I have a general policy of donating to any project that Gary Schneider, coordinator of the Macphail Woods Ecological Forestry Project, is behind; the latest is the Restore An Acre initiative. It’s a sensible project, that connects a donation of $200 with the restoration of an acre of the Selkirk Road Public Forest. I’ve just made a donation; I’d ask you to do the same.

Restore an Acre from Macphail Woods on Vimeo.

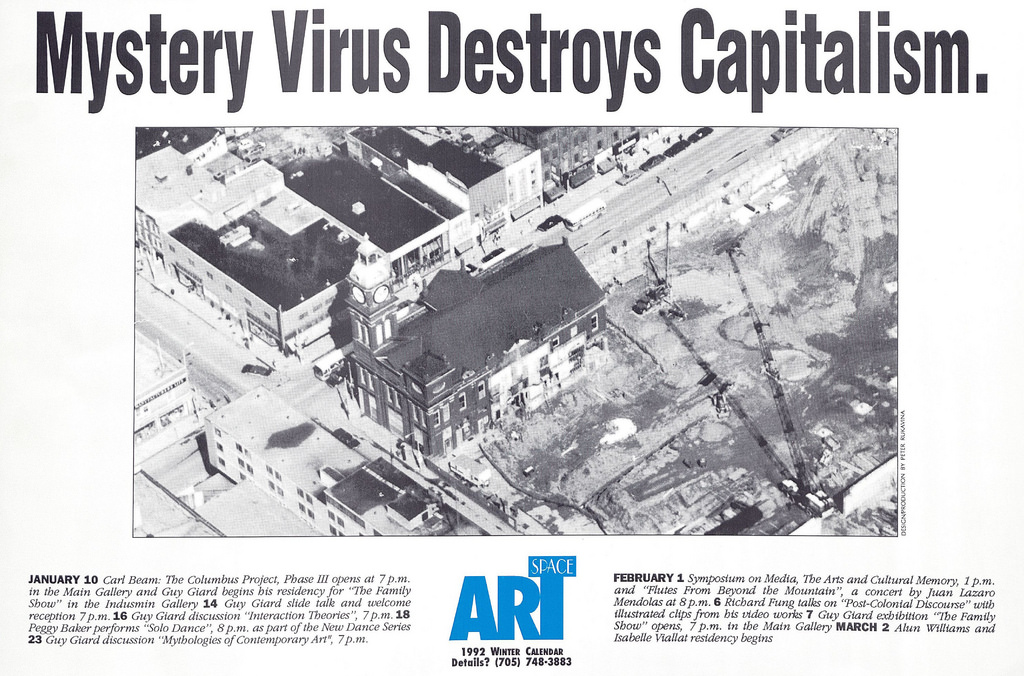

In the fall of 1992 I was living in Peterborough, Ontario doing freelance design work after almost 2 years spent in the composing room of the Peterborough Examiner newspaper. Catherine and I were living in a spacious apartment on Hunter Street. A few months later we’d leave Peterborough and relocate to Prince Edward Island, so what ended-up being my last design job was to design a season poster for Artspace, the artist-run centre that, at the time, was based in the Market Hall downtown.

It was a happy accident that I got the job: Artspace was in transition that year and, if memory serves, had no staff for a time. So I could get away with a lot, and had no “branding guidelines” to stick to. Nor, indeed, any oversight at all, excepting the very flexible, accepting imagination of board member Lynn Cummings, whose responsibility it was to have a season poster designed.

By lucky happenstance, I happened to be browsing a book in the Peterborough Public Library that week about the history of the city, and I came across a photo of the central block around the Market Hall being redeveloped into Peterborough Square, one of the many downtown-redevelopment projects that afflicted (or saved, depending on your point of view) urban cores in small-town Ontario in the 1970s. All of the buildings on the block, save the Market Hall, which was to remain, had been torn down. The site was empty. The block, for some rare months, was free of any business activity.

And thus was born “Mystery Virus Destroy Capitalism.”

I figured if I was being irreverent, I might as well go all the way, so I took the opportunity to design a new logo for Artspace while I was at it. The new logo didn’t take – as far as I know, this was the first and only time it every appeared in print.

The poster was printed on glossy 11” x 17” card stock and distributed liberally about the city.

It was the most fun I ever had doing graphic design, and the only time I think I ever managed to capture a small slice of the zeitgeist in my work.

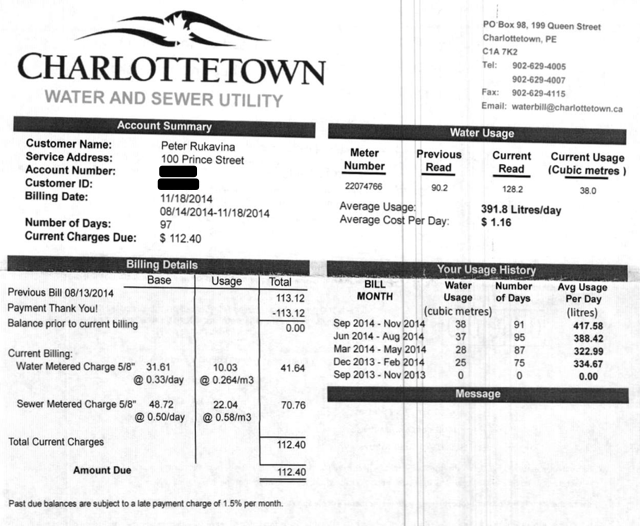

We’ve now had a water meter in our house at 100 Prince Street for almost a year, so it’s a good time to look at what it’s costing us for water with a meter vs. what it was costing us under the old “all you can eat” plan.

Our 2013 annual bill was $510.88, payable in four installments of $127.72.

We’ve received three bills under the new metered regime that reflect full quarters: May’s bill was $99.08, August’s bill was $113.12 and November’s bill was $112.40, for an average of $108.20, or about 15% less than what we were paying before.

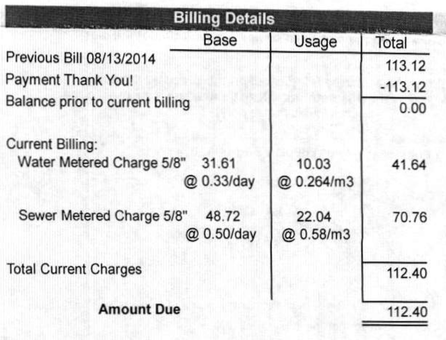

Charlottetown Sewer and Water redesigned it’s bills this fall, and the new bills provide much more detail about usage and billing. Here’s a snippet from our November bill:

A couple of things jump out on that bill.

First – and this is something that was never broken out before in the old bills – is that we are billed for both water coming in (“water”) and water going out (“sewer”) and we pay more than twice as much per cubic meter for sewer than we do for water. This used to be ganged together under “water and sewer” on the bill, and it’s nice to see it broken out as it reinforces the fact that water used is water that needs to be disposed of, and that costs a lot of money.

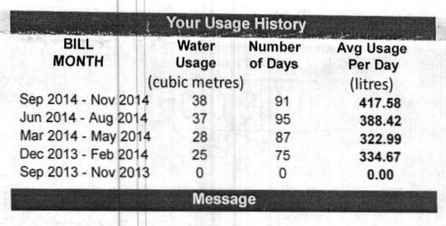

Second is that the “base” rate, which isn’t affected by consumption, is a significant part of the bill – about 70%. That means that even if we used no water at all we’d still pay $80.33 a quarter just to be connected to water and sewer. I don’t begrudge that, as there’s obviously a liability to the utility as I could use water at any time. But it does dampen the incentive to conserve, and it dulls the financial feedback one gets from conserving or consuming more. For example, here’s our consumption history for the past five quarters:

Our consumption from last quarter increased 7%, and yet our daily cost for water went from $1.19/day to $1.23/day, an increase of only 3%; the fixed base charge made the perceived cost of our increase in consumption less than half as “impactful” as it would have been without the base charge.

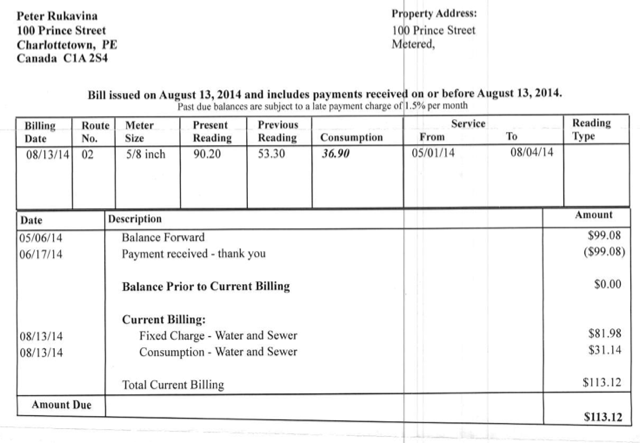

All that said, the new water bill is a huge improvement over the old design: here’s a comparison of old vs. new.

Here’s our bill, in the old format, for August 2014:

And here’s our bill, in the new format, for November:

The new format is clearer, exposes considerably more detail, and provides consumption history information that was never aggregated together before.

It’s been a stormy day here in Prince Edward Island, most especially on the western end. We had a PEI Home and School Federation board meeting scheduled for this evening, but the bad weather put having a quorum at risk.

So we looked to Skype to pull the meeting off.

We tried this on a smaller scale last year for a subcommittee meeting, and it worked relatively well, and since that time Skype has made “Group Video Chat” free for all users (it was a paid subscription service until recently), so it seemed like a viable option. But we’d also tried to Skype a single director into a meeting earlier this year, and he got lost in the shuffle, so I was cautious.

In the end we had 12 of our directors who could make the meeting: 4 attended in person, in the board room at Casa Mia Café (generously donated to the cause at the last minute) and 8 people attended via Skype.

Of those eight, we called one person on the phone (with Skype), and one person was on an iPad, which only supports audio for group chat, so we had 6 people with video and audio, and 2 people with only audio.

The Casa Mia board room has a large 1080p Sony television mounted on the wall at one end of a board table; here’s what it looked like when I was testing the setup with [[Catherine]] and [[Oliver]] via Skype:

I used my MacBook Air, plugged into the TV via a VGA connector, to display Skype, and used the MacBook’s internal microphone to pick up sound in the room (arguably the weak link in the system, as it was sometimes difficult for Skypers to here people in the room).

And it worked!

We held the meeting, which took about 90 minutes, and every one stuck in and it went, for most intents and purposes, like a regular board meeting.

Some lessons learned:

- Leaving time for “rehearsal” before the meeting started was a good idea. 15 minutes before we were scheduled to start I called each Skype participant to verify that their setup was working, that we could see and hear each other. Now that those 8 people have done it once, we’re better prepared for the next time.

- It really helps to be “Skype contacts” with everyone that’s going to be participating by Skype before the meeting starts because Skype appears to require that you’re a contact before you can be added to a

Group Video Chat.” This was a stumbling block getting started for a couple of people I’d sent contact requests to who hadn’t acknowledged them: I had to re-send the contact request to get things rolling. - Skype isn’t as good as Google Hangouts and GoToMeeting at showing the person who’s talking in a larger video window: this “highlighted person” in Skype seemed to be selected at random and/or perhaps affected by the background noise in the remote locations. This wasn’t a big deal, but if it had worked better we sometimes would have been clearer who was speaking at any given point.

- If someone on Skype starts speaking, it’s hard for them to hear anyone else speaking, which makes “are there any other questions about this” style requests for comment a little more difficult to handle because people end up talking over each other.

- The single best thing we did was to make sure that everyone in the room talked toward the MacBook, and spoke loudly and clearly.

- I was chairing the meeting, and stopped twice just to check in and make sure that everyone on Skype could still see us and hear us and to take a “roll call” of sorts to make sure nobody had dropped out.

- Having the large TV was a big help: if everyone in the room had to gather around a tiny laptop screen it wouldn’t have worked.

By holding the meeting via Skype we were able to avoid 3 people driving from Summerside, one person driving from Souris, one person driving from Crapaud and one person driving from up west, so in addition to making the meeting possible, we also saved a lot of driving and a lot of people’s time.

It all worked well enough that we might consider making the option a regular part of our board meeting routine.

Couples never kiss in Aaron Sorkin television dramas.

They argue.

They argue epically, eloquently, passionately.

In Aaron Sorkin’s made-up world, argument is the currency of love.

Lt. Daniel Kaffee argues with Lt. Cdr. JoAnne Galloway. President Andrew Shepherd argues with Sydney Ellen Wade. CJ Cregg argues with Danny Concannon. Danny Tripp argues with Jordan McDeere. Will McAvoy argues with MacKenzie McHale.

And, in this week’s episode of Sorkin’s The Newroom, Jim Harper (John Gallagher, Jr.) argues with Hallie Shea (Grace Gummer). The entire scene runs just over four minutes; here’s the last 38 seconds:

Surely this must rank as one of the most compelling couple-arguments in modern television.

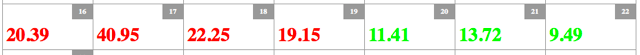

As part of my Social Consumption Project, I’ve had an electricity meter reader logging our household usage to a database since late September.

The week of October 5 our house was empty – I was in the west coast and Catherine and Oliver were in Ontario – and so this gave us a great chance to find out what the base electric load of our house is when there’s nobody living in it. Here’s what we found (number are kWh per day from October 5 to October 11, 2014):

Other than lights, we took no steps to turn things off during our absence – poor planning – and so the bulk of the consumption that week were things like the refrigerator, the “instant-on” appliances, like our TV set, and our iMac computer, which we left on (and which was used a couple of times a day by our friend G. who was checking the house for us).

Maritime Electric’s charge for electricity is 12.78 cents per kWh, so our electricity was costing us between 64 cents and and 77 cents a day. So we weren’t going broke. But that’s that’s still $5.00 that we didn’t, in theory, need to spend that week.

By comparison, here’s our electricity usage for this week, when the house was fully occupied:

We used 117 kWh this week, which is 79 kWh more than an empty house, which you could say is our “discretionary” electricity – the stuff we do deliberately by turning something on.

Which made me curious: that 38 kWh our house used the week we were away, the electricity the house uses when we don’t deliberately turn something on, what’s using that?

And so I borrowed an electronic energy meter from the Confederation Centre Public Library (almost every public library on Prince Edward Island has one, so this is easy for anyone to do, and it’s free) and this weekend Oliver and I measured the electricity consumption of everything in the house that plugs in. Here’s a chart showing the “stuff that’s always on that uses electricity”:

| Appliance | Load |

|---|---|

| Refrigerator | 30 watts |

| Mouse Repeller | 3 watts |

| Television | 4 watts |

| Nintendo Wii | 8 watts |

| Stereo | 11 watts |

| Eastlink Router | 9 watts |

| Apple Airport Extreme | 7 watts |

| VOIP Telephone Box | 5 watts |

| iMac Computer | 94 watts |

| TOTAL | 171 watts |

There are some other things that aren’t counted in that total – the furnace coming on, a light that’s always on in the upstairs bathroom – but that total covers almost everything.

And so our “idle” household uses almost as much electricity as a 200 watt light bulb left on all the time.

And, indeed, 171 watts per hour is 0.171 kWh and 0.171 kWh for 24 hours is 4.1 kWh, which is within 1 kWh to what my electricity meter readings showed (the difference was likely those things we didn’t count, plus some lights that G. would have used).

There are some things we can do to lower this base load, some of which I’ve already done:

- I’ve moved the television, stereo and Wii to a power bar that I can shut completely off when we’re not using them: that will save us 23 watts of load, or about half a kWh per day if we never turned them on.

- We could have the iMac go to sleep (rather than just “idling” with the display off); this could save about 2.25 kWh per day if we never turned the iMac on.

Of course if nobody at all was going to be using the house, we could also turn off the Internet gear and the phone and we’d save even more.

The other step we’ve taken is to start to replace incandescent and compact florescent light bulbs with LED bulbs, starting in the living room. So far I’ve replace 221 watts of load with 59 watts but replacing the bulbs in the three lamps we use most often.

It may seem absurd to be taking these seemingly minor steps that will save us a few dollars a month on our electricity bill at most. But these small things mean a lot on a province-wide level.

There are about 40,000 households in Prince Edward Island. If each of those households has a computer on all the time that consumes about 100 watts of electricity, that’s 4 millions watts of electricity being used to power all those computers; that’s 4 megawatts, or about 2% of the Island’s electricity load (193 MW) as I type this sentence. That’s a lot of electricity, and it’s electricity that we weren’t using a generation or two ago. It’s also electricity that we could save a lot of if we put our computers to sleep (or turned them off) when we’re not using them.

I just absolutely love this duet, shot cliff-side near Cannon Beach, Oregon and featuring couple-in-banjo-and-life Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn. For more on the Washburn-Fleck union, watch this PBS NewsHour story.

We generally keep [[Ethan]]’s hair clipped short: he’s a working dog, not an ornamental poodle, after all.

But we’ve been busy over the last month, and let his hair get a little on the long side, to the point where it was looking like he might have difficulty seeing through the shag soon.

So we made an appointment at Petsmart for this morning and dropped him off looking like this:

When we picked him up four hours later, he look like this:

It’s hard to believe that’s the same dog.

It will grow back soon.

Two years ago next week I found myself trying to get to sleep in a Halifax hotel and so, as I often do, I listened to a podcast, the episode of Alec Baldwin’s Here’s the Thing where he interviewed Dr. Robert Lustig about the evils of sugar.

Toward the end of that interview Baldwin asked Lustig what public policy changes he recommended to lower sugar consumption; Lustig responded, in part (emphasis mine):

I would think very strongly about limiting access of sugar beverages to infants and children, like zero. There is no reason for it. And there’s something your listeners need to understand: there is not one biochemical reaction in your body, not one, that requires dietary fructose, not one that requires sugar. Dietary sugar is completely irrelevant to life. People say oh, you need sugar to live. Garbage.

(Here’s the audio of the clip).

For some reason, on that sleepless cold Halifax night in a strange hotel that simple statement hit me over the head like a hammer.

It seems silly to say, but it had never occurred to me that we don’t actually need sugar.

Sure, I knew that it was a good idea, for a host of reasons, to not have “too much” sugar – what kid who grew up in the carob-infused 1970s didn’t know that – but the notion that there wasn’t actually a need to have any sugar at all was something I’d never considered.

Over the years I’d had friends who would tell me “oh, I cut out sugar,” and I always heard that in the same spirit one might hear “oh, I cut out breathing”: it seemed like a foolhardy, impossible task.

But there, then, that night I decided to give it a try.

Partly as a personal challenge (it did indeed seem like a foolhardy, impossible task).

Partly as a way of figuring out how much sugar I actually was consuming.

And partly because, if Dr. Lustig was to be believed, I had a decent chance of improving my health if I did.

And so, when we got home to the Island a few days later, I just stopped.

It wasn’t a full-on puritanical “no sugar will ever touch these lips” kind of cold turkey, but it was as close as I could practically come while still allowing for the occasional piece of birthday cake.

And what did I find? I was eating a lot of sugar.

For example, a couple of times a week I’d have lunch at Tai Chi Gardens, a tea house around the corner from my office. In the summertime I’d always order a lemon iced tea with my lunch, reasoning that it was “handmade” by people I knew and therefore must be much better for me than if, say, I’d had a Coca-Cola at Subway.

But then I watched how much sugar goes into a lemon iced tea and I realized that sugar is sugar is sugar, and I started to order my lemon iced tea without sugar.

Among other things, I also stopped eating: ice cream, chocolate bars, dessert after lunch and supper, sugar in my coffee, sweets at bake sales, a cookie here or there, a handful of chocolate chips when they presented themselves; essentially I stopped eating all the “discretionary” sugar I’d been eating before, without obsessing about the hidden sugars in many prepared foods.

The effect was immediate and dramatic: I began to crave bread like never before. And when I say “crave” I mean “involuntarily bake bread at 10 o’clock at night because I really, really need to eat some bread.”

That lasted about a week.

And then… I lost my taste for sugar. Indeed the occasional lapse – a Mars bar at the movies, a piece of birthday cake at a family party – would not only no longer make me feel “better” as it used to but, in fact, would have the reverse effect, making me feel nervous and uncomfortable. It was a tremendous and convenient disincentive to sugar-eating.

And now two years have passed.

There’s no doubt that I confronted the amount of sugar in my diet, and came away surprised at how much I’d been consuming.

Health-wise, I have only a vague largely anecdotal feeling that my health has improved. Certainly I’ve lost some weight – about 20 pounds over two years. And I feel like my immune system is considerably improved (those winter colds that last days for others seem to pass through me in a few hours). But I’ve no idea whether I can chalk any of that up to sugar or not.

I still eat sugar, of course: it’s hard not to when it’s found in all manner of things including in salt (yes, one of the ingredients on our box of salt is “sugar,” albeit trace amounts). And I have a banana muffin most mornings for breakfast which I know contains more sugar than I can probably imagine (breakfast is a challenge for a non-egg-eating mostly-vegetarian). But I’d hazard a guess that I’ve been able to cut out about 95% the low-hanging obvious sugar in my diet.

Otherwise, I’ve been able to make some observations from this new vantage point.

The “sugar industrial complex” is everywhere and no more so than on television; by happy coincidence we cut off our cable television a few months before I cut off sugar, and with it I lost most exposure to Dairy Queen Peanut Buster Parfait commercials, Mr. Big chocolate bar commercials, Coca-Cola commercials, and the like. I’m certain that made early days easier.

There may be no nutritional need for dietary sugar, but that doesn’t mean there’s not a cultural need for it: there are holes in our day to day western life that we fill, generally, with sugary things. Coffee breaks. The time after supper. Birthday parties. Christmas parties. Hallowe’en. It’s not that these times are practically difficult to deal with – I’m not jonesing for sugar – but I do notice the holes nonetheless, and, in a strange way, I mourn the loss of my participation in them. The display case at my coffee shop is filled with intriguing-looking scratch-made desserts, and bypassing them and just ordering coffee leaves me feeling the same way that former smokers have described feeling when they go to bars after the quit… they miss having something to do with their hands, something to fill the time with. It’s weird.

It’s not powerful – more like background radiation – but it’s weird nonetheless.

All other things aside, perhaps the greatest lesson I take from this experiment-turned-lifestyle is that, when in the right frame of mind, I am capable of making substantial lifestyle changes. That’s a good thing to know, and makes we wonder what other things I could accomplish if I found the rationale and put my mind to it.

In the spring of 2005 we spent a month in the small village of Aniane in the south of France. The trip was the first test of my “I can work from anywhere” hypothesis, and the results of the experiment showed that this was just barely true: the house we rented was free of Internet, leaving me to scavenge for wifi in the surrounding towns, and the ergonomics of the attic I set aside to be my office were such that rope and pillows were required to strap me into a comfortable work position.

But, work logistics aside, it was one of the greatest trips we’ve taken as a family: Aniane was a tiny, perfect village with two boulangeries, a mid-week market and awe-inspiring stone architecture, surrounded by enough distractions to keep us pleasantly occupied for the month with fun family activities. Sometimes it was enough just to wander about the village, taking it all in.

The nearest major city, 30 minutes drive away, was Montpellier, and we would often go into the city to shop, or to wander, or to ride its city-centre carousel. A few minutes walk from the carousel was a park called L’Esplanade, and one of the features of L’Esplanade was that it offered pony rides for children.

Which is how we met Bembo.

Bembo was one of the stable of ponies, and was the one selected for Oliver to go on walkabout around the park. We paid our fee – a Euro, if I recall correctly – and were surprised to find that our marching orders were to simply set off, under Bembo’s guidance, through the park. In stumbly French I managed to determine that Bembo knew the way; there was nothing to worry about.

And Bembo did know the way: he dutifully, calmly, loped on his standard route, around and about and through, never diverging from his intended course. If we’d fashioned ourselves as pony thieves it never would have worked out, as Bembo’s determination to stay the course was unbreakable: he wouldn’t divert no matter how hard we might have pulled.

Everything went sideways, however, when we came to a section of the brick path that workers had just started to dig up: what was Bembo to do?

He couldn’t go forward, he couldn’t go backward, he wouldn’t go around.

So he stood there. Waiting.

It took all our strength and persuasive energies to convince Bembo that it was okay to divert 6 inches to the right to make his way around the disturbed section of the path, but we eventually managed it.

Once beyond, Bembo merrily continued on his way back to home base, where Oliver slipped off, and Bembo went back into the rotation.

My mind has returned to that afternoon with Bembo often in the years since: how many times must have Bembo walked that path for it to become so implanted in him that no other path was possible? How many times after Oliver’s ride did he continue to do so? What become of him? Could he still be there, 9 years later, still walking the same path?

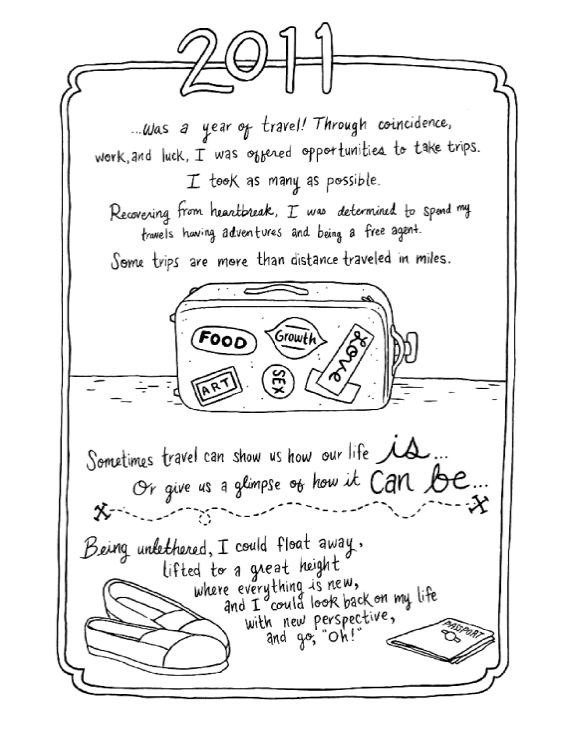

Oliver and I are reading the excellent Lucy Knisley book An Age of License, a “comics travel memoir” about her 2011 trip to Europe. The introductory page looks like this:

She writes:

“Sometimes travel can show us how our life is… Or can give us a glimpse of how it can be. Being untethered, I could float away, lifted to a great height where everything is new, and I could look back on my life with new perspective and go, ‘Oh!’”

Our ride through L’Esplanade with Bembo afforded me some of that new perspective: we can worry ourselves into repetitive ruts in life, ruts worn so deep that we hardly even know that they are there, as they come to simply resemble everyday regular life, “the way things are.”

And on occasion we come to a break in the path, a pile of bricks set there by others, and we’re confronted, suddenly, with the need to find a way around.

We can use that opportunity to squeeze around the pile of bricks and continue on the path, or we can use the opportunity to realize that perhaps we have the ability to set off down a different path and avoid the bricks altogether.

I am

I am