Catherine died a month ago today, just around this time of night.

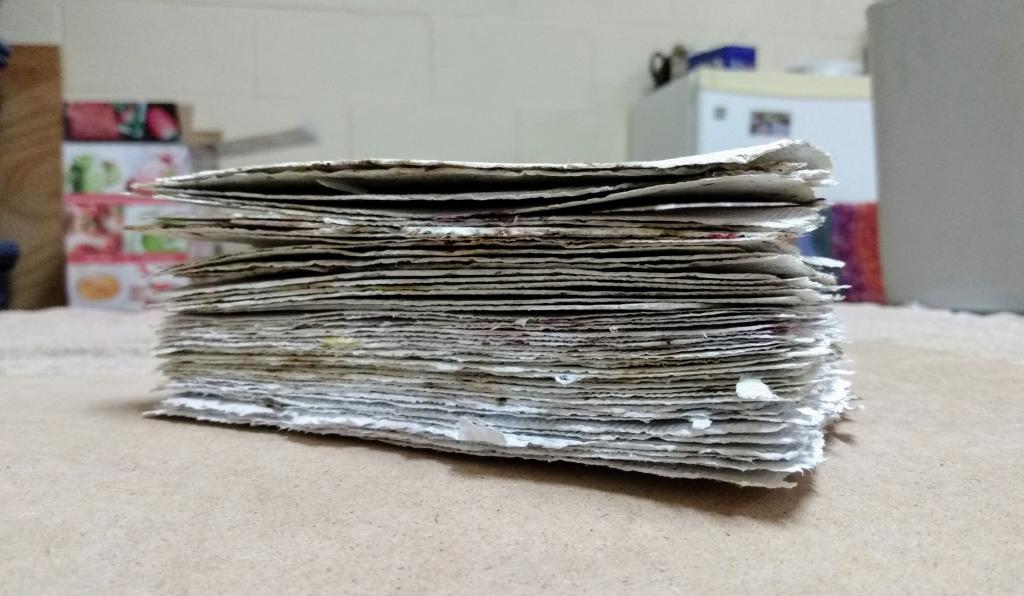

Over the last several weeks I’ve been spending time in her studio making paper using the letters and cards and flowers of condolence we’ve received.

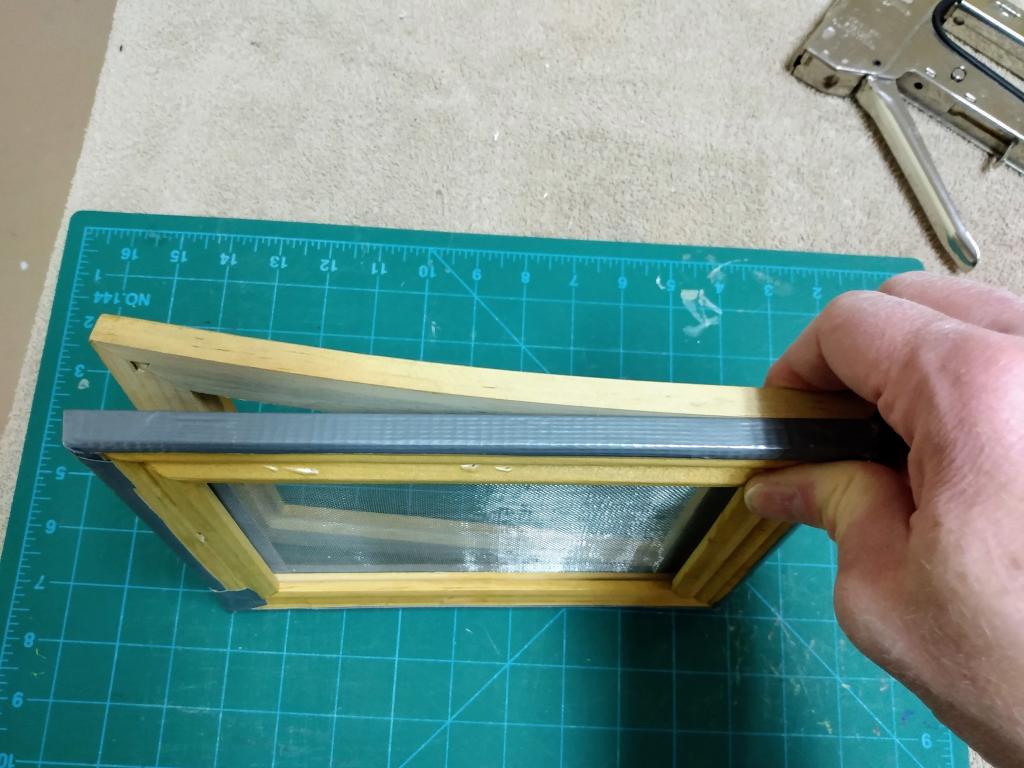

After experimenting with various tools, I set on a small mould and deckle that she had made herself from a couple of simple picture frames and some window screen. This needed some repairs; of course I found all the tools I needed to affect them in her cupboards.

I finished the last of 50 sheets of paper this afternoon.

Every piece is unique. There are bits of sealing wax smeared through some, and bits of thread and plastic in others. Some show patches of fountain pen ink. All are raggedy and irregular and dramatically imperfect. She would love them.

The best part of the entire exercise is that when I ironed each sheet after drying the room smelled like fresh-cut flowers.

My next Herculean task is finding new homes for Catherine’s tools and books and for the carefully curated stash of fabric, yarn, and thread she assembled over a lifetime of making. I’m happy I was able to undertake one last project amidst all that.

Beyond Catherine’s longstanding fundamental discomfort with the notion that, for the most part, I earned money and she didn’t, which we came to terms with as much as it’s possible to come to terms with, the only financial schism in our 28 years together was a home equity line of credit that we secured against our house at 100 Prince Street when we purchased it in 2000.

By lucky happenstance we were able to pay cash for our house when we bought it; it needed substantial renovations, though, and we didn’t have the cash for that, hence the line of credit, which was akin to a mortgage, but with a better rate, and much more flexible terms.

After the initial round of renovations, it was my intent that we pay off the line of credit and shut it down over the course of 3 or 4 years; I’m genetically programmed to be averse to debt of any sort, and I wanted it gone. Things didn’t work out that way, in part because other major expenses arose, and in part because Catherine and I disagreed as to the nature of the instrument: I treated it as a sacred crucible to be used gingerly; Catherine treated it as an infinite pile of free money. Neither of us was right-headed about it, really, and so discussion of the line of credit and its disposition became an occasional source of tension between us. Never enough to be a truly big deal; never not enough to truly recede into the background.

The Monday after Catherine died we got a letter from TD Bank, in the regular course of their affairs, informing us that the life insurance rate on the line of credit would be going up. This came as a surprise to me because I’d completely forgotten that we had life insurance on our line of credit. So I called the bank, found out that we did indeed, filled out some paperwork, and waited.

Wise financially-inclined friends, as well as CBC Marketplace, cautioned me that because line of credit insurance is “underwritten at time of claim,” I should be prepared to have the claim denied because that essentially means that the insurer does the investigative diligence at the end of the process, not at the beginning, as is typical with other types of life insurance.

And so I wasn’t banking on this happening. Which was okay, because I’d never been banking on it happening.

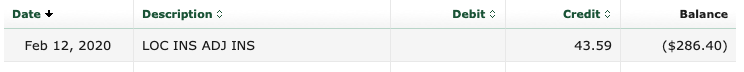

Today, though, I got a call from my friendly banking associated at TD Bank in Charlottetown telling me that the claim had been paid and that, once everything went through the wash, TD Bank owes me $286.40.

When I related the broad strokes of this story to my friend Dave last week, his reaction was “so Catherine was right!”

I hadn’t thought about it that way until that point, but Dave pegged it: our line of credit was much more infinite-pile-of-money than sacred-crucible.

She was right.

The hard fact of life and death means that Catherine will never know this, and that’s a shame.

For the first time in 25 years, I am debt free.

And while I would, in a heartbeat, give that up to have another hour with Catherine, it’s also an unexpected bit of good news in a run that hasn’t had a lot of that.

The Taylor Swift documentary Miss Americana is fascinating, and so much more than the concert film I was expecting

The heart of the film is Swift’s 2018 decision to come out publicly against the antediluvian Tennessee Republican candidate Martha Blackburn and, in so doing, coming out of the apolitical female country singer closet she’d been living in her entire career.

The film is also Swift’s rumination, on the brink of turning 30, on gender and fame:

It’s a lot to process because we do exist in this society where women in entertainment are discarded in an elephant graveyard by the time they’re 35.

Everyone’s a shiny new toy for, like, two years.

The female artists that I know of have reinvented themselves twenty times more than the male artists. They have to. Or else you’re out of a job.

Constantly having to reinvent. Constantly finding new facets of yourself that people find to be shiny.

Be new to us.

Be young to us.

But only in a new way, only the way we want.

And reinvent yourself only in a way that we find to be equally comforting but also a challenge for you.

Live out a narrative that we find interesting enough to entertain us, but not so crazy that it makes us uncomfortable.

Swift’s The Man explores the same themes, and the film contains compelling scenes of her working out the lyrics for the song.

Like me, my nieces are big Taylor Swift fans. I’m happy that they set on her as a role model; there’s a lot to be learned from who she was, who she’s becoming, and how she’s reflecting on that transformation.

Tony needed a top-up for his Nissan Leaf during a meeting across the way this afternoon. How great is that he can fill up at our place!

This is going to drive Catherine’s ghost bonkers, but I think I might be coming around on microwave ovens.

I’ve never owned a microwave.

Sure, I’ve used one three or four times: a couple of times in the hospital, maybe a couple of times in a hotel room.

But I’ve always been deeply suspicious of them: fire, I have always said, is an element I can get behind.

A mysterious metal box that cooks food, but not containers? That’s voodoo.

Catherine never shared my deep suspicions: she kept a microwave in her studio, and would have eagerly added one to our kitchen had my veto not made this impossible.

On Sunday, though, I had supper with my physicist friends, the two people on Prince Edward Island perhaps best able to explain how microwave ovens work, and why I do not need to suspect them.

Microwave ovens, it seems, just make water vibrate, and when it vibrates, it heats up. And because food has water in it, the water heats up the food around it. That is all.

I’m reconsidering my position.

Stephen Fearing and The Sentimentals, As the Crow Flies.

I saw Fearing live at George’s Roadhouse in Sackville on October 18, 2014. Catherine had been diagnosed with breast cancer a few weeks previous; it was confirmed to have spread to her bones, and thus be incurable metastatic breast cancer, two days after I returned from Sackville.

That week I started an email newsletter to update Catherine’s friends and family; here’s what I wrote in my first message:

Apologies for moving so quickly from handcrafted individual emails to a mailing list, but I was beginning to lose track of who I’d told what about Catherine and her progress, and this seems like a way of doing so that’s sustainable, but without the publicness of a blog, which would make Catherine uncomfortable. Catherine has, however, bless this alternative.

I’m writing mostly because I need to write to process things – that’s what my blog is for, and with that off the table, I still need a way of processing things. So I apologize in advance if what and how I write sounds overly technocratic or emotionless; that’s how I’m used to writing, and I’m pretty sure if I just started crying I wouldn’t be able to get the details down as I want to.

I’m also writing to save Catherine the need to re-explain the ins and outs of her cancer to each of you every time you meet; that can be exhausting for her.

I’ll do my best to keep you all updated over the days and weeks to come; I won’t take it personally if you decide to unsubscribe (there should be a link to allow you to do that down at the bottom), as I can only imagine that getting frequent missives about the minutiae of breast cancer can be a trigger for some, and an annoyance to others. I won’t take unsubscribing personally, I promise.

For those of you that I’m emailing the first time, here’s what’s happened so far.

Catherine was experiencing some pain in her right breast, which prompted her to visit our family doctor, Peter Hooley. Dr. Hooley ordered a mammogram of both breasts, the results of the mammogram were concerning enough to prompt a follow-up mammogram and then a “core biopsy” – taking selected pieces of breast tissue so that they can be examined under a microscope for signs of cancer.

The results of the mammograms and biopsy showed evidence of cancer in Catherine’s right breast, and this resulted in a referral to Dr. Fleming, a General Surgeon, to talk about surgical options.

We first met with Dr. Fleming on September 25. His assessment at that point was that Catherine had treatable cancer in her right breast, but the left breast looked clear, and his recommendation, which Catherine accepted, was to move forward with a lumpectomy for the right-breast tumour: basically a targeted “cookie cutter” to cleanly remove the cancerous tissue in that breast.

The lumpectomy was scheduled for this Wednesday, October 22 and in the interim Dr. Fleming ordered a range of additional tests, all designed to determine whether or not the cancer had spread to other parts of Catherine’s body.

Breast cancer, we learned, isn’t all that much of a problem all by itself, localized to the breasts: it’s when it spreads – they call this “metastasizes” or “advances” – that it becomes a larger concern that can no longer be treated with a simple lumpectomy.

Over the past week, Catherine’s had a bone scan (a radioactive dye injection, 3 hour wait, and then a scan of the bones; cancer cells show up differently than regular cells in the scan), an MRI of both breasts (basically, a look at the breasts with more detail than the mammogram allowed), a lung/chest X-ray, a breast ultrasound, and a lot of blood work.

Her MRI was, according to Dr. Fleming, the test he was most dependent on to determine whether to proceed as planned: it happened just this past Friday, and within 20 minutes of leaving the hospital, Dr. Fleming was on the phone to Catherine with some initial findings.

The MRI showed that the cancer in the right breast is “multi-centric.” This means that rather than being a single removable tumour, the cancerous cells are in more than one “quadrant” of the breast (divide the breast into four neighbourhoods; if there’s cancer in more than one neighbourhood it’s “multi-centric”). This is important to learn because it means that a simpler lumpectomy is no longer an option for removing the cancer in that breast: the only option is a mastectomy (complete removal of her right breast).

The MRI also showed what may be a cancer in Catherine’a left breast, although this hasn’t been reviewed to the extent where it’s possible to make decisions about it yet.

And the radiologist reviewing the MRI also suggested that there may be “lymph node involvement” on the right side as well: when breast cancer starts to spread, it goes to the lymph nodes first, and so it raises a flag.

More concerning is that the bone scan showed evidence of what the surgeon called “increased uptake” (of the radioactive dye) in three locations: in Catherine’s hip, in her right femur, and at two locations in her spine.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the cancer has spread to Catherine’s bones: one thing we’re learning quickly is that while we might think of cancer diagnosis as Star Trek-like, it’s really more a synthesis of imperfect, indirect tests. So having bursitis in her hip might cause this “increased uptake” just as much as cancer might. However because of the femur involvement – Catherine’s never had an injury to her femur, so it’s unlikely that the increased uptake would be caused by something else – it’s not a good sign, and it’s these bone scan results that have caused the plan to suddenly change course.

The plan now is that in the next few days Catherine will have an MRI of her bones, which might (or might not) shed more light on whether the cancer has spread there. She will also have a CT scan of her chest, stomach and pelvis, also with a goal to determining whether it’s possible the cancer could have spread there.

Dr. Fleming also recommended that Catherine put off the surgery on Wednesday, for two reasons: first, the additional testing this week will tell him more about the left breast, and whether a double mastectomy would be recommended, and, second, it’s likely that the next best step would be chemotherapy, not surgery, and so he has recommended using the surgical time on Wednesday to outfit Catherine with a “port-a-cath”: this is basically a semi-permanent “shunt” that’s installed under her shoulder blade on the front, with a tube connected directly to a large vein that’s found there.

The port-a-cath allows chemotherapy drugs to be sent in, and blood to be taken out, without the need to find veins in Catherine’s arms or hands, and makes the logistics of chemo go much more easily.

So that’s the tentative plan right now: port-a-cath on Wednesday followed, likely, by the start of chemotherapy as early as next week.

Another thing we learned today is that cancer treatment isn’t really like an orchestra being guided by a conductor, but rather more like a series of soloists each specialized in a certain approach to cancer, with the best one for the current treatment running the case at any given time.

So, in other words, the reason we’ve had two visits with Dr. Fleming is because the plan to this point was surgical, and he’s a surgeon. Now that the plan looks like it might change, it’s likely that Catherine’s case will be transferred to a “medical oncologist” in the PEI Cancer Centre, and that the oncologist will pick up the baton and guide things from here.

Dr. Fleming, however, is still holding the baton for now, and he’s going to spend two hours in the hospital tomorrow morning requesting tests, conferring with the radiologist and the medical oncologist, and he’ll call us tomorrow with the results of his discussions, and an indication of when other tests will happen, and whether or not it makes sense to have the port-a-cath inserted on Wednesday or not.

Assuming that the course change is to chemotherapy, the details would be worked out with the medical oncologist, and a course of treatment developed, with a schedule of chemotherapy appointments over the next 3-4 months. Receiving chemo is incompatible with surgery, so if surgery were to happen it would happen after chemo.

We had a lot of discussion about what this means and whether it’s a good idea to wait on surgery and the basic message we got from Dr. Fleming is “if the cancer has spread to other parts of your body, it’s most important that we deal with that first.”

Dr. Fleming is a superb tactician: he spent 15 minutes with us diagraming the procedure for inserting a port-a-cath. But because he’s a surgeon, not a cancer specialist, he wasn’t particularly good at describing for us what chemotherapy will involve, what the schedule will be, how what the side-effects will be, and so on. We’ll learn about all of that from the medical oncologist.

What he also couldn’t tell us anything about is what Catherine’s prognosis is: when cancer spreads from the breast to elsewhere in the body, it is called “metastatic breast cancer” and it’s not considered curable, in the “we’ll go in there and get this out” sense. But it’s not a death sentence either: it’s possible to live with metastatic breast cancer as a “chronic condition.” Not forever, but for many years.

And that’s about all we know.

I may be writing this to you with what seems like a cool head, but my head isn’t really that cool, nor is Catherine’s. It’s likely that the life of our family got turned upside down today in ways we don’t completely understand yet, and it’s hard to have conversations about all of this without bursting into tears simply from the stress and confusion and complexity of it all, and the feeling of being amidst something completely beyond our control.

Many of you have called or emailed in the last couple of weeks, and I’ve appreciated that. If I’ve sounded a little distant and clinical about everything, it’s only because that’s my best refuge to keep from breaking down on the phone or in person.

For the crew that seized the bull by the horns and came over and made the good part of a backyard fence for us this past weekend, thank you: it was the #1 best thing you could have done to make Catherine’s life better this weekend.

Catherine lived for 1,914 more days after I sent that out.

Bill McKibben in The Guardian, When it comes to climate hypocrisy, Canada’s leaders have reached a new low:

Americans elected Donald Trump, who insisted climate change was a hoax – so it’s no surprise that since taking office he’s been all-in for the fossil fuel industry. There’s no sense despairing; the energy is better spent fighting to remove him from office.

Canada, on the other hand, elected a government that believes the climate crisis is real and dangerous – and with good reason, since the nation’s Arctic territories give it a front-row seat to the fastest warming on Earth. Yet the country’s leaders seem likely in the next few weeks to approve a vast new tar sands mine which will pour carbon into the atmosphere through the 2060s. They know – yet they can’t bring themselves to act on the knowledge. Now that is cause for despair.

I am

I am