If you are reading the headlines of The Guardian newspaper 100 years on, you’re now making your way through the fall of 1916, and no more than a day or two passes without an update from the front in Roumania. Here are the headlines on those stories, working backward from November 3, 1916 to October 3, 1916.

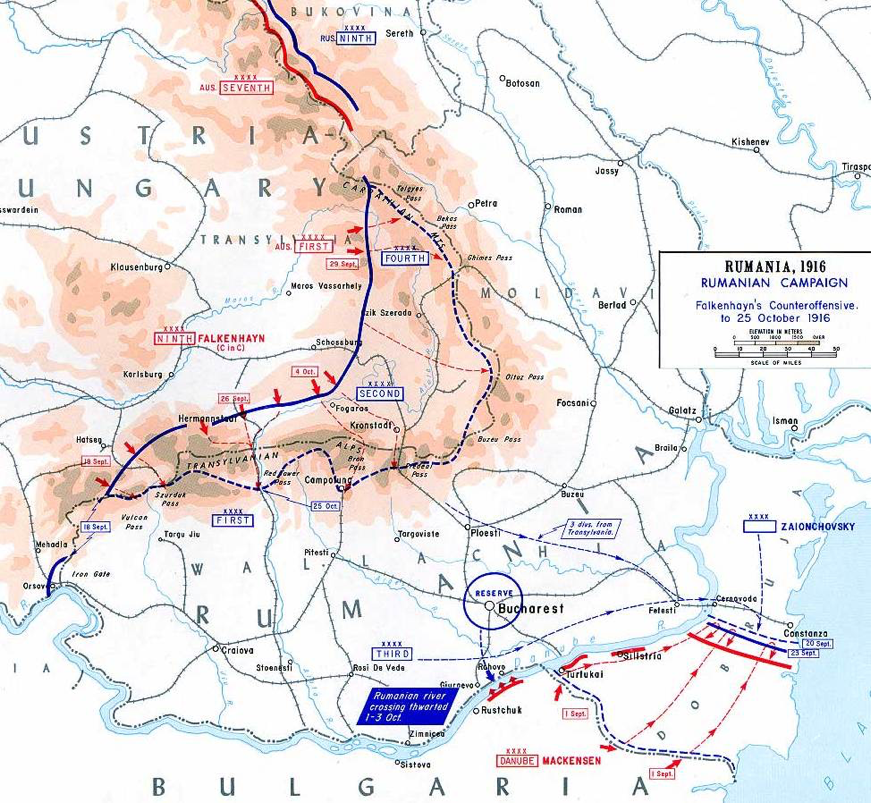

Wikipedia has a good review of Romania’s role in World War I, including this illustration of the borders and campaigns of this front:

With the end of October comes the opening of Victoria Row in downtown Charlottetown — the spine that connects my house to my office — to vehicles for the winter. Summer truly is over.

A few days ago, I mused aloud, both here and on Twitter, “Why do interview subjects say ‘that’s a great question’? I’ve never said that, and never understood it.”

I seems this was an unwitting lie; witness this interview I did just over a month ago with Global News in Halifax about the new edition of The Old Farmer’s Almanac:

To quote from the offending clip:

Interviewer: And you said as well that you’re from PEI, so you’re quite familiar with weather patterns and the way things kind of pan out here in Atlantic Canada with lots of snowfall. I know precipitation-wise, averagely, how much do we typically see here for snowfall?

Me: That’s a good question. I would say “a lot,” which reflects how much I know about the detail of the weather.

That’s a pretty good illustration of what Piya Chattopadhya described as “their brain is telling them to buy time cuz they don’t know what to say.”

I truly had no idea how much snow Prince Edward Island receives in the winter, and I truly did need that few seconds to come up with the best answer I could, which was “a lot.”

Et tu, self?

Barry Hicken served as Prince Edward Island’s Minister of Environmental Resources in the Catherine Callbeck Liberal government in the mid-1990s, a time when I was working with the province on the first iteration of its website.

Barry was well-regarded in this role, and well known, at least inside the provincial public service, for signing things with a green pen.

I don’t know why this fact about him stuck with me, but it did, and I’ve told the story of “Barry Hicken and his green pen” many times in the years since (I’m the kind of person who has conversations about things like ink and pens, where these things come up more than might be typical).

This morning I was sitting across from a friend in Casa Mia in downtown Charlottetown, and who should come in the door and sit at the next table over, but the selfsame Barry Hicken.

I couldn’t help but bring up the green pen, especially as I myself carry a green pen everywhere I go, one I purchased at MUJI in May in Berlin:

Barry smiled , reached into his pocket, and pulled out his own green pen. Some habits never die.

He then related how his write-in-green-pen system started: when he became Minister, he asked everyone in the office if they had a green pen. When the universal answer was “no,” he replied, “okay, nobody start” and then set down the rule that only he was to use a green pen. As a result, everyone in the department knew that when they saw something in green pen, it had come from the Minister.

Brilliant.

This morning on Twitter I asked “Why do interview subjects say ‘that’s a great question’? I’ve never said that, and never understood it.”

The question brought some interesting responses from journalists themselves, the questioners-being-praised (I’ve corrected some spelling errors to protect the innocent):

Dave Atkinson, freelance journalist:

gives you about seven seconds to think of a real answer. It’s more verbal punctuation than anything.

there are also a bunch of conventions in “tape/talks”, that don’t exist in real conversations. “Well, host-name, blah blah blah…”

I’ve also heard it used in a “oh god, I’ve been asked this so many times” kind of way.

Piya Chattopadhya, CBC Radio and TV Ontario host:

generally their brain is telling them to buy time cuz they don’t know what to say

Steve Rukavina, CBC Montreal reporter (and my brother):

it’s usually a pretty clear signal to me when I’m interviewing that they have no intention of actually answering the question

Kerry Campbell, CBC Prince Edward Island reporter:

I think politicians & bureaucrats told to do that as part of media training. Trying to butter up interviewers? Sound conciliatory?

I remember when the training started to include “say the interviewer’s name as often as possible.” I could live without that

Jessica Doria-Brown, video journalist for CBC Prince Edward Island:

They say it because they think it will butter you up. Instead, it often comes off as condescending and smarmy.

Taken in sum, there’s pretty clear guidance for we-the-potentially-interviewed to simply stop doing this.

You have been warned.

One of the most helpful services offered by our provincial government here in Prince Edward Island has always been Island Information Service.

By calling the easy-to-remember 902-368-4000 telephone number, I can talk to a friendly, helpful, knowledgeable information specialist who can help me navigate the complex thicket of the bureaucracy.

Except that now I can’t.

When I call that number now, rather than a friendly voice on the other end, a robot answers the phone and asks me to navigate a telephone tree: “for tax questions, such as property tax, deed registry, HST and pensions, press 2,” and so on.

Setting aside the wicking away of the helpful personal service, this approach is fine if your query happens to fall into one of the 5 options offered. But citizen questions are often more complicated than that, and it’s difficult to tell which bureaucratic box to tick. Talking one-on-one with Michelle or one of her colleagues would always result in an answer; tapping to the robot can quickly get frustrating.

But even setting that aside, robots don’t always work like they’re supposed to. Humans sometimes don’t work too, but with robots it’s often a binary breakdown — they work, or they don’t — rather than the “I’m having a bad day and aren’t as pleasant as I usually am” way that humans tend to degrade.

This was my issue today: I phoned Island Information Service to get information about how to get a voluntary ID for [[Oliver]]. I dutifully pressed 4 and then 2, and the robot told me I was being “transferred to Access PEI.”

A pause. And then “the number you have dialed is not in service; please check the number and try your call again.”

Oh no.

Systems are fallible — I’ve made a career out of managing their fallibility, so I know this perhaps better than most. But because I can only talk to a robot, I can’t report the issue: pressing 0 to speak to an operator doesn’t work. There’s no “to report an issue with this system” option. There are no search results on the government telephone directory for “Island Information Service.”

And so I’m stuck.

And thus I pen this bug report here, with hopes that the robot will read it and take corrective action.

And maybe bring Michelle back?

Eastern Graphic publisher Paul MacNeill’s column this week is a well-worded call for humility and humanity in journalism and politics both. Paul writes, in part:

Weekly I have the luxury of picking a topic and, more often than not, railing against some government action or lack thereof. When compared to e-gaming or PNP it is obvious not all controversies or scandals are created equal. This space has been far ahead of the curve in arguing for strong measures to deal with our fiscal issues and capacity, educational excellence, regional cooperation, size and focus of government and rural integrity and the demographic challenge we face.

Could some of the arguments be more nuanced or subtle? For sure. But many, if not all of these issues, enjoy a higher level of public awareness in small part because of these ramblings.

Fifty years ago former Island Premier Alex Campbell said in an address focussed on regional cooperation that “such complex concepts as these are very easily simplified, and even more easily promoted; but they are awfully difficult to translate into specific forms of co-ordinated action.”

Those words hold true today. Complex topics can be dramatically simplified in 600 words. PEI is still a leader in promoting regional cooperation. Wade MacLauchlan is doing everything he can to move the file forward, but winning change has as much to do with the willingness of your dance partner as anything else. If Nova Scotia or New Brunswick don’t want to dance, maybe it’s time we look for another partner.

I appreciate, particularly, the invocation of Alex Campbell’s advice, advice that essentially boils down to “ideas are easy, implementation is hard.”

One of the things I encounter frequently in my work in the non-profit world, is the lack of recognition of this fact: there is a common belief that if something is “right,” it should be implemented, and that any barriers to its implementation are barriers introduced by people who simply cannot see the “rightness,” or, worse still, are actively supporting things that are “wrong.”

No more so is this true than in public education: I’ve had scores of one-on-one conversations with teachers, principals, public servants and politicians and, almost universally so, their take on public education is significantly more progressive and enlightened than the education system we have on the ground would suggest. It is not for lack of ideas or inspiration that this is the case: it is because the public education system is a complex system, and we’re not very good, collectively, at changing complex systems. Systems thinking is a rare skill; there are not many who can see the forest for the trees, and even fewer who have any skill at convincing others that there is, in fact, a forest.

At this week’s meeting of the Learning Partners Advisory Council one of the members used the metaphor of “steering the ship” by way of suggesting one way of characterizing the council’s role in learning in Prince Edward Island. I suggested, as an alternative, that we regard learning as a flotilla not a single ship, and that our influence could, at best, be seen as an ability to nudge, not steer.

I think that’s what Alex Campbell was saying, in a different way, 50 years ago, and what Paul MacNeill ruminated on this week: in the grander scheme of things, being convinced of the rightness of your cause is insignificant compared to the challenges of understanding the point of view of those who disagree with you, and understanding the interplay between the components of the system you hope to change.

When my friends [[Olle]] and [[Luisa]] last moved house, in 2014, I was proud to have some of my letterpress work featured in one of the real estate photos taken to help sell their apartment:

This fall it was time for them to pick up and move again, and I was proud again to have some of my work lurking in the background of one of the real estate photos, through the door on the right:

Outside of their apartment-sales value, these photos are, for me, a lovely time capsule of Olle and Luisa’s housing epochs; I spent many happy hours in apartments 2014 and 2016 both, and look forward to spending time in the next one.

A few weeks ago, on Oliver’s birthday, we took a drive up to Georgetown to see the Spanish galleon that was in port. As we walked from the parking lot, along the wharf, to the ship, I noticed a rectangular net in the water, tethered to the wharf, about 400 square feet. I wondered what it was.

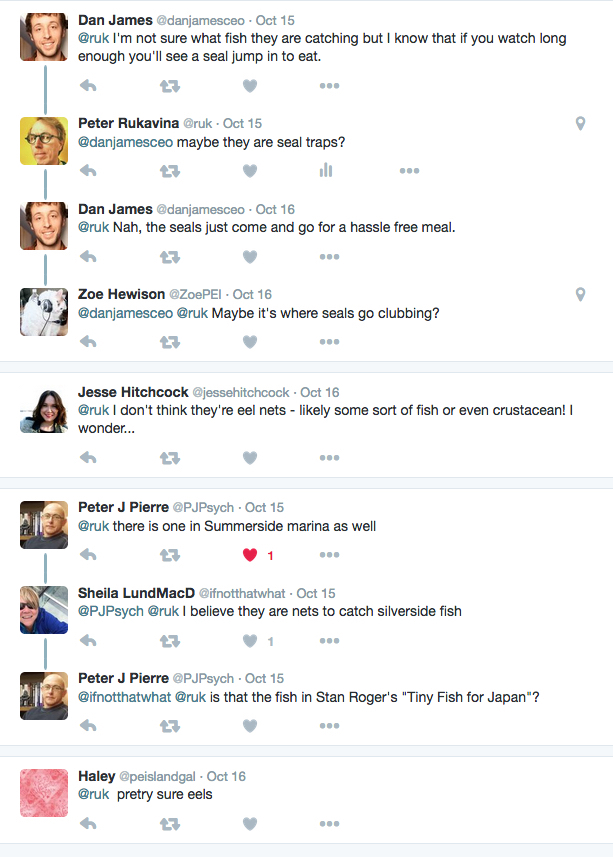

Then, last week, I noticed a similar net tethered to the end of Confederation Landing Park here in Charlottetown:

And yesterday, from the bridge of the Isaac Newton docked at the wharf in Charlottetown, I spotted another net tethered to shore just off the area where gravel is piled after being unloaded from barges:

I asked my Twitter followers what these nets might be, and received some helpful replies, including a report of similar nets in Summerside:

This morning I resolved to get to the bottom of this, and I phoned the main number for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans here in Charlottetown. I talked to a helpful person there who was able to confirm the theory put forward by Sheila Lund-MacDonald on Twitter that these nets are part of the commercial silverside fishery, the season for which opened on October 1, the same day I first spotted the net in Georgetown. I was given the number for the DFO person responsible for this fishery, and talking to that person allowed me to fill out the story.

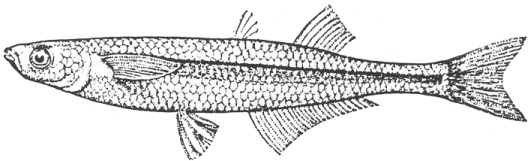

Silverside is a variety of fish that, these days, is fished commercially to use as lobster bait. The fish that are caught during this fall season, running October 1 to December 31, will be frozen and used as bait during the spring lobster season. A 2009 Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat paper describes the species:

The Atlantic silverside (Menidia menidia Linnaeus 1766), is a small-bodied (length < 12 cm), short-lived fish which is widely distributed in brackish and salt waters from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Florida. In its distribution, some Atlantic silversides overwinter in offshore waters but in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, at least some also overwinter under the ice in bays and estuaries. Silversides are commonly reported to form a substantial portion of the fish community in the coastal habitats they occupy including the bays and estuaries of the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Silversides reproduce in spring with eggs deposited in the intertidal zone, attached to vegetation or to the substrate. From sampling of fall fisheries in PEI, age 0 fish had a mean length of 85.5 mm and a mean weight of 4.6 g, while age 1 fish had a mean length of 113.9 mm and a mean weight of 11.2 g, with generally little size overlap between the age groups. Most (97%) of the silversides sampled were age 0, with the remainder being age 1. Age-2 silversides have not been reported from the few samples collected from the fisheries in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Silversides feed on small planktonic and benthic organisms. Fish-eating birds and fish in estuaries and coastal waters prey on silversides.

The paper goes on to describe the state of the silverside fishery on Prince Edward Island at that point:

In Canada, the silverside fishery is concentrated in Prince Edward Island with low and occasional landings reported from Quebec. The Canadian reported landings between 2000 and 2008 varied between 200 and 650 t, and represented 98% of the total commercial fishery landings for the species in eastern North America.

The PEI silverside fishery showed peak reported landings in the late 1970s, was low in the 1980s and the early 1990s, and began a sharply rising trend in the mid-1990s (Figure 2). The increase in landings coincides with an increased number of licences and the elimination of individual licence quotas. Silverside fisheries are concentrated in Kings County in eastern PEI with 86.6% of total landings since 1973. At the present time, an unknown but likely major part of silverside harvest may be kept for the fisher’s own use, or sold to other fishers. In either case, the harvest may be unregistered in the statistics system.

The modern silverside fishery began in PEI in 1973, first with seines, and in the following year, with traps. This fishery primarily supplied a Japanese food market, but sales subsequently shifted to the U.S., where fish were used as food for birds in zoos, and as angling bait. In the mid 1990s, the PEI silverside market largely shifted to supplying bait in the local lobster fishery. Prior to this change, the market was intolerant of sticklebacks mixed as bycatch with silversides, so trap catches were often released because the catch could not be sold. With the increased demand for the bait market, tolerance of stickleback bycatch increased, so trap releases due to excessive stickleback bycatch became less frequent.

And this 2000 fisheries management plan for the species contains an illustration of the fish:

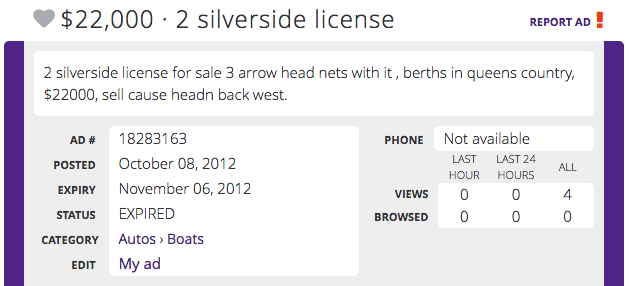

It seems the fishery can be lucrative, given the $22,000 price for a couple of licenses back in 2012 in this UsedPEI.com ad:

So, mystery solved.

I am

I am