Catherine just installed her latest piece – “The Spirit of Charlottetown” – on the back wall of Receiver Coffee in Charlottetown. The piece is a collaboration with glass artist BJ Sandiford; Catherine did the textile work, and BJ the glass. As you can see in the two photos below, the glass is lit up from the back, so the spirit is rather alive.

Nathan Fredrickson made the housing for the piece and Paul Lopes oversaw the installation. Thanks to Chris Francis at Receiver for kindly playing host to the piece, and for his crew for putting up with all the drilling and fussing this afternoon during installation.

My own small role in the install was to set up a WeMo Switch that automatically turns the light on at 7:00 a.m. every morning, and shuts them off at 10:00 p.m. every night. Because the switch allows for remote control over the Internet, one night when I can’t sleep I’ll take myself down the street, phone in hand, and entertain and delight myself by remotely turning it on and off (you can follow along on Twitter).

Catherine has been hard at this for more than a year, as she’s had the opportunity to get into the studio. It’s a masterwork.

Since I joined the Publishing Committee of Island Studies Press I’ve had the opportunity to read many interesting manuscripts. The first of these to come to publication happens to be by my friend John Cousins, and it went on sale for pre-ordering this week.

I recommend you buy a copy: you can do it right now, online.

New London: The Lost Dream is an entertainingly-told tale of the audacious plan to craft a new community on Prince Edward Island’s north shore.

This is not the history of the New London we all know and love, the one with the pottery shop and the L.M. Montgomery Birthplace. It is, rather, the tale of the original settlement of New London, some 10 km away, close to modern day Park Corner and French River, along the length of the Cape Road. What is now a bucolic Island landscape of farms and seashore was once the site of a settlement of industrious new Islanders; that this settlement came, thrived for a time, and then faded away to the point where it appears, surveying the landscape, to never have existed at all, is remarkable.

John’s tale of the rise and fall of this attempt to create a “New London” on the north shore of the Island provides both insights into the history of an area I know and love dearly as well as an education in the political turmoil of pre-Confederation Prince Edward Island.

Did I mention that you should go and pre-order a copy?

My research on the history of time on Prince Edward Island took me to the Government Services Library on Monday.

This little library is one of my favourite branches of the Island’s Public Library Service. It’s tucked away in the basement of the Jones Building in Charlottetown. Woefully, I must report, now behind the iron curtain of security that’s been dropped around public service offices, so you must sign in with photo identification before visiting. But open to the public nonetheless, and staffed by one of the smartest and most helpful librarians you’ll ever meet, Nichola Cleaveland.

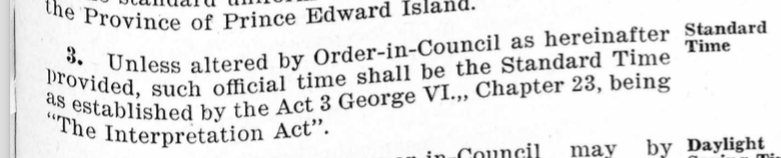

My reason for visiting was to seek help parsing this reference, in the 1947 An Act to Provide for Uniformity of Time Throughout the Province, to Act 3 George VI., Chapter 23:

The first thing I learned was that it’s helpful to know the dates of the reigns of British monarchs if you’re looking for historical laws of Prince Edward Island, for the 3 George VI means “the third year of the reign of George the Sixth.”

These years are called the regnal years, and they run from the date of coronation. George VI became king in December 11, 1936 (when his brother, Edward VIII, abdicated), meaning that his third regnal year – 3 George VI – ran from December 11, 1938 to December 10, 1939.

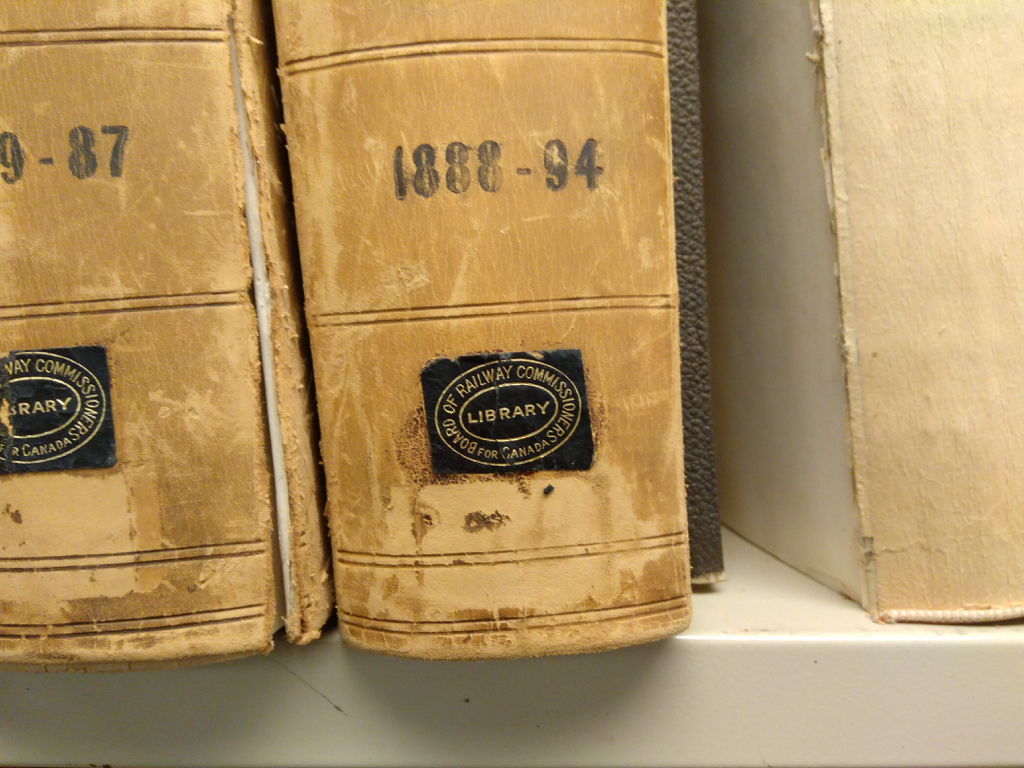

Once you’ve figured this out, then it’s a simple matter of looking for the proper year in the bound volumes of the Laws of Prince Edward Island on the shelf and finding the proper chapter

Here’s the volume, for example, that includes 1888 through 1894 (interestingly, it’s from a set that the Government Services Library inherited from the Library of the Board of Railway Commissioners for Canada when it was deaccessioned):

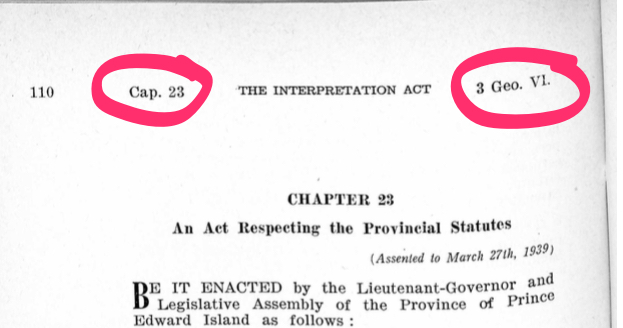

And sure enough, in the 1939 bound volume I turned to Chapter 23 and found An Act Respecting the Provincial Statutes, assented to on March 27, 1939, halfway through the 3rd regnal year of King George VI:

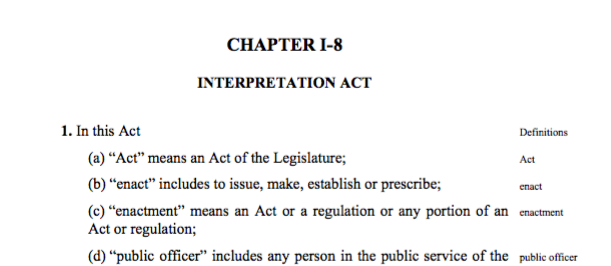

You will find the contemporary Interpretation Act, along with the rest of the laws of Prince Edward Island, online on the Legislative Counsel Office’s website. They no longer make reference to the monarchs in their organizational scheme, alas. The chapters are alphabetical now, so the Interpretation Act is “Chapter I-8”:

This is far less elegant, and requires no knowledge of monarchical history. Which is a shame.

But if they did, you’d be well-positioned if you knew that we’re currently in 65 Elizabeth II. Which is the highest regnal year that’s ever been reached in the British Monarchy.

It is standard practice here on Prince Edward Island for government offices to use special, earlier “summer hours.”

The City of Charlottetown describes its hours as follows:

At its March 2016 Council meeting, Council adopted summer hours of operation for the City’s administrative offices that mirror the hours of operation for the Province of PEI. For the months of June, July, August and September, the summer hours for City of Charlottetown’s administrative offices are: 8 a.m. - 4 p.m.

And the province’s hours, which the City is following on from, are described here as:

Summer hours of 8:00 am to 4:00 pm are now in effect.

Summer hours are determined by Executive Council after consultation with the union.

Here’s the strange thing about summer hours, though: they were put in place as a sort of “mock daylight saving time,” as explained in The Guardian in 1963:

During the past few years, while other provinces were on advance time, this province had a form of Daylight Saving Time, called “advanced summer hours.”

The government took the lead by opening and closing its offices an hour earlier during the six months Daylight Saving Time was in effect in other parts of the country. Most business houses and people throughout the province followed suit and simply put their watches one hour ahead for the six-month period.

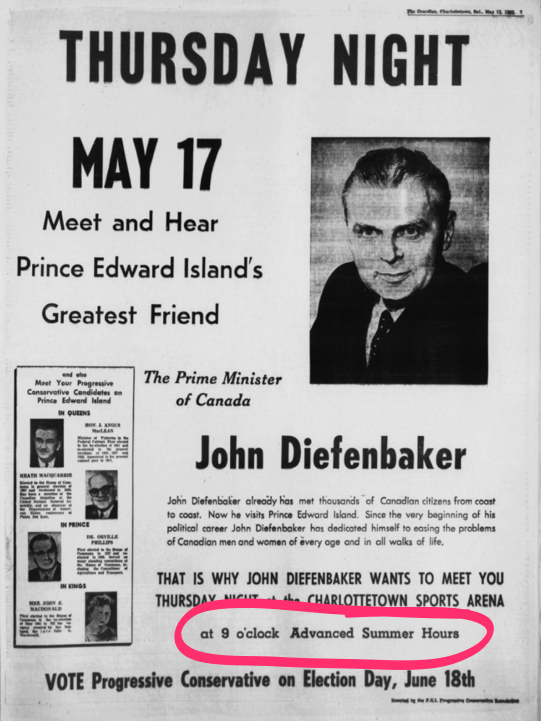

And so when John Diefenbaker visited the Island in May of 1962, his rally in the Charlottetown Sports Arena was scheduled for “9 o’clock Advanced Summer Hours”:

The curious thing is, however, despite the Island officially switching to use Daylight Saving Time in 1963, summer hours remain with us, albeit with only a 30 minute rather than 60 minute change.

This means that a public servant who goes to work for 8:30 a.m. Atlantic Standard Time in March is going to work at 7:30 a.m. Atlantic Standard Time in May, and, when summer hours take effect in June, is going to work at 7:00 a.m. Atlantic Standard Time.

I wonder why.

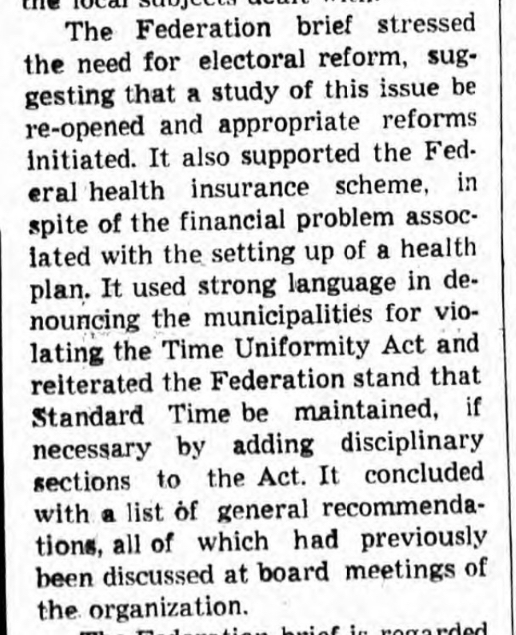

The Guardian reported on March 7, 1956 that the PEI Federation of Agriculture, in its annual report to the Legislature, “used strong language in denouncing the municipalities for violating the Time Uniformity Act and reiterated that Standard Time be maintained, if necessary, by adding disciplinary sections to the Act.”

What was the PEI Federation of Agriculture concerned with?

Daylight Saving Time.

Or what was otherwise known, in the day, as “fast time.”

Earlier in the same edition of The Guardian is the text of the report from the Federation, which did, indeed, use strong language:

The matter which we now wish to discuss is one of a controversial nature and one which has a number of serious an important aspects. The situation existing in the Province last summer after a number of towns went on fast time in defiance of Provincial legislation was most annoying and unsatisfactory to the public generally and to rural people in particular. In our opinion the offending towns acted in contempt of Parliament and their Town Councils set a most unfortunate example of disregard for law and order. This example is difficult to excuse on any grounds, other than possibly that of immaturity of mind which manifested itself in an irresistible desire to play games with the clock.

There are conditions and situations which may at times justify the use of fast time. These conditions quite likely exist in wartime. In peacetime workers in large cities where much time is consumed both morning and evening in going to and returning from work may have a valid claim for consideration. Cities which are located in the Eastern portion of a Time Zone may receive some benefit but we would point out that neither of these conditions exist in this Province and would suggest that our towns are confusing their wants and their needs.

It has been stated that fast time is a convenience to tourists. This we doubt. We do not think that tourist come to this Province to be served with fare which they may obtain in many other places. The Province of Alberta, which has, we believe, a far greater stake in the tourist industry than do we, operates entirely on Mountain Standard Time. Calgary and Edmonton are large cities and are we believe setting a worthy example of cooperating with the general public in a sane and sensible programme of Time Uniformity.

In large areas of the central United States where agriculture is important, there are many cities much larger than even Charlottetown which out of deference to the convenience and wishes of the farming populations maintain standard time.

On numerous occasions we are told by urban people and public men that agriculture is our most important industry and the welfare and convenience of rural people, one of their chief concerns. The Town Councils of this Province know that rural people dislike and are opposed to fast time. They must realize that the present position of agriculture is not an easy one. It should be realized that farm people are facing sufficient difficulties without having this additional one of fast time imposed on them for unnecessary and apparently frivolous reasons.

The people who advocate fast time are not of necessity early risers. Most good farmers are up in the morning at six o’clock. Is it reasonable to expect them to be out of bed at five o’clock? The most ambitious ones turn out at five o’clock standard time, if they are asked to get up at four o’clock, these farmers and the bed will soon become almost complete strangers.

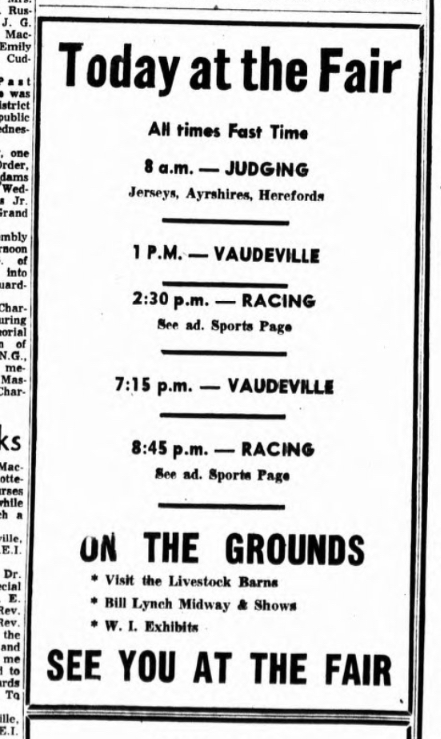

The newspaper report of a recent meeting of the City Council indicated that in the opinion of that body the only unsatisfactory aspect last summer was the lack of uniformity. In other words, the obstinancy of rural people in adhering to the law. In this connection, we would particularly commend the Women’s Institutes which at Exhibition time operated their portion of the fair on standard time and would in addition point out that at district conventions of the Institutes that resolutions were passed condemning fast time.

The press report also suggested that the City Council recognized the unsuitability of fast time in haymaking and that the resolution as worded to avoid this disadvantage. We have heard no explanation of the manner in which haymaking is to be facilitated, other than it might be either completed in June or postponed to October. We would suggest that if the City Council of Charlottetown is sincere in its desire to promote better urban-rural relations that it desist from any efforts to impose either legally or illegally upon the rural people the very doubtful blessing of advanced time.

To summarize may we repeat that rural people dislike fast time. May we emphasize that in their opinion it is a nuisance and an annoyance and a serious handicap in carrying on farming operations. May we also point out that paramount importance of agriculture in this Province and also point out that any towns which do exist here owe their origin and existence to the efforts of agriculture and for this reason have both a business and a moral responsibility to govern themselves at least in part in conformity with the best interest of our most important industry.

There can be no doubt that our rural people will not be satisfied with nor should be expected to be satisfied with anything less than Uniform Atlantic Standard Time throughout the Province. We, therefore, strongly recommend that any changes made in the Time Uniformity Act will be of such a nature as to strengthen the Act and to provide necessary disciplinary sections which may be applied to municipalities whose Councils hold themselves to be, or act in complete disregard of the Legislature.

Mr. Premier and Honourable Members, the farm people of Prince Edward Island are looking to your for relief from the situation which existed last summer. In most cases you have been elected by rural constituencies and rural votes. We have every confidence that their wishes will be your guide in dealing with this question.

Sure enough, if you read The Guardian for the previous year, there’s ample evidence to demonstrate the defiance. While the Women’s Institute may have run its part of the August Old Home Week fair in Charlottetown on Standard Time, as the Federation reported, the fair itself operated on fast time:

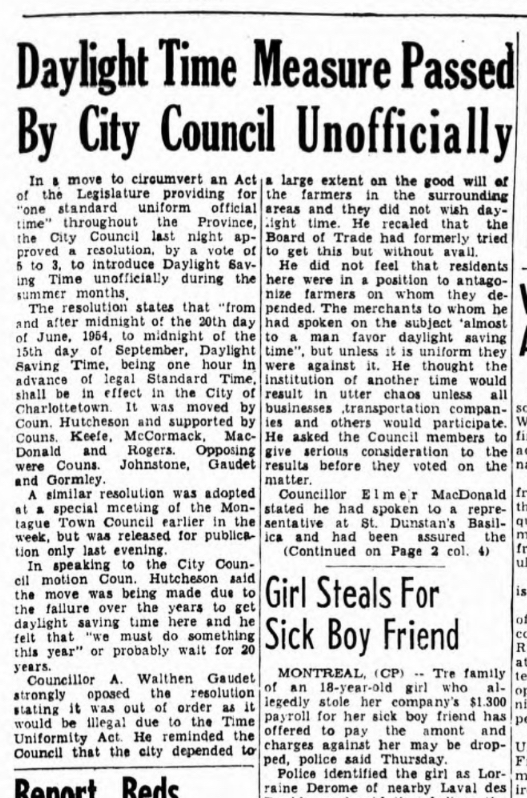

The seeds for all of this were planted two years earlier, when the City of Charlottetown passed a resolution calling for the “unofficial” adoption of daylight time:

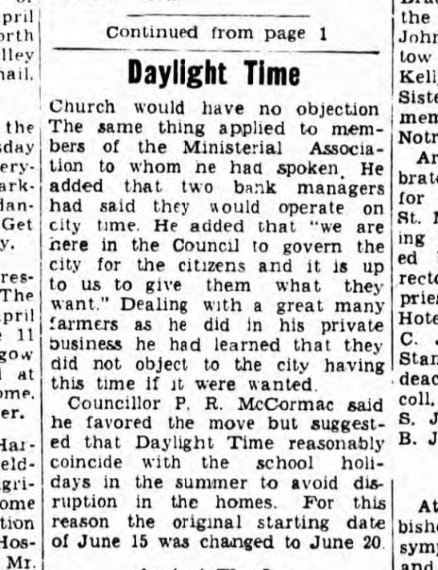

The story continued on the second page, reporting that there was no religious objection to the move, and using the phrase “city time”:

The story finished with the suggestion from Councillor Gaudet that “in flouting the law this Province and city was coming dangerously close to conditions in Germany and Russia,” demonstrating that hyperbole was as alive and well in the council chamber 50 years ago as today.

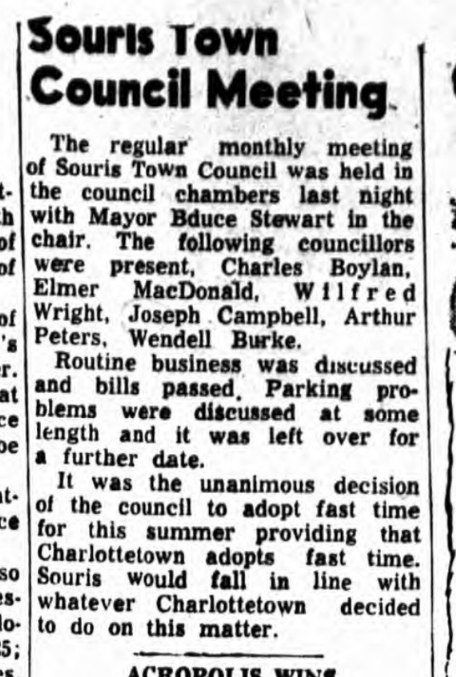

The following spring, on April 19, 1955, The Guardian reported that Souris was set to adopt fast time, but only if Charlottetown repeated the practice it adopted the previous year:

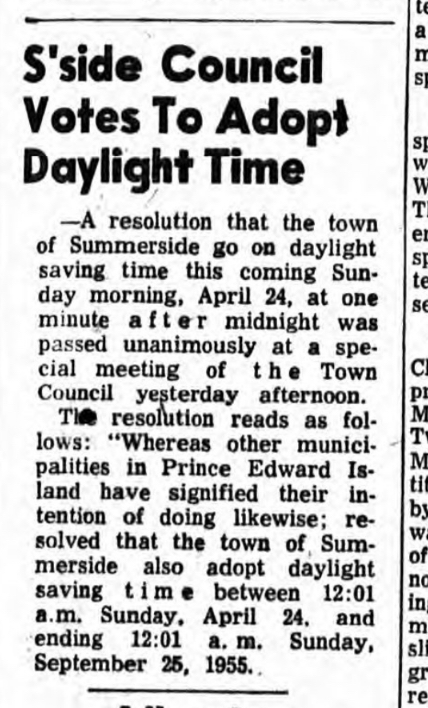

On April 21, 1955 The Guardian reported that Summerside passed a similar resolution, albeit without the Charlottetown-proviso:

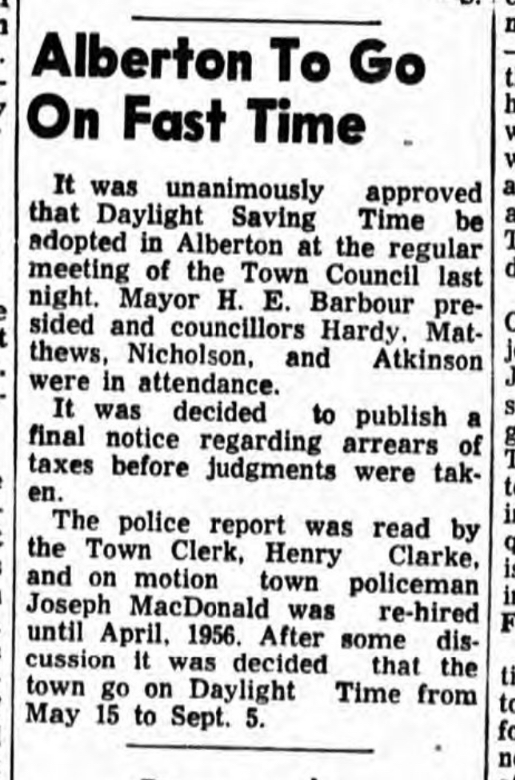

On May 10, 1955 it was Alberton’s turn:

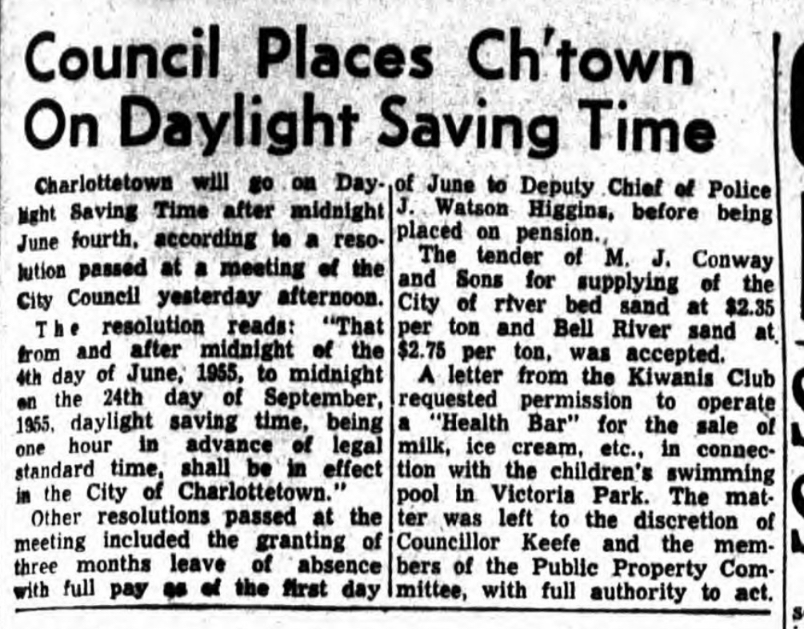

The big announcement from Charlottetown came on June 3, 1955, with a front page story in The Guardian (note that the founding of the Kiwanis Dairy Bar in Victoria Park was also considered at that same meeting; it’s there still):

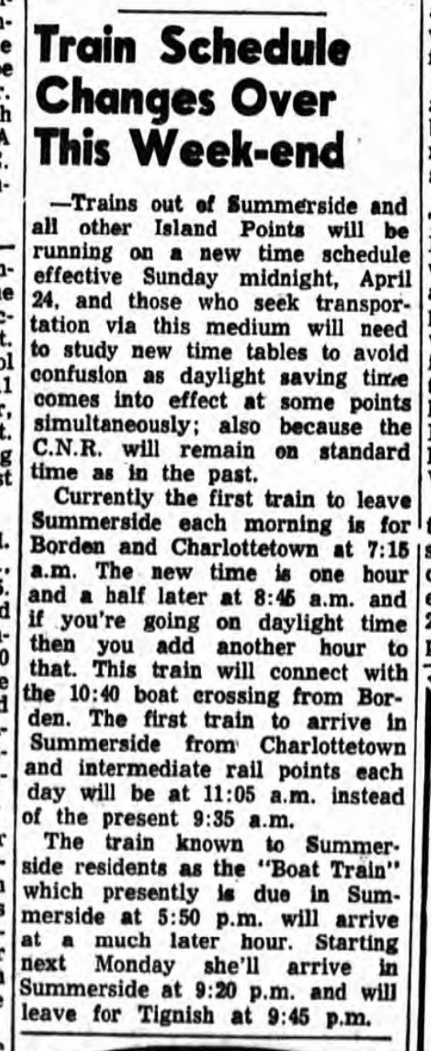

As you might imagine, having a province that was simultaneously running its rural parts on one time and its urban parts on another resulted in more confusion than that brought on by the Women’s Institute operating its Old Home Week booths on standard time while the rest of the fair operated on fast time. Take the trains for example, now long-gone, but at that time still running. They opted to keep their schedules on Standard Time when they announced a schedule update on April 22, 1955 in the midst of the swirling divergence:

I became interested in all of this when I returned to some research I started in 2014 on the history of time in Prince Edward Island, in part to determine whether PEI requires its own time zone in the IANA Time Zone Database.

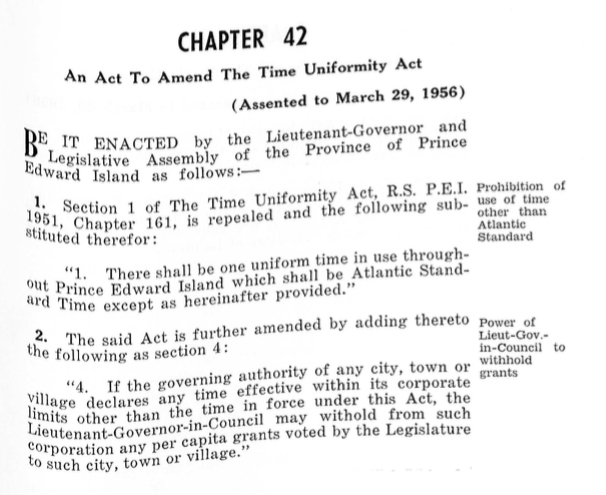

Simon Lloyd, Special Collections librarian at Robertson Library, helpfully assembled some relevant legislation for me in this regard, and among the materials he sent me was a copy of the 1956 Act to Amend The Time Uniformity Act. This piece of legislation says, in essence, “we’re using Atlantic Time on the Island, and if you’ve got a city, town or village that refuses to, we’re not giving you your grants anymore.”

This was the legislature’s reaction, one assumes, to the call from the PEI Federation of Agriculture for “necessary disciplinary sections which may be applied to municipalities whose Councils hold themselves to be, or act in complete disregard of the Legislature” in its report earlier in the month.

The passage of this amending legislation was not itself without controversy; indeed an opposite resolution, to allow urban areas permission to use daylight time, was “quashed” only 10 days earlier, as The Guardian reported on March 16, 1956 on the front page:

The paper’s report details the debate, and finishes with this:

Hon. Mr. MacDonald: “Are you for or against it?”

Mr. Bell: — No answer.

Mr. MacDonald: “Are you willing to see the city people set their clocks an hour ahead?”

Mr. Bell: “They got along all right last year.”

Mr. MacIsaac, the seconder of the resolution said the matter should not be a case of Country vs. City. “I am not convinced with the arguments of the rural members. It just doesn’t add up”, he added, “When we had daylight time during the war, the hay was made and the cows gave just as much milk, I cannot see why they can’t still do it.”

After the Leader of the Opposition had discussed the resolution briefly in Committee Mr. G.E. Saville moved that the Speaker take the chair, thus quashing the motion.

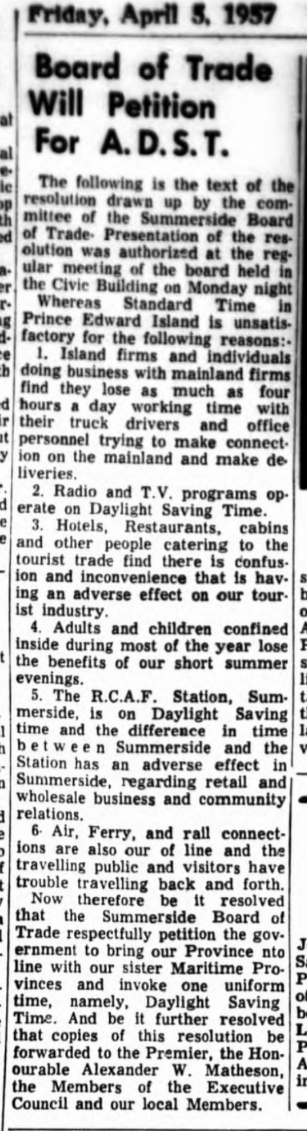

It appears that the government’s gambit worked, as the following year, in 1957, there’s no mentioned of “fast time” nor “daylight saving time” in The Guardian, save for the lobbying for daylight saving time continuing; The Guardian of April 5, 1957 reported a petition from the Summerside Board of Trade regarding adoption of daylight time, citing issues ranging from TV and radio schedules to the fact that the City of Summerside used standard time but the RCAF station had switched to daylight saving time:

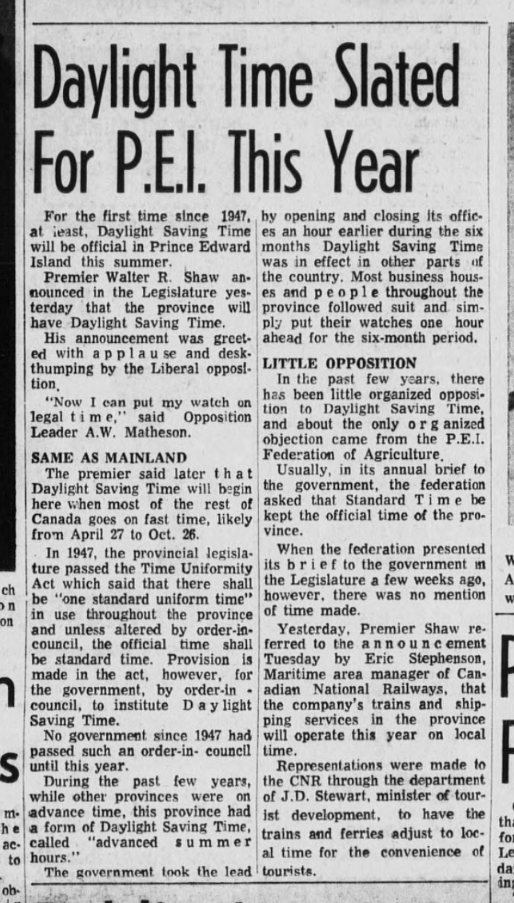

It was only six years later that the provincial wind changed direction. The Guardian on April 11, 1963 reported “Daylight Time Slated for PEI This Year” and mentioned that, unlike previous years, the PEI Federation of Agriculture had not included a call to continue Standard Time in its annual brief that year:

Prince Edward Island has been practicing Daylight Saving Time ever since.

Beyond the insights into the rural-urban divide in Prince Edward Island, this compelling saga does, indeed, bolster the case for an America/Charlottetown entry in the IANA Time Zone Database, as the adoption of Daylight Saving Time here, provincially, happened on a different schedule than either America/Halifax, America/Moncton, or America/Glace_Bay, which are the only other time zone entries in the region.

I’ll continue to prepare the documentation to this effect.

My friend Ton and I are engaged in parallel but otherwise uncoordinated efforts to, as Ton describes it for himself, “reconfiguring my online routines to increase privacy safeguards, and bring more of my data under my own control.”

For me this meant migrating my email to FastMail (still a third-party service, but more secure than self-hosting and under more of my control than Gmail), and migrating my calendar, contacts and file syncing to ownCloud (and, now, its fork nextCloud).

Ton also migrated to ownCloud for his file syncing, and has just completed an impressive migration from Gmail.

For both us, however, the final frontier is Evernote, which we both use extensively.

For me it’s ironic that I’ve left Evernote until last, as it’s where you’ll find my most private and guarded digital documents. My bills. A scan of my passport. Medical information.

In other words, it’s where I store almost everything that we’d generally consider “private information.”

Evernote, of course, offers some measure of security in its product, so it’s not like I’m storing files in the clear, but it remains mostly opaque, and certainly doesn’t meet Ton’s “under my control” test.

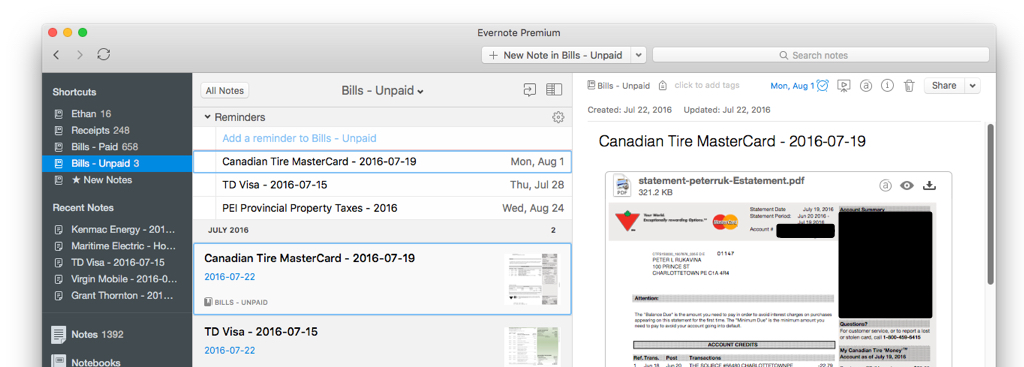

While I use Evernote to archive and make-searchable a variety of documents, the mission-critical use I make of it is as the backbone of my bill-paying workflow. Here’s how it works:

I get almost all of my bills these days via email (among the notable exceptions are, ironically, invoices from my accountant).

When a bill arrives by email (or when notification of a bill arrives by email and I visit a website, login, and retrieve it), I immediately file it in an Evernote note, attach a date due to it, and put in an a “Bills - Unpaid” notebook.

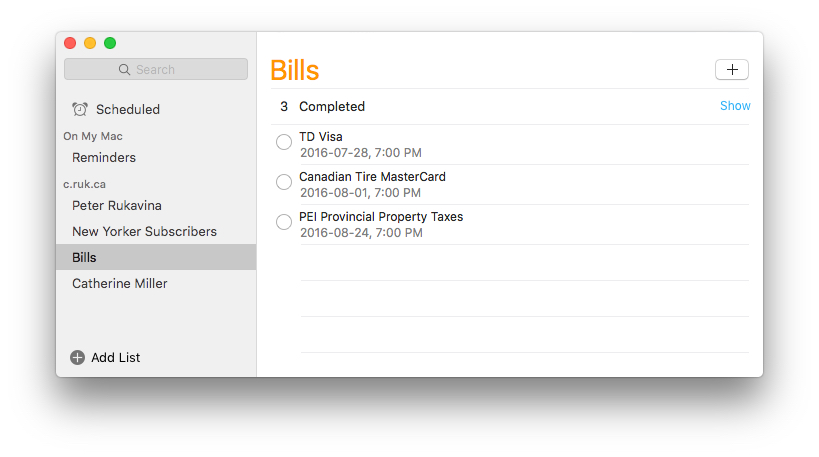

Here, for example, is the current “Bills - Unpaid” notebook showing a Canadian Tire MasterCard bill that’s due to be paid on August 1, along with a TD Visa bill due on July 28 and our PEI Provincial Property Tax bill, due on August 24:

When the due date arrives, Evernote emails me an alert and the Evernote mobile app on my Android phone sends me a notification, so I’m well-warned that it’s payment time.

When I receive this warning, I login to my Provincial Credit Union website, pay the bill online (except if it’s my accountant; I can only pay my accountant with a paper cheque).

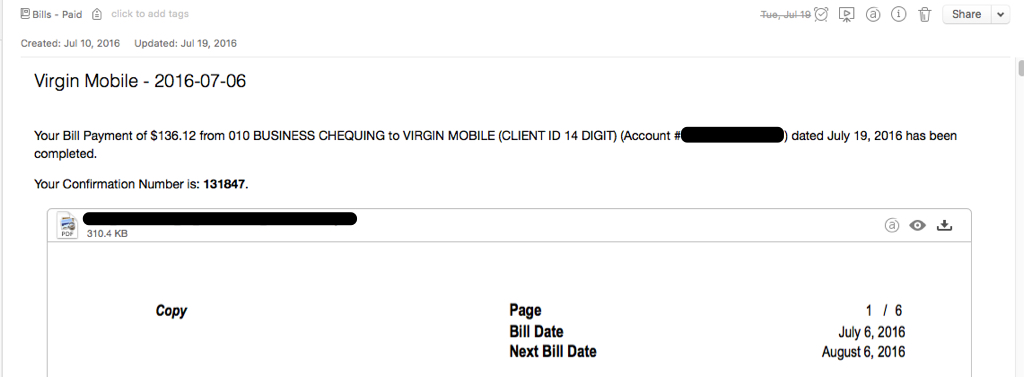

I copy and paste the confirmation message from the bill payment screen into Evernote, into the same note where I kept the original bill, mark the note as “done”, and move it into the “Bills - Paid” notebook.

Here’s our mobile phone bill for July from Virgin Mobile, for example, as it sits in this notebook now that it’s been paid:

Why do I use Evernote for this?

Breaking it down for myself yesterday, by way of figuring out what I need to replace it, here’s what I came up with:

- Evernote syncs notes between my devices: if I add something on my desktop, it’s available on my phone and on my iPad and on Evernote.com. This is, in general terms, functionality that nextCloud can replace, as it too is a syncing platform with desktop, Android and iPad apps.

- Evernote allows me to annotate my files. If I add a file, like a bill, to an Evernote note, I can also add payment information. While Mac OS X offers some file annotation capabilities, they are kludgy to use and not operating system independent, so it’s not obvious to me what the longterm replacement for this functionality is, save for some more cumbersome process like saving text files with annotations in the same filesystem folder as bills.

- Evernote allows me to attach alarms to notes. Like when a bill is due. I can likely replace this by adding alarms to my calendar or reminders apps.

- Evernote allows me to search my notes, and its OCR capabilities allow me to search inside of files inside notes. This is of limited use to me except at corporate year-end time when it becomes invaluable. Because of limitations with my Visa card and credit union online systems, I generally end up having to manually annotate 6 months of transactions every year (my bookkeeping is a yearly event, for the most part). Having the ability to quickly search for, say, “113.94” and find that it’s the amount I paid Bell Aliant for office Internet service in June, saves me hours of time. Mac OS X also offers some file search functionality, via Spotlight, albeit without the OCR capabilities, and this may or may not be enough to replace this. Perhaps I could use Tesseract to build a replacement?

It’s those four basic functions – sync, annotation, alerts, and search – that are Evernote’s magic sauce.

As a tentative step toward emancipation from Evernote, I’m experimenting, this month, with a new filesystem-based bill-paying workflow in parallel.

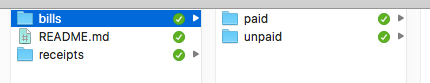

I’ve set up a simple folder, financial, in my nextCloud folder:

And I use the paid and unpaid folders in the same way I use Evernote notebooks. So when a new bill arrives, I put it in the unpaid folder.

I create an alarm in the Reminders application on my Mac (which syncs with my nextCloud via CalDAV, so it’s also available on my phone, via that Open Tasks app for Android):

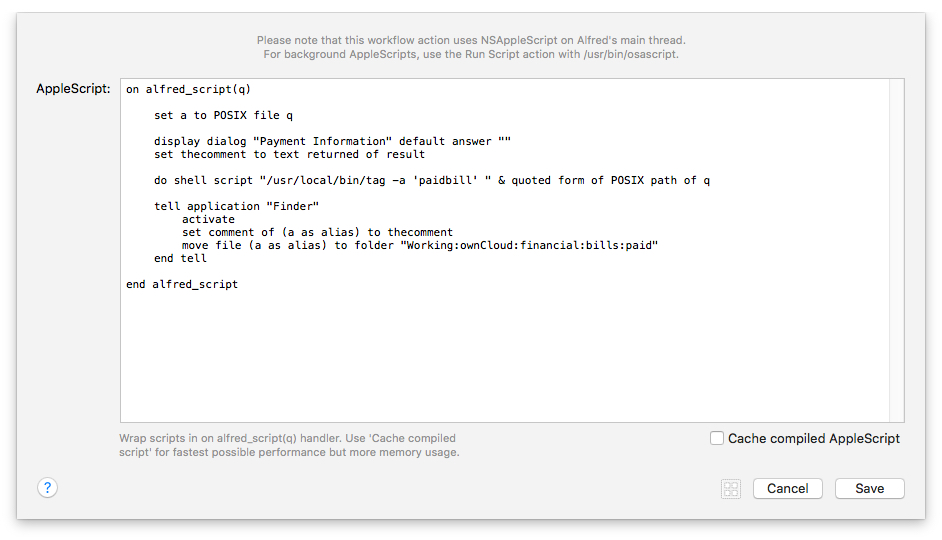

When I’ve paid a bill, I use an Alfred workflow I setup that allows me to select a bill anywhere on my Mac, double-tap the command key, and run this AppleScript:

This workflow prompts me to enter payment information – like the credit union payment confirmation number or the cheque number – and then tags the file with the OS X tag paidbill, adds the payment information as a filesystem comment, and moves the file into the paid folder.

I then mark the reminder I set as completed.

Using Alfred for this actually improves the usability of the workflow over Evernote’s a little. Using the already-syncing reminders apps on my phone and desktop solves the alerts issue. Using the tags and comments functionality of OS X tentatively solves the annotation issues, and using a nextCloud folder solves the syncing challenge (although the comments and tags, while they survive the syncing, aren’t accessible from other non-OS X devices). I’m still working on search.

I’ll do this for a bit, in parallel with my Evernote system in case I want to revert, and see how it goes.

A few minor updates here.

First, due both to a longstanding request from my friend [[Oliver Baker]], and to meet my own needs when using the 17 years of blog posts as personal reference (i.e. “what was I writing about on the day before the day I got my gallbladder out?”), I’ve added “Previous” and “Next” buttons to the bottom of every post (borrowing heavily, design wise, from Jeremy Keith’s version of the same feature):

Second, I’ve fixed some longstanding issues with the full text search (you knew you could search the site, right?). The search index was stuck for a while due to some unrelated hacking about. And the search now indexes my sounds and my travels as well as regular old posts. If you’ve never used the search feature before (and in typing this I realize that this all might only be of interest to me), it’s useful to know:

- You can search for phrases — just like Google et al — by surrounding your search keywords with quotes. A search for “open data”, in other words, will only find posts with that phrase, whereas a search for open data, no quotes, will find any post with either of those words or both.

- If you enter multiple words or phrases, the search will return posts with one or the other. If you want to find only posts with all of your words or phrases, put and between them. So a search for Charlottetown and fire will only find posts with both the words Charlottetown and fire in them.

- You can search for posts that don’t contain words or phrases by prefixing them with a minus sign. So a search for “tim banks” -ducks will search for all posts mentioning Tim Banks, except those that also mention ducks.

Finally, the archive of all posts I’ve ever written now goes back to the year I was born. Not because I was writing in utero, but because I’ve dated sounds my father recorded then by the date they were recorded. It seemed like the right thing to do.

Thank you for your continued patronage.

Many, many years ago I happened to be present on the day that Stefan Kirkpatrick was born. His parents were good and trusted friends, and I was happy to be a part of both that day and the early part of his life that followed.

When Stefan was two-going-on-three years old, I was, for a heady couple of months, his nanny. In El Paso, Texas. Which is a longer story for another day.

One of the elements of our daily life during that period, Stefan and I, trapped in suburbia on the cusp of America, was a cassette tape of The Three Little Pigs.

Stefan loved that tape, and wanted to listen to it over and over and over and over. And over.

I am, I think, a patient man at heart, but the 339th listening of The Three Little Pigs almost pushed me over the edge.

But I survived.

That I was able to emerge with my faculties intact from that nannying experience was, in no small way, what gave me the confidence to think that I had it in me to be a father; I owe him a great debt for that.

Young Stefan is now slightly less young: he is in his twenties and lives on the shore in Nova Scotia. He is a parent himself. And, with his partner Desiree Gordon, a farmer of water buffaloes. Which is what you hear Stefan and Desiree talking to CBC Information Morning’s Phlis McGregor about in this radio piece.

My favourite part of the interview is when Stefan talks about the nature of the water buffalo as a large, dangerous, friendly beast:

They’re so gentle. It’s like any kind of large tool that can kill you: you still have to be cautious of the fact that they’re massive creatures. But they’re really easy to get along with. Really friendly.

My small slice of a contribution to Stefan’s upbringing was likely insignificant in shaping what he’s grown into as a human being, but could it be that whatever patience allowed me to play The Three Little Pigs for the 340th and 341st times engendered both the patience for and interest in small scale agriculture? Let’s say yes, just for fun.

Given that I was born on one side of Lake Ontario and grew up on the other side, you might say I have the Great Lakes in my blood.

And even more so because my father, a nearshore sedimentologist, was engaged in a survey of the Great Lakes over much of my childhood, and so my strongest childhood memories are camping on the shores of one of the lakes or another, usually in a provincial park, while my father was “in the field.”

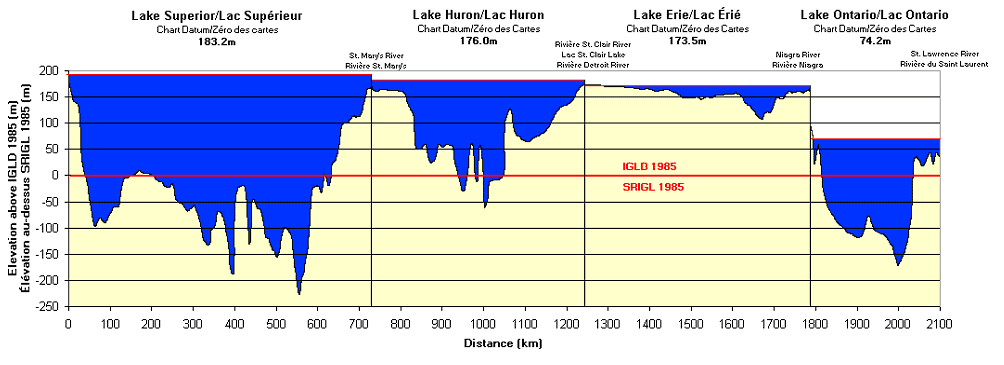

This might explain why I find this visualization of the International Great Lakes Datum so compelling:

The visualization shows the Great Lakes from Lake Superior (where my father, and before him his mother, were born in Fort William) through Lake Huron and Lake Erie and Lake Ontario to the St. Lawrence River (from which I get my middle name).

The depths shown are from the the 1985 International Great Lakes Datum, which is a set of depths that, as explained here, establish a reference point from which to measure:

For navigational safety, depths on a chart are shown from a low-water surface or a low-water datum called chart datum. Chart datum is selected so that the water level will seldom fall below it and only rarely will there be less depth available than what is portrayed on the chart.

In other words, if you’re going to measure the depth of something, you need a commonly-held understanding of where “zero” us. That’s this.

Beyond visualizing a technical system for measurement, the graphic also illustrates wonderfully how deep Lake Superior is, how shallow Lake Erie is, and why there is Niagara Falls (between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario).

If you want a primer on the Great Lakes, there is no better one than The Rise and Fall of the Great Lakes, the 1968 Bill Mason film.

I am

I am