I’m no great fan of the fast food industry, but A&W deserves a hat-tip for its Beyond Meat Burger and the way they’ve presented it.

I remember, many years ago, going through the drivethru at the Burger King in Charlottetown and ordering a “veggie burger.” What I received was a bun with a tomato slice and lettuce. Technically qualified, but hardly satisfying.

I stripped down the child-carrying bicycle trailer we inherited from Erin Bateman and Dave Atkinson, added three six foot lengths of pine 1x3, four carriage bolts, and some #12 wood screws: presto, a bicycle cargo trailer, ready for Sobeys.

As the son of a geologist, and as someone with a soft spot for underdog monuments, the Charlottetown Boulder Park has always been an object of fascination for me. It was born the same year I was, in 1966; now, 52 years on, few people seem to know anything about its origins; indeed it’s easy to miss that it’s there at all, given the various renovations to the yard of the Hon. George Coles Building that have lessened the prominence and accessibility of the boulders.

I decided, given this, that I was the right person to shine light on the park and its history.

My inspiration came from a mention in Mita Williams’ weekly email newsletter of the utility of populating Wikimedia Commons with the images of Wikipedia and Wikidata entries that are missing them; this led me to the Wikimedia Commons app, and, in turn, I learned how Wikidata, Wikimedia Commons and Wikipedia are linked together.

To lay the groundwork for this project, I started by taking out of cold storage a set of images of the boulders in the Boulder Park and the plaques describing them; I uploaded these to Wikimedia Commons, and tied them together with a Category called Charlottetown Boulder Park.

Next, I created a Wikidata entry for Charlottetown Boulder Park, along with Wikidata entries for each individual boulder (here’s Alberta, for example). I attached the Wikimedia Commons images I’d just uploaded to each boulder, along with its geographic location and, where possible, made each an “instance of” the type of rock it’s composed of.

I then edited OpenStreetMap and added links to the Wikidata entries to each of the boulders I’d plotted on the map several years ago.

Finally, I set out to author a Wikipedia page, the most daunting task of all, as it was completely new terrain for me, and something cloaked in mystery, with seemingly arcane rules and style requirements.

It turns out that there’s a remarkably helpful set of resources to help the new Wikipedia author, starting from Wikipedia: Your first article.

Wikipedia requires sources to be cited, so my first task was to find documentation for the history of the Boulder Park; I had help in this regard from the Public Archives and from Robertson Library, and this helped me find my way to articles from The Guardian and the Evening Patriot from 1966 that documented the opening of the park. I found an additional, contemporary reference in The Guardian–a column by former editor Gary MacDougall–in a full-text search of the paper on the library site:

- The Guardian, September 2, 1966: page 1 and page 3

- The Evening Patriot, September 2, 1966: page 2

- The Guardian, September 6, 2014: page 13

With these references in place, I set out to create the page: I wrote a paragraph about the history of the park, a paragraph about its opening, and I filled in the details of the “info box” template for parks. I added a table with information about each boulder (using the Wikimedia Commons images I’d created earlier), and I added an embedded OpenStreetMap map showing the location of each boulder.

Once I’d finished, double-checked everything for typos and style, and had some trusted friends review it with fresh eyes, I clicked “Publish” and the new article went into a queue for review; there was a box at the bottom of the article at this point alerting me that this could take up to 5 weeks, as there were 2000+ articles in the queue at this point.

The review happened much more quickly than that, though: within 24 hours I got an email alert telling me that someone had updated the article, and, sure enough, the history for the article showed that it had passed the review and was now public.

So, ta da, here it is: Charlottetown Boulder Park in Wikipedia.

I finished up the linked by connecting the OpenStreetMap boulder park relation and the boulder park Wikidata entry to the Wikipedia page, thus nicely knitting all the various manifestations of the park together.

But I’m not done yet!

I’ve been in touch with the operators of the Street Eats food truck that’s set up this summer on the edge of the Boulder Park, and they’ve agreed to provide a home for a printed guide to the Boulder Park, so my next step is to make one.

Thank you to Mita for the inspiration, Olle, Simon, John and Ed for the reference help and proofread, and to Graeme for the Wikipedia review.

This YouTube video combines my love of public transit with my love of renaming things and my love of institutions having a bit of fun. It also involves football, but that’s an unimportant side-issue.

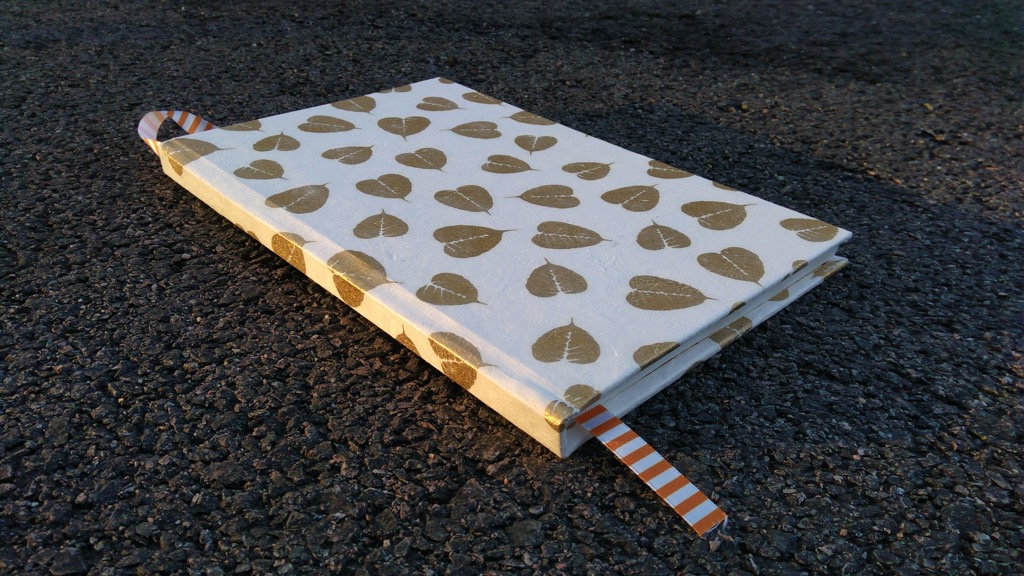

Today’s project was to take the hardbound book I made last week and make another one, improving some of the parts that went sideways in that first iteration. Up

Here’s what I ended up with:

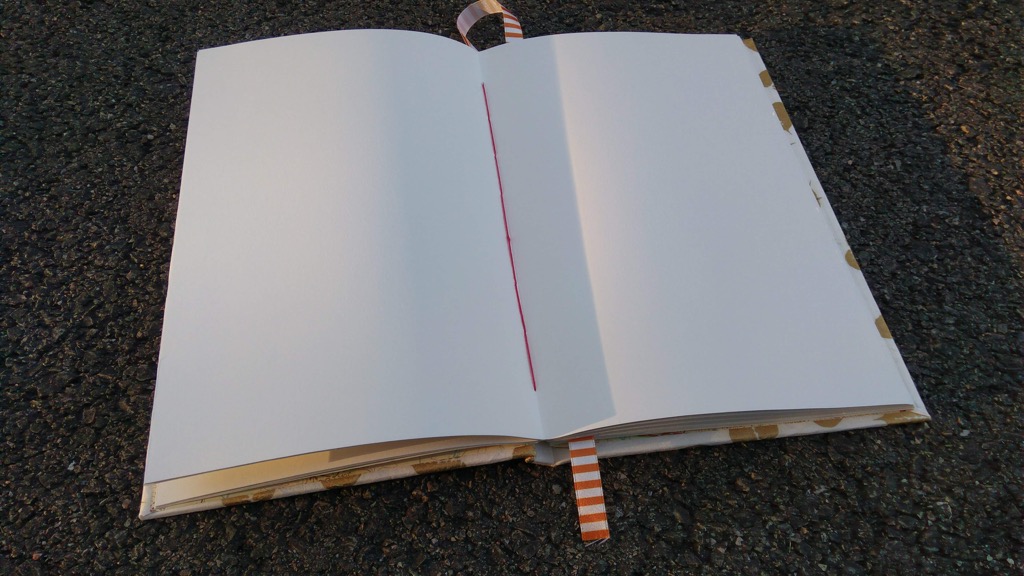

The paper is from a pad of 70 lb. Strathmore drawing paper I purchased at Michaels; it’s a step up from the Staples copier paper that I used for my coptic stitched book.

While not as toothsome as the St. Armand paper I used in the last version, it has the benefit of being slightly less precious-feeling (Catherine said “the paper is so nice I don’t want to draw on it” about the last book; this is not a good quality for a sketchbook to have). It was a bit of a challenge to wrangle the paper out of the pad along its perforated edges, so I suspect this isn’t a paper source I’ll go back to. But it did the job.

The stitching, in red cotton thread, went much easier, partly because it was my second time, and partly because the thread didn’t get bunched up nearly as much.

The cover stock and book board beneath it are the same combination I used last time, but I got the spacing of the covers and the spine right this time, meaning that the book opens and closes very pleasantly.

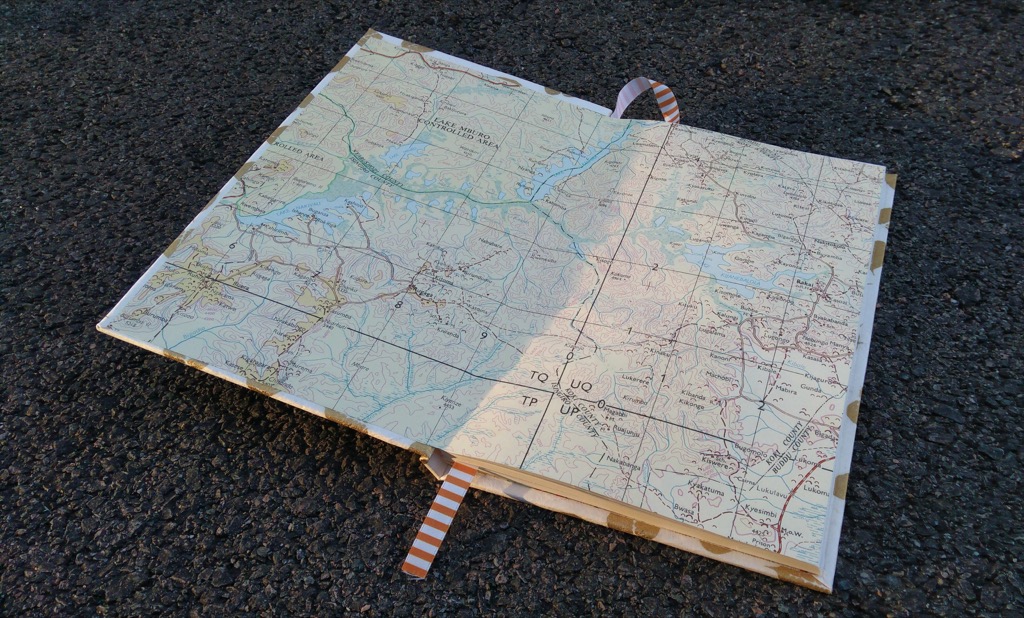

For the endpapers I used a map of Mbarara, Uganda that I rescued from the University of Calgary Library in 2014. I felt bad about cutting up the map; but otherwise it was destined to live a live of solitude on my paper shelf, and at least now parts of it will have a new life.

As you can see in that photo, I was liberal in my ribbon-marker length; truth be told, when I cut the ribbon I thought “this is way, way too long.” It wasn’t. I need to singe the end of the ribbon lest it fray; I’m afraid to do this, as there’s some chance the book might burn to the ground if I’m not careful.

There is still much, much to get better at. My glue-management is still dreadful. I haven’t mastered the art of cutting reams of paper with a knife (I was formally trained to cut single sheets of paper only). I need to become better at right angles. And bone folder use.

I really could throw it all in and do this all the time, though; it’s lovely work to practise.

If you can overlook that York University Libraries appears to refer to itself as YUL, also the IATA airport code for Trudeau Airport in Montreal, I believe you will find Interviewing at York University Libraries staggeringly useful. Especially if, say, you’re about to interview at York University Libraries.

All daunting experiences should be so lucky to have such a helpful field guide.

My friend [[Olle]] doesn’t blog very much, but when he does it is, as a result, doubly special.

Yesterday he wrote about a trip to Amsterdam and, in particular, to Mediamatic, which is a Dutch institution that I’ve followed agog, from afar, for many years.

After this journey into aesthetics, we relocated to a new had very good pizzas at Mediamatic ETEN. Elderflower lemonade! Someone speaking Danish tended the bar. “Take a look around!” Aquaponics gardening in a greenhouse with colored LEDs. “Oh, all food here’s vegan.”

There are plans afoot for [[Oliver]] and I to return to the Netherlands at the end of August, and I hope that we can make Mediamatic one of our destinations.

One of the advantages of having a partner in the fibre arts industry is a ready supply of various and sundry threads. Courtesy of same, I sewed up a new text block yesterday, using some red cotton thread that Catherine gave me to sew together signatures made from sheets of 70 lb. Strathmore drawing paper.

One of the challenges I face in learning about bookbinding is a striking inability to think clearly in three dimensions; it’s no wonder that my vocations to date have been firmly rooted in the comfortable two dimensional plane of printing.

No more so was this true than in my attempt to sew together a coptic-stitched book today, helped along by this video how-to.

Coptic binding is simple, at its heart, but it requires the ability to retain a three dimensional picture of where you’ve been, where you’re at, and where you’re going, and this is something almost beyond my abilities.

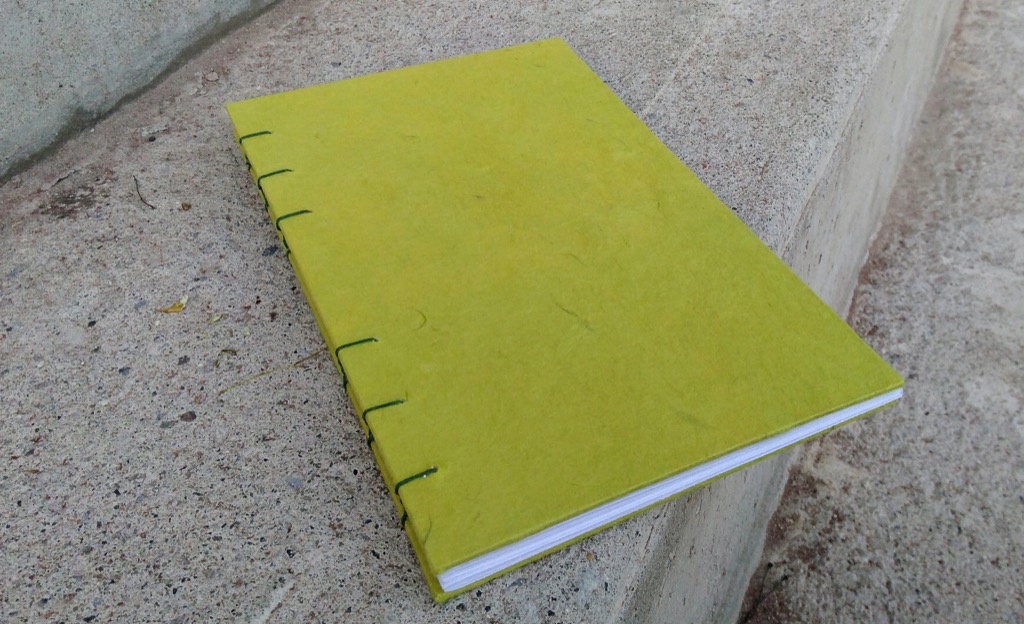

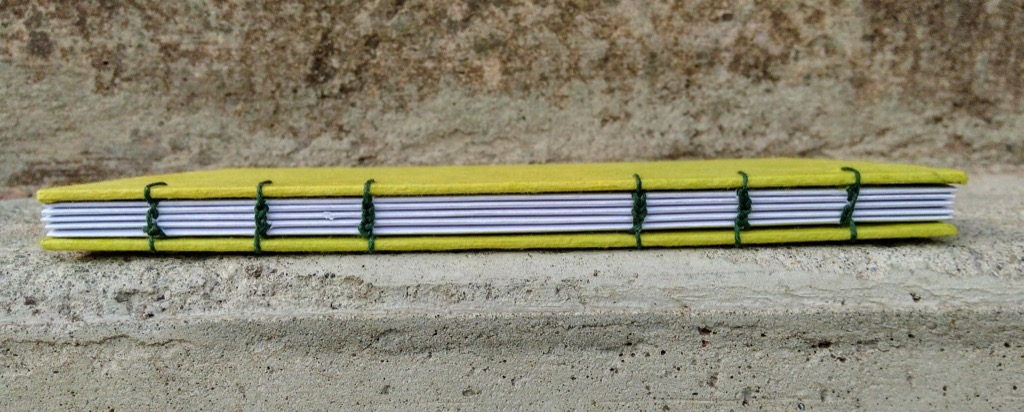

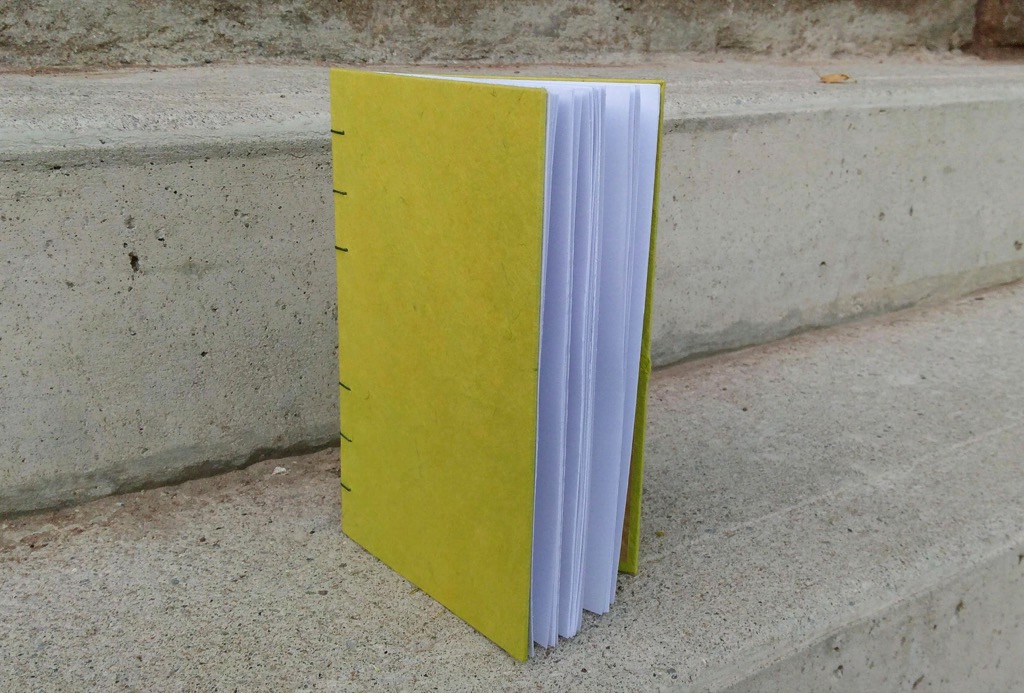

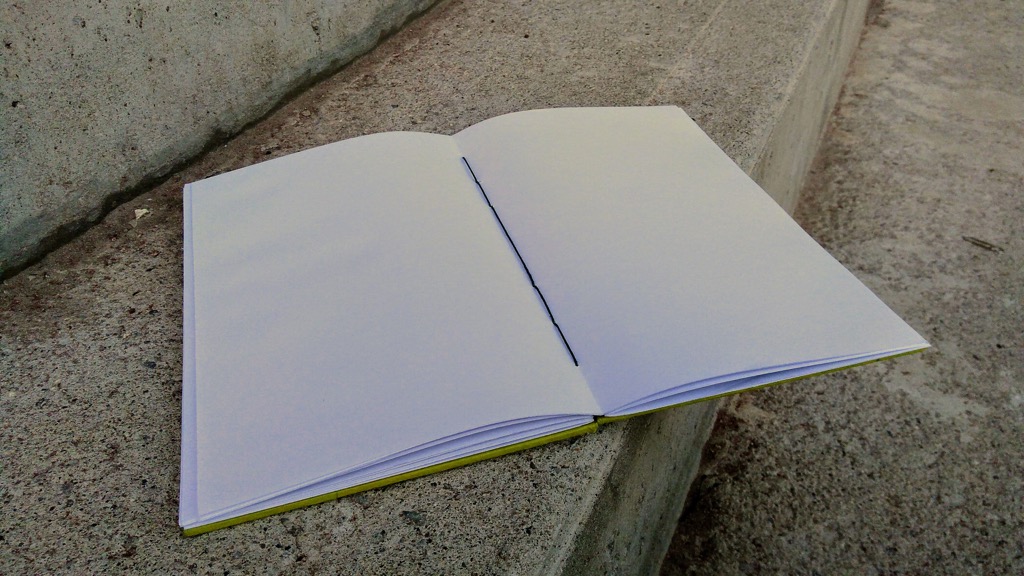

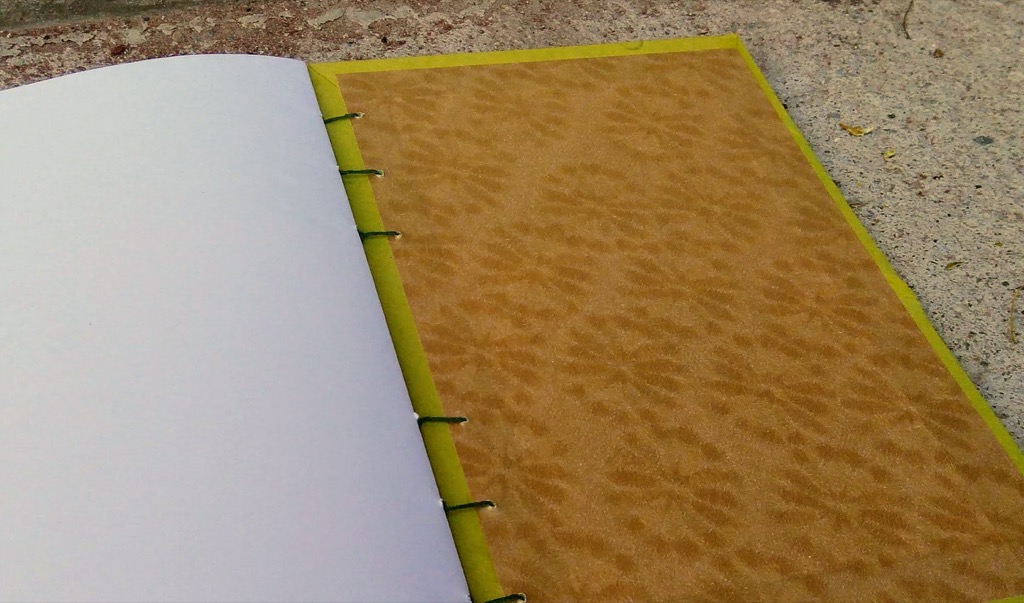

But I kept at it, and here’s what I made:

My stitching went off the rails a few times; most of the time I managed to wrangle things back into order, but there are a couple of gnarly bits there. Coptic stitching is a struggle to maintain just the right amount of tension in the cord to hold things pleasantly together, without making it tight enough to tear nor loose enough to flop around. I didn’t win that battle completely, and my book is a little too floppy for my tastes.

My big error in judgment was opting to use stock 20 pound printer paper for the inside pages; after dealing with the substantial living organism that is St. Armand machine made paper, constituted from rag not wood, stitching through Staples paper feels horrible and unforgiving and deeply unsatisfying. Never again.

That all said, the book does lay open flat rather pleasantly–coptic binding’s strong suit–and I was proud of my ability to translate the stitches on the video into stitches in reality.

I made the covers from the same sheet of “display board” I used to cover my hardbound book earlier in the week; I covered them with some lovely, thick green paper that Catherine gave me last year. The inside covers are Japanese paper from the same odds-and-sods lot I picked up at The Ikebana shop. The stitching is with green linen cord I purchased at the NSCAD art supply store a few years ago.

The only way I’m ever going to crack this thinking-in-3D nut is with practice, so I’ll make more coptic-bound books until I get it down.

I am

I am