The Wikipedia entry for Arthur Murray was started a decade ago on July 6, 2003. On that first version of the entry Murray’s birthplace is listed as New York, New York (emphasis mine):

Arthur Murray (April 4, 1895 - March 3, 1991), a famous dance instructor and businessman, was born in New York, New York as Moses Teichman.

His birthplace in Wikipedia remains New York right up until the version of June 13, 2007:

Arthur Murray was born in New York City in 1895 as Moses Teichman.

Six days later, on June 19, 2007 there was an anonymous edit to the page that changed his birthplace to Galicia:

Arthur Murray was born in Galicia, Poland (at the time it was part of Austria-Hungary) in 1895 as Moses Teichman or Teichmann.

Two years later, in the version of June 26, 2009, this got even more specific with the addition of a sidebar that listed his birthplace as “Todhajca, Kingdom of Galicia, Austro-Hungarian Empire”.

This was updated on November 1, 2010 to “Podhajce, Kingdom of Galicia, Austro-Hungarian Empire”, a village that happens to be 100 km from Serafyntsi where my great-grandfather was born two years before him.

His birthplace in Wikipedia has been listed as Podhajce ever since.

What do other sources say?

- Biography.com: New York, New York.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: New York, New York

- New York Times obituary: “a native New Yorker”

- Washington Post obituary: New York

- USA Today obituary: “New York’s Lower East Side”

- IMDB: New York City, New York

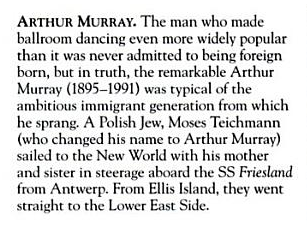

Because the Wikipedia edits that changed the birthplace to Galicia were anonymous and without sources, it’s impossible to know whether they are accurate, and there’s certainly evidence from multiple obituaries and well-accepted sources to suggest that his birthplace was New York and not Galicia. But there’s also evidence to the contrary that supports his being foreign-born.

For example, there’s a passenger record in the Ellis Island collection for “Moses Teichman” (Murray’s name at birth) that’s a close match for his circumstances (and perhaps the source for the Wikipedia?):

First Name: Moses Last Name: Teichmann Ethnicity: Galicia, Galician Last Place of Residence: Todhajca Date of Arrival: Aug 31, 1897 Age at Arrival: 1y Gender: M Marital Status: S Ship of Travel: Friesland Port of Departure: Antwerp Manifest Line Number: 0019

This record is featured on the Ellis Island “Famous Ellis Island and Port of New York Arrivals” page.

There’s this passage in the the book Ellis Island’s Famous Immigrants:

So where was Arthur Murray born? Who knows. The sources-of-record say one thing, the crowd, and some others, say another.

This is an example either of Wikipedia’s virtues in exposing accurate information where others fail, or in Wikipedia’s failure to properly source and credit facts, depending on your point of view. If nothing else it’s a demonstration of why we need to teach our children to use the “History” feature of Wikipedia to understand the provenance of the “facts” they find there.

As I was rolling across Nova Scotia on the weekend I was listening to a late June episode of Radiolab.

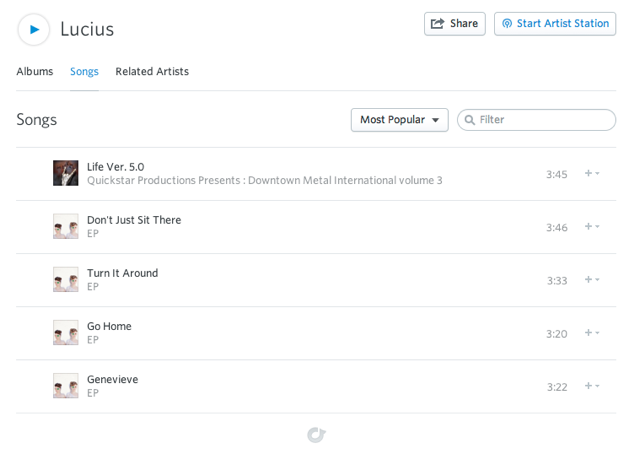

Buried deep inside that episodette you’ll find a song by the Brooklyn band called Lucius. I liked what I heard and so when I got back to Charlottetown I fired up the Rdio and looked them up:

I pressed “play” and out of my headphones came this.

Was this the same band?

The band that Seventeen magazine called “two indie darlings”?

Well, no.

It seems there are two bands called Lucius: the indie darlings from Brooklyn and the Norrköping, Sweden band in the video above, a band that plays, it is said, “today’s best aggressive metal.”

Perhaps music needs to adopt the same conventions as acting and have Professional Name Protection for bands? This would prevent those looking for careful, gentle music from finding violent attack music (and vice versa).

If you’re still in shock from having pressed play on the Swedish aggressive metal, here’s an antidote.

My cousin Sergey was arriving at the airport in Halifax after a few weeks away, and I volunteered to drive over and pick him up.

As an adherent of the religion of “why make a simple trip when you can make a complicated one,” I decided to drive to Halifax via Cape Breton, stopping for lunch on Isle Madame with my old friend George.

I headed off at the crack of dawn on Friday morning toward the Wood Islands Ferry, reservation in hand and convinced that there would be hundreds of cars in line. There were a dozen cars in line. And so I spent 45 minutes in the cool early morning sunshine at the ferry terminal before boarding the ferry and after boarding almost had the cafeteria to myself.

The drive from Caribou to Isle Madame, which seemed like it should take forever, did not take forever, and I was there for 11:30 a.m. and enjoying a tasty lunch by noon. After a pleasant afternoon rambling about the isle, I set off for Halifax at 7:00 p.m., stopping for a moribund supper at “Sense of Japan” in Antigonish (I had such high hopes). I arrived at the Halifax Marriott around 11:30 p.m. and checked into my wasn’t-that-a-deal $75 Priceline room and fell immediately to sleep.

Sergey wasn’t due to arrive at the Halifax airport until 6:00 p.m. so I had the day to myself in the city; here are the highlights:

- The Marriott was rather nice. I was asleep most of the time, but the bed was comfortable, the room was clean and the shower was powerful. There was also a copy of the Globe at my door. Usually when I blindly book a “4-star hotel with pool” in Halifax I end up at the Westin, that tired old beast of a hotel at the other end of downtown; this was a much nicer alternative (though it suffers from the “add $20 to your bill per day because you’ve got to park somewhere” problem that all downtown Halifax hotels suffer from, the Westin included).

- There’s a new branch of Two if By Sea in the Historic Properties (new to me: perhaps it’s been there for years and I haven’t noticed). I suspect this is the branch where employees from the home office in Dartmouth are sent for punishment, as it had nowhere near the aesthetics of the original, and it would appear, from the brief time I was there, that staff spend their days explaining what an espresso is to confused and hot tourists. Nonetheless, they made me a nice cup of coffee and served me a nice blueberry muffin. And given that it’s right beside the Marriott, the location can’t be beat.

- Strange Adventures has moved into a new space at 5110 Prince Street, a space occupied, several occupancies ago, by Charlottetown’s own “Cool as a Moose.” The move has been transformative: whatever the attractions of the old subterranean hovel up the hill, I was always wary of bumping my head and couldn’t shake the persistent claustrophobia. The new space is bright and roomy and the staff seem 200% happier and 300% more helpful. I bought a copy of the new Lucy Knisley book, a copy of The Cartoon Introduction to Statistics and a nice little tract on coffee brewing.

- I’m a recent convert to the “sling” style backpack: I received a simple one as a gift for judging the Heritage Fair this year and have loved it but decided I needed something with more nooks and crannies so I dropped in at MEC and bought a Pod Sling Pack which I’ve been trying out in the field ever since. It’s lightweight but well-padded, has two spacious pockets (enough to carry all three Strange Adventures purchases plus two bike lights I purchased at the same time) and it was only $24. Watch for it slung around me as I make my way around town.

- One doesn’t want to look a gift bánh mì in the mouth, but the oomph seems to have been drained from the bánh mì at Indochine in the Lord Nelson Hotel annex. It wasn’t that it was bad, it’s jus that it wasn’t as life-affirming as the one I had last year. I don’t unrecommend the place, but I rescind my wholehearted blessing.

- Cantina Mexicana, across the hall from Indochine, looked so promising with its “no freezers, no microwaves, no deep frying” advertising on the sandwich board, but it turned out to be no more than a Subway with tortillas, and supper there was uninspiring. Perhaps if I spent some time getting to know and understand their ingredient mix I could end up with a better result, but why wouldn’t I just make tacos at home then?

- The Just Us Café on Barrington has moved across the street and, like Strange Adventures, has discovered the joys of whitespace; I grabbed an iced tea there midday to keep out of the punishing heat and it was well-made and the space was nice to hang out in.

- Later in the afternoon I had a very pleasant coffee with Gordie at Steve-o-renos and an absolutely horrible, horrible, horrible coffee at the Second Cup later in the day (when all the places serving coffee fit for humans were closed).

- Sergey’s plane was delayed by 3 hours, which opened a window for me to see Before Midnight, the third installment of the every-9-years Ethan Hawke-Julie Delpy series. It was playing at the Oxford, Halifax’s only bona fide cinema, a cinema that, being bona fide and all, lacks air conditioning. And thus clientele for a 4:00 p.m. showing on a day when it was 35ºC in the shade. So I saw the movie with a crowd of about 5 other people and it’s a testament to how absolutely fabulous the movie is that I thoroughly enjoyed all two hours of the experience. I will leave it to others more eloquent than me to review the movie; suffice to say that if you enjoyed No. 1 and No. 2 you will enjoy No. 3.

At 7:30 p.m. I drove out to the airport, waited an hour while customs dealt with two planeloads of arriving Europeans, and by 9:00 p.m. we were speeding home, wary of the moose, to the Island. We pulled into our driveway at midnight. A nice short action-packed summer vacation.

There’s a lot to like about HERE Maps (née Ovi Maps, née Nokia Maps), especially, for my purposes, that it runs very well on Firefox OS mobile devices – indeed Mozilla is promoting it as the “maps” application for Firefox OS.

Last year when Nokia finally spun down Plazes, it helpfully offered an option to we olde Plazes users to take our saved collections of “Plazes” – locations we’d checked into – and import them into HERE Maps as points of interest. I did this, and as a result ended up with 802 “unsorted items” my HERE Maps “Collections” section:

Initially this was just an irritant; when I started to use HERE on my Firefox OS phone it became a liability, because opening the “Collections” tab on the device took an awfully long time (in theory because the device had to grab the details of those 802 unsorted items).

I tried to resolve this with some helpful Nokia engineers, but eventually their patience ran out and I was left to my own. Fortunately I managed to figure out a relatively easy – if hacky – way of making this happen.

Here’s what I did.

I logged into here.com with my Nokia account – the account with all those pesky “unsorted items”. Then, using the Firefox Web Developer tool I watched the “Network” tab as I deleted one of the items; it called this URL:

http://here.com/collectionsBackend/favourites/favoritePlace/fb75b689-2ab5-4ff4-9b7a-03798b4540ae

I reasoned that the “fb75b689-2ab5-4ff4-9b7a-03798b4540ae” was a unique ID for the item, and so set about finding a list of all of the IDs of the “unsorted items” attached to my account.

Again using the Web Developer “Network” tab, I was able to determine that the HERE website pulls a JSON representation of all of my Collections, which includes the “unsorted items” as well as items that I’d placed inside named collections, from:

http://here.com/collectionsBackend/all?skiplastsync=false&skipfavourites=false&skipcollections=false

This JSON looks like this:

{

"favourites": {

"total": 802,

"startIndex": 0,

"data": [

{

"type": "favoritePlace",

"id": "938e7f3d-fca6-48b6-848c-864afc27627e",

"deleted": false,

"collectionId": [ ],

"name": "Aqua Bistro",

"creatorId": "9f95b738-772b-4862-bb3a-9b17865d665f",

"createdTime": 1336568888931,

"updatedTime": 1337712464859,

"location": {

"position": {

"longitude": -71.950513100715,

"latitude": 42.8771882289749

}

}

},

{

"type": "favoritePlace",

"id": "ee51605b-7829-438a-b2e7-7ae9c64cbc0f",

"deleted": false,

"collectionId": [ ],

"name": "Arken",

"creatorId": "9f95b738-772b-4862-bb3a-9b17865d665f",

"createdTime": 1336568893409,

"updatedTime": 1337712495800,

"location": {

"position": {

"longitude": 12.3842807492963,

"latitude": 55.606174327026

}

}

},

And continued on through all 802 former-Plazes and a handful of other items I’d saved inside HERE. The key here was to extract the “id” of each item. To do this I just copied a text file, used grep to filter for lines with “id”: and then used BBEdit search-and-replace to turn each line into an API call to delete the item.

Now I had a text file with a whole bunch of URLs to hit with an HTTP DELETE request; the final piece of the puzzle was to figure out how to hit this while authenticated to my account. This turned out to be easy: I just used the Web Developer tool to examine the DELETE request that Firefox sent, and then copied the cookie key-value pairs it sent along with the request into the cURL equivalent. What I ended up with was whole bunch of cURL commands, each of which looked like this:

curl -X DELETE \ -b "undefined_s=First+Visit; OviAPICaller:3548978; ... " \ http://here.com/collectionsBackend/favourites/favoritePlace/442bd...

the second line contained each of the cookies I pulled from Firefox, in the format “NAME1=VALUE1; NAME2=VALUE2…”.

With thls in place, I saved the text file with the cURL requests and ran it from the command line on my Mac:

sh delete-here-places.sh

The script stopped unexpectedly after deleting about 400 items (error message “Sorry, there’s a problem on our end.”), but when I ran it again it continued.

The result no “unsorted items” in HERE Maps, confirmed by looking at the JSON:

{

"favourites": {

"total": 0,

"startIndex": 0,

"data": [ ],

"count": 0

},

One important thing to note: if you do what I did, you’ll delete all of the “favourites” you’ve saved in HERE, ones you imported from Plazes and ones you save in HERE itself; beware.

Isn’t the open web great!

I’ve been a member of the home and school association at Prince Street School since my son Oliver started there six years ago. Oliver’s moving on to intermediate school in the fall, and I’d been searching a way of marking the end of his time at the school; when I heard Mark Leggott sing the praises of the library’s Espresso Book Machine as a community resource at a conference session in May, I decided that “making a book” seemed like a good project to take on.

Literacy is important at any elementary school; there’s a particular focus on literacy at Prince Street, and the school holds a “Young Author’s Night” to celebrate student writing every May; every grade 6 student prepared a piece of work for that night, and, upon hearing of my idea, the school’s two grade 6 teachers, Jo-Anne Parsons and John Macfarlane reasoned that those pieces of writing would make good material to assemble into a book.

Robertson Library’s Espresso Book Machine is an amazing piece of technology: you send it a PDF of the insides of a book and a second PDF of the cover and it spits out bound paperback books that look, well, just like bound paperback books. The machine is available to any individual or group on Prince Edward Island who wants to publish a book; it’s not difficult to do, and I thought I’d outline the process I went through so that others can follow, especially others who want to assemble student writing into a book.

Getting the Writing

The plan was to set aside a single page of the book for a piece from each student. The writing was already typed into a word processor – Microsoft Word on the computers in the school’s lab, stored in the individual students’ personal account.

For John’s class, the technology coordinator at the school, Philip Brown, had the smart idea to use the opportunity to teach the students how to send an email with an attachment to me; as a result I ended up with 17 email messages in my inbox one day, one from each student in John’s students.

For Jo-Anne’s class I received a single Word document with all of her students’ writing, directly from her by email.

I double- and triple-checked the documents to make sure I had something from every student, and asked Philip to double-check every name for spelling.

Assembling a Book

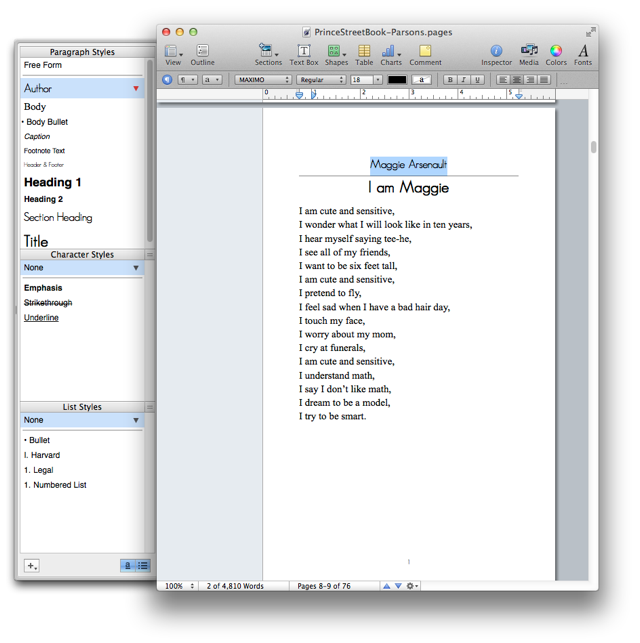

I use the Mac OS X Pages word processor every day, so I decided it was the tool I would use to make the book.

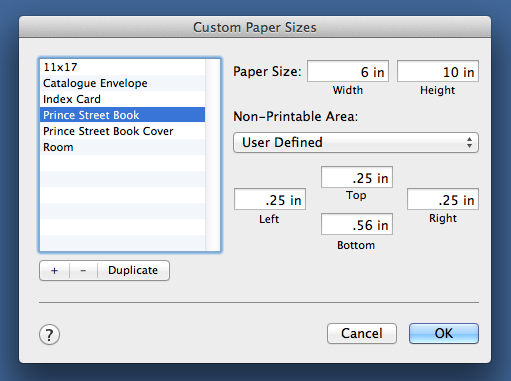

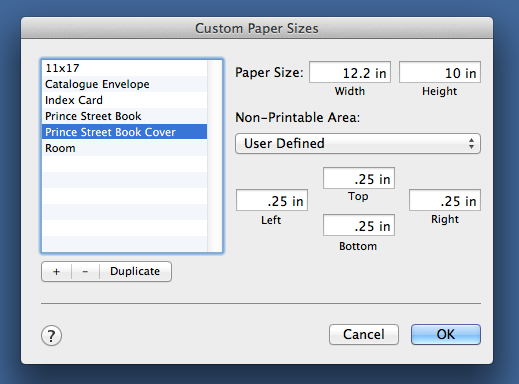

I like books that are tall and narrow, so after playing with some different sizes I decided on 6”x10” for this book (the Espresso Book Machine will print books as small as 4½”x5” and as large as 8¼”x10½”). So to start I set up a custom page size in Pages (File | Page Setup | Paper Size | Manage Custom Sizes) of 6”x10”:

I then opened each of the Word files I received and cut-and-pasted the text into a new Pages document, removing any formatting in the process (Edit | Paste and Match Style) and inserting a page break at the end of each piece.

I then created “styles” in Pages for the author’s name (“Author”), for the title of the piece (“Title”), and for the body text (“Body”) and went through the document highlighting text and assigning styles as needed:

It became apparent that the plan of “one page per student” wasn’t going to work out: some of the pieces were only a paragraph, some were 5 or 6 paragraphs. It turns out, however, that a technical requirement solved this problem for me: the Espresso Book Machine needs books to be 80 pages at minimum, and so I needed to make the book “thicker” and I did this by assigning two pages per student, a right-facing one to start and then, if needed, continuing onto the next left-facing page:

This format made for a nice 76-page book, which was close enough to 80 pages to make it workable for the machine.

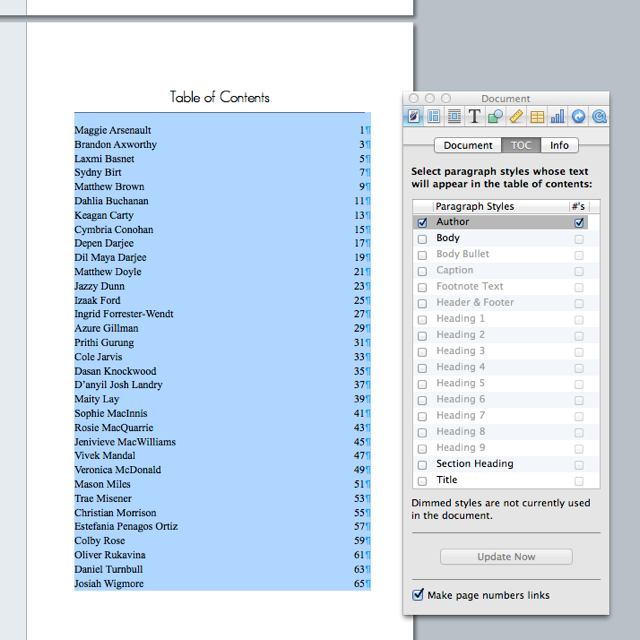

I decided to organize the book by alphabetical last name of students so, with some additional cutting-and-pasting, rearranged the pieces into this order. I then decided that it would be nice to have a table of contents, so I used the “Table of Contents” feature on Pages (Insert | Table of Contents) to do this, setting the “Author” style that I’d already used for formaating to be the paragraph style that defined a table of contents item:

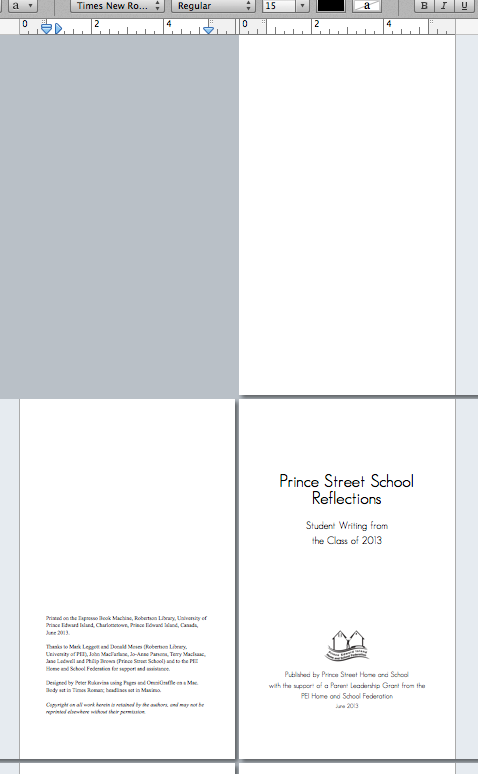

Finally I created the introductory pages of the book, starting with a blank right-facing page, then a “thank you” page with credits, and finally a “title” page:

Making a Cover

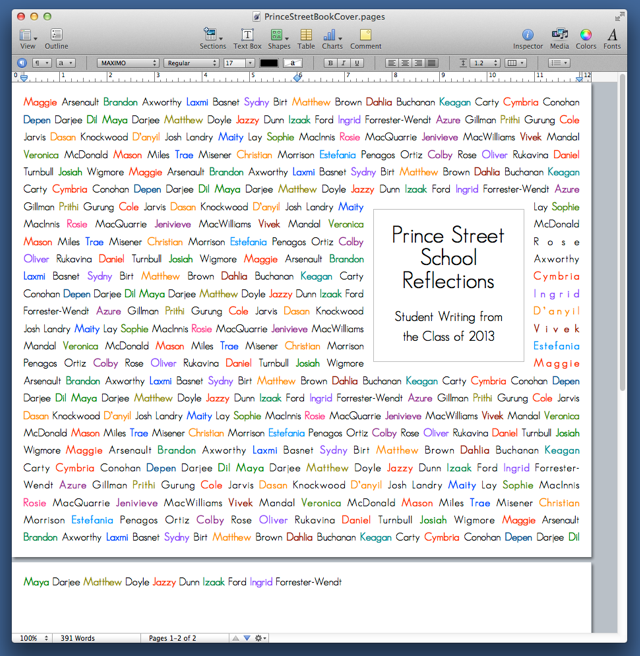

My original thought was to use something photographic for the cover (the Espresso Book Machine can print black and white on the inside and full colour for the cover), but I was too late to have time to assemble photos of all the students, didn’t have a good photo of the school itself, and nothing else presenting itself, so I decided to use the students’ names as the cover.

The helpful Creating an EBM Ready PDF prepared by the library has a formula for determing the size of the cover. My book was 6”x10”, so to begin with the cover (back plus front) would be 12”x10”, but there needs to be an allowance for the spine, and this depends on the number of pages and the thickness of the paper. In my case the calculation went like this:

76 pages ÷ 377.3585 = 0.2014 inches

I opened a new Pages document and created a second custom paper size of 12.2014”x10” for the cover:

I copied the names of the students from the table of contents in the book into the cover document, removed all of the carriage returns, and then set each student’s last name in a different colour, choosen at random. And then copied-and-pasted the names until they filled up the page and inserted a text box (Insert | Text Box) for the title:

I made sure that the title box was centred inside the right-hand 6 inches of the front cover so that when the book was printed it would be centred.

The names ran over to a second page, but that was fine as when I printed the cover to a PDF I just limited the printing to the first page (having them run over meant that the last line, ending with Dil, was fully justified).

Printing the Book

With the inside and the outside of the book in Pages my final step was to print to a PDF (File | Print | Save as PDF). There was nothing special that I needed to do when I did this; it was just a regular old PDF.

I emailed the two PDF files up to Robertson Library, and the next day was alerted that the was a proof copy of the book ready for me to take a look at. I jumped on my bicycle and was there 30 minutes later, eager to see what the final product look like.

Here’s what the book looks like coming out of the Espresso Book Machine:

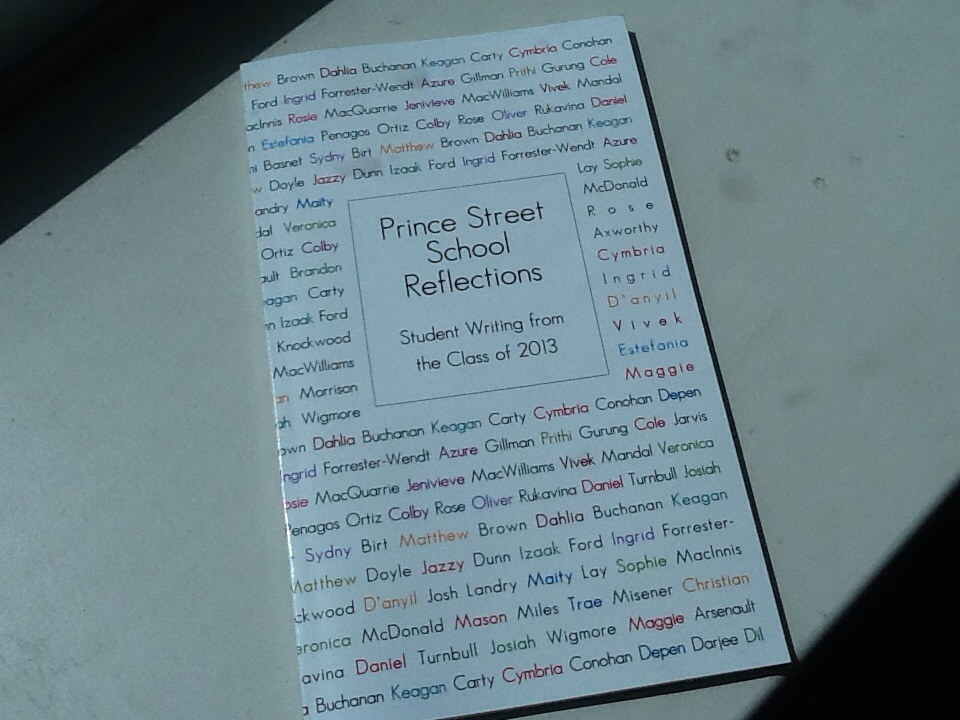

And here’s what the printed book looks like:

I read through the proof carefully, didn’t find anything that needed changing, so gave the go-ahead to print 50 copies of the book. By the end of the week they were ready and so I drove up to Robertson Library on Monday morning and picked them up and dropped copies off at the school for distribution – on the second last day of school, as it turned out.

Reaction from the Students and Teachers

I wasn’t at the school when the books were distributed, but fortunately CBC’s Island Morning radio programme sent a reporter up to the school to interview Jo-Anne Parsons and some of her students; I think the piece captures the reaction well, and listening to it made me feel happy that we’d done it.

Distribution of the Book

It was important to me, and to the teachers, that book be available not only to the students – who each received a copy to take home, for free – but also that the book enter the collections of the school, public and university libraries, so copies were sent to each and they’ll be catalogued and available to the public.

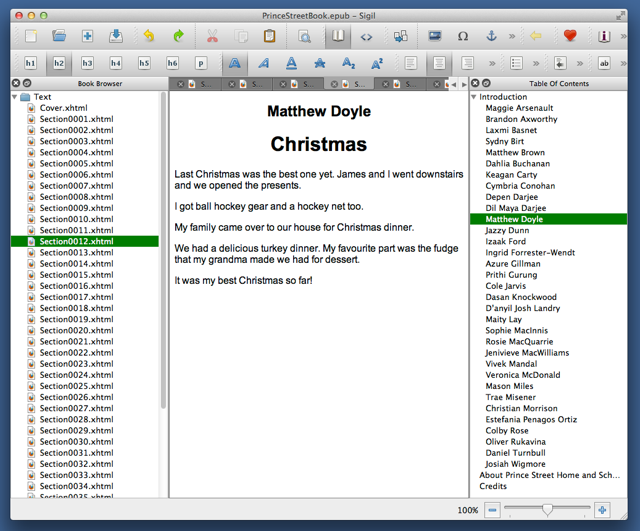

I also uploaded the book to the Internet Archive for preservation, both as a PDF (the same PDF that was printed), and as an ePub-formatted ebook.

I created using the ePub version of the book with the Sigil open source ePub editor); I’d originally tried Pages’ own “Export as ePub” function, but I found that this resulted in an ePub that was too heavily-formatted to be useful on ereaders, so I started from scratch in Sigil, exporting the text from Pages as “Plain Text” and then cutting and pasting into Sigil with one ePub “section” for each piece. When it was done, it looked like this:

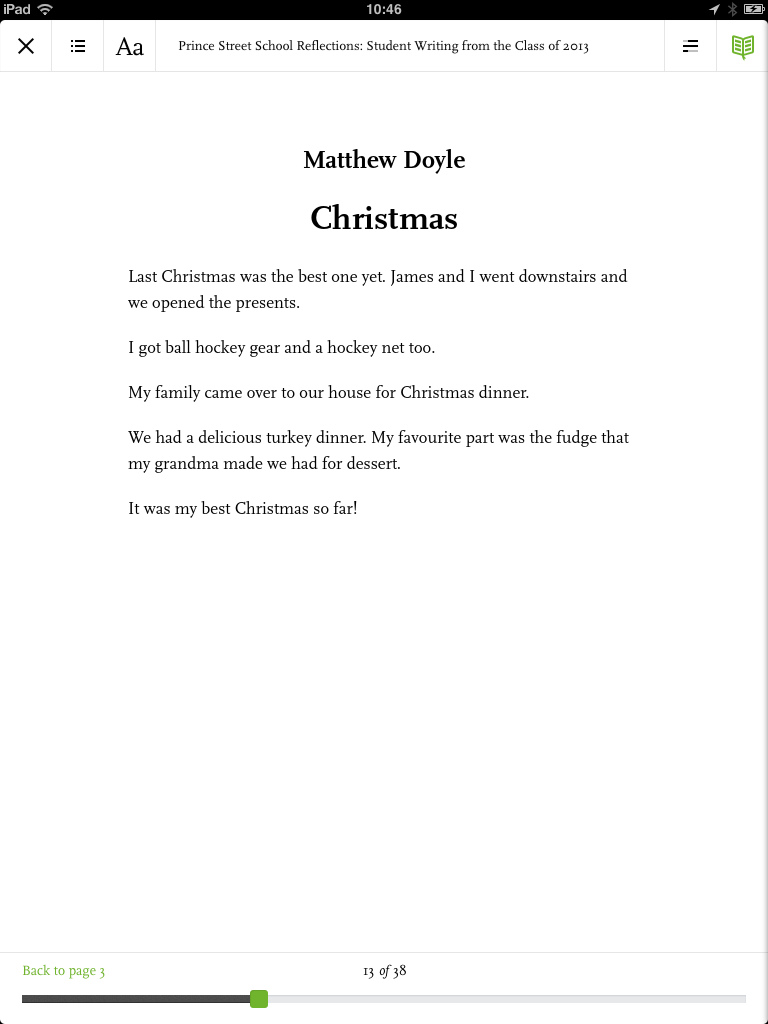

And in Readmill the ePub is quite readable:

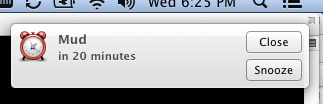

This popped up on my Macbook Air’s screen a moment ago:

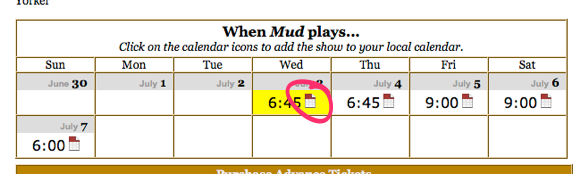

It appeared there because I finally got around to adding a feature to the City Cinema website that I’ve been meaning to add for years: for any film on the calendar you can now click a handy link and add that day’s show of that film to your local calendar (technically it sends you an iCalendar format; on a Mac this will just magically load into iCal; not sure what it does for Windows or Linux).

So when you’re looking at a film’s details, like Mud you will see tiny calendar icons beside each time on the calendar; click them to experience the magic:

I expect this tiny update to increase my City Cinema attendance by 200%.

Remember the Evans McKeil, the tug that visited Charlottetown Harbour last week? Well I noticed last night that she was back, and I decided that I couldn’t let this second visit pass without going down to the Port of Charlottetown to take a look up close. After all, had my father had his way, I would have once worked for McKeil Marine and the tug might have been my workplace.

Regular readers may recall that Catherine, having grown up on a farm, is the most trespassing-averse person you’ll ever meet. She simply won’t trespass, or even engage in anything which has the slightest whiff of trespassing. Fortunately, Catherine is 1,500 km away as I type, visiting family in Ontario. Although her trespass-averse ways have infected me, there lurks inside me the kernel of a trespasser, and it was that kernel that I called upon to allow me to breach the tight security at the port.

As it turns out, all those “RESTRICTED AREA: Authorized Persons Only Beyond This Point” signs that greet you at the end of the wharf appear, at least on Canada Day, to be security theatre. After cycling through the (wide-open) front gate, I dutifully knocked on the door of the “Port Security” shed, thinking that I should at least check in.

But there was nobody home.

I cycled to the end of the cruise ship side of the wharf but was greeted by 12’ high fencing that extended out over the water (apparently keeping cruise ship passengers penned-in is the highest priority of the port).

On my way back I noticed that the high security fencing separating the cruise ship side of the wharf from the working wharf had a convenient passageway in it at the end, just the size of a stout middle-aged man riding a bicycle.

I pedalled my way through, and, shortly thereafter, was standing in front of the Evans McKeil, perched with her bow abutting a football-field-long gravel barge that she’d nudged here from Nova Scotia.

It bears mentioning at this point that I have an almost-pathological fear of burly working men. This is why Catherine handles relationships with the trades in our household, and it’s likely the aspect of my personality that my father though might get toughened out of me if I went to work on a tugboat when I was 16.

So introducing myself to the crew of a gravel-barge-pushing tugboat – perhaps the burliest of burly working men – is not in my nature. But now was not the time to be a shrinking violet.

“Hello there,” I yelled down to the crew, a group of 3 or 4 men gathered in the stern.

“Happy Canada Day!” they yelled back. “You’re not the guy who’s bringing us beer are you,” one of the crew joked.

“Sorry, no,” I replied. “I’ll see what I can do, though,” I joked back.

“Is this the Evans McKeil that was built in 1936?”, I asked.

“She is,” an orange-suited crewman replied. “She’s riveted together,” he said proudly as he pointed out the rivets in her hull, “made before welding.”

“She’s beautiful,” I said.

They nodded.

“Have a good holiday,” I yelled down as I pedalled off.

“You too,” they replied.

Now I may have a pathological fear of tug boat crewmen, but I also know that if a tugboat crew jokes about beer, they’re probably thirsty for beer. And it’s Canada Day. And they’re stuck on a 77-year-old tugboat behind hundreds of tonnes of gravel.

It was time to spring into action.

Fortunately the recent liberalzation of liquor laws here in Prince Edward Island means that the liquor stores are open on holidays like today. I pedalled up to the Queen Street store, made my way to the cold beer cooler (reasoning that cool beer rather than warm beer is best to ward off the taste of gravel barge in your mouth), and picked up a 12-pack of made-in-PEI Beach Chair Lager (my choice made both in support of a PEI brewery and also because their 12-pack of cans seemed like it would fit in the carrier on the side of my bicycle).

I made my way back to the Evans McKeil, once again breaching the stringent security perimeter, and found two of the crew, including the one I’d chatted with, up on the wharf.

“You didn’t think I’d really bring you beer, did you?”, I asked.

They had a puzzled look on their faces.

“Happy Canada Day!”, I said, as I handed over the beer. “My father knew Evans McKeil, and I’m just passing this along.”

Somewhat disbelievingly – who is this strange man on a bicycle bearing gifts of beer, their look said – they thanked me warmly.

I pedalled off into the sunset, safe in the notion that I’d done the right thing, and made a tugboat crew’s hard life just a little easier.

I hope I did my father proud.

Happy Canada Day!

Remember frozen yogurt? It was big in the early 1990s. For a time there it seemed that you couldn’t escape it, whether you were filling up your car with gasoline or buying chicken. I went to the big franchise show in Toronto back then and everywhere you looked it was frozen yogurt franchise opportunities.

And then, mysteriously, it went away.

Even Dairy Queen stopped serving frozen yogurt a few years ago.

But it’s back.

And, as it turns out, I happen to have two friends in the business, running competing frozen yogurt places in Charlottetown mere blocks from each other. Downtown froyo and midtown froyo, you might say.

Downtown it’s Berry Healthy, owned by former provincial government mandarin Chris Leclair and aided by my friend Cynthia King. Located on Kent Street in the old Captain Submarine space on the first floor of the Royal Trust Tower beside the police station, it opened this weekend and I’ve just returned from my first visit.

Downtown it’s Berry Healthy, owned by former provincial government mandarin Chris Leclair and aided by my friend Cynthia King. Located on Kent Street in the old Captain Submarine space on the first floor of the Royal Trust Tower beside the police station, it opened this weekend and I’ve just returned from my first visit.

Inside it’s all hypergreen and hyperpink, mirroring the colours on the logo. The interior architecture was by N46, the interior design by Ottoman Empire, and the graphic design was by Kate Westphal (who I worked with many years ago at the Anne of Green Gables Store where, among other things, she designed the labels for a line of preserves that I sourced; she’s very talented).

The format is much as you’ll encounter in any latter-day frozen yogurt place: a bank of machines, each dispensing two flavours with the capability of swirling the two together. You serve yourself and then move on to a “toppings bar” filled with all manner of things, from crushed Skor bars to (as the name would seem to demand) blueberries, pineapple and kiwis. It’s sold by weight, so to pay you place your cup on a scale and you pay by the ounce.

Blocks away, at the University Avenue end of the Holiday Island Motor Inn, is “midtown froyo,” Islands Frozen Yogurt Bar, the new Charlottetown branch of a shop that opened last year on the main intersection in Cavendish.

Blocks away, at the University Avenue end of the Holiday Island Motor Inn, is “midtown froyo,” Islands Frozen Yogurt Bar, the new Charlottetown branch of a shop that opened last year on the main intersection in Cavendish.

Islands is run by my friend Linda Lowther and her family (Linda herself is a former provincial government mandarin), and while I have yet to visit, I understand the format is in the same mold: squirt yourself some yogurt, lavish on the toppings, pay by weight.

The palette at Islands is also rich, albeit not so “hit you over the head with a colour hammer” as Berry Healthy; a pale blue accented with a vibrant orange.

And so, where you’d be hard-pressed to get a cup of frozen yogurt in Charlottetown last summer, this summer we’ve got our very own frozen yogurt showdown happening.

Both shops opened this weekend.

Both are running promotions (Islands is giving away 1000 bowls of yogurt, Berry Healthy is handing out discount cards that give you your first 5 oz. for free).

And both are promoting themselves on Facebook (as of this writing Berry Healthy has a slight “likes” edge, with 719 likes to Islands’ 658 likes) and Twitter (@berryhealthypei vs. @islandfroyo).

It’s like 1998 all over again – the year Deep Impact vs. Armageddon both asteroids-vs-Earth movies, opened the same summer – but more local and more frozen.

Fortunately, as anyone in the more-than-a-dozen coffee shops that have opened in the last 20 years can tell you, competition can grow the market, and so we might find ourselves with a burgeoning longterm frozen yogurt duopoly in the city.

Or we might mysteriously all lose our taste for frozen yogurt, as we did the first time around, and move on to kale frappes or icy pickles or marmalade taffee or whatever the next dessert trend to come along is.

In the meantime, enjoy your embarrassment of Skor-bar-sprinking opportunities, Charlottetowners.

And best wishes to my friends Linda and Cynthia as they square off, froyo vs. froyo, in friendly frozen competition.

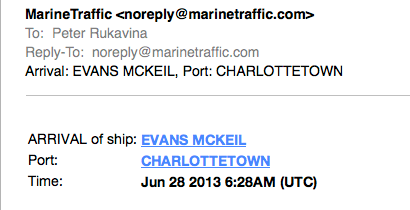

I have a MarineTraffic.com alert set up to let me know when vessels arrive and depart Charlottetown Harbour; early Friday morning one of these alerts landed in my email:

Not so remarkable, perhaps: it’s shipping season and with oil delivery and pleasure craft and cruise ships I get several alerts like this a week. But this one was different: I recognized the name “Evans McKeil.”

My father spent much of his career studying the nearshore area of the Great Lakes and this meant that he spent a lot of time on and around boats. By virtue of this he knew Evans McKeil the man and his company, McKeil Marine. A 1996 article in the Hamilton Spectator describes McKeil’s early life:

Boats have been Evans McKeil’s life since he was a youngster in Pugwash, Nova Scotia.

In the 1930s, Mr. McKeil watched fishing boats head out to sea from the port of 600 souls.

His uncles sailed cargo-laden schooners across the Bay of Fundy to St. John, New Brunswick.

And following World War II, a teenaged Mr. McKeil helped his father, lumber mill owner William McKeil, build a few boats.

At one point when I was a teenager my father suggested the I look for a summer job with McKeil; I think the idea was that this would toughen me up and perhaps teach me how to drink beer. I went to work for Canadian Tire instead and as a result missed out on a career on the water (and never really learned how to drink beer).

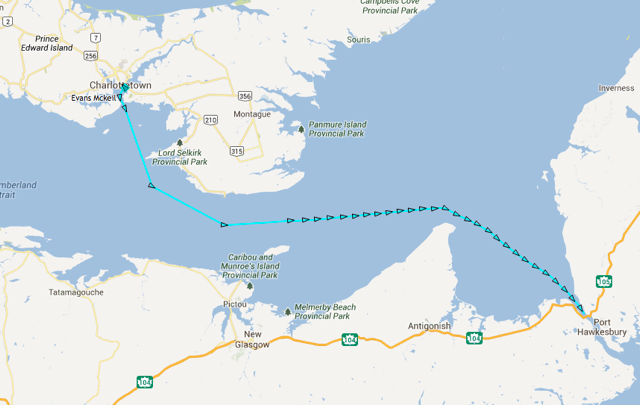

The Evans McKeil that arrived in Charlottetown yesterday morning at 6:28 a.m. UTC is a tugboat. According to information my father passed along, she was built in 1936 and christened “Alhajeula” by the Panama Railway in the construction of the Panama Canal. The tug left Charlottetown yesterday at 23:29 UTC, bound for Nova Scotia. As I write she is making her way through the Canso Strait:

Some might consider it odd that I went to the trouble of setting up an AIS receiver in Charlottetown to monitor port traffic; it’s precisely for stories like this that I did so, though. While not the port it once was, Charlottetown Harbour still plays host to vessels from around the world; every one has a colourful past.

Catherine and Oliver are spending two weeks up in Ontario visiting her family and mine and they took the opportunity to stop over in Ottawa for a couple of days to give Oliver his first opportunity to visit Parliament Hill.

Remembering my own first visit to the Hill in the late 1970s as a high school student, when I was taken for lunch in the Parliamentary Restaurant by my MP, Geoff Scott, I encouraged Catherine to get in touch with the office of our MP, Sean Casey, to see if they could facilitate a tour. They got back to her quickly, and generously offered to meet Catherine and Oliver yesterday morning at 10:30.

Their tour guide was an Islander and long-serving Parliament Hill staffer, Mary Gillis. As it happens, Mary is retiring today, and their tour was her last. All reports are that she was an excellent, thorough guide with a deep knowledge of the Hill.

Mary mentioned to Catherine that she is a sometime-reader of this blog, and so I wanted to take the opportunity to tip my hat to her, both for her service yesterday and for her service to our Members of Parliament over her time there.

I am

I am