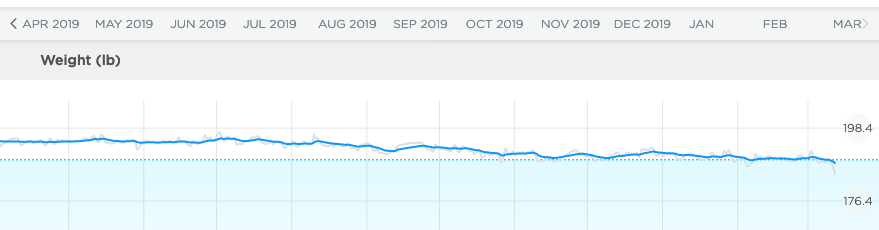

A year ago this morning I weighed 195 pounds. This morning I weigh 184 pounds.

I know this because I’ve been weighing myself on a wifi-enabled bathroom scale for the last year:

That I weigh 11 pounds less year-over-year is not so much an accomplishment as a side-effect, more an accumulation of accidental fitness, shifting from eating lunch out to eating lunch at home, the prostrating effects of grief and, over the last week, an unnatural dip due a nasty bout of gastroenteritis (that I do not recommend, at all, as a weight loss program).

The most noticeable effect of this, day to day, is that I’ve been having trouble keeping my trousers up.

For years I wore trousers with a 38 inch waist and a 30 inch inseam (we Rukavina boys were gifted long torsos and short legs from our father); six months ago I realized that I could wear trousers with a 36 inch waist, at least in Levi jeans. And that helped. But I still had trouble keeping my pants from falling down.

I found the solution this morning–duh!–was simply to punch another hole in my belt, an inch upstream from the last one. Now–ta da!–my trousers stay up just fine.

The GI bug manifested itself first in Oliver: he barfed all over the living room on Sunday afternoon, and developed a low-grade fever, chills and a headache. Once I’d dealt with coronavirus fears–it’s a breathing thing, not a barfing thing, it turns out–I settled him into a routine of small sips of water and pieces of toast and we hunkered down for his recovery.

Then, on Monday, 24 hours after Oliver, just as it seemed like we’d turned a corner, my own guts unloaded. Fortunately not all over the living room. And I developed the same symptoms as his.

Tuesday I was more catatonic than I’d been in forever: there were times that I literally could not get out of bed. Oliver was well enough by this point, fortunately, that he could be relatively self-contained as long as I rousted myself to bring him a glass of water and a piece of toast every once in a while.

By Wednesday we were both tentatively on the mend: we kept down a bagel and peanut butter, and some plain rice. I folded the mountain of clean laundry that had been accumulating on the laundry room floor.

Today Oliver’s home for the day–his last, I’m hopeful, before returning to his regular routine–and I’ve dipped my toe back into the office. I had some cereal and a cup of coffee for breakfast and, well, so far so good.

All in all not something I’d wish on anyone, but compared to the coronavirus, a walk in the park.

I didn’t leave the house for three days and already had touches of cabin fever and could not watch another episode of Seinfeld.

Fourteen days of self-isolation? I have newfound empathy for the self-isolating around the world.

CleanTalk, the comment spam filtering service that I use to allow me to reasonably maintain the ability to accept comments here, reports that in the last week it filtered 51,821 spam comments and allowed 12 legitimate ones.

Most of the spam comments were SQL injection attempts from hosts in the Russian Federation and Germany.

While CleanTalk is doing an excellent job at filtering–it let through exactly zero spam and filtered out exactly zero ham–it’s exhausting to consider the amount of the Internet’s capacity that is taken up with attempts to undermine it.

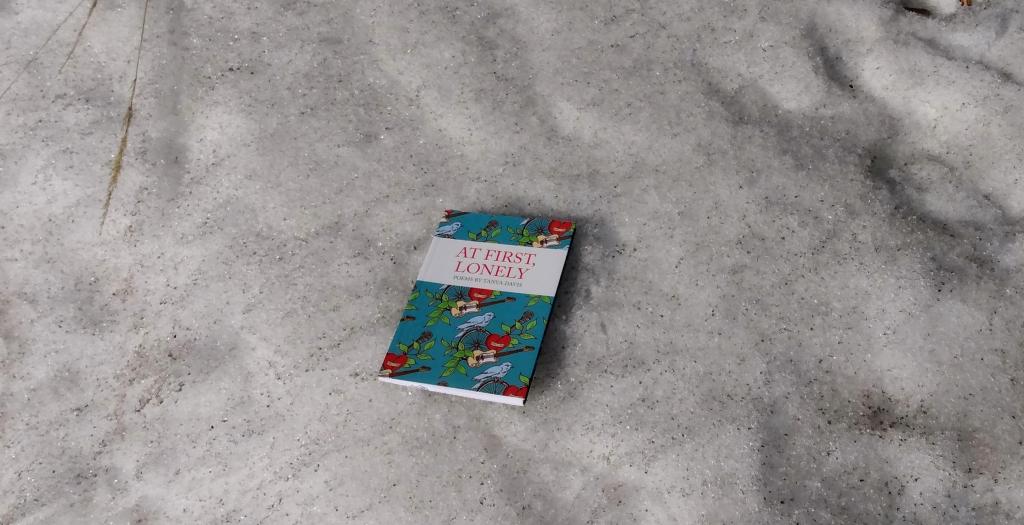

Went poetry shopping with Oliver.

Went poetry shopping for the first time ever.

I’ll take a Tanya Davis, to go, please.

And I’ll plant it in the snow.

Short of ironing my shirts on those weeks I’m on the job in New Hampshire—a habit I learned from brother Johnny—I have never been an ironer. And I’ve absolutely never ironed pillow cases. But when life hands you entropy, you fight back with every bit of negentropy in your arsenal.

Twenty years ago last week my friend Catherine Hennessey started blogging.

And then she kept at it for three years, eventually writing more than 200 posts. Enough to turn into a book.

It’s always given me great satisfaction that Catherine was one of the people who invented this new medium, and that I was there to help.

Congratulations, Catherine!

I do so aspire to a fashion sensibility.

Back in April, at a campaign event in Summerside, I snapped a quick photo of Alex Tyrrell, leader of the Green Party of Quebec, wearing a smart black shirt and yellow trousers and I thought “that’s who I want to be.”

But I fear that I don’t have what it takes.

No patience for shopping.

No ability to shop.

Depression-era frugality baked deep into my DNA.

The component parts just aren’t there.

But you know what I can do: retire the grey sweater.

I’ve been wearing this grey particular sweater for a long, long, long time.

Here’s my first recorded photo of it, from June 6, 2006–14 years ago!–a selfie of me and Oliver at Legoland in Denmark:

Here it is in our 2014 family Christmas photo, 8 years later:

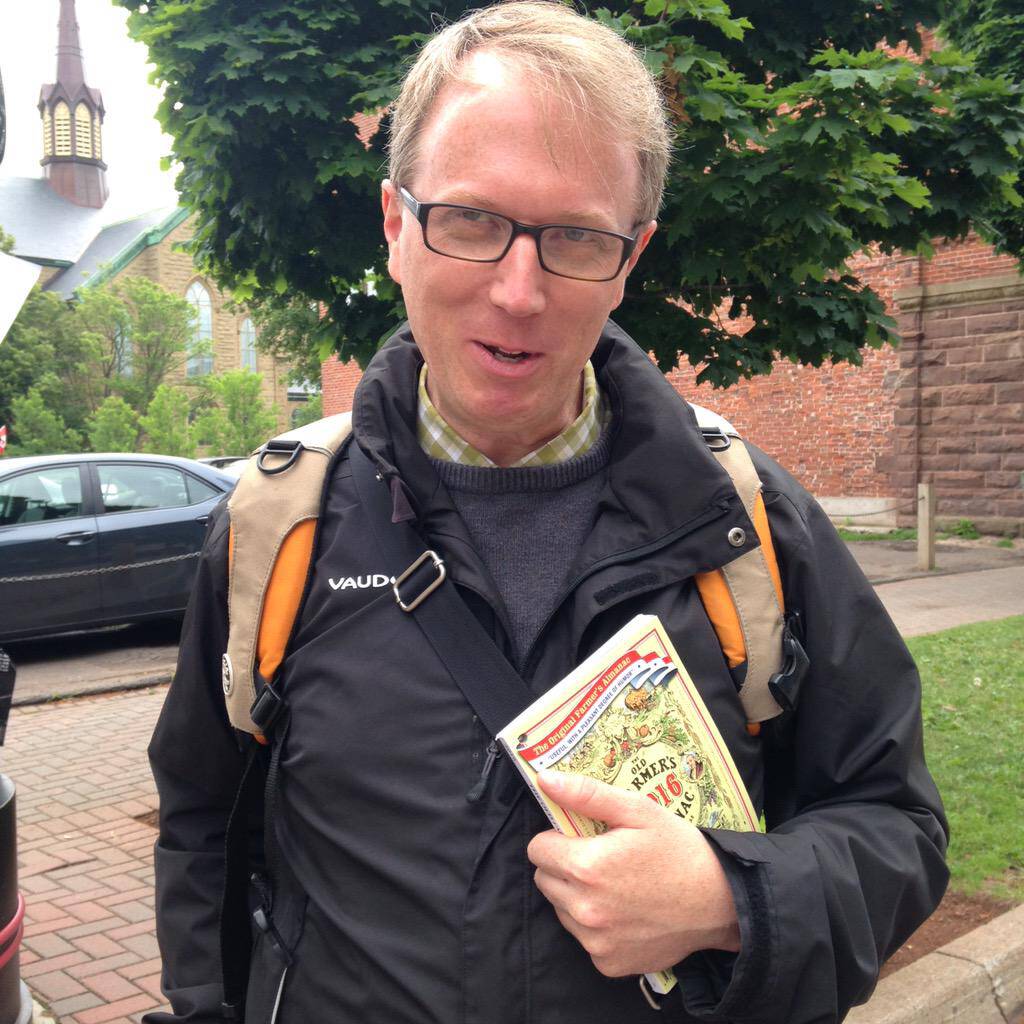

Here’s an appearance it made in 2015, while I was promoting The Old Farmer’s Almanac:

And two years later, in front of the late, lamented My Plum, My Duck:

It’s a Denver Hayes-brand sweater, which means it came originally from Mark’s Work Wearhouse, which isn’t even called that any longer.

And while it once may have been acceptable attire, I’ve been overlooking the fact that there’s been a hole in one of the underarms for several years, and that there’s been a hole in one of the arms for several months.

While both of these are, technically, darnable, there’s a larger issue that the sweater, due repeated use, has become a formless grey void:

It’s my very favourite sweater.

It’s comfortable. And familiar. And warm.

But it’s time to say goodbye.

I stopped at KC Clothing this afternoon while I was on my way to a plasma donation and found two new sweaters to replace it.

So that’s what you’ll see me around town in. At least until the snow’s gone and summer sets in.

My frugal DNA won’t allow me to actually throw my faithful grey sweater away, so it will go into the “things to wear while fiberglassing a kayak” section of the closet.

Goodbye old friend.

A commendable example of living the obligation to explain from they of Hundred Rabbits; in part:

Our head was previously equipped with a solar fan, an accessory not suited to offshore waters. It came with the boat. With this fan, waves that washed over the deck would sometimes come spilling inside — not ideal. When in the head, in your private time, the last thing you want is to have a salt water shower.

All reports from his adoptive family are that Ethan is thriving and is much-loved. I do miss him so, especially those times he would climb up on my lap, despite his 65 pounds, and fall asleep.

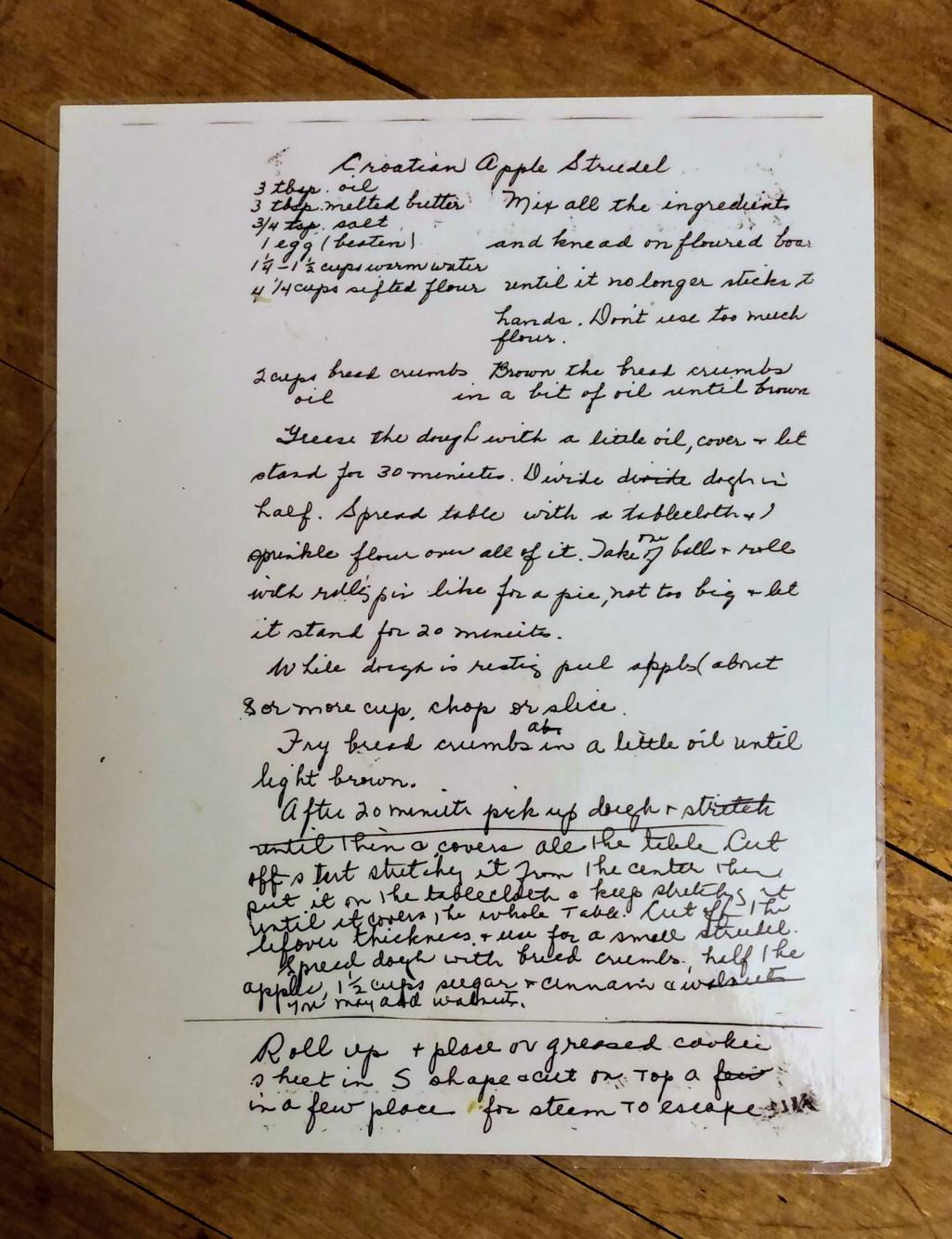

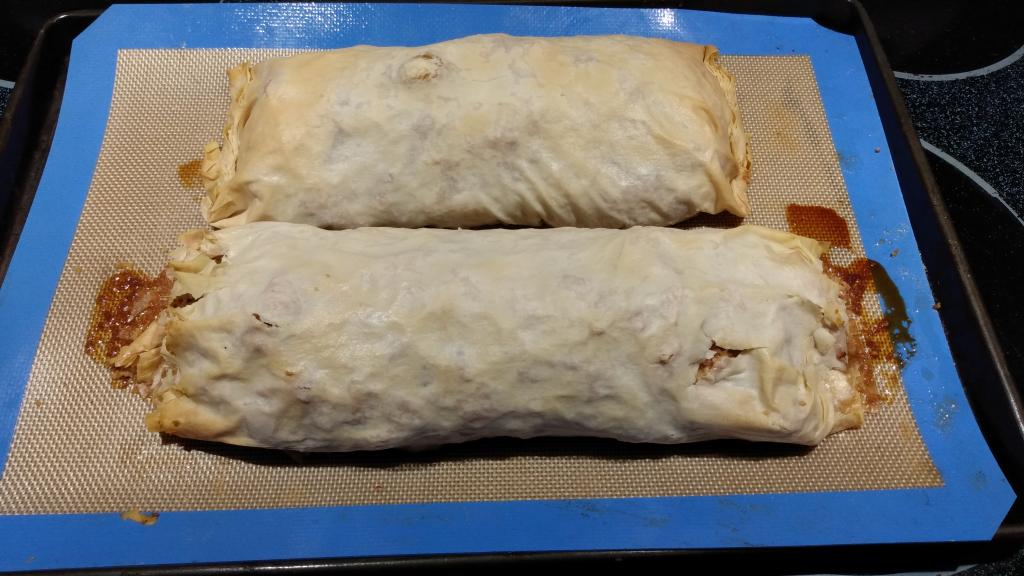

My grandmother Nettie’s signature dessert was her apple strudel. It was served at all family occasions. Not only was it very good, but it was made from phyllo pastry that she made herself, from scratch, a miracle of patience and technique.

As I was going through Catherine’s things a couple of weeks ago, I came across a laminated copy of Nana’s strudel recipe stuck between a couple of cookbooks on the bookshelf. I set it aside, with thoughts that I might make it myself someday; opportunity presented itself this weekend when we were invited to the multicultural potluck lunch tomorrow at St. Paul’s Anglican Church. We will be the Croatian contingent.

Setting out to actually make the strudel this evening, I realized that Nana’s recipe was very heavy on the phyllo making and very light on the strudel making. This makes sense: when you’re making your own phyllo, the strudel part, time- and complexity-wise, is insignificant.

I wasn’t up to making phyllo from scratch, however, and so I was left to follow her scant instructions at the very end for the strudel, and to wing it from there. I had the benefit of having watched her make it many times, but that was over 30 years ago.

I’m rather proud of the result. It’s demonstrably apple strudel. I could have used more phyllo, and kept the apples away from the edges, but the result is pleasantly tart, with a hint of cinnamon and walnuts, and while nowhere near as good as Nana’s, it’s a credible homage.

If you are a parishioner at St. Paul’s, there will be a dozen pieces up for grabs tomorrow morning.

,

,  ,

,  ,

,

I am

I am