To the anonymous person who, perhaps knowing what a trying week this has been for our family, left a bag of potato chips with french onion dip in our front vestibule today: you are the greatest—the greatest.

My friend Chantal, a fellow fountain pen aficionado who I met through Pen Night, is a talented artist and illustrator; after seeing my letterpress in action in July, she set out to see if she could take her pen and ink artwork and have it turned into a custom die, suitable for use in letterpress printing.

Today was the day to take her experiment out for a ride on the press; while I will leave it to her to reveal the result of the main event, she surprised me with the lovely gift of an additional die that she designed and had made, an image that, I think you’ll agree, lovingly captures the spirit of me and my printery:

Of course I had no choice but to print a whole big bunch of them, on Artists’s Tile Set acid-free cards from Peter Pauper Press in New York:

The unexpected gift, from the hand and the heart, is the best gift of all. Thank you, Chantal.

You watch one Alexa Chung video on YouTube and then YouTube is, like, “how about another Alexa Chung video!” And suddenly all you’re watching is Alexa Chung videos. Like The Making of the Met Gala 2019 Dress.

I’ve learned more about fashion in the last 48 hours than I thought there was to learn. Chung is a good teacher: a potent mix of humility, moxie, design sense and iconoclasm.

Beware “vanilla scented” draft-stopping caulking compound. Unless you like your vanilla scent to smell like an amalgam of nuclear waste and turpentine.

This is the January 1, 2020 schedule.

Maybe you’re looking for the 2023 Levee Schedule?

This is the 2020 levee schedule for New Year’s Day, January 1, 2020 for Charlottetown and Prince Edward Island.

Show levees that are ages 19+ Show only Charlottetown-area levees

| Organization | Location | Starts | Ends | ♿ Accessible | All Ages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timothy’s World Coffee | Timothy’s World Coffee 154 Great George Street, Charlottetown, PE |

8:00 AM | 10:00 AM | Yes | Yes |

| The Guild | The Guild 111 Queen Street, Charlottetown, PE |

9:00 AM | 10:30 AM | Yes | Yes |

| Upstreet Craft Brewing | Upstreet Craft Brewing 41 Allen St, Charlottetown, PE |

10:00 AM | 11:00 AM | Yes | Yes |

| Lieutenant Governor | Government House 1 Terry Fox Drive, Charlottetown, PE |

10:00 AM | 11:30 AM | Yes | Yes |

| Mayor of Charlottetown | Charlottetown City Hall 199 Queen St, Charlottetown, PE |

10:30 AM | 12:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| CrossFit 782 | Crossfit 782 570 North River Rd, Charlottetown, PE |

11:00 AM | 1:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| HMCS Queen Charlotte | HMCS Queen Charlotte 210 Water Street, Charlottetown, PE |

11:00 AM | 1:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| The Haviland Club | The Haviland Club 2 Haviland St, Charlottetown, PE |

11:00 AM | 4:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Copper Bottom Brewing | Copper Bottom Brewing 567 Main Street, Montague, PE |

11:00 AM | 6:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Silver Fox Curling and Yacht Club | Silver Fox Curling and Yacht Club 110 Water Street, Summerside, PE |

11:00 AM | 6:00 PM | Yes | No |

| University of PEI | School of Sustainable Design Engineering 550 University Ave., Charlottetown, PE |

11:30 AM | 1:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Prince Edward Island Regiment | Queen Charlotte Armoury 3 Haviland Street, Charlottetown, PE |

12:00 PM | 1:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Mayor of Kensington | Family and Friends Restaurant 45 Broadway St N, Kensington, PE |

12:00 PM | 1:30 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Town of Stratford | Stratford Town Centre 234 Shakespeare Dr., Stratford, PE |

12:00 PM | 1:30 PM | Yes | Yes |

| PEI Brewing Company | PEI Brewing Company 96 Kensington Road, Charlottetown, PE |

12:00 PM | 2:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Royal Canadian Legion - O’Leary | O’Leary Legion 69 Ellis Ave., O’Leary, PE |

12:00 PM | 7:00 PM | No | No |

| Seniors Active Living Centre | Bell Aliant Centre 550 University Avenue, Charlottetown, PE |

12:30 PM | 2:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Andrews of Stratford | Andrews of Stratford 355 Shakespeare Drive, Stratford, PE |

1:00 PM | 2:20 PM | Yes | Yes |

| St. John’s Lodge No. 1 and Victoria Lodge No. 2 | Masonic Temple 204 Hillsborough St., Charlottetown, PE |

1:00 PM | 2:30 PM | No | Yes |

| Town of Souris | Eastern Kings Sportsplex 203 Main Street, Souris, PE |

1:00 PM | 3:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Town of Three Rivers | Kaylee Hall 2316 Rte 3, Roseneath, PE |

1:00 PM | 3:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Village of Morell, Morell Lions Club, Northside Communities Initiative | Morell Community Rink 59 Queen Elizabeth, Morell, PE |

1:00 PM | 3:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Town of O’Leary | Maple Leaf Curling Club 426 Main Street, O’Leary, PE |

1:00 PM | 4:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Royal Canadian Legion - Tignish & Town of Tignish | Tignish Legion 221 Phillip Street, Tignish, PE |

1:00 PM | 5:00 PM | Yes | No |

| Royal Canadian Legion - Wellington | Wellington Legion 97 Sunset Dr, Wellington, PE |

1:00 PM | 5:00 PM | Yes | No |

| Roman Catholic Diocese of Charlottetown | SDU Place – Old Bishop’s Palace 45 Great George Street, Charlottetown, PE |

1:30 PM | 2:30 PM | Yes | Yes |

| City of Summerside | City Hall 275 Fitzroy Street, Summerside, PE |

1:30 PM | 3:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Town of Cornwall | Cornwall Town Hall 39 Lowther Drive, Cornwall, PE |

1:30 PM | 3:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Royal Canadian Legion - Summerside | Summerside Legion 340 Notre Dame St., Summerside, PE |

1:30 PM | 5:00 PM | Yes | No |

| Garden Nursing Home | Garden Home 310 North River Road, Charlottetown, PE |

2:00 PM | 3:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Royal Canadian Legion - Charlottetown | Charlottetown Legion 99 Pownal Street, Charlottetown, PE |

2:00 PM | 3:30 PM | Yes | No |

| PEI Billiard Association | Dooly’s 157 Kent St., Charlottetown, PE |

2:00 PM | 4:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Town of Borden-Carleton | Town Office 20 Dickie Rd., Borden-Carleton |

2:00 PM | 4:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Royal Canadian Legion - Miscouche | Miscouche Legion 94 Main Drive, Miscouche, PE |

2:00 PM | 6:00 PM | Yes | No |

| The Kitchen Witch | The Kitchen Witch 949 Long River Road, Long River, PE |

2:30 PM | 4:30 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Premier Dennis King | Confederation Centre of the Arts 145 Richmond St, Charlottetown, PE |

3:00 PM | 4:30 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Benevolent Irish Society | Hon. Edward Whelan Irish Cultural Centre 582 North River Road, Charlottetown, PE |

3:00 PM | 5:00 PM | Yes | Yes |

| Royal Canadian Legion - Ellerslie | Ellerslie Legion 1136 Ellerslie Road, Ellerslie, PE |

3:00 PM | 7:00 PM | Yes | No |

| Charlottetown Curling Club | Charlottetown Curling Complex 241 Euston St, Charlottetown, PE |

4:00 PM | 6:00 PM | No | No |

| Murphy’s Community Centre & The Alley | Murphy’s Community Centre 200 Richmond Street, Charlottetown, PE |

4:00 PM | 6:00 PM | Yes | No |

| Sport Page Club | Sport Page Club 236 Kent St, Charlottetown, PE |

4:00 PM | 6:00 PM | No | No |

| Olde Dublin Pub | Olde Dublin Pub 131 Sydney St., Charlottetown, PE |

5:00 PM | 8:00 PM | No | Yes |

| 200 Wing Royal Canadian Air Force Association | The Wing 329 North Market Street, Summerside, PE |

6:00 PM | 10:00 PM | Yes | No |

| Charlottetown Firefighters Club | Charlottetown Fire Department 89 Kent Street, Charlottetown, PE |

6:00 PM | 12:00 AM | Yes | No |

The levee schedule is covered under a Creative Commons Attribution, NonCommercial, ShareAlike License.

The University of Prince Edward Island publishes reports of employee travel expenses every month. Unfortunately these reports are published as PDF files, making any sort of data analysis unreasonable.

Because I am interested in learning more about university travel, primarily with an eye to understanding–and working to mitigate–its carbon footprint, it’s data analysis I want to do.

So, on November 11, 2019, I submitted an access request for the raw machine-readable data lurking underneath these PDF files:

There are PDF files, released under proactive disclosure, of UPEI employee travel expenses that are not machine-readable. I request machine-readable data, in CSV format, for employee travel expenses for the period January 1, 2016 until the most recent month available at the time of this request. I further request that this data format be added to the proactive disclosure page.

Thirty days later, on December 10, 2019, I received the data I requested, albeit only for the period from April 2019 to October 2019, along with an explanatory letter.

The shorter time-frame was explained to me like this:

Unfortunately, access to some of the information that you requested is outside of the scope of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. Section 4(1.1) makes the Act effective for UPEI from April 1, 2019 going forward. Records created prior to April 1, 2019 will not be released through a request made under the Act.

There are processes for accessing certain information created before April 1, 2019. However, there is no process available for requesting information which has already been made publicly available on the UPEI website.

My mother, who worked as a law librarian, once explained the difference between the “letter of the law” and the “spirit of the law,” and this response clearly falls into the “letter of the law” bucket.

Regardless, I now had some data to analyze.

One of the things you learn as a frequent access-requester is that you can learn a lot about data management systems from the quality of the data you receive: in the case of UPEI travel expenses data, there are myriad inconsistencies that suggest, taken together, that this data is gathered with little concern for quality control nor anticipating aggregate analysis:

- Names are inconsistent, both in spelling and in form (sometimes “Doug” and sometimes “Douglas,” for example).

- Department names are inconsistent (sometimes “Procurement” and sometimes “Procurement Services,” for example).

- Departments within the Atlantic Veterinary College, like “Health Management,” are listed separately, without an explicit connection to the AVC.

I had to do a lot of manual editing of the data to get it normalized to the point where I could do accurate analysis.

Here’s what I found.

Expenses by Person, April to October 2019

After normalizing the data, I loaded the edited CSV file into LibreOffice and created a pivot table by name, summarizing the total of the “transportation” and “accommodations” columns into a single “total travel expenses” column. I then sorted this result in descending order of expenses, converted to an HTML table, and then used DataTables to render the result (you can search–by person or department–sort, and page through the data).

One thing to note: whereas all other employee travel was conducted in 2019, Louis Doiron’s travel expenses claims included travel going as far back as 2016, which contributes to his higher total.

Expenses by Department, April to October 2019

This is a similar pivot table, but by department. Again, you can search (for a department name), sort and page through the data.

Calculating Carbon Footprint

Because of the varied formats that travel destinations are provided in the travel expenses data files, it’s a challenge automatically calculate carbon footprint–destinations include, for example “East, West and Central, PE” and “Portland, ME, Linthicum, MD and New York, NY, US” and “Various Northeastern States, US.”

It’s possible to make some manual calculations, however.

For example, Jackie Podger, Vice-President Administration and Finance, submitted claims for 6 trips:

- March 28-29, meeting in Halifax, NS

- May 22-23, meeting in Toronto, ON

- June 9-11, conference in Halifax, NS

- July 7-13, conference in London, UK

- August 21-22, meeting in Toronto, ON

- October 4-9, meeting in Cairo, Egypt

Assuming driving to Halifax and flying everywhere else, the carbon footprint, in CO2E from flying (calculated by Atmosfair, assuming economy travel on scheduled flights) is:

- Charlottetown to London, via Montreal: 2.8 tonnes

- Charlottetown to Toronto: 0.80 tonnes

- Charlottetown to Toronto: 0.80 tonnes

- Charlottetown to Cairo, via Montreal: 5.2 tonnes

For a total footprint of 9.6 tonnes.

Adam Fenech, Director of the Climate Lab, submitted claims for 5 trips:

- January 4-10, meeting in Dubai, UAE

- February 2-6, conference in Toronto, ON

- April 21-28, conference in Amsterdam, NL and Ghent, BE

- October 19-30, conference in Beijing, China

- September 15 to October 13, meetings on PEI

Leaving out the on-Island travel, a guess at the carbon footprint breakdown from flying, again calculated by Atmosfair:

- Charlottetown to Dubai, via Montreal: 6.6 tonnes

- Charlottetown to Toronto: 0.80 tonnes

- Charlottetown to Amsterdam, via Montreal: 3.1 tonnes

- Charlottetown to Beijing, via Montreal: 6.4 tonnes

For a total footprint of 16.9 tonnes.

(Atmosfair’s figure for the “climate compatible annual emissions budget for one person” is 2.3 tonnes).

Is university travel sustainable?

Travel is, at present, a necessary aspect of academic and administrative life: face-to-face meetings and conferences are central to the way the academy works, part of its operating system.

It’s clear that this isn’t sustainable, and that we’re going to need to find alternatives.

The University of PEI doesn’t publish data on the carbon footprint of employee travel, but it should: while at some point soon it might be feasible, and important, to place limits on employee travel, requiring the carbon footprint of all travel to be recorded and published would be a positive, easily-implemented first step.

The public scrutiny of this information, combined with the self-reflection it would engender, would, I believe, result in reduction in travel, travel in a more efficient manner, and would stimulate research into workable alternatives to frequent travel that could keep the wheels of the academy turning.

The Data

If you’re interested in exploring the raw data yourself, I’ve published it to a GitHub repository.

(“Where is Matthew going, and why is he going there?” is a line from the song Where is Matthew going? from Anne of Green Gables–The Musical, lyrics by Don Harron and Norman Campbell.)

The first public high-speed electric vehicle charger in Charlottetown is on the brink of opening. You’ll find it in the corner of the Canadian Tire parking lot.

While it can take up to 24 hours to charge our Kia Soul EV from a standard outlet, 5 hours from the level 2 charger pending installation off our driveway, this new DC charger should get the Soul to 80% charged in about 30 minutes.

Fast charging like this is the infrastructure that enables longer-distance EV trips, and the network of 6 DC chargers that Efficiency PEI is about to launch will be a welcome addition for EV owners looking to visit friends east and west.

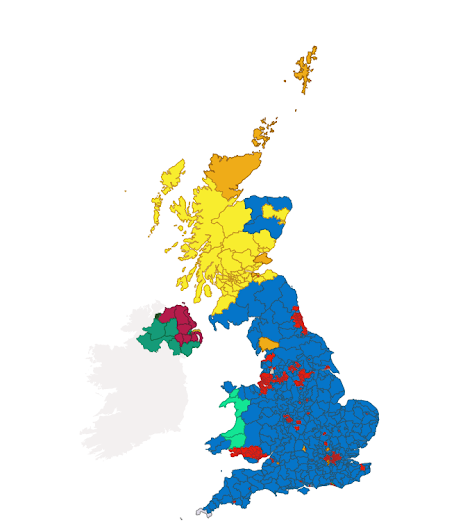

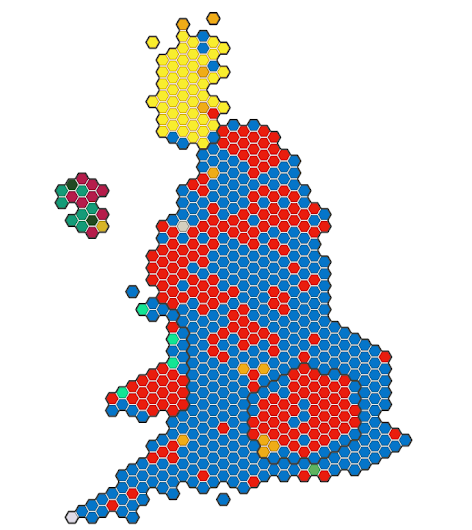

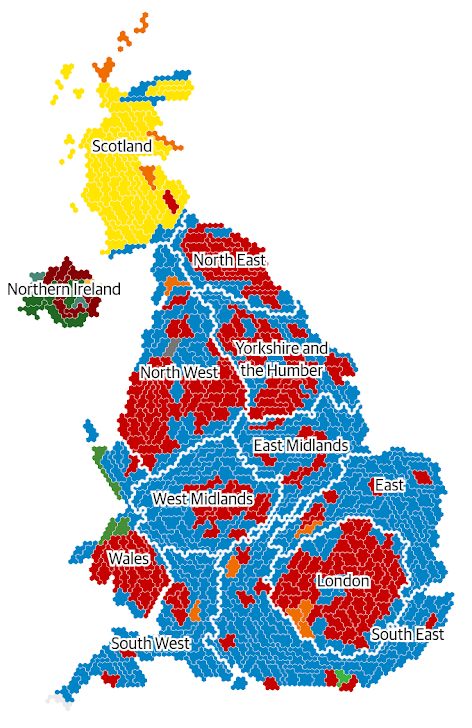

The BBC News website presented two different visualizations of yesterday’s UK elections.

The first is strictly geographical, with the land area of each constituency accurately represented on the map:

By flipping a switched at the bottom of the map you can see the same results rendered as a “cartogram,” which presents each constituency as the same geographic size, located in roughly the relative area of the country, but not geographically accurate:

The Guardian presented a similar treatment, with each constituency the same size, but presented in a more malleable, and thus more familiar form:

Because of differences in population density, the two approaches tell very different stories.

The Electoral Cartogram of Canada website presents a similar treatment for the 2019 Federal Election here in Canada; in this case, because of higher MP-to-population ratio in places like PEI, the Island has an outsized appearance.

Laurie Brown interviews Leif Vollebekk for Pondercast.

Like she says, “There is nothing better than discovering a new artist you love.”

St. Paul’s Anglican Church has created a new position of Parish Activity Coordinator; Archdeacon John Clarke described the genesis of this position in this blog post, and you can read the full job description here.

As a happy and content secular tenant of the parish, I can attest that this is a welcoming, caring community; for the right person, taking on this position could not only represent a satisfying job, but also an opportunity to profit from the personal and spiritual growth that being in a community of dedicated parishioners in a progressive church can bring.

I am

I am