Catherine died tonight at 9:20 p.m.

I was at her side, joined, a few minutes later, by Oliver, my brother Mike and my mother.

Catherine died gently and peacefully, and on her own terms.

As she lived.

I was chatting with Catherine’s doctor about changes in her breathing—it seemed like it was slowing, and changing cadence and, to be honest, I was panicking 5 or 6 times a minute when it seemed like the next breath wasn’t going to come.

“I’m kind of an expert on Catherine’s breath,” I joked.

“It’s okay,” the doctor told me.

These breathes may be different but, it seems, they are not typical of final breathes. So I relaxed. A little.

Later on I did the calculation: 15 breathes a minute over 28 years is about 13 billion breathes since we met.

So I am an expert.

I’ve missed a lot of them—work, travel, grocery shopping, watching The Office.

But I’ve never had a more intimate relationship with someone’s breath. I know its sound and its shape and its feel. I’ve been inside her breath and outside her breath and joined with her breath. Annoyed by her snoring, delighted by her singing.

As I write I am listening to her breathing beside me. If I knew drum notation I could write it down: it’s new music; she is not struggling, but the breath also doesn’t come easily.

This time after treatment ends remained a mystery that nobody would talk about over these five years that Catherine’s been living with cancer

“We’ll cross that bridge…”

“It’s different for every person…”

How many times have I googled “how do you die from breast cancer,” with hopes that some kind soul had written a helpful play by play. I found lots of Mayo Clinic bulleted lists about dry lips, but not very much written by humans, for humans.

Which is no surprise: who wants to dwell here. There are precious few epic poems written about the Frankfurt Airport transfer lounge. For much the same reason.

Conservation of dignity gets in the way, too. I spoon-fed Catherine fish chowder for supper tonight; even telling you that seems like revealing a confidence. After all, this is, not really, my story to tell.

But there is a reason that cancer memoirs end prematurely. Or with a “before she could finish this manuscript….” epilogue written by the partner.

And so the story of this time seldom gets told.

And perhaps we don’t have the language to do it justice: the time for battle-words is done (if it ever had a place at all). There are no longer villans or heroes (if there ever were). Everyone knows the ending.

It is a slow and unusual part of the story that we’re uniquely untrained to hear: familiar breath becomes unfamiliar breath becomes familiar breath again, for a moment, and then.

Archdeacon John Clark writes about the future of the church.

John and I had a long and helpful conversation on Saturday: at one point we shared how, at our core, we are both in the metaphor business. Our framework is different. But we often end up at the same place despite this.

(In his acceptance speech for the Mark Twain Prize, Dave Chappelle touched on a similar notion: he can find common cause with comedians of any stripe as long as they inhabit the art form).

John’s metaphor for the future of the church is a helpful one for me on a personal level; the love I’ve shared with Catherine is, indeed, flexible and strong, quick and enduring. Like tamarack.

Catherine, my partner of nigh on 29 years, has been living with metastatic breast cancer since the fall of 2014 (she would never say “battling” or “suffering from,” and I can attest that she has, indeed, been very much living).

While the last five years have seen many twists and turns, some of them wrenching and painful, like chemotherapy and radiation, and others, like travel, and Oliver’s completing high school, and the simple fact of living to see another year, filled with joy and contentment.

As I write, Catherine is still very much alive. But she’s moved to the PEI Palliative Care Centre, and has stopped being treated for cancer; her life from here will focus on relief of pain, comfort, and quality time with family. In the coming days or weeks she will die.

This is desperately sad, but also not empty of joy and insights and deep, deep emotion of the sort that one seldom gets to experience. We are well-supported by friends and family–the Island blanket is wrapping itself around us, I wrote earlier in the week to a friend–and while we’re not entirely prepared for what the next days and weeks will hold, we know we will weather them together.

Many have written me over recent weeks to ask if there’s anything we need, anything they can do.

We are, I am happy to report, blessed with a well-stocked larder.

But there are things you can do, right now, that will help:

- Go out and buy art and craft made by women. Pay a fair price. Repeat.

- Go and read about Metastatic Breast Cancer. Five years ago I was breast-cancer-illiterate; now I’m not. It helps.

- Learn more about palliative care, and about how “in palliative care” doesn’t mean the same thing as “about to die.”

- If you live on Prince Edward Island, read about the Palliative Home Care Program, which has been a godsend to our family, and is a model for integrated, compassionate healthcare delivery. Mention it to your MLA next time you see them in the grocery line.

- Read How to talk to people about cancer.

- Organize a party for the spring equinox. Set a date. Invite some friends.

- Walk instead of driving.

- Find a young person who wants to learn something, and then learn it with them.

- Accept. And release.

- Make an Advanced Care Plan. Right now, instead of “when I have some spare time.” If not for the utility of the plan itself–which is significant–then for the deep and important conversations it will spur you to have with those you hold dear. Everyone should have one, even if you think yourself immortal.

- Invite a friend out for coffee tomorrow. And invite a stranger out for coffee for the day after tomorrow.

- If you have something you’d like me to tell Catherine, let me know.

Catherine needs all the energy she has, and so isn’t accepting visitors, but I will pass along messages to her.

Thank you to everyone who’s offered a kind word, a coffee date, additional patience, solidarity.

I’m taking a sabbatical from this space for a while, but I shall return.

(Me, Catherine and Oliver, Summer 2019)

When, in early 2013, Catherine suggested that we look into getting an autism assistance dog for Oliver, I thought it was an inane idea: she wanted to take our already chaotic family and inject another complicating element into it?!

But I humored her, and agreed to hear the idea out and meet with a trainer from Dog Guides, the national non-profit organization, funded by Lions Clubs, that runs Canada’s preeminent dog guide program.

That fall we met with Alissa, a trainer, in our living room and she walked us through the program and its aims and objectives, and how they would go about selecting a dog for Oliver should he be deemed eligible. When Alissa left it would be a lie to say that I was 100% sold on the idea, but I deferred to Catherine’s wisdom, for she is far more practiced in the art of such things; I agreed to hold my breath and go all-in should the opportunity arise.

The following spring when we got the go-ahead, and a dog was identified for Oliver, and we were scheduled for 10 days of in-house training at Dog Guides in Oakville I agreed, again with some trepidation, to participate in as much of it as possible. And that March, off we went: as Ethan’s handlers, it was Catherine and I who needed the training; I was there for three days (day one, day two, day three) and Catherine for the entire 10 days.

The way that Dog Guides’ training works is that you don’t actually meet your new dog until day three: they do this so that you pay attention to the material on days one and two, rather than to the new adorable pile of dog that’s just entered your life. It is not an exaggeration to say that all my misgivings instantly melted away when Ethan walked into the room and leapt up on my lap:

That night I wrote:

Today is my last day here in Oakville – I’m back to Burlington tonight to pick up Oliver and head into the city tomorrow for our quick vacation. I didn’t anticipate that I would regret this decision. Not the decision to rejoin Oliver, but the one to leave Ethan. Who ever thought I would actually like him. Miss him, even.

And I did: we had an instant bond, and it’s been a rare day when he hasn’t spent a little time back up on my lap like that, despite his 65 pound weight.

Catherine too formed a bond with Ethan, an even stronger and more powerful one, at least initially, because they spent the following 7 days glued to each other, learning how to be handler-and-handled together:

The way we planned our travels that spring meant that Oliver was around for Ethan’s graduation from training, and so on the final night we were able to go to Dog Guides together for the first time, and Oliver got his chance to meet Ethan:

If it looks like Oliver was smiling in that photo, it’s because he was: he and Ethan took to each other instantly.

A few days later we were all at home, getting used to having a dog living with us and the changes in our daily routine that entailed.

By far and away the most dramatic and immediate positive benefit of having Ethan living with us is that Oliver, who had been waking up with night terrors for the 18 months previous, and often needed Catherine to come and calm him in the middle of the night, started sleeping. Soundly. With Ethan at his side.

While Ethan wasn’t a miracle tonic that brushed the egregious aspects of being autistic away, he was a constant presence in our life, a companion for Oliver, a conversation starter for Oliver (we have all answered the “is he a doodle?” question about 1.2 million times), a bridge to independence for Oliver, a touchstone for Oliver.

Because we were a family that traveled a lot, and because Ethan was allowed to travel with us, no matter by what method, we kept on traveling, with Ethan at Oliver’s side. That first summer we flew to Germany from Halifax, with Ethan under the seat and a bag full of EU dog paperwork:

We rented a VW microbus on arrival and camped our way through the Netherlands and a slice of Belgium, with Ethan and Oliver happily together on the back seat:

The next fall we were back to Europe, with my parents, for a visit to Oslo, and Ethan demonstrated a familial affinity with my mother’s lap:

Later that fall we flew to Montreal to visit my brother and his family, along with my mother; our first flight, from Charlottetown to Halifax, had no “under the seat” for Ethan to fit, so the co-pilot advised to simply give Ethan a seat of his own, so we did:

Also in that fall of 2015, Ethan started to go to school with Oliver every day, something that required an entirely new school board policy to be enacted, and something that spawned a Compass story.

The next spring, Ethan was there with Oliver when he graduated from intermediate school, along with Tom Baker, one of Oliver’s educational assistants who’d been one of Ethan’s handlers at school:

The next fall, when Oliver was off to high school, Ethan was at his side:

And throughout those very difficult first few months in high school, with all its chaos and trauma and anxiety, Ethan was there to offer what comfort he could.

Three years later, when Oliver completed high school as a confident, accomplished, proud 18 year old, Ethan was at his side, along with Dave and Maritza, who played such an important role in Oliver’s (and Ethan’s) passage through Colonel Gray Senior High School:

Along the way Ethan was there when Oliver needed a tooth extracted:

He gamely, if not enthusiastically, participated in several cycling-with-dog experiments, both well-equipped ones in the Netherlands:

And more home-brew efforts here at home:

What we didn’t know when Ethan joined our family in March of 2014 was that six short months later Catherine would be diagnosed with incurable cancer. In one fell swoop everything became more complex, more fraught, more fragile, and Ethan was then, and for five years has continued to be, a stabilizing element, sometimes as much a therapeutic aid to me and Catherine as to Oliver:

After Oliver completed high school last spring, he started at the day program at Stars for Life, and Ethan joined him there too. As the months drew on, Ethan started to exhibit some behaviours that were proving problematic in his service dog role: paying too much attention, too protectively, to other dogs when out and about, for example. This was something that had been developing for a year or two, and something that I’d tried to work on with him, but with a complex family life and a lot going on, I’m afraid I didn’t have the discipline to go at the issue with the rigor it required, and it was becoming more stressful than helpful for Oliver to have Ethan in his day program life.

Simultaneous to this, Oliver himself has been growing more independent: he hasn’t needed Ethan at his side in bed for some years; he’s gained tremendous confidence, and is learning new things and new approaches to solving problems. Ethan’s job as a service dog was becoming less vital in Oliver’s life.

Putting those two together, it was recommended that Ethan retire from daily service in mid-December, and we proceeded with that; as expected, Oliver’s done fine without him, and has, if anything, become more independent as a result.

This left us with the difficult decision as to whether to formally adopt Ethan in his retirement as a family pet, or to ask Dog Guides to find a new adoptive family for him.

This all played out at the same time as Catherine’s cancer was advancing, and the day to day challenges of managing our family were growing; it was a hard time, in other words, to be making big decisions, especially when those big decisions involved the possible voluntary surrender of an important part of our family life.

Ultimately, though, we had to decide what was best for Ethan, and that meant coming to terms with the fact that, despite our best intentions, we don’t have the horsepower to provide him with the love, exercise, and attention he deserves. So we made the difficult decision to send the word to Dog Guides to look for a new home for him; at the same time we sent word out through a network of friends to see if there was anyone locally who might want to take him on.

The holidays interceded in all of this, and we enjoyed Christmas with Ethan and, happily, with Catherine, who left hospital just a few days before Christmas.

With Christmas over, and Catherine, unfortunately, back in hospital, and then, a few days ago, moving to the Palliative Care Centre, I realized that, as much as I could try to keep Ethan in the style to which he was accustomed, it was time to seek assistance more urgently; I contacted Dog Guides and within a couple of hours they identified a local foster family who could take him immediately, and tentative promise of a new permanent adoptive family for him on the horizon.

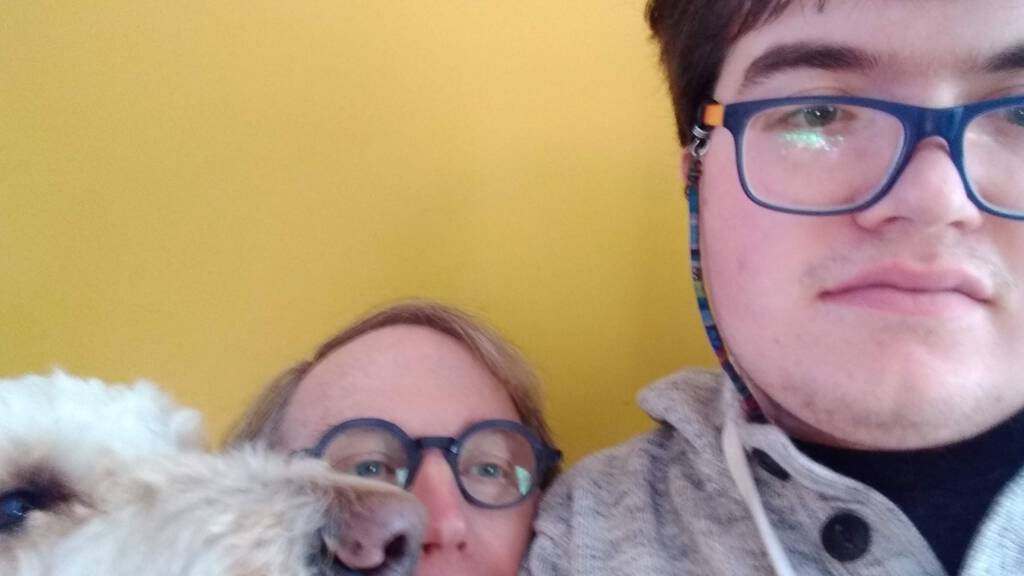

So today, in a way that was really, really hard, we packed up Ethan’s food and his dog bowls and his toys and his biscuits. We took one last selfie:

I let Ethan out in the back yard for one last pee:

And then we three piled into the car for the ride to Ethan’s weigh station on the road to his next chapter. What we found there was a loving home, filled with two other service dogs, one retired and one active, a cat-tolerant dog, and two people who are obviously full of love for animals and will work with Dog Guides to find the perfect new place for Ethan.

It dawned on Oliver, and on me, that with Catherine’s move to Palliative Care, and Ethan moving on, our house at 100 Prince Street is down to just the two of us. We both had tears streaming down our faces for the ride home. It’s a hard day. In a hard week. In a hard year.

When Ethan first joined us, and became a part of our everyday life, in my less-lucid moments I would imagine that eventually someday he would gain the ability to have conversations with me, and I would imagine what we would say to each other.

On this day I simply say thank you, Ethan: you came along at exactly the right time, you helped our family through five wrenching, difficult years, you lightened our load. We are forever in your debt.

Godspeed.

Godspeed is one of my favourite words. I’m going to have to work harder to bring it back into vogue.

See also Ron Hynes.

In recent years the only regular exception I have made to my vegetarianism has been Eugene Sauve’s meat pie at the Landmark Café in Victoria. I even wrote a book about it.

When the Landmark closed, I thought I’d eaten my last meat pie.

But then, a few weeks ago, Eugene sent me a text offering to drop one off.

OMG.

“We’re getting the Beatles back together.”

We enjoyed it for supper tonight. And it was as good as it ever was.

I am

I am