Two photos I took last night of Fleet, by artist Alexis Bulman, mounted in the waters of Charlottetown Harbour off Beaconsfield last night as part of Art in the Open. My camera, of its own volition, took two photos in rapid succession with different settings, and I animated them together (the lights in the floating tents don’t actually pulse like this, at least not in a way that the human eye can see). I enjoy the notion that the tents might have come alive without us noticing.

As summer fades out of focus, here are three new things to take you into autumn:

- Cucumber-Mint Soda from Upstreet Craft Brewing. Sometimes you want to go up the street and play Apples to Apples, but you don’t want a drink drink. Or perhaps you simply don’t drink beer at all. It seems odd that cucumber and mint would combine to be your salvation, but it works. If you’re not so brave, there’s also a sour cherry-based soda.

- Purity Milk at Lawtons in the Polyclinic. We of the Purity-preferring clan have long been challenged, especially on the weekend, with finding a handy source for milk from Purity Dairy. Catherine turned me on to the fact that Lawtons sells Purity products; it’s at 8:00 a.m. weekdays, 9:00 a.m. Saturday and 11:00 a.m. Sunday. Maybe not a new thing, technically, but news for me.

- The Humble Barber, above COWS at the corner of Queen and Grafton, and, specifically, Zack Squires, cut my hair last Saturday. I’m a longtime Ray’s customer, so this was a departure for me, but [[Oliver]] spoke so highly of Zack’s talents that I had no choice by to try. I was not disappointed: Zack is an accomplished barber and a genuinely curious conversationalist. I will be back.

You may recall that a year ago, Nadja, the eldest daughter of my dear old friends Yvonne and Bob, landed on Prince Edward Island with friends, a leg on their post-graduation east coast tour.

Fast-forward a year, and Nadja is now thousands of miles away, rough camping in a Slovakian castle with her partner Hannes.

Next week they’re headed for Berlin and, challenged for a place to stay, asked me if I knew of someone they could crash with.

My friend Morgan gamely and generously volunteered.

Which is how I found myself today chatting with Morgan in Berlin via Twitter in one window and Nadja in Slovakia in another, coordinating details of said arrangement.

I haven’t been this connection-proud since I arranged for Nadja’s cousin Cal to visit SoundCloud 4 years ago.

You are a generous city, Berlin.

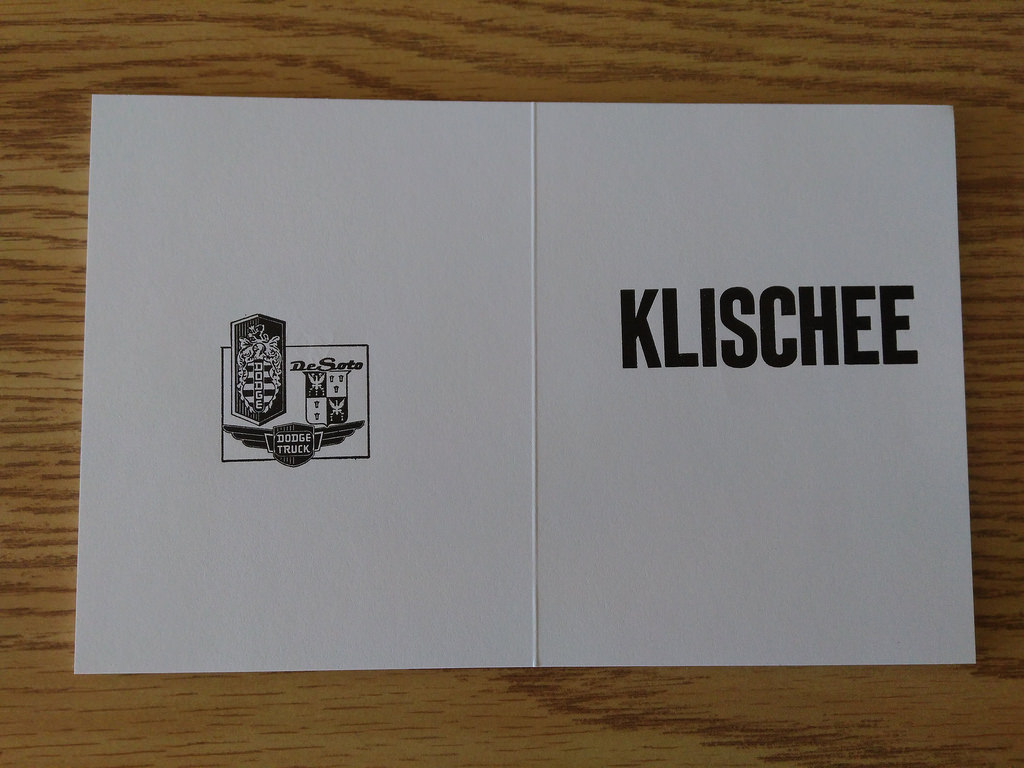

Here’s a photographic journey through the process I took to set, print and bind a book of klischees. Making books, it turns out, is well within the realm of the possible for everyday people: all you need is paper, glue and patience.

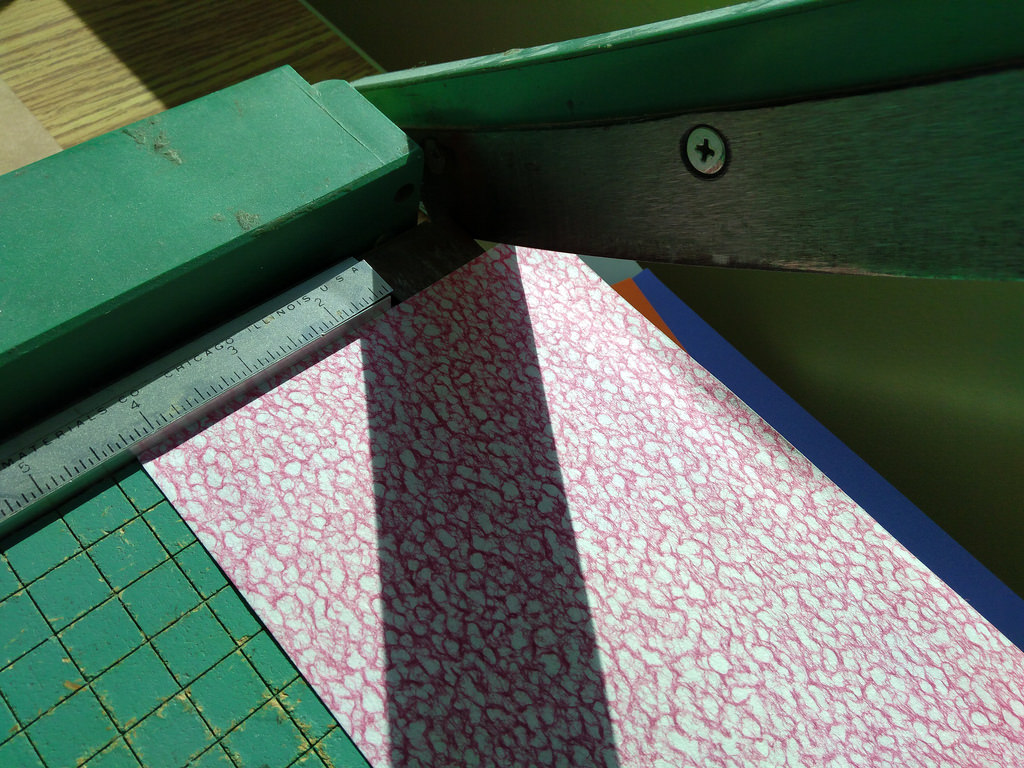

Printing

I started by printing the signatures for the book. On standard letter-sized card stock I printed four klischees on each side. The setup in the chase looked like this:

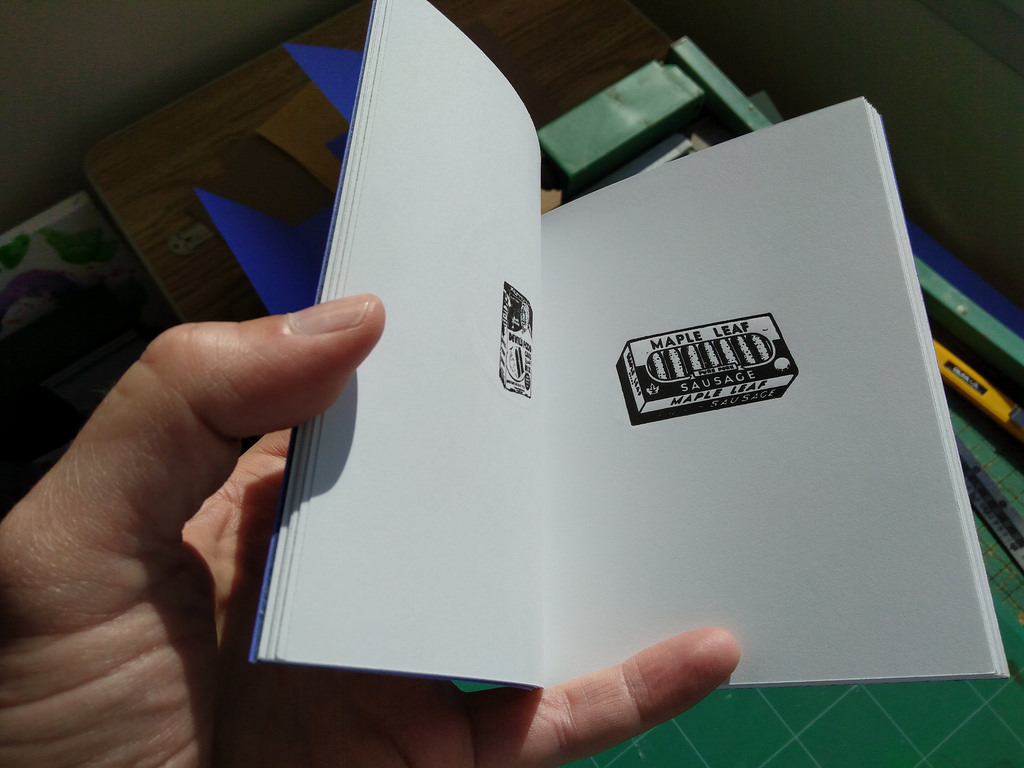

And a prototype of the finished signatures looked like this:

The printing took several weeks, off an on when I had time. I printed in batches of 2 or 3 pages a session, and ended up with seven pieces of 8-1/2 x 11 inch card stock printed double-sided. When I sliced these in half I had fourteen pieces of 4-1/4 x 11 inch card stock, ready for folding.

Scoring and Folding

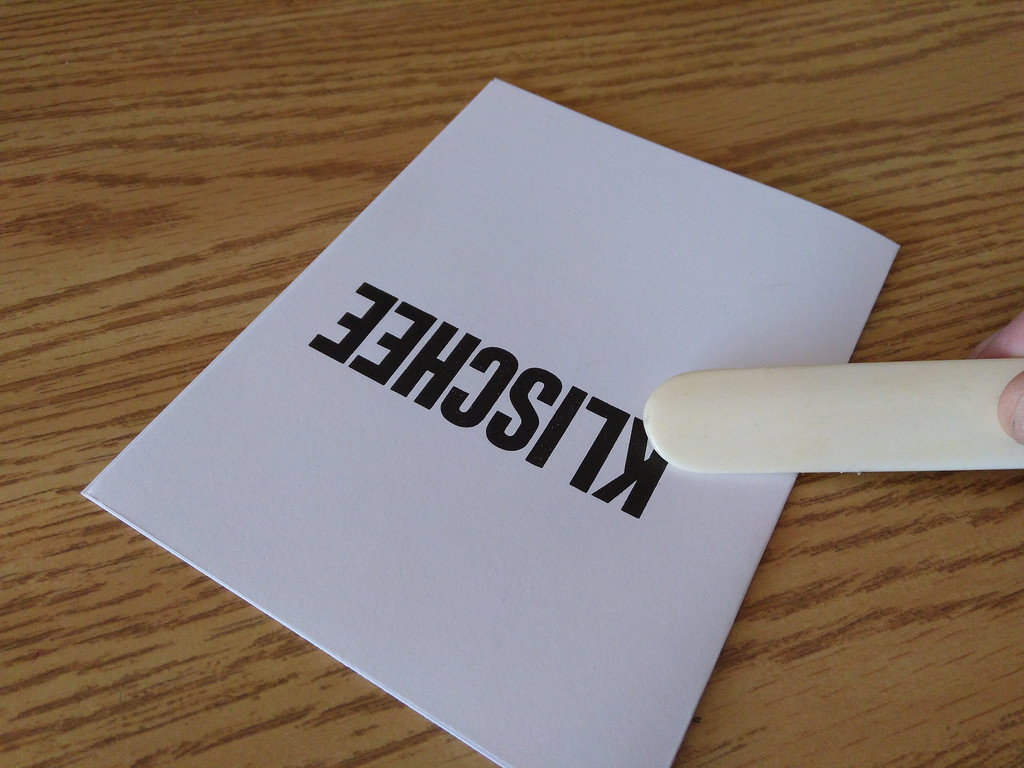

I scored each of the 4-1/4 x 11 inch pieces:

Then folded each on in half along the score:

I then used a bone folder – an invaluable tool that only appears to have any utility once you actually use it for something – to enhanced the folding a little:

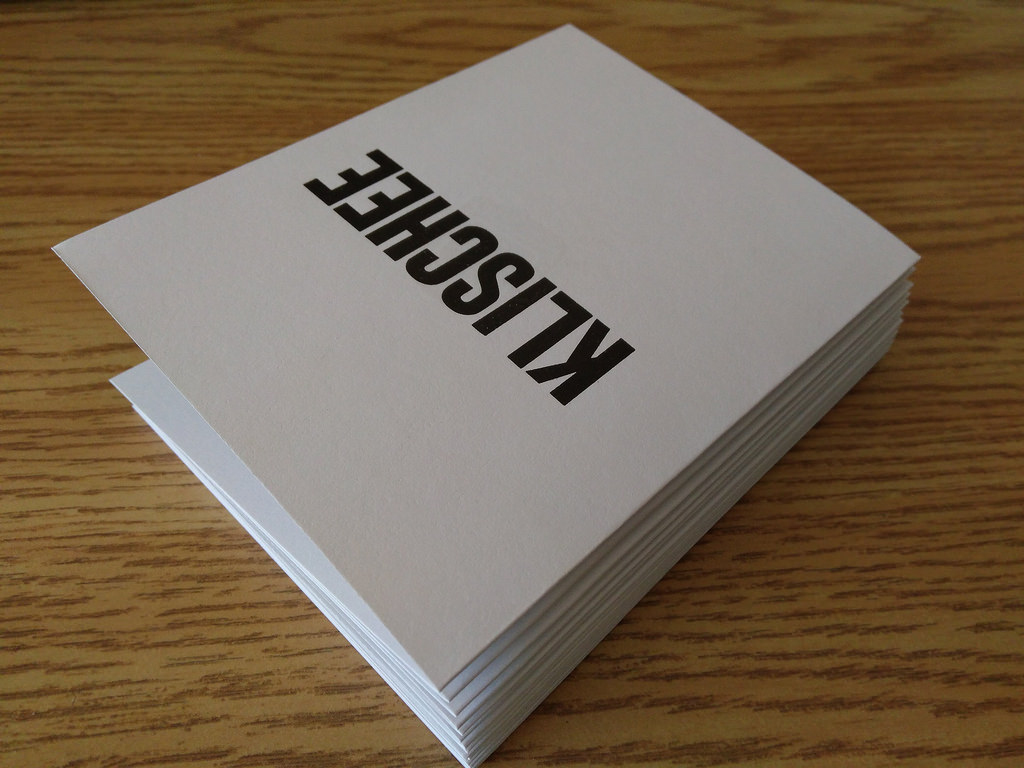

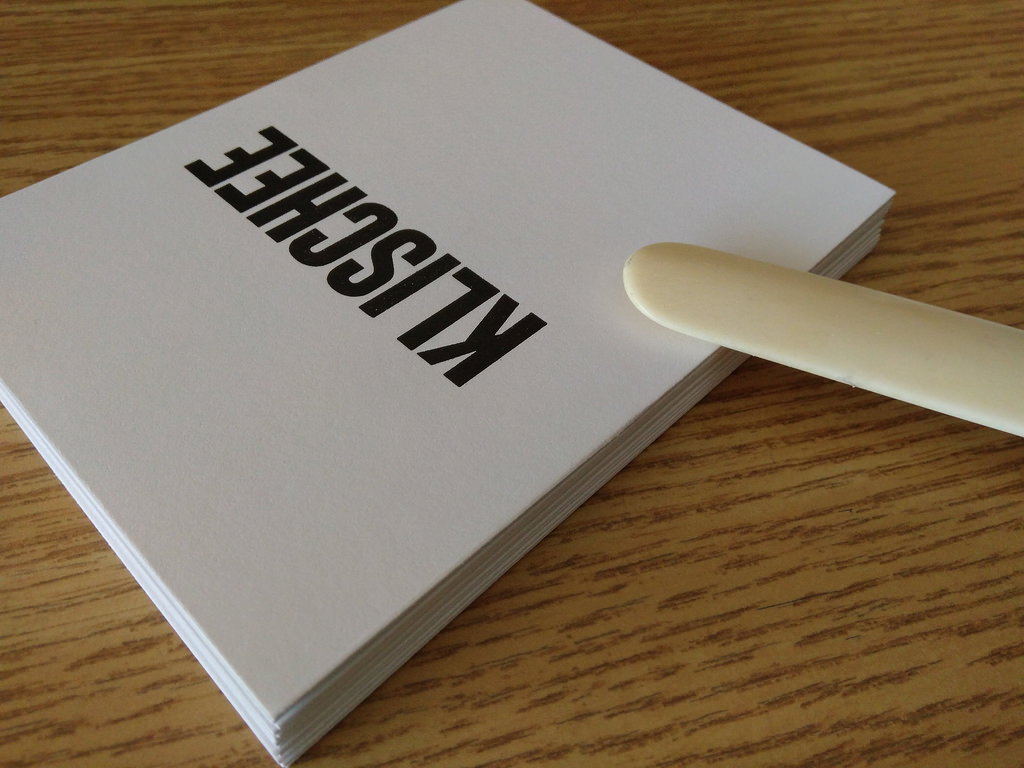

I ended up with a stack of folded signatures:

Which I then compacted with the bone folder (this turns out to be a key step: it’s what takes “ragtag collection of folded pieces of paper” and turns them into something book-like):

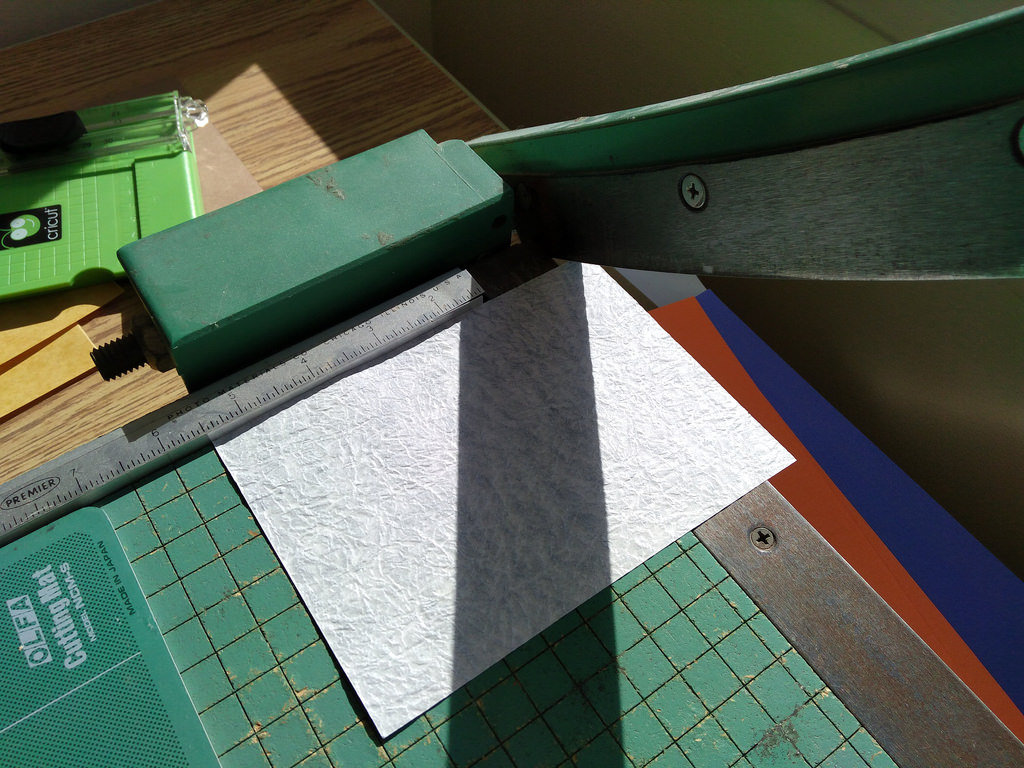

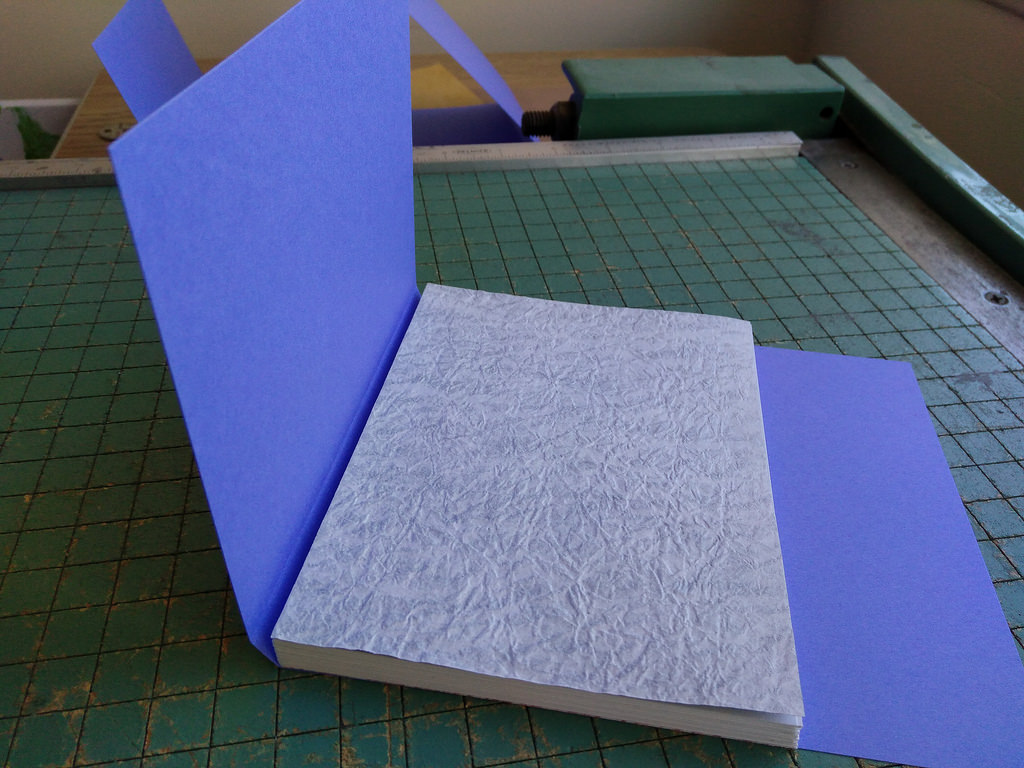

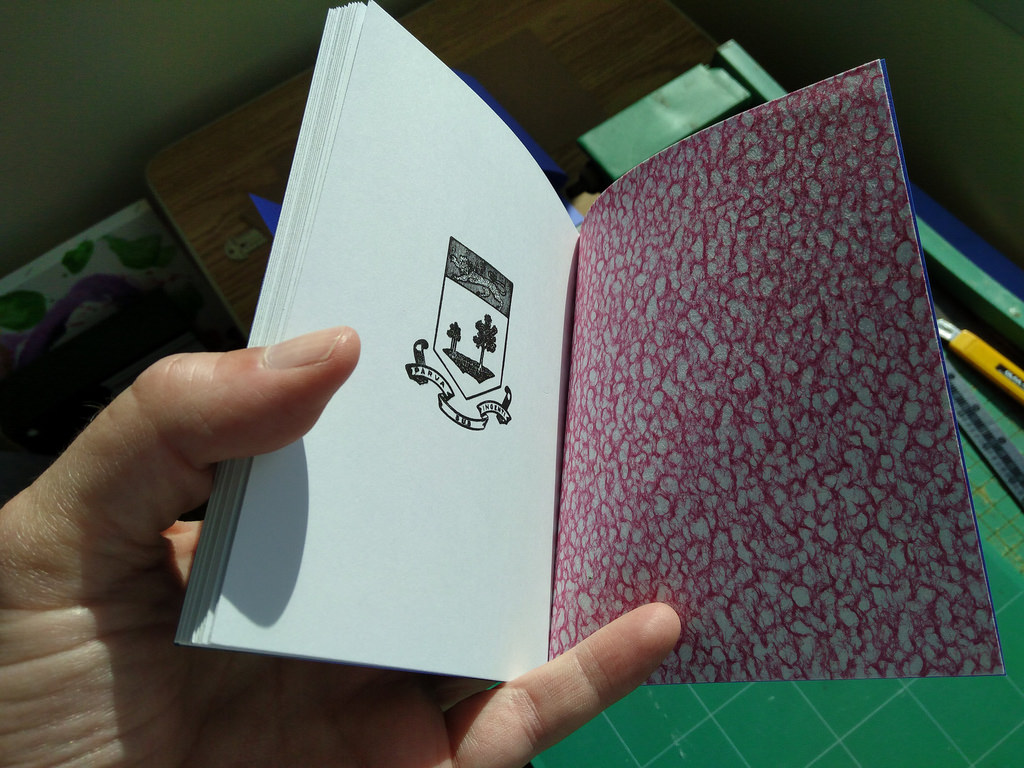

Next, I pulled two pieces of Japanese paper out of my paper closet and cut them to size (4-1/4 by 5-1/2 inches) to go at the start and end of the book:

The finished product, before gluing, looked like this:

Gluing

With the book ready for glue, I clamped everything together with a binder clip; this is so helpful in keeping everything in alignment, and this kind of binder clip is much easier to manage than the more common “black with silver parts that fold back” kind, especially when it comes to removing it:

I slipped the clamped signatures into a book press (a piece of equipment helpfully left in my office by the previous occupants), and then clamp the whole thing tight in the press, while gingerly removing the binder clip:

I then used a cheap paintbrush to spread a thin layer of regular old white glue (I used Aleene’s Original Tacky Glue, but I imagine any brand would do) along the edge of the book:

The brush is very useful for creating a really smooth layer of glue. I repeated this process again once the first layer of glue dried (this may not be technically required, but it afforded me some gluing-piece-of-mind):

Preparing the Cover

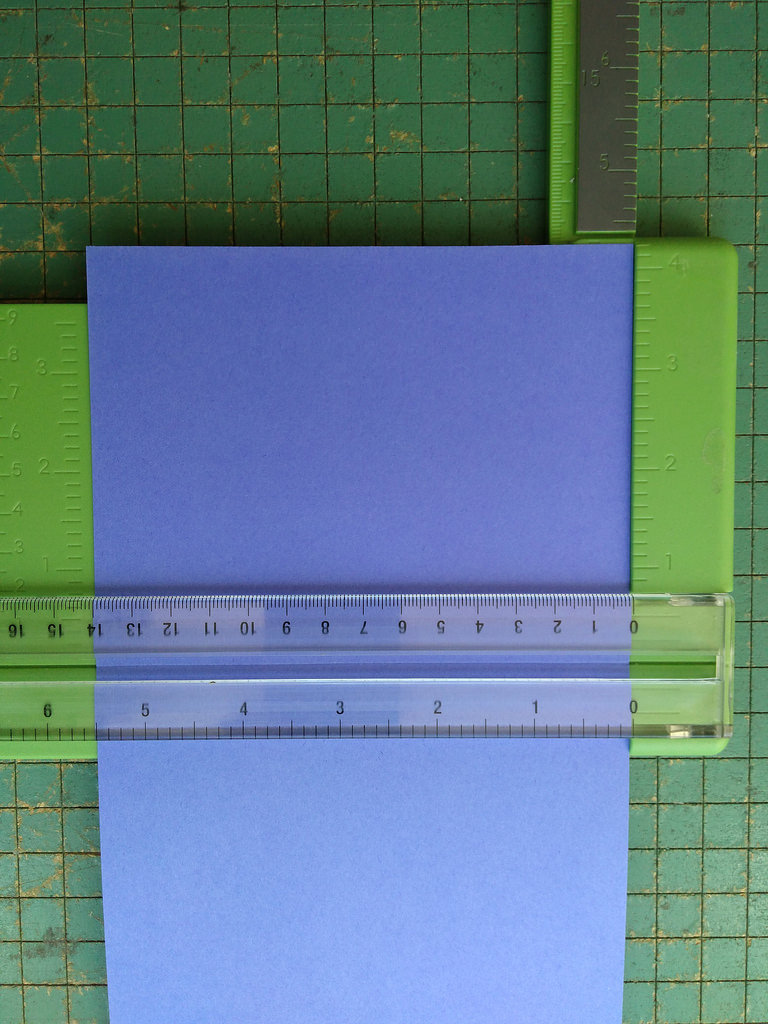

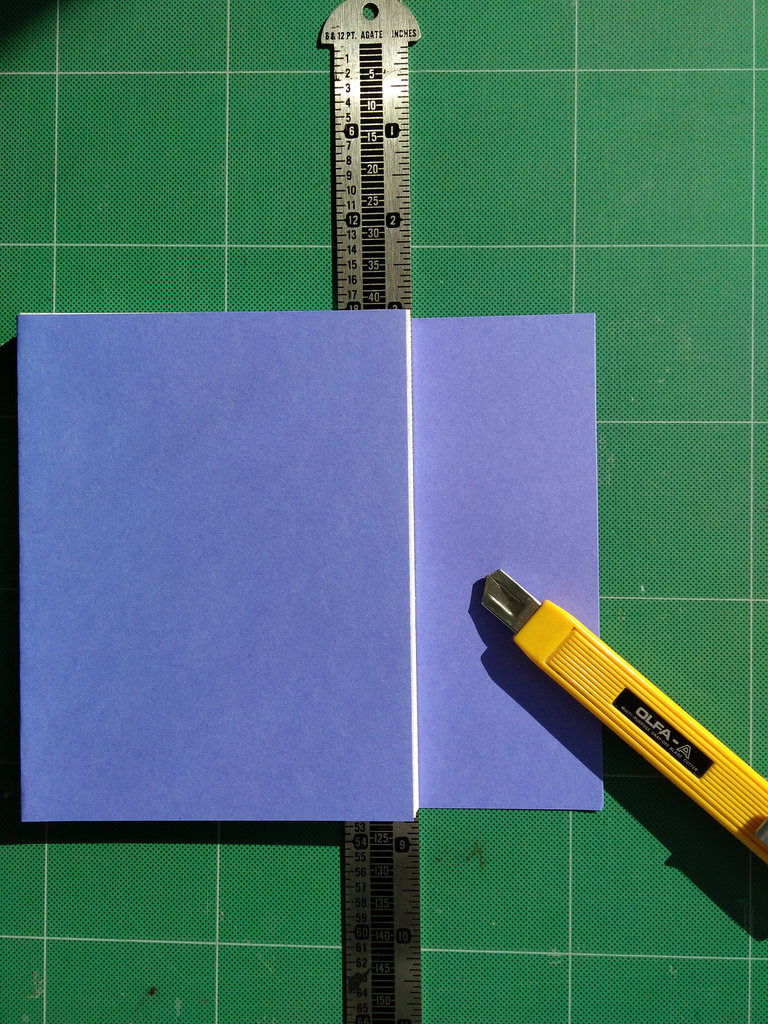

While waiting for the glue to dry, I took a piece of letter-sized purple card stock and trimmed it down to 5-1/2 by 11 inches, and then scored it 4-1/4 inches in:

I then added a second score, using the glued book block as a guide to the location. The result was a front cover, spine, and back cover; I left the back cover to trim after the cover-gluing:

Gluing the Cover

I spread a layer of glue along the spine of the book block, put the cover in place, and then clamped the result into the book press (not so much for the pressure as to have it clamped in place so I could apply some pressure to the spine of the book with my thumb to remove glue bubbles):

Trimming the Cover

Once the spine had dried, I removed it from the book press and, using a straight edge as a guide (an excellent tip I picked up from a YouTube bookbinding video), I trimmed the back cover:

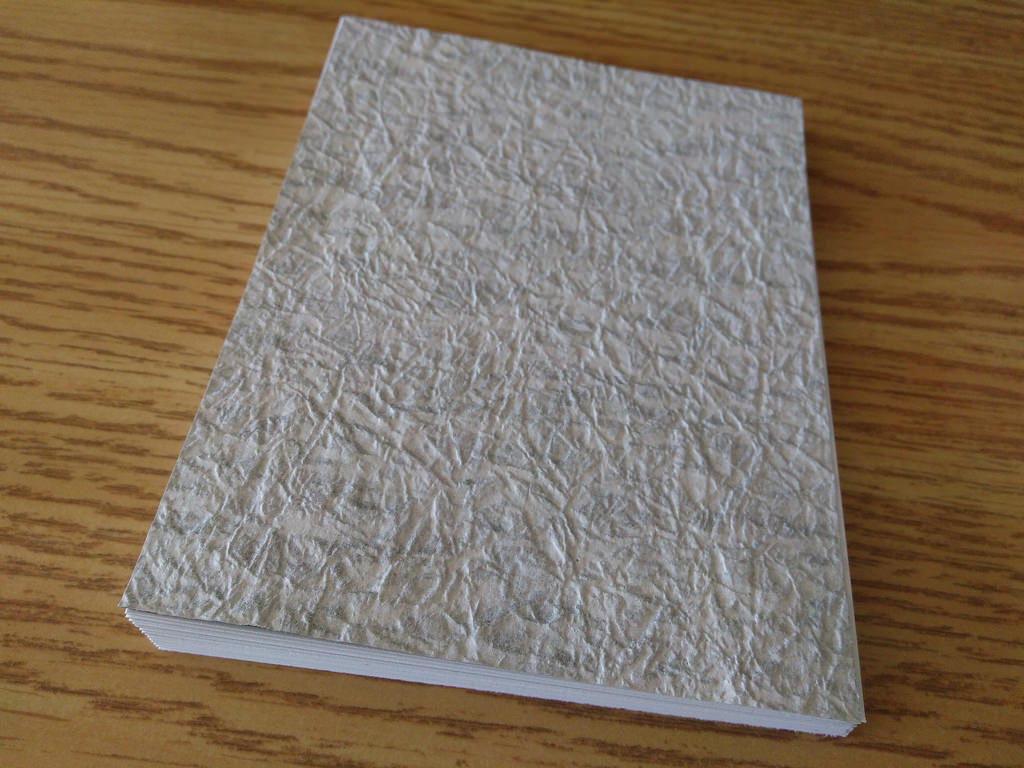

The Finished Book

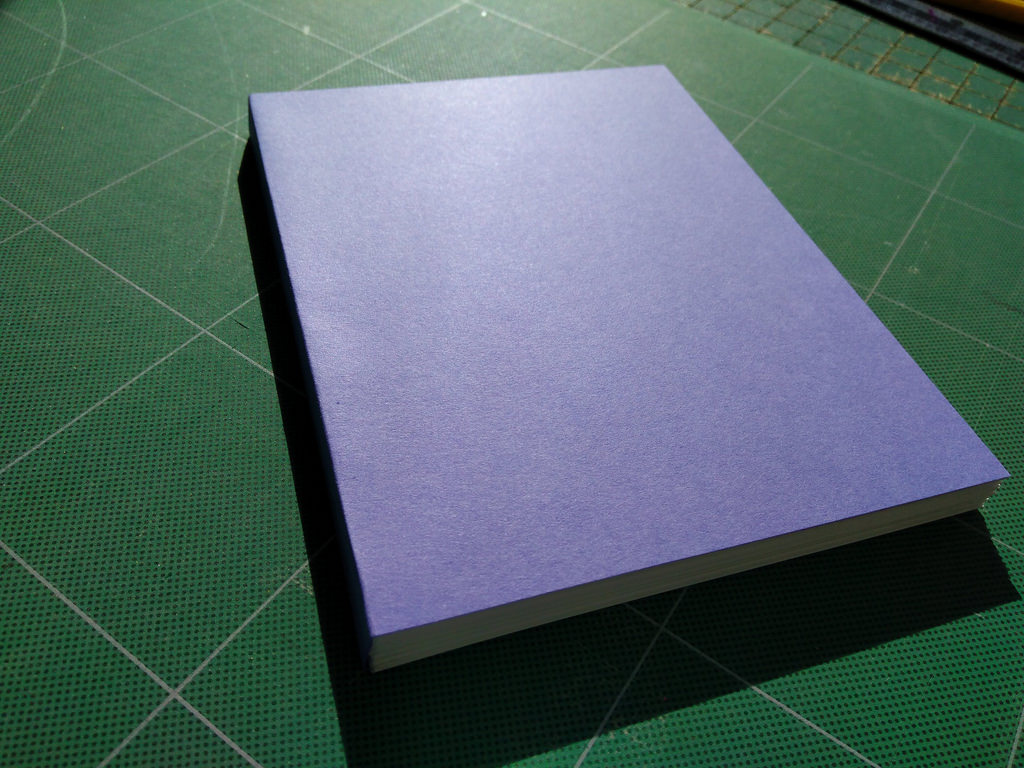

The finished book looks remarkably book-like:

From The Guardian, 100 years ago today in 1916, reporting on the “Rogers Case,” wherein W.K. Rogers was charged with “illegally operating an automobile on July 9th.”

As soon as Comma Queen coming to Victoria Literary Festival appeared in my river of news, I knew this was a place I had to be.

The “Comma Queen” is Mary Norris, a query proofreader at The New Yorker. You may know her from hits like Whichcraft: That vs. Which, and Pronouns for Pets—“That” and “Who”.

If, like me, you pray at the church of The New Yorker, when someone from 1 World Trade Center comes to your remote outpost, you go.

The Victoria Literary Festival, it turns out, is a low-key late-summer event that the intelligentsia of the tiny seaside village stage mostly for themselves. Although, as organizer Linda Gilbert said in a CBC Mainstreet interview, “we’ll let other people come… it’s for anyone who happens to be around.” A Victoria kind of thing to say.

Mary Norris was part of a triple bill that started with tea expert Linda Gaylard, ruminating on tea and grammar, and continued with a performance piece by choreographer Julia Sauvé. Each act was punctuated by an intermission, with cocktail, sandwiches and chocolate.

All of this shoehorned into Island Chocolates’ space on Main Street.

It was, in other words, about the best possible event you can imagine, in about the best possible location you can imagine.

The crowd was an enthusiastic bunch of high society types and earthy locals; a pleasant bunch to be among.

Norris held court, complete with the comma crown and the comma shaker. She’s a compelling speaker, a skilled explainer, and was willing to entertain my fanboyish questions about the magazine.

How did tiny Victoria manage to attract someone of such import, someone whose upcoming gigs include the Italian Consulate in Dublin and Shakespeare & Co. in Paris? According to Linda Gilbert, and confirmed by Norris herself, they simply asked. And she said yes.

As the night drew to a close, I bought, and had signed, a copy of Norris’s book Between You & Me, grabbed a chocolate R for the road, and headed out into the dark streets of Victoria to find my car.

Walking from picking up the mail up the street, past Zion church, across the street to Church Street and by St. Paul’s, where a lone piper stood under a tree, sheltered from the rain. Across Queen’s Square in front of the Coles Building and along Richmond Street to work.

As my father, a nearshore sedimentologist, conducted field work on the Great Lakes over the 1970s, our family spent part of each summer in one provincial park or another.

Some of my strongest childhood summer memories are of park wardens, dressed just like those in Forest Rangers, and their interpretive programs. They showed The Rise and Fall of the Great Lakes at night in the park amphitheaters, and, during the day, they taught us kids about salamanders and lake pollution and clouds and species of trees.

They were also responsible for managing the parks, checking people in and out, and dealing with any issues that arose (loud campers, low toilet paper, broken teeter-totters).

While the provincial park wardens were in charge of “park security,” they never seemed like security guards to me, and they seemed to spend as much or more of their time helping as they did hindering. They were, as a rule, amiable, engaged people who left you with an impression that the core of their role was to help uncover a tiny bit of the natural world for all who passed through their gates.

I’ve been thinking a lot about provincial park wardens of late, especially in regard to what I might generally call “public access user interfaces.”

When Premier Wade MacLauchlan took office in 2015, one of his first actions was to address senior directors in the provincial public service. In his speech he described “ten lenses” through which he intended to make decisions as Premier; in the preamble to discussion of these lenses he touched on the larger general issue of “openness and engagement”:

I have spent the past three years studying and writing about the time in office of our longest-serving premier, Alex B. Campbell, who was well-known for seeing people in his office and for reaching out to the public, including by picking up hitchhikers. For reasons that most of us consider regrettable, including basic personal and public safety, some of the openness of an earlier day has had to go by the wayside as we introduce more security-minded cautions and procedures. As you know, my first week in office included threats on my life that have led to criminal charges. This is not a business for the feint of heart.

While adding security precautions imposes regrettable restrictions on the habitual openness of our premiers, these are measures that can be considered and implemented according to our best judgment and our ability to learn from practices in other jurisdictions. The more nuanced questions of judgment or personal style come when we consider how to strike a balance between openness or accessibility and the availability of time, which is the scarcest resource when it comes to governing. These questions get at the core of how the premier and the entire public administration strike a necessary balance between delegation and coherence.

The “security precautions” he spoke about are ones that have sprung up over the last 16 years since 9/11, and have involved a dramatic limiting of public access to the Shaw, Sullivan and Jones buildings that form the heart of the public service office complex in Charlottetown. Every government employee was issued an electronic ID card, access gates and elevator limitations were added and security guards installed in each building to control access and register visitors.

The end effect of this means, for example, that to visit the Government Services Library in the Jones Building one must now register with a security guard, provide photo identification, and wear a visitor name tag during the visit.

The “habitual openness” the Premier spoke about (which was a feature both of premiers and of the public service in general) was how things were before all this: almost completely unfettered public access to the entire government complex. I used to joke that it was possible for any citizen to walk into the Shaw Building, get in the elevator and go up to the 5th floor, walk into the office of the Minister of Labour and sit in their desk, feet up, without anyone asking the time of day. And that wasn’t much of an exaggeration.

While the force of security officers that person these new posts are generally not unfriendly, the prevailing sense visitors are left with, from the way the officers present themselves, and the way they are positioned physically, is you don’t belong here.

These security officers are, in other words, the opposite of my childhood park wardens: their help-to-hinder ratio is flipped and they in no way serve the role I think they should be playing, that of a friendly, helpful front door to government.

While the Premier, and the post-9/11 security establishment in general, are never going to win me over to the “more security-minded cautions and procedures” movement – I feel that, more often than not, action on the perceived need for more security begets little but a greater perceived need for more security – I think one thing we can take action on without trying to decide the larger “regrettable-but-necessary-security” issue, is what we might call the “interface design” of government complex access.

It is in our collective best interests that government operates – and is perceived to operate – as by, for, and of the people. The quality of the relationship between citizens and our public servants is key to this goal, and the more roadblocks, real and perceptual, that we put between them, the more we place the quality of this relationship in jeopardy.

There are some people who are really, really good hosts of dinner parties. They greet you at the door with open arms. They take your coat. They make introductions. They offer you a glass of wine. They recognize the inherent tensions of the setting, and do everything they can to mitigate them. Like provincial park wardens, they optimize for help not hinder.

This is what we need standing between us and the public service: rather than security officers, we need government wardens.

Government Wardens would be part concierge, part data analyst, part party host, part telephone operator, part counselor. They could certainly control access, if access control is needed, but the people in the role, and the physical systems supporting them, would be about enabling access, not preventing access. The message they would convey to the citizen visiting their government is you do belong here and, further, that this place is your place; of you, for you, by you.

Fortunately this is not something we need invent from scratch: think of that really great dinner party host, or the front desk staff at the best hotel you’ve ever stayed at, and you’ll understand the role. There are people who are inherently good at this; we just need to cast them. And we know a lot about how to build approachable spaces that we didn’t know in the 1960s when the government complex was planned; we can reconfigure physical spaces to be more comfortable, more useful, more engaging. And, indeed, more secure.

Wouldn’t it be a wonderful thing to walk into the new Public Engagement Atrium, built, Reichstag Dome-like, around the existing government buildings, and be greeted by a helpful, smiling warden who would help answer questions, find the right public servant, or service, or application form for you. You could have a coffee. Browse the Internet. Use the library. Renew your driver’s license. Learn how to access open data feeds. Organize a meeting in one of the light-filled democracy incubator spaces freely available. You could even learn about salamanders.

I think we can realize this goal, and I think the long-term affects on how we view ourselves and our government will be profound. Lens number four in the Premier’s address to the public service was titled “an engagement lens” and he said, in part:

Governments everywhere must continuously seek better ways to serve people and engage them. Government must be open and transparent, and take full advantage of modern technologies and media platforms to facilitate access to information and knowledge of government programs and services.

Job one in this regard, I hold, is re-configuring government’s front door, replacing security guards with wardens and changing “move along now” with “how can we help you?”

I stand ready to help.

From Warren Ellis, Finding the System that Works for You; in part:

I’m aiming for an unbroken two-month stint on MORNING COMPUTER. I have a hand-drawn grid for it on the wall, above the whiteboard, that takes me up to October 2, and I intend to put crosses in every box on that grid. (The Seinfeld Chain.)

The key pull-quote from that is not “don’t break the chain.” but “skipping one day makes it easier to skip the next day.”

I know what works for me in terms of productivity. Like “don’t for fuck’s sake put Netflix on the big screen.” I will produce a lot less every day if I let a tv show run on Netflix. Sometimes it works as background noise, but often it draws my eye too much – video claims too much attention. What works better is throwing up a nature documentary or an art film, something slow, and mute the window, and then put music on.

This conversation-while-fishing between authors Thomas McGuane and Callan Wink covers some of the same ground. For example:

McGuane: I’m just thinking about writing.

Wink: Are you on the everyday program right now?

McGuane: Not really, uh, pretty good.

Wink: Yah, I feel like when I have a good stint of doing it a lot then it all just becomes easier, you know?

McGuane: That’s absolutely right.

Wink: Taking a month off, like I basically do, for guiding – even a couple of months – then it’s just a tortuous process to get back anything in shape for writing.

McGuane: That is the best reason for having regular work hours, is to not beat yourself up when you try to start up again.

And then the fish start to bite, and off they go. Their conversation on this and other topics is fascinating, in part because they are both masters of a craft (writing for McGuane, guiding for Wink) who can appreciate (and, indeed, practice) the craft of the other.

In my experience these are some of the best relationships to forge, and I’ve been lucky over my life to have been able to teleport my digital skills into conversations with smart, experienced people in all manner of other domains: because we each end up being a tiny bit in awe of the others’ seemingly magical abilities, we remain humble and that’s a good place to start a relationship.

I’ve now written more blog posts in the space year-to-date than I’ve written in an entire year since 2009. Mostly that’s because I decided that this was going to be the place I focused my pith, rather than scattering it among the social media fields.

I’ve never enjoyed writing more, and my experience mirrors Wink’s: when I have “a good stint of doing it” it does, indeed, “just become easier.”

I am

I am