If there was every a headline from The Guardian that could also be a secret password to gain admission to an underground club, this is it.

When I started working with the Province of PEI on its website in 1995, Wordstar 2000 was the word processor used by most public servants in the province.

Within a few years it was largely replaced by WordPerfect and, years after that, by Word. Which is what’s mostly used today.

One of the last Wordstar 2000 holdouts in government was the Legislative Counsel Office, which drafts and maintains the province’s acts and regulations. They’d carefully worked out a system for laying out legislation in its section-by-section, clause-by-clause format, complete with the marginal notes.

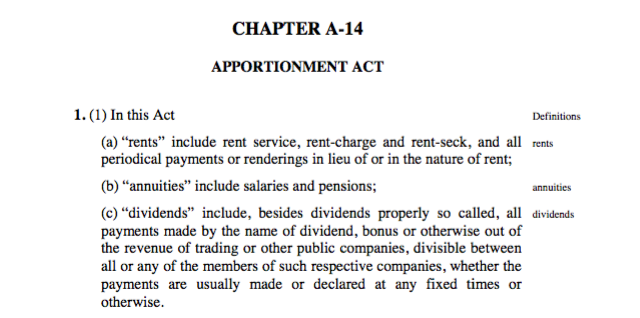

It was this marginal material that was the fiddly bit; the words like “rents” and “dividends” in this example, that need to line up with what they refer to:

Those marginal notes are an important part of legislation, and long after the rest of the public service had moved on to WordPerfect, the Legislative Counsel Office continued to use Wordstar 2000 because of the difficulty of migrating and preserving this element of the layout.

It’s because of this that PEI was relatively late to getting its acts and regulations online: Wordstar 2000 provided no way of producing PDF files, and so we had to wait until it was replaced before legislation could go online as a collection of PDFs.

I was reminded of all of this when I came across John C. Dvorak’s Whatever Happened to Wordstar? essay today, a well-worded review of the history of Wordstar and its descendants.

Here’s the part where Wordstar 2000 comes along:

While Wordstar was still the best word processor on the market until the mid-1980’s it lacked a couple of features that annoyed users. As DOS was improved and UNIX-like paths were added, Wordstar could not initially accomodate paths. Worse it had no UNDO key. The code base by now was turning into spaghetti code and Barnaby wasn’t around to fix things. Worse, in 1985, the company produced Wordstar2000, a copy protected program that was nothing like the older lovable Wordstar and which contained annoying copy-protection features that scared most users away. While many pundits including Esther Dyson predicted great things for Wordstar2000, users rejected it. The product was big and slow and expensive. And despite complaints by the company and others, people wanted software they could copy and use on more than one machine. During this era piracy sold software and created market share. People would use a bootleg copy of Wordstar and eventually buy a copy. Wordstar may have been the most pirated software in the world, which in many ways accounted for its success. (Software companies don’t like to admit to this as a possibility.) Books for Wordstar sold like hot cakes and the authors knew they were selling documentation for pirated copies of Wordstar. The company itself should have just sold the documentation alone to increase sales. This was the wink-wink-nudge-nudge aspect of the industry at the time and everyone knew it. So when Wordstar2000 arrived with a copy protection scheme everyone should have predicted its immediate demise. By the time the company removed copy protection it was too late to save it. One curiosity was the 1985 release of Wordstar2000 for UNIX! Wordstar would later evolve into Wordstar professional and Wordstar for Windows (which developed a cult following), but it was an uphill battle despite superior usability. The edge was gone.

Wordstar was my first PC word processor (although I’d used various other programs on my TRS-80 Model One before I had a PC); I had flashbacks as I read Dvorak’s words about that “no UNDO key.” I seem to recall needing to rewrite many mis-deleted sections of many essays because of this lack-of-feature.

I skipped right over Wordstar 2000 to WordPerfect, and, for a time in the late 1980s I had a small side-practice in teaching the blind how to use it with a screen reader (thus forever having “WordPerfect. Orem, Utah. USA” burned into my eardrums: that’s how the screen reader started each time WordPerfect was launched).

WordPerfect was slow to be replaced in the public service too; long after most everyone else had moved on, I’d still get WPD files from government and I kept LibreOffice on my Mac around specifically to be able to open them. It was as recently as a couple of years ago that I got my last one.

I expect that if I looked through the attic of our house I’d find floppy disks with Wordstar, Wordstar 2000 and WordPerfect files on them. I think it’s probably high time to rescue whatever’s on them before that’s no longer possible. Indeed, maybe it’s already too late.

This is the summer of cold brew coffee in Charlottetown.

In our house this was brought on by the introduction of a Japanese Hario Water Brew Coffee Pot, ordered from Amazon in March. We coarse-grind up some coffee, put it in the filter sleeve, add cold water, and leave it in the fridge overnight. Twelve hours later we’ve got easy-drinking cold coffee.

This morning I had the chance to taste the new cold brew at Receiver Coffee; it’s in a whole different class. More like wine than coffee, I told Chris, the personable brewmaster. You should try it. Especially this afternoon, when the temperature peaks and it’s just what you need.

Because I had both a cappuccino and a flagon of cold brew, I’m a little bit over the top this morning. But in a pleasant way.

At this hour, Sonia Painchaud, an estimable musician, is playing on Victoria Row as part of the Franco Festival.

Alas she is playing to an audience of approximately nobody, give or take.

Which is a shame, because she’s really, really good.

You have another 20 minutes to seek her out.

I joined the PEI Writers’ Guild yesterday.

The workshop I attended – How to Get Published – was my second Guild event of the year (the first was the launch of J. J. Steinfeld’s book in January).

They are a weird bunch, those writers. But good-weird and interesting-weird, and, if I’m going to join something, better a society of writers than, say, the Chamber of Commerce.

Joining the Writers’ Guild is also another halfway step to declaring “I’m a writer!”

Advice from Warren Ellis if you’re attending Comic-Con, from his excellent weekly email newsletter, Orbital Operations:

If you’re going to San Diego, buy hand sanitiser, gallons of it, and some one-a-day multivitamin bombs, and lots of water. Don’t eat sugar. Carry loperamide and ibuprofen. User antiperspirant deodorant and pack more underwear than you think you’ll need. Avoid skin in all forms. Denounce the sun. Wear shades to prevent eye contact. Respect the fursona. Store your fluids. Go home. Sit in the corner of the room. Think about what you’ve done.

This seems like good advice for any conference.

And, indeed, for life.

Back in October of 2014 I made a presentation on behalf of the PEI Home and School Federation to the Prince Edward Island Standing Committee on Education. In the question and answer session after my formal remarks I had occasion to suggest that “the education system is not Walmart,” something The Guardian called out in their reporting on the session.

What I meant by the comment was that we are not consumers of the education system, we are participants in it: we are all as much learners as we are teachers. Education is not a commodity, it’s an experience, and one that demands participation, not simply consumption.

Walmart is certainly a useful place to go if you want to buy cheap socks.

But you don’t go there to become a better human being.

I have similar feelings about Facebook.

Deep in my heart of hearts I see the rise of Facebook as the go-to place to post baby photos (etc.) as representing a deep failure of we who were there at the dawn of the web to do better.

We naively thought that society would build itself into an army of DIY-friendly digital warriors, ready to spin up a server and configure a Drupal instance.

We were wrong, and I will bear the shame of that until I die.

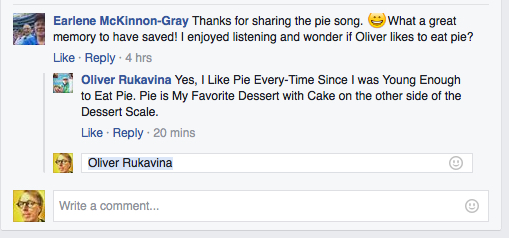

It’s difficult to be critical of Facebook because when you do so you risk being critical of all the innovative uses that are being made of it. The breast cancer support groups, and the this:

But for all that good, Facebook is more like Walmart than it is like that spot in the park around the corner where neighbours chat while their kids play. It is a marketing platform in the sheep’s clothing of the agora, and I find that conceit deeply disturbing.

This was driven home for me several years ago when I had lunch with a friend of a friend of a friend from Halifax. He was in the marketing game, and told me the tale of using Facebook from the other side, the side we baby-picture-posters never see, the side marketers use to push messages to finely-tailored demographics.

His client wanted to market beer, and so they used Facebook to push the beery message to something like “men in the Maritimes between 19 and 35 who had ‘liked’ a beer brand.”

All of a sudden the utility, for Facebook, of the “like” jumped out at me (I’m ashamed to say I’d never considered it in this light before): when we “like” something on Facebook we are part of a demographic sifting process. We are helping Facebook learn more about us so that they can package that information and sell it.

And it’s not just the “liking” that Facebook uses: it’s who your friends are, and what they “like,” and what you post, and what your friends post. And it extends beyond the bounds of Facebook itself: Facebook follows you around the web (those seemingly-benign and handy “like” buttons on websites: all part of the information gathering).

I use Facebook about as rarely as possible. I push my blog posts there automatically, occasionally make a comment on others’ posts, and that’s about it.

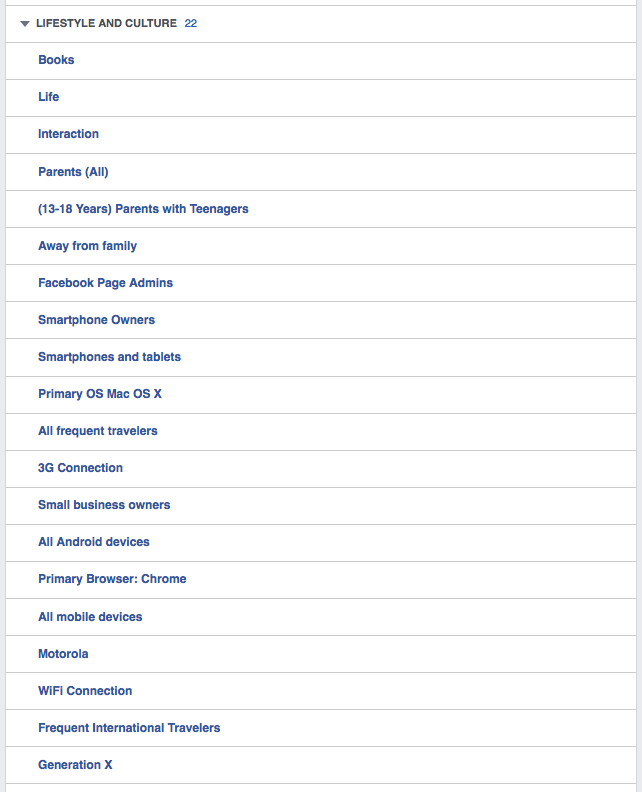

And yet here are Facebook’s “Ad Preferences” for me, based on what it’s been able to accumulate through its demographic dredging processes (you can find your own under Settings > Ads > Ads based on my preferences > Visit Ad Preferences).

That’s 100% accurate. Imagine if I was a more serious Facebook user.

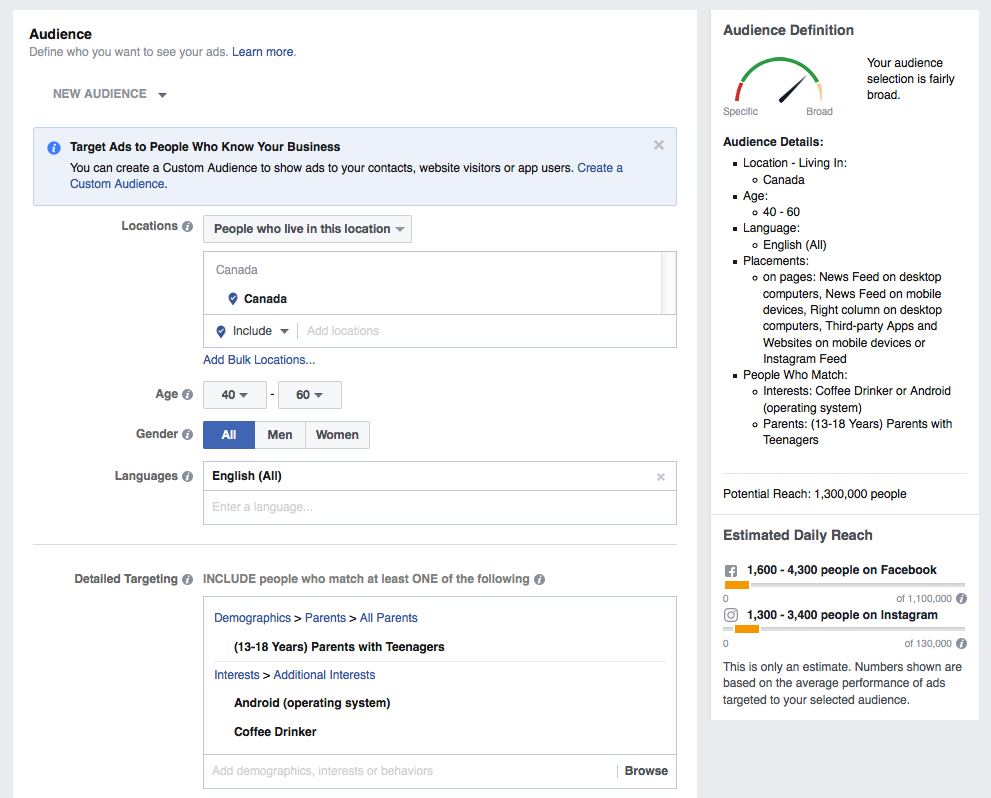

What we civilians seldom see is the other side of this equation (although there’s nothing preventing this: go and take a look).

Here, for example, is the start of a campaign I might launch to reach Canadians between 40 and 60 who drink coffee or use Android phones and who are parents of teenagers:

I don’t begrudge Facebook this, as this is its business, and it’s no more or less evil than any other enterprise.

What does bother me, though, is the popular notion that Facebook is somehow benign.

Progressive organizations routinely push the public to their Facebook pages, for example, with seemingly no critical reflection on how, in doing so, they are, in essence, requiring visitors to both deanonymize themselves and to further assist Facebook in its effort to target them (and their friends, and their friends’ friends).

And I am no better.

When I push my blog posts to Facebook and you click on them to read them here, you are helping Facebook target you, adding another data point to the big data pile.

I’ve been able to heretofore conscience this in the name of exposing what I write here to a wider audience.

But an odd thing has grown out of this: those that follow links from Facebook here and read what I write, will, more often than not, return to Facebook to leave a comment.

Which, to me, seems sort of like excusing oneself from a conversation and driving out to Walmart.

I’ve tried and failed to understand this behaviour. And I’ve grown more and more uncomfortable with the notion that my non-commercial rantings in this space gain a non-benign commercial quality when I push them to Facebook.

So this will be the last post I push to Facebook. And, for that matter, to Twitter, which, despite greater hipster street cred, is essentially in the same game as Facebook.

But what are you to do if you have been following along from Facebook or Twitter and now find yourself cast adrift?

Visit My Blog from Time to Time

There’s no reason you can’t visit ruk.ca in your browser whenever the mood strikes. It’s not automatic, but it’s the simplest solution.

Subscribe by Email

Every time I post something, you’ll get an email.

All you need to do is sign up once. If you choose to do this, be aware that:

- Subscriptions are run through FeedBurner, which is a Google-operated service, albeit a largely forgotten and untended one.

- I’ll know your email address and that you’re a subscriber.

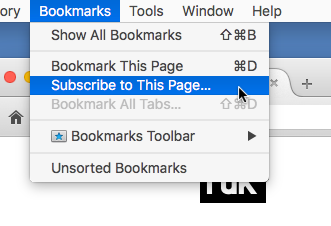

Use A Firefox Live Bookmark

Firefox lets you create bookmarks that are “live” inasmuch as they always have an up to date list of blog posts attached to them.

If Firefox is your browser, then this is as simple as going to Bookmarks > Subscribe to This Page when you’re on the front page of my blog:

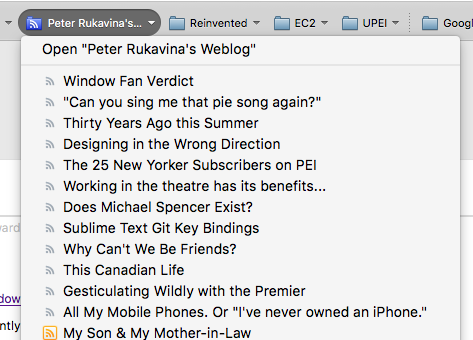

Once you’re live bookmark is in place, it will automatically be kept up to date with my new posts:

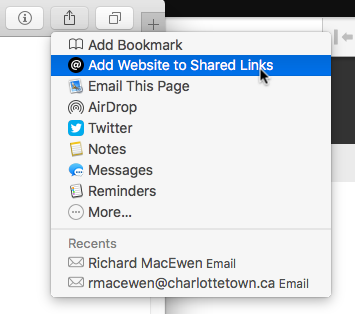

Use Safari Shared Links on Mac OS X

If Safari on Mac OS X is your browser, then you can click the “share” icon in the browser toolbar and select “Add Website to Shared Links,” like this:

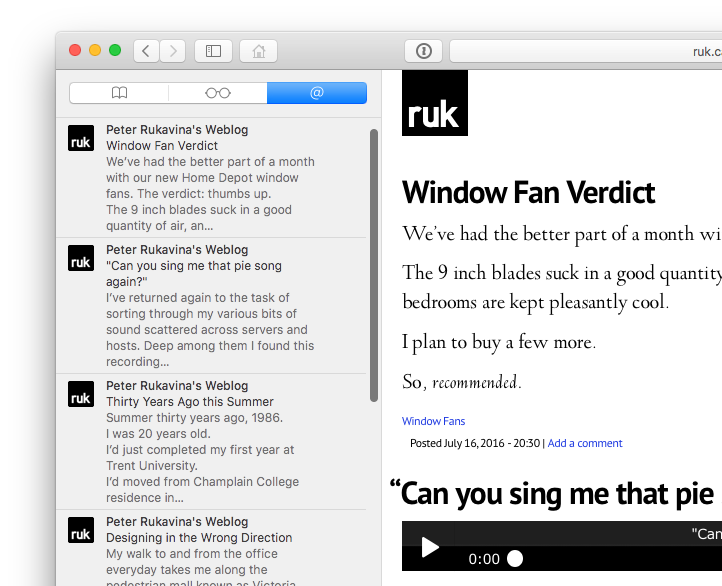

Once you do that then your Safari sidebar will be kept up to date with all the new posts like this:

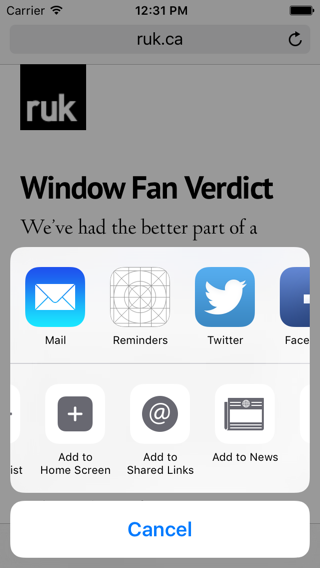

Use Safari Shared Links on your iPhone or iPad

Much the same “share links” functionality is available on iOS devices like the iPhone and iPad: just tap the “share” icon, then tap “Add to Shared Links,” like this:

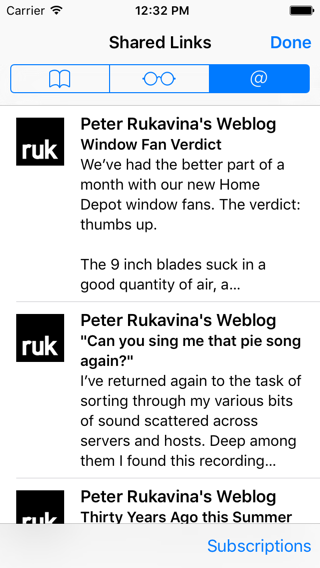

Once you do that, like on the Mac, new posts will show up in your Shared Links tab:

Set up an IFTTT Recipe

IFTTT is a website service that allows you to set up “recipes” — it stands for “if this, then that,” and that’s as good a description of the service as any. Setting up an IFTTT account is free (but, of course, as with all such “free” services, assume that there’s something in it for someone else at some point).

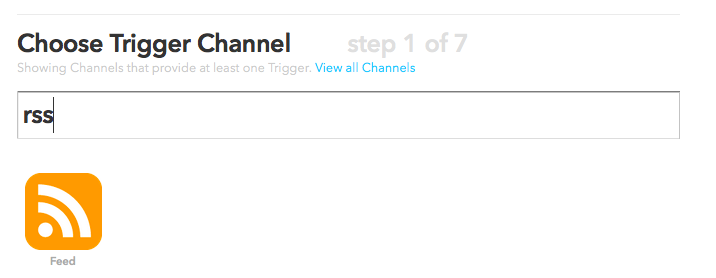

To set up an IFTTT recipe once you have an account, just click Create a Recipe, then search for the trigger channel called “RSS”:

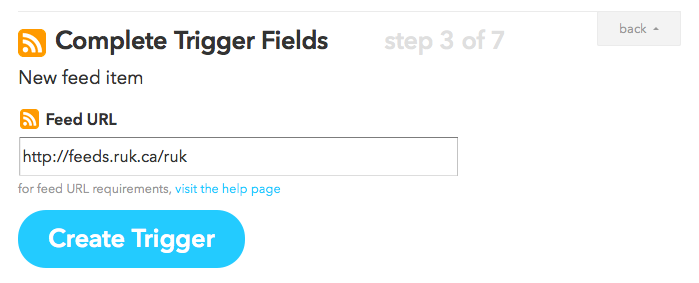

Select this channel, and then click “New Feed Item” and enter http://feeds.ruk.ca/ruk in the “Feed URL” field:

For the “that” part of the equation — i.e. how you’ll be notified — the world is your oyster.

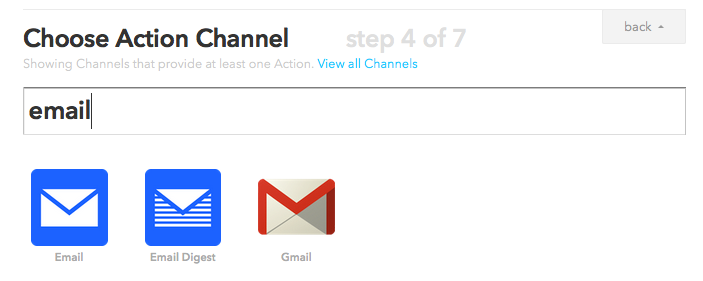

You could choose to receive an email message:

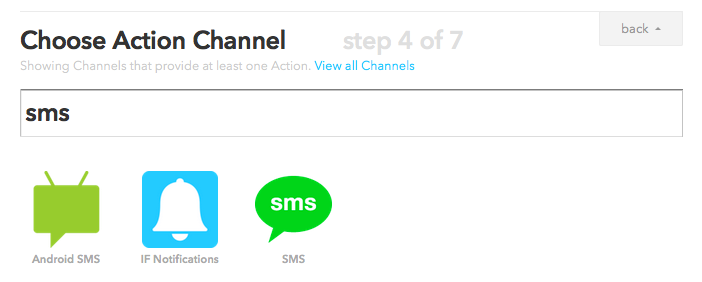

or a text message:

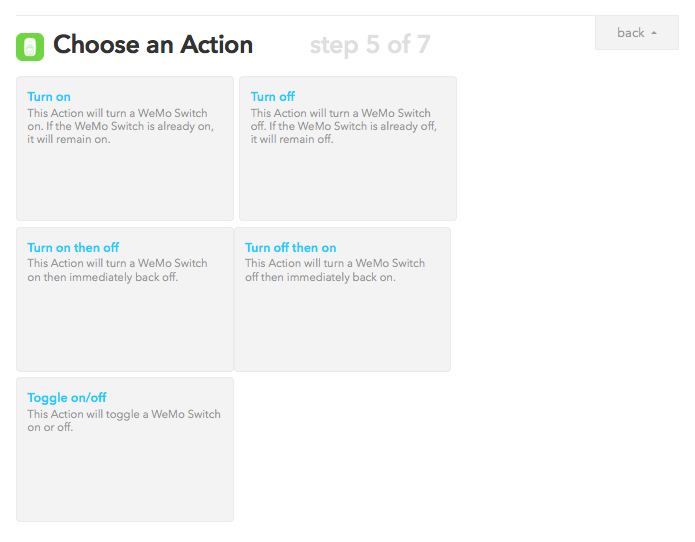

Or you could have the lights in your living room flash off and on:

Use an RSS Reader

Ten years ago this would have been my go-to suggestion, but while RSS is still alive and well and a vital part of many people’s information lives, it remains trapped in the nether regions of “it’s easy, just go do this and do this and then understand this and then do this other thing differently.”

That said, I encourage you to use an RSS reader if you can, as it’s a delightful, decentralized way to experience not only this website but many others.

You have two choices:

- Install an RSS reader app on your computer. On a Mac NetNewsWire is the venerable choice, for example, and it’s available for iOS as well. The advantage of using an RSS reader app is that you don’t have to sign up for anything: there are no third-party services to join, and all the magic happens on your computer or your device (although some readers have additional “syncing” features that you can optionally use to sync your RSS feeds across devices).

- Use a web-based RSS service like Feedly or The Old Reader. These are RSS readers you use inside your web browser. They tend to be free-to-use for some limited number of feeds, with premium subscription services on top of that.

No matter what RSS app or service you choose, the “RSS feed URL” you need to use for this blog is:

http://feeds.ruk.ca/ruk

If that address looks familiar, it’s because if you’re adding a Firefox “Live Bookmark” or a Safari “Shared Link,” you’re actually subscribing to the RSS feed, simply from within the more comfortable confines of your browser.

But this all seems like a lot of work…

I went to a PEI Writers’ Guild workshop called How to Get Published yesterday morning. I was simply curious; unlike most in the room, I don’t have a manuscript in my desk drawer waiting for the world.

One of the points driven home several times by the presenter was the importance of “building a social media platform” as an author.

Consider this withdrawal from social-media-pushing my doing the opposite of this.

As such, I’m aware that fewer people will read my words here.

But my words are not like Walmart. They are heartfelt. I spend a lot of time on them (it took me 90 minutes to write this post). I am proud of them.

They should demand a little work, at least on the head end, to be able to read regularly.

If this is the last blog post of mine that you read, I’m sorry; it’s been fun, and I will miss you. I hope you find another way in the door.

If any or all of the above confuses you, and you need help finding a replacement way to receive notifications, email me at peter@rukavina.net and I will help you until you’re set up properly.

We’ve had the better part of a month with our new Home Depot window fans. The verdict: thumbs up.

The 9 inch blades suck in a good quantity of air, and with the pleasantly cool nights we’ve been having our bedrooms are kept pleasantly cool.

I plan to buy a few more.

So, recommended.

I’ve returned again to the task of sorting through my various bits of sound scattered across servers and hosts. Deep among them I found this recording of [[Oliver]] when he was three years old, singing a song about pie.

Summer thirty years ago, 1986.

I was 20 years old.

I’d just completed my first year at Trent University.

I’d moved from Champlain College residence into John Muir’s house at 640 Reid Street in Peterborough.

Did I have a summer job? I can’t remember.

I was hanging out a lot at Trent Radio, I remember that. Listening to a lot of Suzanne Vega. Going to the Shish Kabob Hut. Taking my once-a-week turn at cooking supper for my roommates. Developing a crush on a girl for the first time.

My year at Trent had been neither a failure nor a success. I went in with no particular sense of purpose, and emerged mostly the same.

About this far into the summer I was debating whether to return to Trent or not, a decision that represented an opportunity to stake my own claim on life, but that was also tinged with a large amount of guilt for turning my back on, well, everything.

In mid-July it was all just theoretical. Stirrings.

By mid-August the die was cast.

I announced my decision to drop out by cowardly calling home at a time I knew my parents wouldn’t be there.

“Tell Mom and Dad I’m dropping out of Trent and hitchhiking out to the east coast,” I told my brother Steve when I called.

(In retrospect: what was I thinking?! What a phone message to receive from your son. I’m sorry.)

And that’s what I did. From Toronto to Montreal to Lévis to Rivière-du-Loup to Fredericton to Saint John. Across the Bay of Fundy to Digby by ferry, then by thumb to Pointe-de-l’Église and Yarmouth. Student standby on Air Canada from Yarmouth to Boston, Greyhound to St. Albans, and then hitchhiking to Montreal and back to Peterborough. How long was I gone? A week. Or two.

I must have phoned my parents back at some point. We must have had an animated conversation or two about my plans.

On my return to Peterborough I found that I’d received a partial scholarship for my second year at Trent, but by that time it was too late.

I’d staked my claim.

I am

I am