Since learning of the 11 escaped German prisoners yesterday, you’ve probably been waiting with bated breath for the rest of the story.

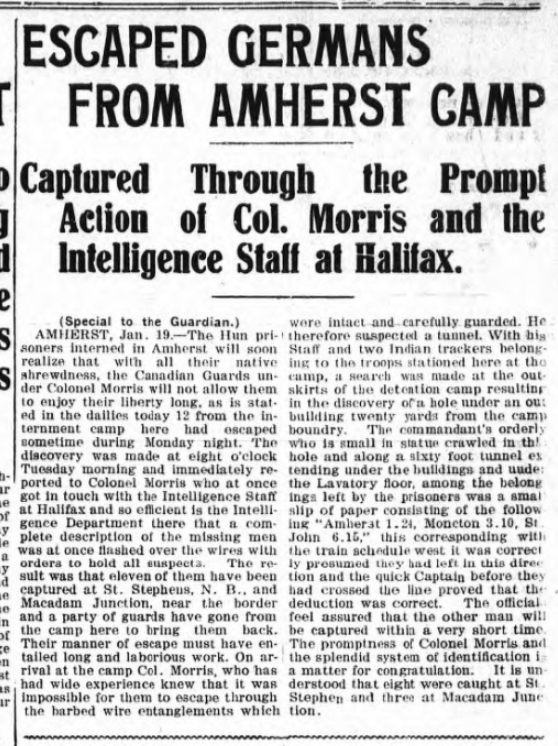

And in the following day’s paper came the answer: captured.

After he left Amherst, Nova Scotia, Leon Trotsky’s life – if you can believe it – got even more interesting.

As told in this tale of how his personal papers came to be owned by Harvard, he ended his life in Mexico, banished and largely abandoned by the world.

After making arrangements to sell his papers to Harvard, in 1940 they safely arrived there, and word was sent to him informing him of the arrival:

In the preceding months Trotsky had been deserted and renounced by some of his closest associates, including his Mexican protector and benefactor, the painter Diego Rivera. And in May, 1940, Trotsky’s home was subjected to an armed-raid, apparently at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. Around 4 a.m. a group of assailants broke into Trotsky’s home and pumped about 200 machine gun bullets into Trotsky’s bedroom. Although the attack left him miraculously unharmed Trotsky became increasingly concerned about his own safety and the safety of his papers.

After months of anxiety the telegram from Harvard must have been a great relief. Ironically, that same day, the very day he learned that his papers would be preserved and protected, Trotsky was assassinated. A man calling himself Frank Jacson, who had connived his way into Trotsky’s confidence, crept up behind him while he was at work in his study, and crushed his skull with an ice axe.

Of course between Amherst and Mexico there was also becoming Russian Commissar for Foreign Affairs, founding and leading the Red Army, etc. But that’s another story.

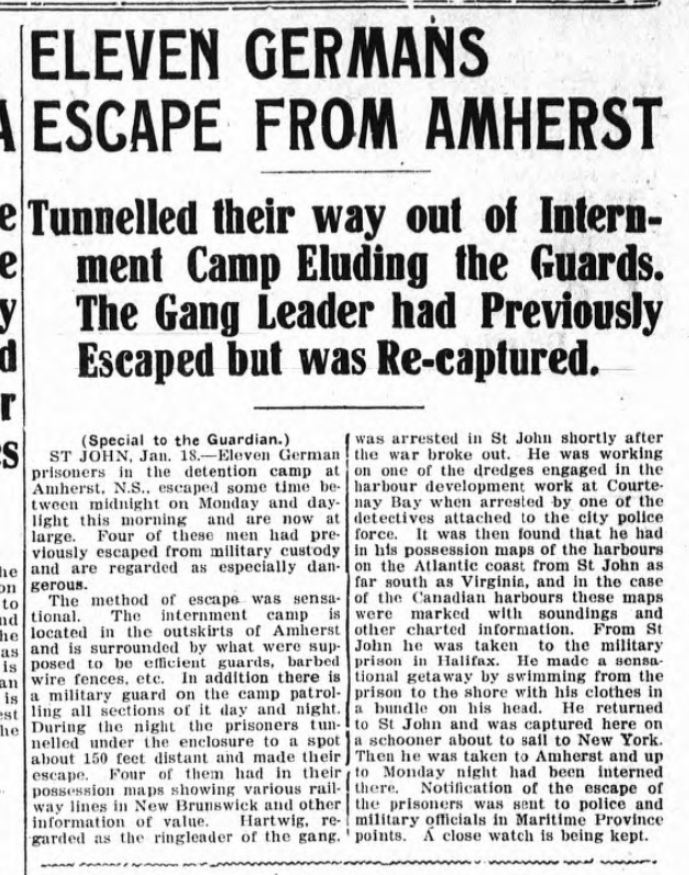

The front page story “Eleven Germans Escape from Amherst” from the January 19, 1919 edition of The Guardian caught my eye this morning:

The camp at Amherst is most famous for its most famous prisoner, Leon Trotsky; as he relates in his book My Life:

The Amherst concentration camp was located in an old and very dilapidated iron foundry that had been confiscated from its German owner. The sleeping bunks were arranged in three tiers, two deep, on each side of the hall. About eight hundred of us lived in these conditions. The air in this improvised dormitory at night can be imagined. Men hopelessly dogged the passages, elbowed their way through, lay down or got up, played cards or chess. Many of them practised crafts, some with extraordinary skill. I still have, stored in Moscow, some things made by Amherst prisoners. And yet, in spite of the heroic efforts of the prisoners to keep themselves physically and morally fit, five of them had gone insane. We had to eat and sleep in the same room with these madmen.

The tale of how Trotsky ended up imprisoned at Amherst is summarized well by Silver Donald Cameron.

At the time of this escape, though, all that was more than a year in the future.

The Guardian on today’s Twitter outage:

The company initially confirmed the outage by, somehow, tweeting, from its @support account. We were unable to see the tweet, because Twitter was down. Twitter emailed the text of the tweet to the Guardian, which read: “Some users are currently experiencing problems accessing Twitter. We are aware of the issue and are working towards a resolution.”

I love the “somehow.”

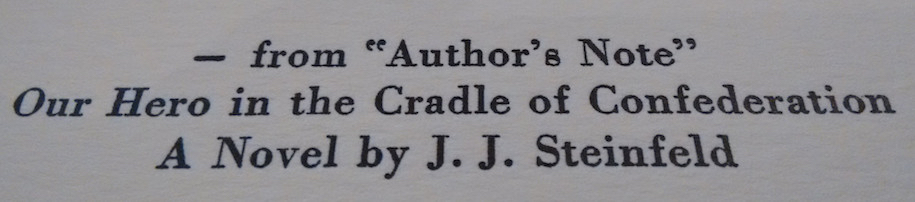

You write J. J. Steinfeld’s name like this: J. Period. Space. J. Period.

I know this because, two years ago, I set an excerpt of his Our Hero in the Cradle of Confederation in metal type and I needed to know.

It was the space that I was concerned about: I could have gone either way, but I deferred to J. J.’s preference and so J. Period. Space. J. Period. it was:

Even now I’m not sure that I took the right path. In The Elements of Typographic Style, Robert Bringhurst writes:

Names such as W. B. Yeats and J. C. L. Prillwitz need hair spaces, thin spaces, or no spaces at all after the intermediary periods. A normal word space follows the last period in the string.

So perhaps I should have mixed J. J.’s preference with some typographic wisdom and used a thin space rather than a full space? So J. J. rather than J. J.

But it is too late now and I must live with my decision.

This Wednesday, January 20, 2016 from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m., the aforementioned J. J. Steinfeld will launch his latest book, Madhouses in Heaven, Castles in Hell (buy it online) at the Bahá’í Centre, 20 Lapthorne Avenue here in Charlottetown.

Not only is the event a book launch, but it’s also an open mic night, where we members of the general writing public are invited to read 3 to 5 minute pieces of poetry or prose. I believe I might give it a go (readers can sign up at 7:00 p.m.). Perhaps I will see you there?

I’m in Summerside this afternoon, wearing my Hacker in Residence hat, to talk about open data with the Instructional Development and Assessment group in the Department of Education, Early Learning and Culture.

They have a beautiful office space in the Holman Building: bright, open concept, lined with substantial pillars: the kind of space you’d like your curriculum being developed in.

Two podcast episodes over the last month have opened my eyes to things I didn’t know.

First, that cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, savoy, and kohlrabi are all variants of the same species of plant, something revealed in an episode of the Surprisingly Awesome podcast.

Second, via an episode of the 99% Invisible podcast, that expiry dates on things like milk and yoghurt, have nothing at all to do with food safety (although it’s important to disclose that my partner [[Catherine]] insists that she’s been telling me this for years, and I haven’t believed her).

I am

I am