I got my first POTS (plain old telephone service) line when I was 17. I had it installed in my room at my parents house. I used it mostly for dialing into the various BBS systems of the day. But it was also the line I used to (nervously) call Ruth Lane-Smith to ask her out on a date (in the end I’m not sure she completely realized it was a date).

When I moved to Trent University I had a line installed in my room in Champlain College and from there, with a brief summer off when I went telephone-free in the destroyed ruins of 107 Hazlitt Street, I’ve had an analog telephone line running into wherever I’ve lived.

Over those 30 years I had 2-party lines and 4-party lines, lines from Bell and lines from Island Tel and lines from Eastlink. I used dial up at 150 baud. I remember when it cost 25 cents a minute to call Summerside from Charlottetown. And when calling “overseas” was a once-or-twice-in-a-lifetime thing.

On Monday, with the the porting of our number at home to Vitelity (an Englewood, CO voice-over-IP provider I’ve been a happy customer of here at the office for many years), that all came to an end. Vitelity just started to offer local number porting for Charlottetown numbers this year, and when I heard I jumped at the opportunity to consolidate all my phone service onto one bill and feeding into one PBX (an Asterisk box sitting in the server room over at silverorange HQ).

So my monthly phone bill now looks like this:

- Home phone: $2.99/month plus $1.49/month E911

- Office phone in Charlottetown: $2.99/month

- Local number in Dublin, NH for clients: $1.49/month

Those monthly fees appear artificially low compared to what I’m used to paying Eastlink (about $25/month depending on how you yank it out of the bundle with Internet) because I also pay Vitelity $0.011/minute for all calls in and out. But I’d have to talk for about 36 hours straight to have those minute-by-minute charges add up to the old bills.

It’s not like I’m not giving up anything in the process either: I am now my own phone company, for most intents and purposes. So if the Internet goes out, or my Asterisk box goes down, then my phone goes away. There’s none of the battery-backup-phone-never-stops-working I got when I was 17. But with responsibility comes freedom too: not only are all “calling features” free here at RukTel, but I can code up new ones in PHP.

Best of all, I can now call home from the office by dialing “100”.

(If you’re interesting in telephony history, I highly recommend Voices of the Island, Walter Auld’s history of Island Tel and telephony in general on Prince Edward Island; it’s a great read).

When I wrote about my lunch with David Ramsden earlier in the week, I took a flyer and uploaded a couple of tracks from his albums – two versions of come Inside – to Soundcloud. David found his way to my post, and wrote a kind note on Facebook where he said, in part:

When you read this, you will hear two versions of my song “Come Inside” with the lovely Rebecca Jenkins, one recorded live at the Cameron House in Toronto in 1990, the second from my CD “The Rhythm of the Lonely Road”, produced by Ken Myhr and released in 2001. Reading this today before I venture out onto the island brought a flood of memories back to me, as did our lunch yesterday.

The tracks themselves have been listened to almost 200 times since I posted them, and I asked David if he’d like me to post the complete albums to Soundcloud, to which he quickly replied “yes.” After some futzing around bringing his Soundcloud account back to life, I’m happy to announce that you can now listen to the complete albums of Quiet Please! There’s a Lady on Stage and The Rhythm of the Lonely Road on Soundcloud:

This is such a great gift to the world from David: they are great album and deserve a wide audience. Please share!

So I’ve ended up in the temporary care of 62 boxes that look like this:

Each box is 8.75” x 3” x 1.75” and weighs about 1 kg. They are wooden boxes of punches1, used to punch Monotype matrices. They are a part of the typographic heritage of North America, and my friend Heather rescued them from the dump in Mount Stewart2. I have found someone, a noble soul, in the northeast USA, who is willing to take on their stewardship, but for this to happen I need to ship the 62 boxes to him.

Canada Post tells me that the maximum weight they will ship is 25 kg, so I would need to ship them in at least three boxes. They quoted me the following prices to ship a 21 kg box:

- Expedited USA: $72.14 x 3 = $216.42

- Xpresspost USA: $123.15 x 3 = $369.45

- Priority Worldwide: $384.78 x 3 = $1154.34

I’m looking for advice from the crowd as to whether there are alternatives to Canada Post that would be less expensive; we’re doing this as a heritage-preserving non-profit effort, so the money is coming out of our own pockets. Please leave advice in the comments if you have any.

––––

1. Inside the look like this:

2. After Gerald Giampa held his auction in Mount Stewart (after he was flooded out by a tidal surge) he hauled the items that didn’t sell to the Mount Stewart dump; Heather, keen of eye and present of mind, followed him and waded in amongst the rats and the garbage to rescue these boxes. She deserves and award.

Yes, I know, I go on about this (For Public Public Spaces, Public Space should be Public, The Chieftains in Charlottetown: Is Borrowing Public Spaces Okay?).

But it’s something I believe strongly in, and I think it bears repeating: public spaces should be for the public.

But it’s something I believe strongly in, and I think it bears repeating: public spaces should be for the public.

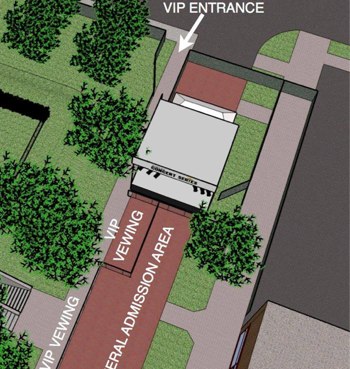

With the Joel Plasket concert set to close off Victoria Row to all but paying customers this weekend, it again means that a public space that Islanders deserve free and unfettered access to will get walled off to those willing and able to afford a $25 ticket.

Whether it’s streets or parks or squares, and whether it’s rock shows or jazz shows or theatre shows, public spaces should be public.

Ironically, there was another model for holding an event on Victoria Row that played out this week: the Open Repositories conference held a Wednesday night event on the street, booking out all of the restaurants and bringing in entertainment (Colour Code, Ten Strings and a Goatskin, among others). And yet the street itself remained open, so we residents of the neighbourhood could enjoy the music – and access to the street – as we have a right to. Private space in support of public space: that’s a good model (disclaimer: Mark Leggott, who chaired the conference, oversees Robertson Library where I am Hacker in Residence).

And last year’s Island Fringe Festival used public squares effectively, sold tickets, and yet saw no need to wall off the squares for paying customers only.

All appearances to the contrary, I’ve no problems with music filling up my neighbourhood: Wednesday’s event, and last year revivified PEI Jazz and Blues Festival were both credits to the area, and used the street effectively as a venue in a way that was open to all.

I just think it’s wrong that public spaces get walled off for the preserve of the ticketed; it’s especially egregious in a neighbourhood where many residents can’t afford the cost of a $25 concert ticket, and so must look on from outside the prison gates at the use of spaces they’ve paid for, spaces we all own, are used for the the entertainment of the privileged few.

This is entirely within the control of the City Council, for events like this require a permit; if you agree with me on this, perhaps you could let your councillor know?

A long, long, long time ago I was invited to go up to the Coles Building and meet with Allan Rankin and Roy Johnstone about this new-fangled thing called “the information superhighway” and how they might use it as musicians. I offered to midwife them into the process, and created websites for each of them more than a decade ago.

Roy took to the medium like a duck to water, and has been an active caretaker for his website, using it to update his fans, sell tracks online and distribute sheet music.

Allan did not.

And so AllanRankin.com has remained almost completely unchanged since it went online in 2002; it’s a sort of time capsule for early web design (I’ve always rather liked the site despite this).

Allan, meanwhile, continued to work as a musician and a bureaucrat both, but without any longer-lasting evidence of this until this month when, at long last, he releases a new album.

Allan is releasing the album at The Trailside this Sunday and I’ll be there in the audience.

And, eventually, perhaps I’ll work with Allan to update his website. Update: see AllanRankinMusic.ca, Allan’s new website.

My father, in recent years, has been rediscovering the popular music of the twentieth century. Or rather discovering the popular music of the twentieth century as it seems that he somehow managed to miss most of it the first time around.

And so, every once in a while, we boys will get an excited email from Dad saying something like “Have you heard about this great group called The Eagles?!”

My own small contribution to this comes from the albums, cassettes and CDs that I’ve left at my parents’ home over the years.

So in recent years my father has, for example, discovered Jane Siberry. And, this Christmas, David Ramsden. He came across a copy of David’s Quiet Please! There’s a Lady on Stage cassette in a closet, a cassette I’d thought long-lost. He digitized the cassette to MP3s and offered to burn me a CD of it, an offer I enthusiastically took him up on.

When I lived in Peterborough, Ontario in the late 1980s and early 1990s David was a fixture of the local music scene, both there and in Toronto. I encountered him in many venues and in various combinations and permutations, both as a musician and an actor (he was a sometime member of the cast of the infamous “East City” soap that played late nights at Artspace).

Quiet Please! There’s a Lady on Stage was a project David launched with some of Canada’s most talented female vocalists, singers like Rebecca Jenkins, Jane Siberry, and Theresa Tova. The combination of David’s piano and vocals with these voices was remarkable, and the cassette Dad found in the closet was the only surviving evidence of it. One of my favouite tracks on the cassette is Come Inside, which David sang with Rebecca Jenkins (still one of Canada’s great vocal talents). This digitlzed version is a little wobbly – it comes from a 25 year old cassette tape, after all – but it still captures the potent combination of the two voices:

David and I ran in the same circles in Peterborough, and although I’m not sure we ever sat down and had a conversation, we knew who the other was (I knew David’s brother Ken, mayoral candidate and leader of Reverend Ken and the Lost Followers a little better).

I don’t use Facebook frequently – every time I check in there seem to be long-unread 2 or 3 messages from old friends that were sent months ago – but in recent weeks I’ve been using it more because I had a visit from a friend through which Facebook was the only way of communicating. And so it was that I noticed, out of the corner of my eye when I logged in on Tuesday, that David was in New Brunswick, eating a bad lobster sandwich:

McLobster made me McSick. Honestly I arrived so late here in Saint John last night that it was the last place open. I should have Mcknown better.

On a lark, I sent him a Facebook message (only the second one I’ve ever sent to anyone) offering to treat him to the excellent lobster roll at Youngfolk & The Kettle Black here in Charlottetown as an antidote should he ever find himself in the city.

To my surprise and delight it turned out that he received the message as he was sitting in his hotel down the street from me in Charlottetown and graciously took me up on my offer.

Regular readers may recall that I am rather shy, and it’s quite unlike me to extend invitations to lunch to people I only vaguely know, especially people whose talents I’ve been in awe of for so long. But an invitation is an invitation, and so yesterday afternoon David and I found ourselves renewing our ties over an (excellent) lobster roll on Water Street.

David was as delightful a person as I recall – more so, even. We had a very pleasant chat, found we had more people in common that we both thought. I sent him on his way with a list of must-see places on PEI (Yankee Hill cemetery, MacAusland’s, Landmark Café, The Pearl, etc.) and before he left David went back to his car and pulled out a copy of his new album to give to me (“new” in the sense of “most recent” – it was released 13 years ago). The album was an unexpected treat – I didn’t know he’d recorded it – especially for the inclusion of a new version of Come Inside with Rebecca Jenkins:

I post this here simply because finding a notary public in Prince Edward Island has always been a mystery to me, and the answers that Google gives are unsatisfying link-bait. I know that all lawyers are notaries by virtue of their office, but in other countries there are other people “deputized” to be notaries and I wondered if the same is true of of PEI.

I stumbled upon the fact that the Prothonotary of Prince Edward Island, a public official who is, roughly, the “Clerk of the Supreme Court,” will act as a notary at no charge: he just notarized a document for me. It took 5 minutes. He was friendly.

I confirmed with his office that he’s available to do this for any Islander; just contact his office to make an appointment: (902) 368-6067.

(The only downside to having the Prothonotary notarize something for you is that you need to go through airport-style metal detectors to visit his office; the staff there are friendly enough, but it’s still an added inconvenience).

I’ve been using a Geeksphone Peak, runnning the nascent Firefox OS, as my everyday mobile phone for more than a month now. I tweet with it, I update Foursquare with it, I check my email with it, I search the web with it, I use maps with it.

In many ways it feels like 1993 all over again, back when we ran Linux 0.93 on IBM PCs and it sort of worked.

Through one lens Firefox OS is a technical triumph: an open mobile operating system conjured up in two years by a not-for-profit organization.

Through another lens running Firefox OS is like running Linux on an IBM PC in 1993: it sort of works; sometimes it crashes, sometimes the wifi mysteriously shuts itself off, and while it does a lot, and is capable of a lot more, right now it does much less than an iPod touch, if only because the ecosystem of open web apps to run on it is only just beginning.

But under the hood and, indeed, infused into almost every pore of its being, it is open. This means so many things and means so much.

It means that the documentation for developing for the OS is out in the open, not hidden behind a locked developer website.

It means that there’s an active and out-in-the-open discussion of the fundamental aspects of the OS.

It means that you (yes, you) can dial into weekly conference calls or jump on IRC and talk to the people developing the OS. Or, indeed, become one of the people developing the OS.

It means that rather than “we do not discuss future plans”, your answer to “when will feature X be added” can be found in a public spreadsheet.

It means that if you have a problem you can find an answer by looking in the source code, which is public and on Github.

It means that you can find out if the bug you’ve found is being worked on, because the bugtracker is open.

What it means most of all, though, is that Firefox OS is being developed by real people to solve real problems; it’s not built to sell you more apps or get you to buy more songs or to show you more ads more targeted at your consumer behaviour. It’s being built by people like you for people like you.

So I’m willing to put up with the disappearing wifi and the fact that I can’t (yet) upload photos to Flickr because I believe in Firefox OS under-the-hood and I want it to succeed.

To this end, I’ve been sitting down and learning about the ins-and-outs of developing for the OS. Much of the terrain is familiar, because Firefox OS apps are just HTML + CSS + JavaScript, and that’s a world that’s been my technical home for 20 years. And it’s also familiar because I’ve been developing mobile apps for iOS and Android in the same style, wrapping them up in PhoneGap for their respective app stores. But there are new APIs to learn and a new UI toolkit to flesh out.

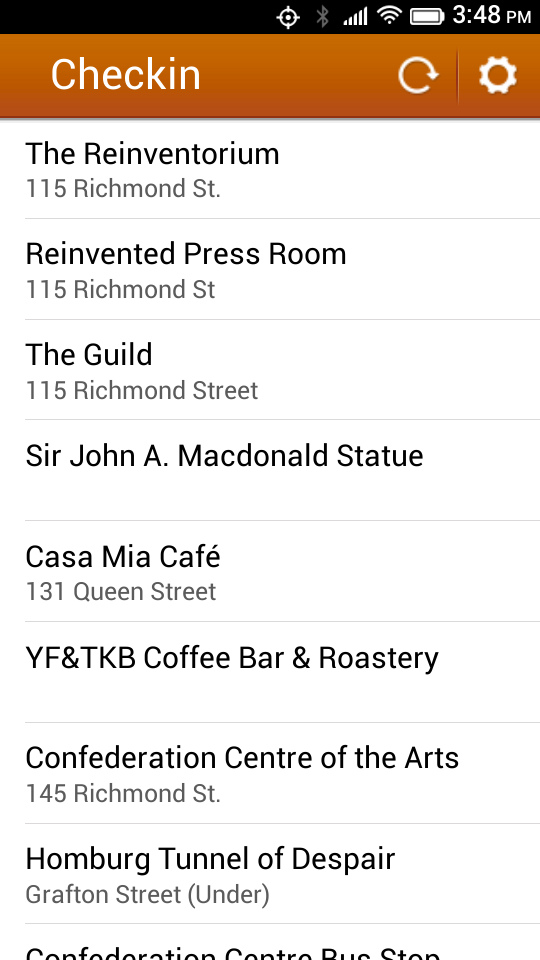

The best way to learn is to scratch a personal itch and I decided to write an app that would let me check in to Foursquare.

I’d been using Foursquare’s mobile website to do this and found it frustrating: it doesn’t know about my location, so it can’t provide me with a list of nearby places and so every time I checked in I had to manually key in the name of the place on a tiny phone keyboard.

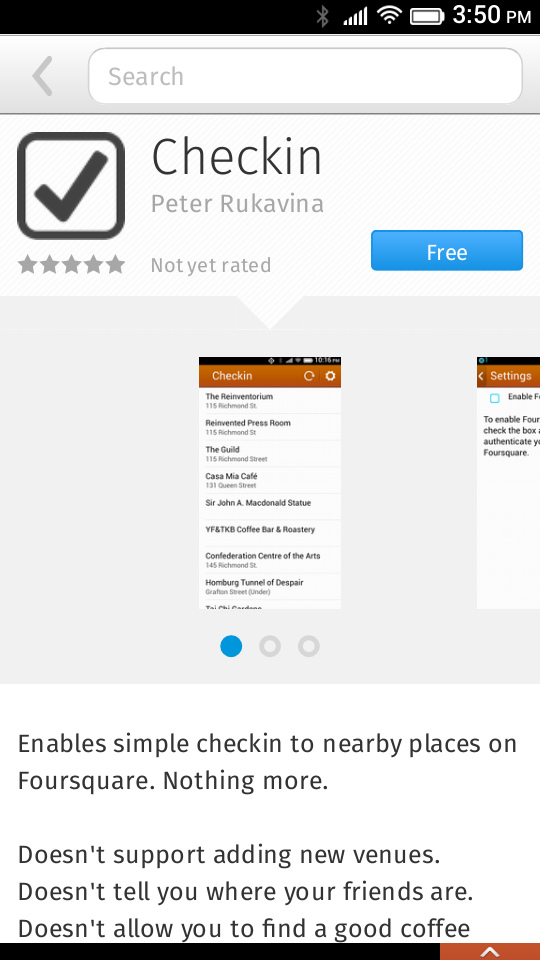

I’ve been a Foursquare user for many years, mostly using Foursquare’s own mobile apps on my iPod Touch and iPad, and I’ve always found them filled with too many features I never use: I look to Foursquare primarily as a repository for my geolocation history, and so what I really want is an app that shows me a list of nearby locations and allows me to checkin with a single tap.

So that’s what I built.

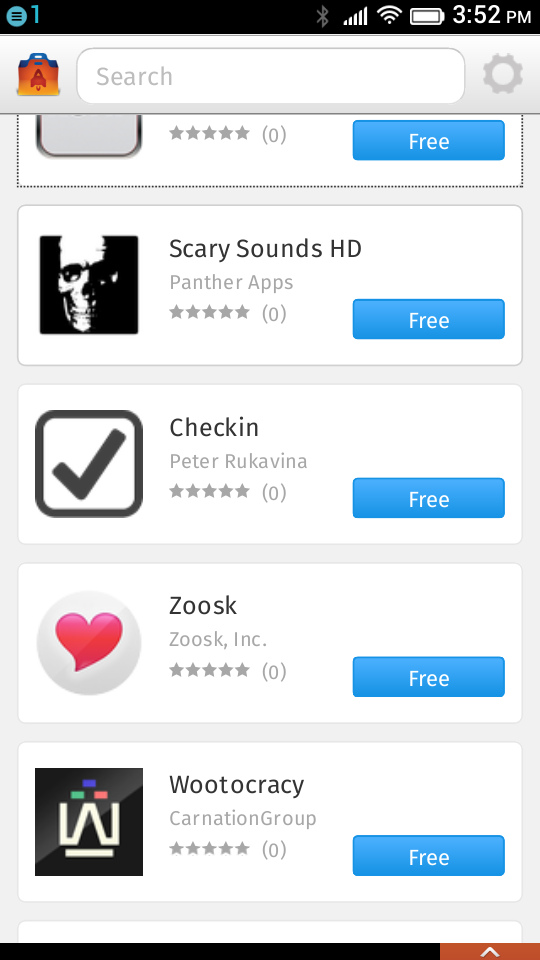

The app I coded, called Checkin, has just been reviewed and is available in the Firefox Marketplace. It looks like this in the Marketplace:

And the app itself looks like this:

I wrote the app to scratch my Foursquare itch, yes, but also to get code out there for others to build on and criticize, especially code that authenticates by OAuth to an external API (Foursquare). So you’ll also find the source code in Github (you’ll find the tricky Foursquare OAuth bits here).

A few notes about the development process, from back to front:

- Reviewed!? Didn’t you just say that Firefox OS is open? Yes, the OS is open. But the Firefox Marketplace – intended, ultimately, to be just one of many places to get packages Firefox OS apps – requires that all apps calling so-called privileged APIs be reviewed, the idea being that APIs that provide access to “sensitive” capabilities need to be approved by someone before being installable. In the case of Checkin, as you can see in the app’s manifest: the app requires the systemXHR, and browser APIs, both of which are “privileged,” and the “geolocation” API, which isn’t. I submitted the app on June 30, 2013 and it was approved today, so it took 10 days, which is about what it takes an app approved in the iOS app store.

- That all said, using Firefox on the desktop and the Firefox OS Simulator you can grab the source code for the app and install it without the Marketplace or, indeed, any intermediation.

- My original intention was to build cellular network cell-site detection into the app, using OpenCellID.org to retrieve approximate latitude and longitude of the device. Unfortunately Mobile Connection API falls into another even-more-sensitive class of APIs, “certified,” a class that, at least right now, “must be approved for a device by the OEM or carrier in order to have this implicit approval to use critical APIs”. So if I wanted my app in the Marketplace, I needed to leave that functionality out. I think that’s a bad thing, or at least an unfortunate one, and I’ve proposed that at least some of what the Mobile Connection API offers – namely the cell ID, LAC, MNC and MCC – be exposed more freely.

- Because I don’t have a way of determining the location of the device other than via the Geolocation API, the app is really only useful when the device can see GPS, which, at least for my Geeksphone Peak, means outside. Android and iOS devices have access to non-public APIs that use a combination of GPS, cell site and wifi to derive location, which is why the Foursquare app on my iPad can figure out that I’m at Casa Mia even when I’m deep inside Casa Mia out and out site of satellites.

- For the UI building blocks of Checkin I used excellent Building Firefox OS resource, which documents the building blocks used for the core Firefox OS apps. It’s not quite a mobile UI framework like jQuery UI, but it’s pretty good for simple apps like mine, and CSS transitions handle simple page transitions without the additional complexity a framework would bring (for the curious, the “main” and “settings” screens of the apps are just absolutely positioned divs that get their z-position changed to become foreground or background; I didn’t invent this, just copied from elsewhere).

- The OAuth authentication to the Foursquare API turns out to be actually quite simple, despite OAuth’s reputation (and my own previous experience) that it was a Darién Gap for mobile devlopment: the app opens up a full-screen IFRAME (hence the need for the Browser API, which enables this), sending Foursquare the client ID I set up in the Foursquare developer site along with a “redirect URI” of Foursquare.com itself; when Foursquare redirects after login and authentication the app uses a mozbrowserlocationchange event to look for an access token in the redirected URL and proceeds. Using mozbrowserlocationchange this way is another reason for the Browser API, for it’s not supported otherwise (i.e. if I just called window.open to authenticate to Foursquare).

I look forward to the app being out in the wild and to getting feedback from people using it (it’s quite possible that I’m the only person in the world who has a Firefox OS and wants a simple featureless Foursquare checkin app; we’ll see).

Oliver has had a blog, by times, at http://o.ruk.ca/. It’s a Tumblr blog, which makes it easier to update and maintain than other platforms, and it’s well-suited to kids for this reason (that said, it went away for a year because Tumblr updated its IP address for custom domain names and we didn’t update the settings, so some vigilance is required).

The blog is up and running again now, though, helped in part by Oliver having inherited my old iPod Touch, onto which he’s installed the Tumblr App. This makes posting a photo to his blog as easy as tap-snap-annotate-post.

Last night we took this for a ride on a walk around Charlottetown, with Oliver taking pictures of “new” things (Berry Healthy, the new Starbucks on Queen Street, etc.). He jacked into the wifi hotspot on my Firefox OS phone to upload them to the Internet, and so it was almost “live photoblogging” in action. You can see the results here.

Now that all the adults have stopped blogging, perhaps it’s time for the kids to take over?

If I am swearing an oath on Prince Edward Island, is it necessary for me to kiss the Bible?

Who among us has not wondered this!

The Affidavits Acts jumps up to answer (emphasis mine):

Whenever any person is required to take, or is desirous of taking an oath in any court, or of making an affidavit for use in any court, or in any proceeding or matter when an oath is required to be taken or administered, it shall not be necessary to kiss the Book containing the Gospels, it shall be sufficient for the party to place his hand upon the Bible, declaring his intention to tell the truth, and such declaration shall have the same force and effect as if such person had kissed the said Book.

I’ve been waiting for years to have an incident arise that would require me to learn more about the Prothonotary of Prince Edward Island; today was the day. Speaking of which, if I ever get married I am so having the Prothonotary perform the marriage.

Harry Truman, by the way, was the last President of the United States to kiss the Bible at his inauguration.

(And, finally, you’re probably wondering: why is he capitlizing the word Bible? This appears to be the tradition.)

I am

I am