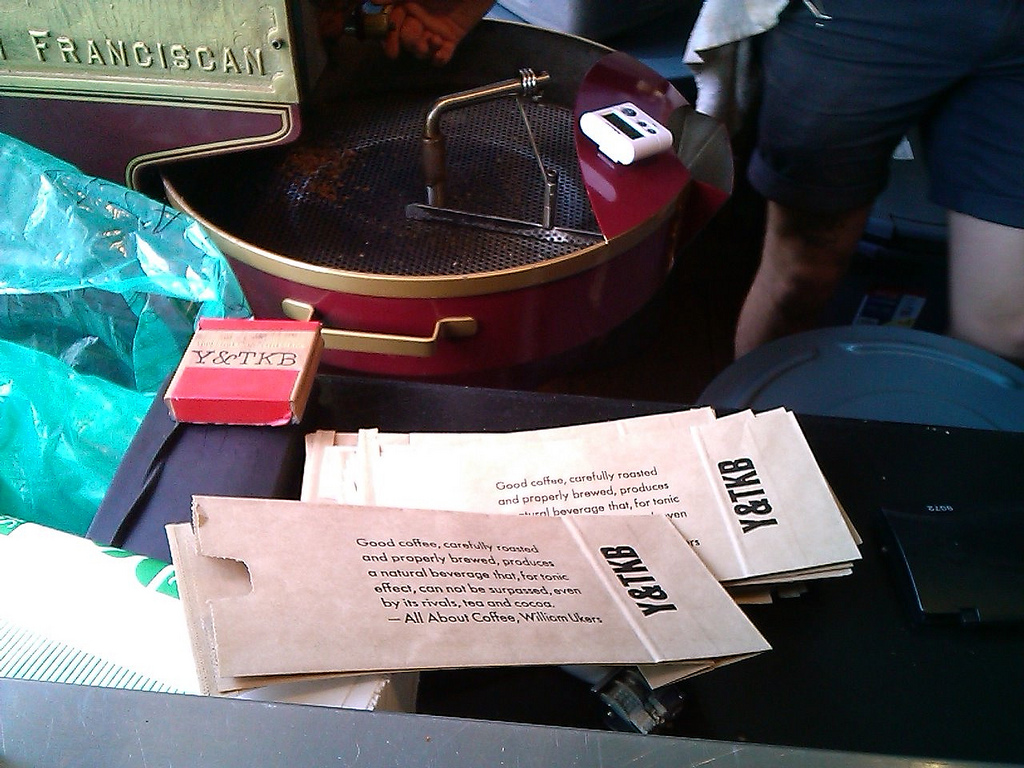

The coffee bags I designed and printed on Monday? On Tuesday morning they were on the shelf at Youngfolk & The Kettle Black on Richmond Street filled with coffee and ready for sale. I can’t tell you how enormously satisfying this short “press to shelf” window is; it’s like digital design timelines have been transposed into the analog realm.

I only printed 85 bags, so if you want your “Kettle Black Blend” in one of these bags, act now.

I am

I am