Eight months in, the government adds simultaneous sign language interpretation to Dr. Heather Morrison’s COVID-19 updates. Let’s hope this becomes standard operating procedure for all government events.

My plan to keep the outstanding bookstores of Earth alive through coronatimes continued with today’s arrival of Set Me On Fire: A Poem For Every Feeling, from Ella Risbridger, from Shakespeare and Company in Paris.

The delivery was lovingly packaged:

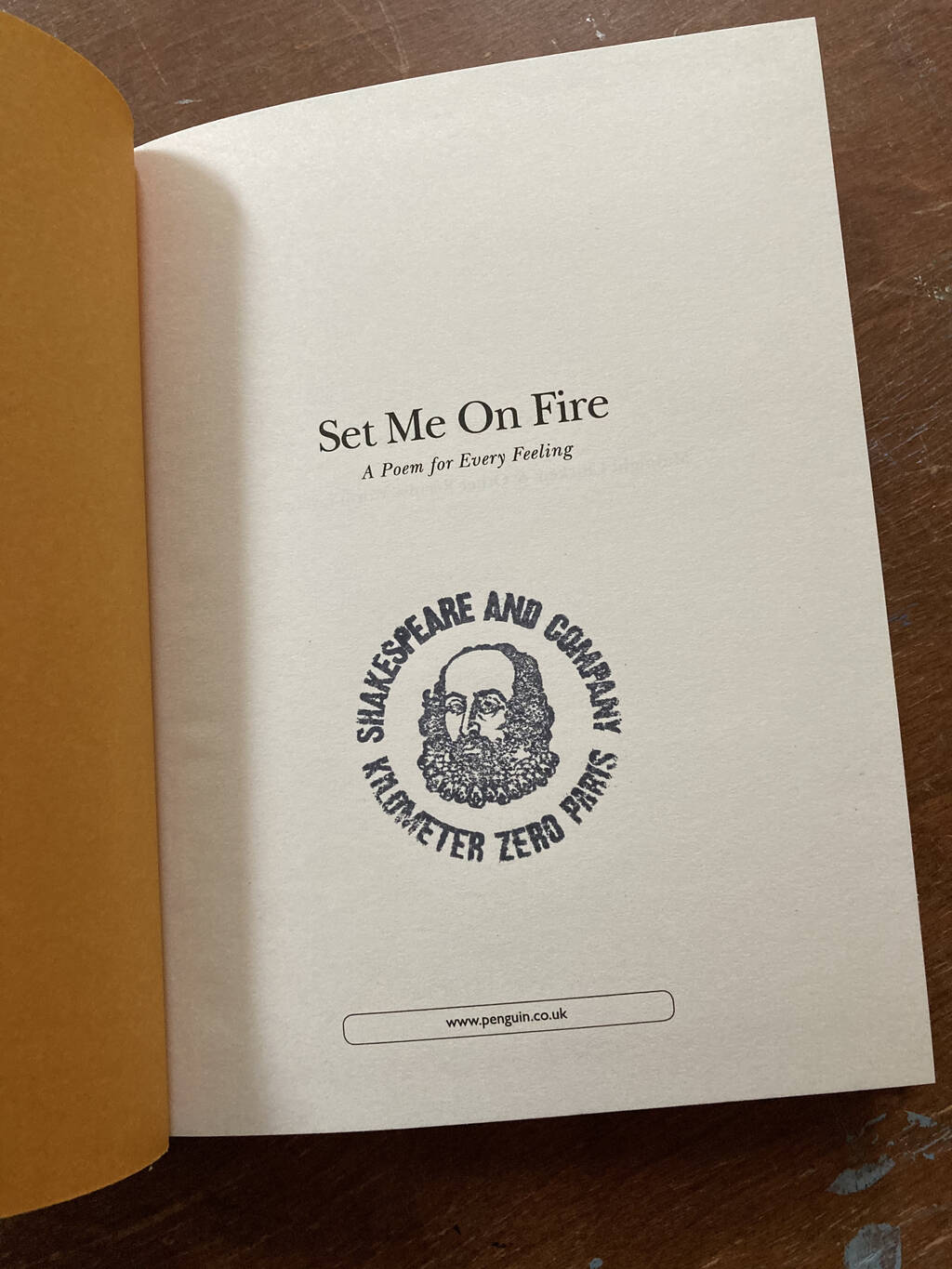

When I placed the order I ticked the boxes for two “upgrades,” the free “custom book stamp” on the title page:

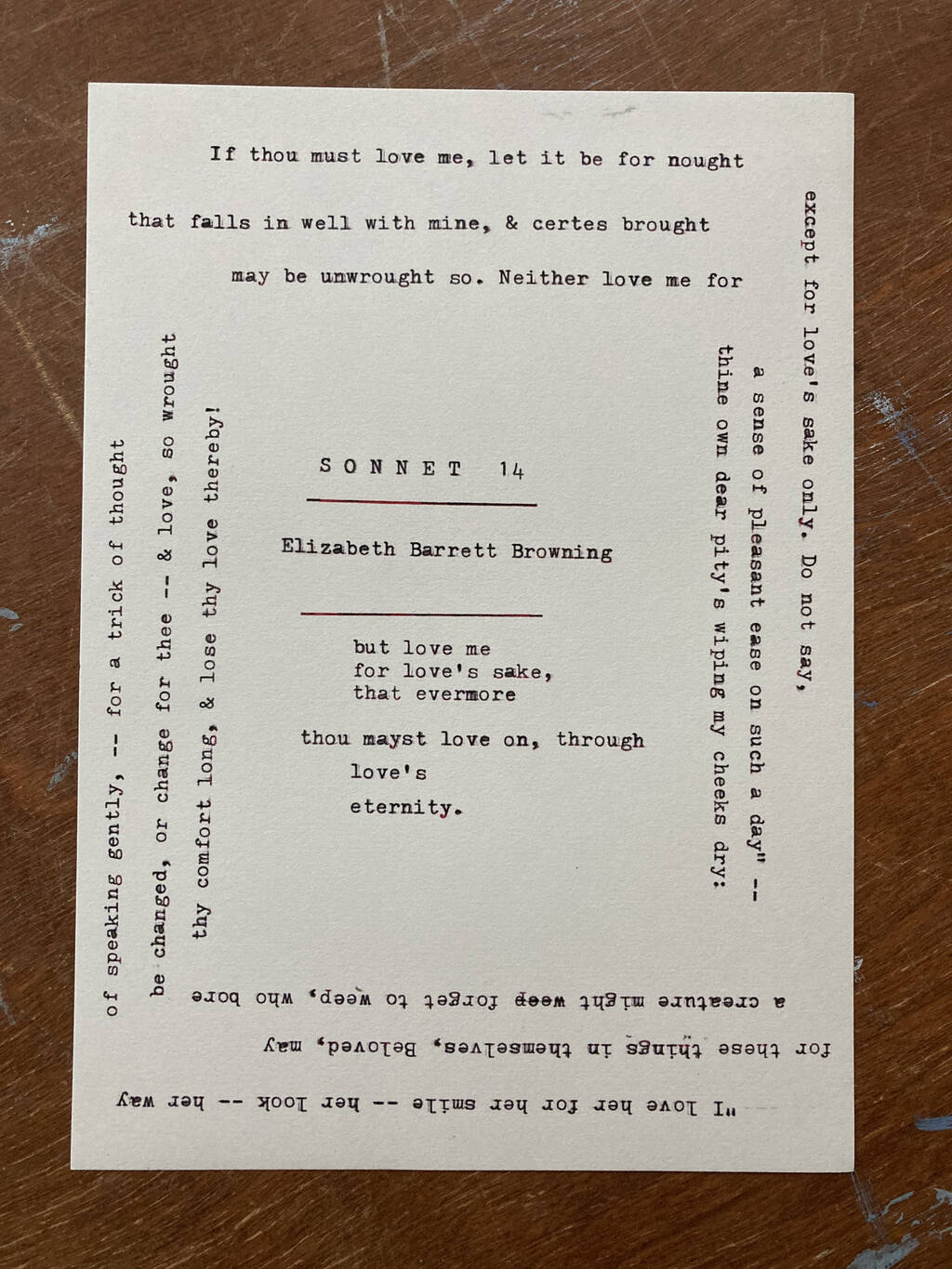

and the 83 cent “custom book poem,” a rendering of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 14:

I am a satisfied customer.

If We Make It Through December, a new album from Phoebe Bridgers, a Christmas album of sorts. The title track is a cover of the original from Merle Haggard.

If you like seasonally-themed Phoebe Bridgers tracks, her cover of John Prine’s Summer’s End is priceless.

Thanks to the generosity of our friends Oliver and Cheryl, Oliver and I had the pleasure of attending Superfest in October, on Zoom. One of my favourite parts of the weekend of films and panels were these comments from Thomas Reid, host and producer of Reid My Mind radio podcast, about what makes for good audio description:

Yeah. So let me break that down into some of the components of what I think is good audio description and talk about it in that sense.

Good audio description or AD has several components.

It’s about being respectful, meaning you don’t try to explain the plot because blind people can figure out the plot by themselves. You don’t over describe the movie. For example, when a phone is ringing, there’s no need to tell me a phone is ringing. I heard the phone. Right?

So you don’t censor those things you find offensive. Because if it’s on the screen and if it’s in the story, we should know about it. Right? Good AD means good audio. I shouldn’t have to ride the volume control up and down to hear the audio describer and then higher or lower to hear the actual film.

You take the time to make that audio right. Good audio description doesn’t step on dialogue. Right?

At its core it’s about providing access to the visuals. Those who see the film learn certain information about a character that can be their color, sometimes ethnicity, or race. Other indicative information about the person, it can be relevant to how they interpret that film.

Blind viewers also should have access to that information.

It’s worthwhile reading the entire transcript, as Reid goes on to talk about the representation of race in audio description and reflects on the audio description of the film we’d just all watched.

There’s also a two-part series on Reid’s podcast, Flipping the Script on Audio Description (Part One, Part Two) that offers many additional insights.

In the spirit of Reid’s words, I’ve been working to pay more attention to the “alt tags” in the images I include here on the blog, using the same points to guide me.

My mother grew up in a building on 233 5th Avenue in Cochrane, Ontario, a former bottling plant that was converted into apartments. You can see it in Google Street View, albeit from a distance:

The building is in the distance because the Google Street View coverage for Cochrane, inexplicably, does not include 5th Avenue:

Here’s a “look around” view from Apple Maps, which does cover 5th Avenue:

Here’s a photo, closer up, that my mother took on a trip to Cochrane in 2015:

I have many fond memories of visits to that house; strongest among them is the feeling of hiding under my step-grandmother’s fur coats in the upstairs apartment during games of hide and seek with my brothers.

Last week I wrote about the Cochrane, Ontario typhoid epidemic of 1923, after reading my great-grandfather Edgar Caswell’s reflections on it. Today, that’s to Dick Bourgeois-Doyle’s biography of Edgar, I learned that typhoid affected our family directly.

First-affected was Edgar’s brother Bob:

Dad they begun the annual transport of stones in December 1905 and been away from home at a distant quarry, Bob Caswell might have tried to shrug off his sore throat and fever and kept working. But it was the slow time before Christmas, and the family insisted he rest while they sent word for a doctor to come up on the train from Ottawa to check his tonsils. Bob was only thirty-seven years old. His death would be formally attributed to typhoid fever presumably due to drinking “dirty water.” But for over a century, a persistent story flowed through the family that tied Bob’s death to the infections resulting from a sloppy, candlelight, kitchen-table surgery performed by the Ottawa doctor, who had stopped at the pub on the way to the farm. Either way, Bob’s death from infection was miserable. It was the days long before antibiotics and sober doctors or not, there was little that could be done in such circumstances but to hope, pray, and wait. the family felt powerless.

Eight years later Edgar was stricken himself:

At this time in 1913, Ed Caswell was back in Cochrane recovering from typhoid, the disease that had reputedly killed his brother just eight years earlier. Ed picked up the disease trying to make some extra cash working out of town with construction crews on the transcontinental. The diarrhea and fevers of typhoid infection are not helped by the lack of first aid and the rugged ambiance of bugs, heat, tents, and cots out on the rail lines.

Bourgeois-Doyle writes, later, about the affect of typhoid on Edgar:

Of course, ed Caswell had special reasons to be sensitive to the threat aside from his official duties as a municipal manager. The typhoid-linked death of his best friend, partner, and brother Bob in 1905 left an enduring mark on Caswell’s soul, and Ed’s personal brush with typhoid led him into his job with the town and ultimately into his role as fire chief. events flowing from typhoid defined almost everything about Ed’s life now. He was, therefore, among the most vigorous voices warning residents of Cochrane against taking drinking water from the small lake north of town, the one deceitfully and enticingly named “Spring Lake”: the one just next to the town’s lake-like sewer pond. People usually drew their water from a chain of springs near the lake. but when the springs ran low or were clogged by ice, it was just too easy to dip a bucket into the open water of Spring Lake. In the early months of 1923, the sewer lake backed up and overflowed, possibly due to blockages of ice or unexpected runoff. Its toxic waters flowed along the ground and dripped into water that too many people were drawing for their homes. The town had been booming and growing, and this meant greater and greater water consumption.

Today the Town of Cochrane has a robust and, by all appearances, well-monitored and regulated water and sewer utility.

If you’re interested in learning more of the story of Edgar Caswell, track down Stubborn: Big Ed Caswell and the Line from the Valley to the Northland.

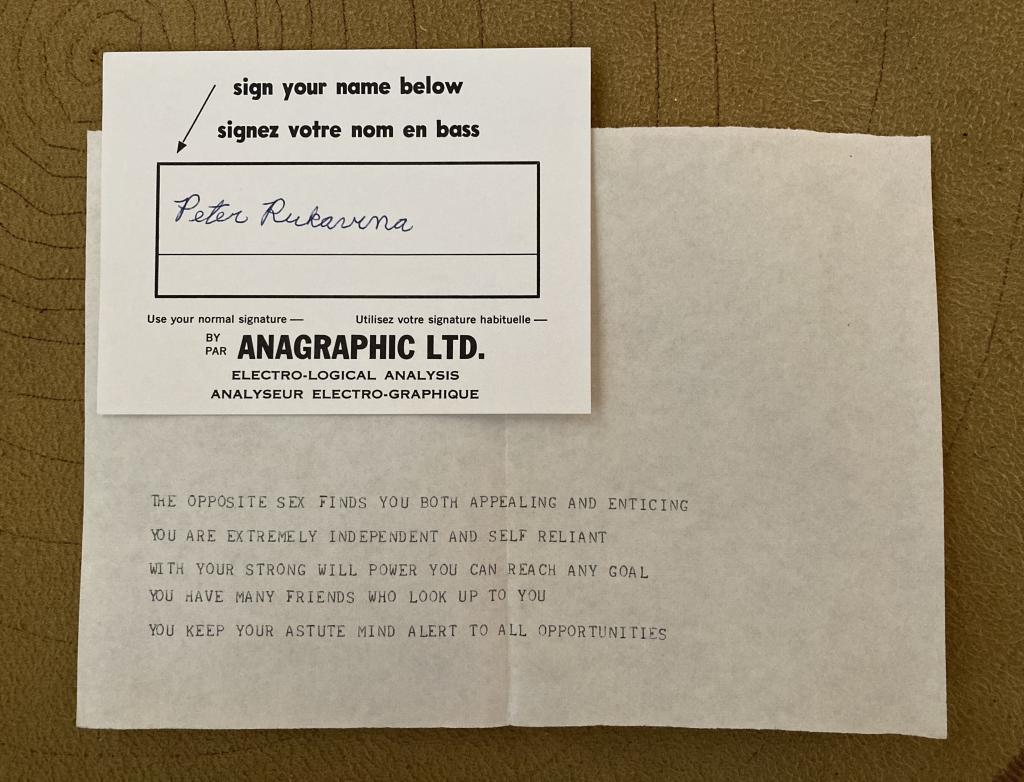

I found this in a shoebox of things from my childhood. I’m fairly certain it came from a booth at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto in the early 1980s.

Since that time I’ve dramatically changed my signature, so I assume none of the analysis stands.

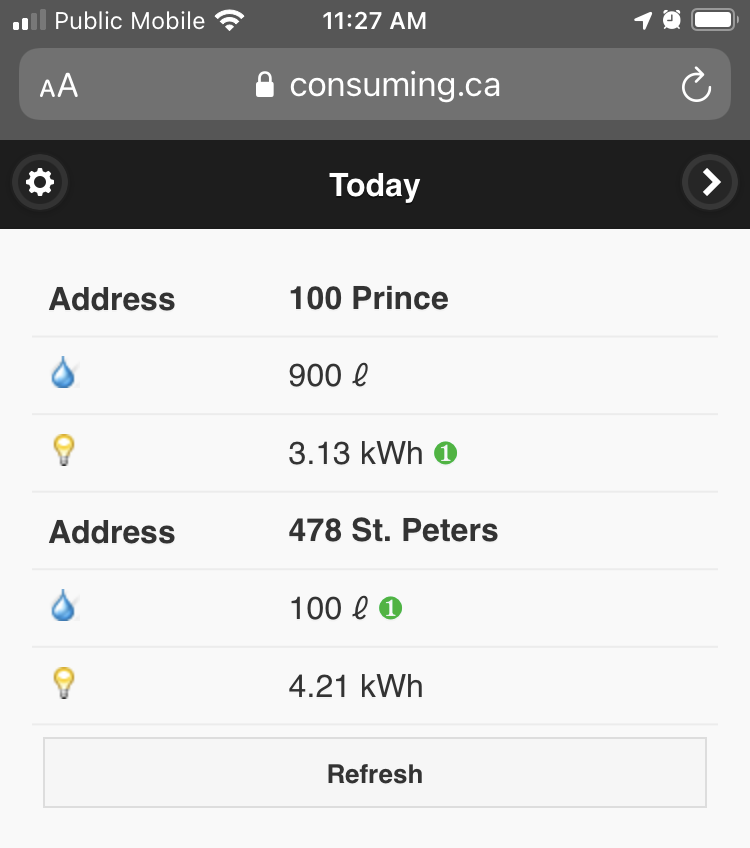

Someone, let’s refer to him as “the other person who lives in this house,” left the tap running in the downstairs sink last night, something I’ve didn’t discover until this morning, meaning it was running on a slow trickle for 12 hours. 800 litres of water was wasted.

Given that this is data that’s logged every few minutes, it occurs to me that I should send myself alerts when aberrations like this show up, before they have a chance to go on for so long.

The near-identical widgets for date and weather on my iPhone’s home screen are a constant source of confusion for me. Today, at least, they spell a Rush album.

I am

I am