With network television on hiatus over the holidays, we turn to Netflix for our entertainment. Here’s what I’ve enjoyed so far:

- The Hour — A 1956 period drama set at the BBC. I’d describe it as “Mad Men in London,” but it’s far more interesting then that, both because of its insights into politics and class, and because the cast is far more well-rounded. There is, however, about just as much smoking and drinking.

- Transsiberian — Started watching it months ago and abandoned it. For some reason it seemed more compelling last night. Woody Harrelson and Emily Mortimer take the train across Siberia where they run into Ben Kingsley. Murder and mayhem ensue. Not a great movie, but if you’re interested in trains and/or Russia in winter it has its moments.

- Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock? — A well-produced documentary about a truck driver who finds what she believes to be a Jackson Pollock painting in a thrift store and her attempts to get it authenticated. Read The Mark of a Masterpiece from The New Yorker for some background before you watch.

- The Yes Men Fix the World — If you enjoyed the 2003 movie The Yes Men, you’ll likely enjoy this too: although it’s slightly less earnest and a little more goofy, it features more of the same news-hoaxing-antics of The Yes Men, this time focusing on everything from Bhopal to Katrina to producing a wishful-thinking issue of The New York Times.

- Designing a Great Neighborhood — A poorly-produced, rather boring documentary about a very interesting project to transform a former drive-in movie property in Boulder, Colorado into an ecological community. If you can bear to sit through it there’s some interesting material covered.

There’s a lot of chaff in the Netflix selection — seemingly endless direct-to-video movies that involve some combination of babysitters and the occult — but it has an uncommonly strong documentary selection, and next to the wasteland that is our local cable company’s “On Demand” selection, it’s positively brimming with content.

From Wayne MacKinnon’s book The Life of the Party: A History of the Liberal Party in Prince Edward Island:

The 1966 Provincial election in Prince Edward Island remains perhaps as the most novel in Canadian political history. It ended (after a series of close recounts) in a tie, and it was left for a deferred by-election in one district to determine a winner.

The reason for the deferred by-election was the death of 1st Kings district Liberal candidate William Acorn after the writ had dropped but before election day. The was an era when the Island had 16 two-member districts; on May 30, 1966 there was a general election in only 15 of those districts, and the result was 15 Liberal members and 15 Conservative members.

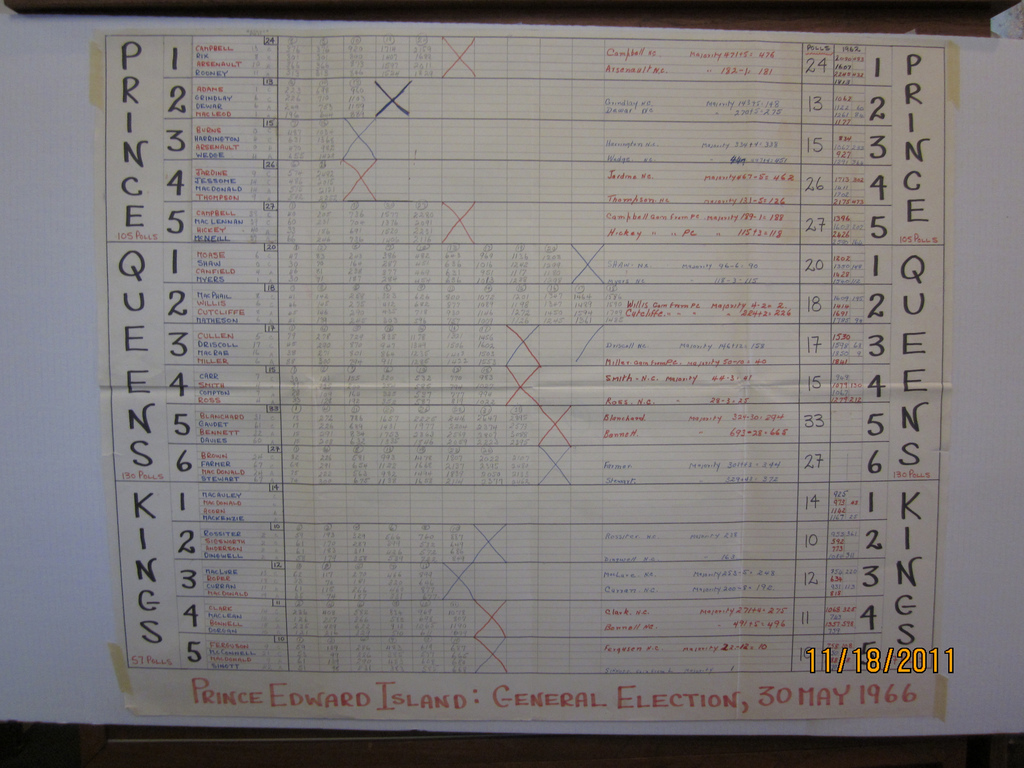

This morning at Elections PEI I got a look at the sheet used to tabulate the results of that election; you can see 1st Kings is blank, as no election was conducted there on regular polling day:

The Chief Electoral Officer’s report picks up the story from there:

A writ was forthwith issued, setting July 11, 1966 as the date for the deferred election in the First District of Kings.

What followed, according to Francis Bolger’s Canada’s Smallest Province, was an orgy of patronage in the district:

Some observers estimated that the crucial constituency received thirty miles of paving in the midst of the pre-election fever. One local citizen with a sense of humor was moved to erect a prominent sign which read: “PLEASE DON’T PAVE. THIS IS MY ONLY PASTURE.” It was widely reported that the government was adopting the slogan: “If it moves, give it a pension, if it doesn’t, pave it!”.

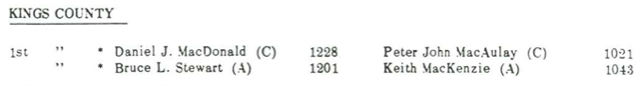

In the end, it didn’t work: 1st Kings returned two Liberal members, Daniel J. MacDonald and Bruce L. Stewart, with margins of victory of 207 and 158 respectively, suggesting that there’s only so much you can achieve through paving.

As a result of the win, Canada’s youngest political leader, Liberal Alex Campbell, replaced Canada’s oldest, Conservative Walter Shaw, as Premier. Campbell would go on to transform Prince Edward Island more dramatically, perhaps, than any of his predecessors.

Senator Percy Downe posted the text of a 1990 New Year’s Eve address to the nation by the late Václav Havel; it’s a stirring speech, the heart of which, for me, is:

The previous regime — armed with its arrogant and intolerant ideology — reduced man to a force of production, and nature to a tool of production. In this it attacked both their very substance and their mutual relationship. It reduced gifted and autonomous people, skillfully working in their own country, to the nuts and bolts of some monstrously huge, noisy and stinking machine, whose real meaning was not clear to anyone. It could not do more than slowly but inexorably wear out itself and all its nuts and bolts.

When I talk about the contaminated moral atmosphere, I am not talking just about the gentlemen who eat organic vegetables and do not look out of the plane windows. I am talking about all of us. We had all become used to the totalitarian system and accepted it as an unchangeable fact and thus helped to perpetuate it. In other words, we are all — though naturally to differing extents — responsible for the operation of the totalitarian machinery. None of us is just its victim. We are all also its co-creators.

We would all do well to consider these words as we think about your own society and how it operates.

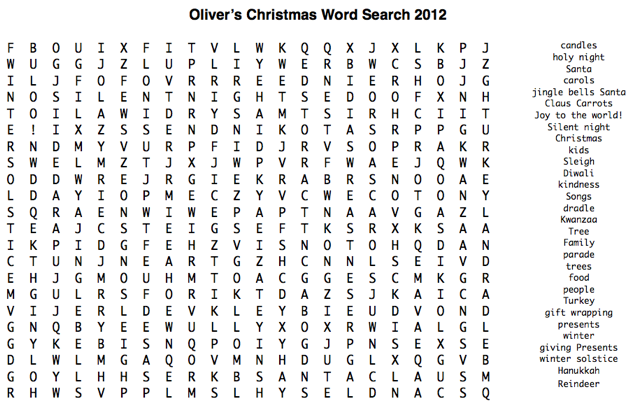

Oliver is quite resourceful when it comes to navigating the alleys of the Internet, and his creations are a constant source of surprise and delight. Here’s a word search he made for Christmas (you can download a printable PDF for your hometime enjoyment).

This photo of my mother and Sergey in my parents’ Ontario kitchen having a Skype video chat with Sergey’s wife Leisa in her apartment outside of Kiev in Ukraine could very well have been featured in an AT&T advertisement in 1960 anticipating a rosy electronic future:

So much digital stuff is happening every day that it’s easy to lose track of just how truly amazing this is: video traveling, in real time, halfway around the world, from kitchen to kitchen, on a magic tablet you can hold in your hand. For free. Amazing.

The Charlottetown Festival announced yesterday that it’s cutting the size of its orchestra from 19 to 13. My friend Dale eloquently dicusses all of this from the point of view of a musician in the pit, and I highly recommend that you read his post.

I’m no great fan of Anne of Green Gables — The Musical — I am a victim, alas, of being part of the chorus for a staging of the musical when I was in grade 3, and so I have a strong involuntary flight response whenever I hear the stirring refrain “Anne of Green Gables, never change.”

But I’m the father of a die-hard fan — Oliver has seen the musical every summer for as long as I can remember — and as much as it pains me that Anne is the primary artistic output of “Canada’s National Memorial to the Fathers of Confederation,” I recognize the centrality of the musical to the cultural and economic life of the city and the province, and so, despite my artistic misgivings, I am forced to admit that, net-net, it’s a good thing.

I also have a lot of friends who are employed, directly or indirectly, by the musical’s annual staging: technicians, stage crew, carpenters, designers. And musicians. Indeed if you you want make a living as a professional musician on Prince Edward Island, the Festival’s pit is about your only option; and the contribution of those so-employed to the musical life of the province is inestimable.

So when the Charlottetown Festival cuts 6 positions from its orchestra, I pay attention: I’m concerned for friends, concerned for the musical itself, and concerned for what the unanticipated side-effects of such a cut will be for the Island.

What really bothers me about the announcement of this cut is the way that it was spun by the Confederation Centre administration: CEO Jessie Inman was quoted by the CBC saying:

“I think the magical theatre experience that we have offered to our patrons of Anne — The Musical for so many years will be maintained. The integrity of that score will be maintained, and I don’t believe that our patrons will have any lesser experience,” she said.

Which I read as “we never really needed those 6 other musicians anyway, and nobody will notice they’re not there.” Setting aside whether this is true or not, this shows tremendous disrespect to the players whose positions will be cut: if there will be no “lesser experience,” then, presumably, they were just dross taking up space in the pit.

It’s fine to spin the “magical theatre experience” bullshit to bus tour companies, but this kind of talk has no place when addressing so serious a cut to an Island audience: these musicians are our friends, our neighbours, our music teachers, the parents of our kids’ friends, the people we see on the street every day. Whether or not economic realities of the Centre’s operation require this cut, Ms. Inman owes all of the musicians employed by the Charlottetown Festival an apology for her callous disregard to the role they have played in the success of the musical and in their importance to the Island community.

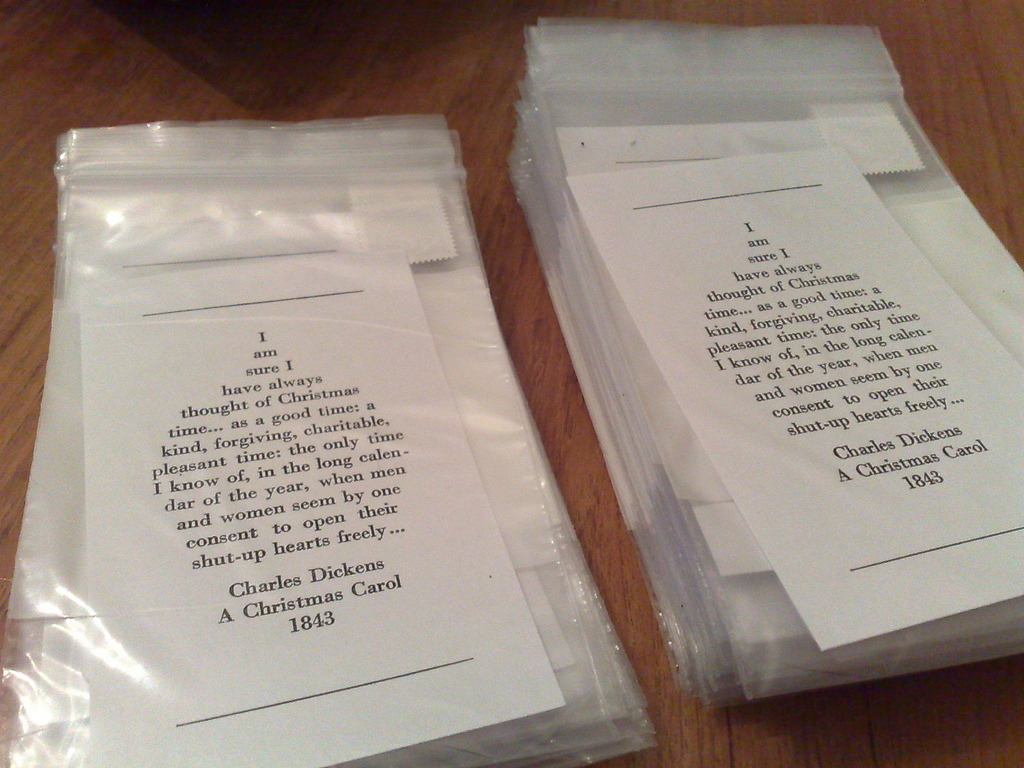

After a lot of printing and labelling and stamping, 64 copies of the 2012 Christmas Card went out in the mail earlier this week. I used small poly bags as envelopes, sticking a white mailing label and stamp on each and inserting the card so that it faced out through the transparent back. While I made the Canada Post mailing deadlines for all Canadian locations (December 15), missed the US deadline (December 13) by a day, and the deadline for Europe, Australia and Taiwan by almost half a month. So not everyone will get something for Christmas, but some will and the rest, well, you can hold on to things for 2012. Just out of interest I’d appreciate it if you’d add a comment to this post when and if you do receive your card.

In last week’s accidental destratification episode I found myself at a house party with the city’s hipster intelligentsia nervously clutching a glass of red wine while listening to Foster the People on the hi-fi and trying not to flash entirely back to the social suicides of 1980. I felt old and decidedly unevolved.

This week, however, destratification alighted on my shoulders again, and the results were decidedly better.

Every year the Rodd Charlottetown Hotel fêtes its loyal customers with a Christmastime buffet and bar in the lovely Georgian Room. This year, by dint of my role as secretary to the PEI Home and School Federation, I was invited to attend (the Federation holds its annual meeting there every year, so we are, indeed, a loyal customer).

It turns out that the other loyal customers all wear suits. And are the rich and powerful among us. Judges. Doctors. Tycoons. Moguls. The people, in other words, liable to say “why don’t we do it at the Rodd’s” when they’re at meetings discussing, say, where to hold the annual White Ball.

While I might normally, as a dungaree-wearing ne’er do well, feel like uncomfortably like a fish out of water among such suit-wearing oligarchs, in this case the accidental social destratification paid off: because, outside of my home and school brethren, I didn’t really know anyone there, I was free to graze amply at the lavish buffet stations, most of them almost completely untouched, while the socially well-connected were trapped in their vortices of social obligation: it’s hard to break away and grab another helping of cajun salmon when that guy you’re trying to cultivate a deal with is talking your ear off about the Dow Jones Industrial Average (note my complete lack of awareness of what important people talk about).

And so eat I did.

I started off with an appetizer-sized portion of grilled scallops served on a bed of risotto. It was fantastic: perfectly cooked, served at the perfect temperature.

Next it was the smoked salmon table, where all the fixings required to create a custom-tailored smoked salmon masterpiece were on tap: rye bread, dilled cream cheese, capers, tomatoes, lemon wedges. I returned to this well several times and was seemingly the only one who did, as the table seemed hardly touched even as things were winding down.

Over to the fruit table: grapefruits, kiwis, oranges, starfruits, mangoes. Accompanied by tiny desserts: tarts, squares, and the like.

Back to the hot line for the aforementioned cajun salmon, served fresh-grilled on a bed of rice with a perfect white sauce.

On to the cheese table: smoked cheese, swiss cheese, cheddar cheese, gouda cheese.

Back to the fruits on the way out.

I did, in fact, get a chance to have a nice conversation with Shirley Jay (our Executive Director at Home and School) and her husband Allan in amongst all that eating. And I did actually wave hello to a few people that I do know — I’m not a complete dungaree-wearing hermit after all.

But I emerged more well-fed and satisfied than most, I think. And I have my dorkiness to thank for it.

The Dow was up 45 points, by the way, closing at 11868.

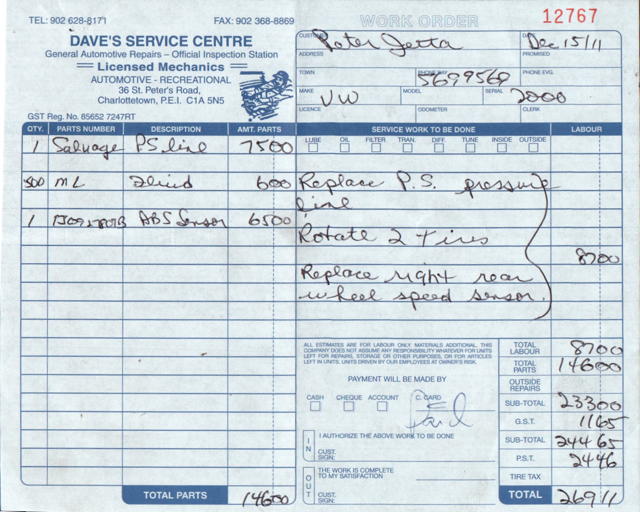

When we last discussed my ailing Volkswagen Jetta you may recall that it was in the context of the $3,242.94 estimate to repair it from Brown’s Volkswagen.

For additional guidance on this matter I turned to Craig Wilson who, 10 years ago, recommended the dealer, then called Sherwood Volkswagen, as a place to buy a new car. I’d never met Craig, but I took his advice, and I did, indeed, enjoy the purchase and service from Sherwood Volkswagen back in the day. So I reasoned that it would be a good time to check in with Craig to see where he goes these days for service.

Craig gave a ringing endorsement to Dave’s Service Centre at the corner of Allen Street and St. Peters Road. I’ve driven by the place a thousand times, but I’d never been in. Today after dropping Oliver off at school I drove the Jetta over for them to take a look at. The result:

That number over there in the bottom right, $269.11, that’s the price, parts and labour, Dave’s Service Centre charged me to fix everything but my small exhaust leak (which I didn’t ask them to fix). Indeed it includes an additional issue — a wonky ABS sensor — that wasn’t an issue until this morning.

The $586.80 that Brown’s quoted for power steering lines? Turns out I only needed one of them, and Dave’s happened to have a salvaged one around which they sold to me for $75. The shimmy in the front end I’d asked Brown’s about? Brown’s solution — replace the front struts — was quoted at $709.89. Dave’s found the problem to be simply a scalloped front tire, which they rotated onto the rear of the car, no parts needed.

Now it’s not really fair to say that Brown’s quoted me $3,242.94 to do the same thing that Dave’s did for $269.11, because Dave’s did different things. The point is that Dave’s appears to exist in the real world of solving problems so that cars work better, as opposed to the “how much can we figure out wrong with this car to wring the absolute largest margin out of this guy” world that Brown’s VW lives in.

Dave’s Service Centre today becomes my go-to place for auto repair: they were friendly, efficient, explained everything to me clearly, showed me the old parts, and sent me on my way. Recommended (I should really send Craig a $3,000 bottle of scotch, shouldn’t I).

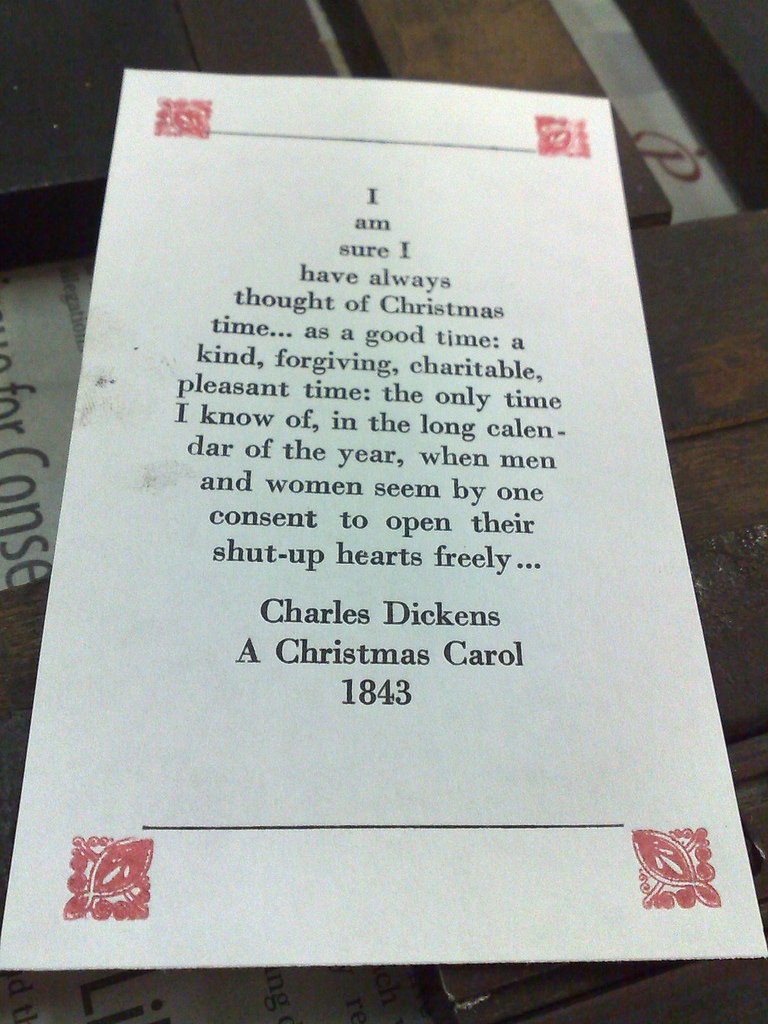

Tonight was my first night in the basement of The Guild taking the new Golding Jobber No. 8 letterpress for a ride, printing something actually useful (or, at least, something actual): it was printing night for the 2012 Christmas cards.

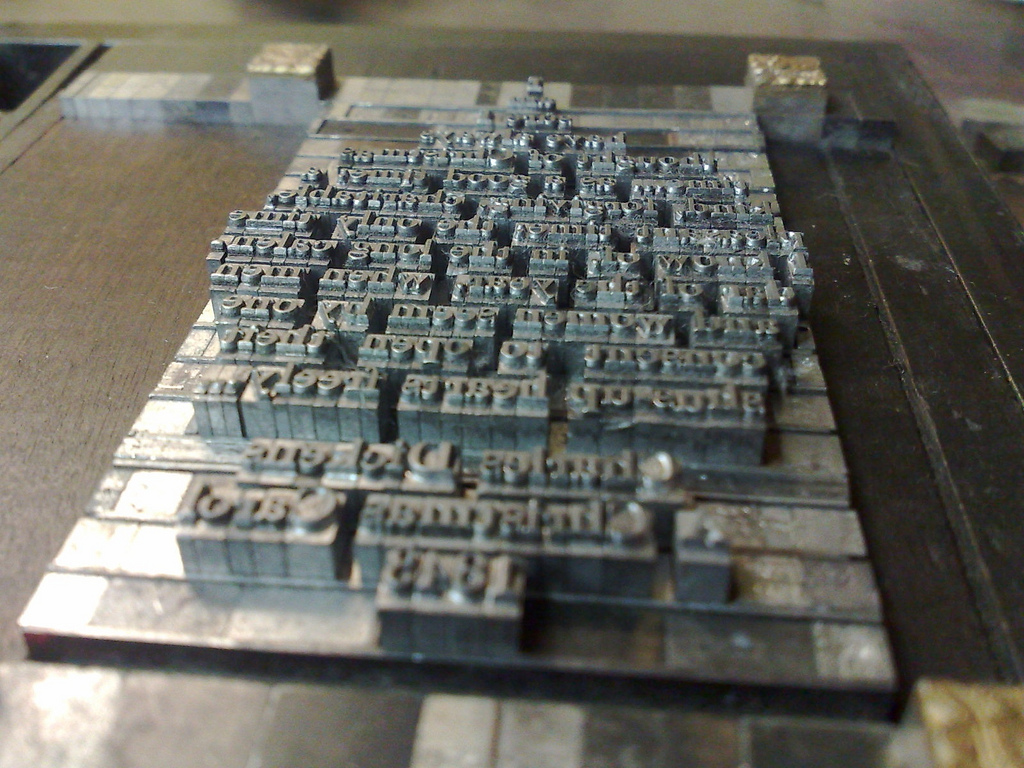

Over the weekend I set the type, a passage from A Christmas Carol. The original plan was to set it in the shape of a Christmas tree, but I couldn’t make that work on the 3”x5” index cards, so I shortened things up and set it as more of a candle or ornament shape that looked like this:

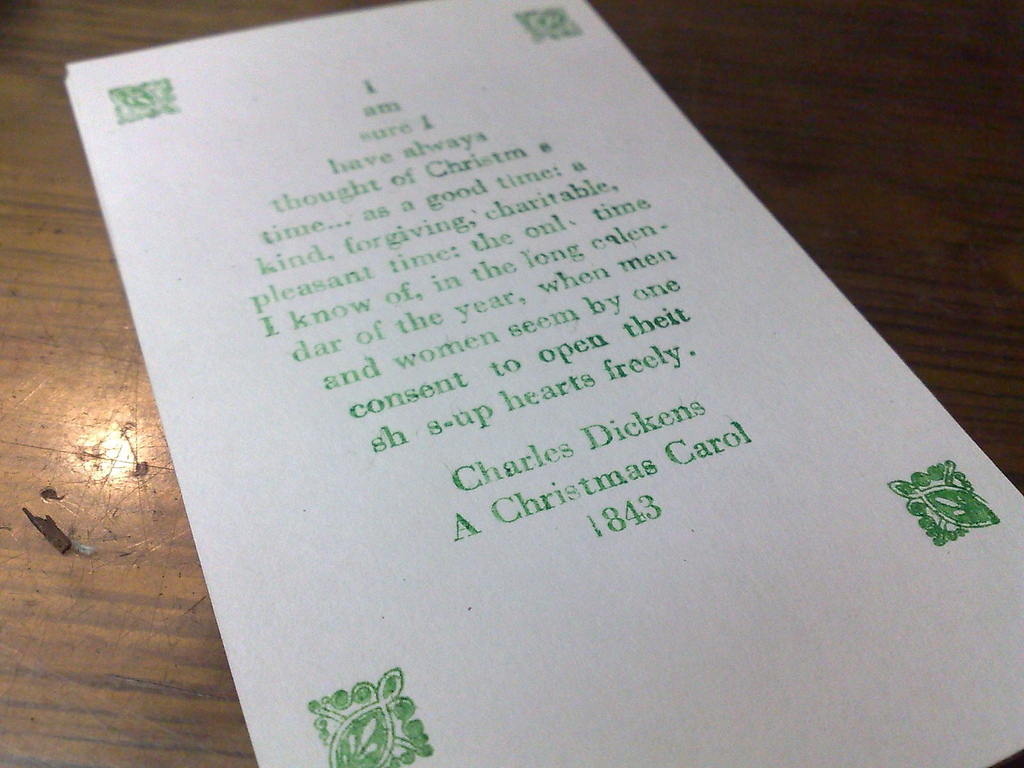

I made a proof with a rubber stamp, noting and fixing some issues (the “shut-up hearts” was set as “shus-up hearts” with a non-printing “u” for example):

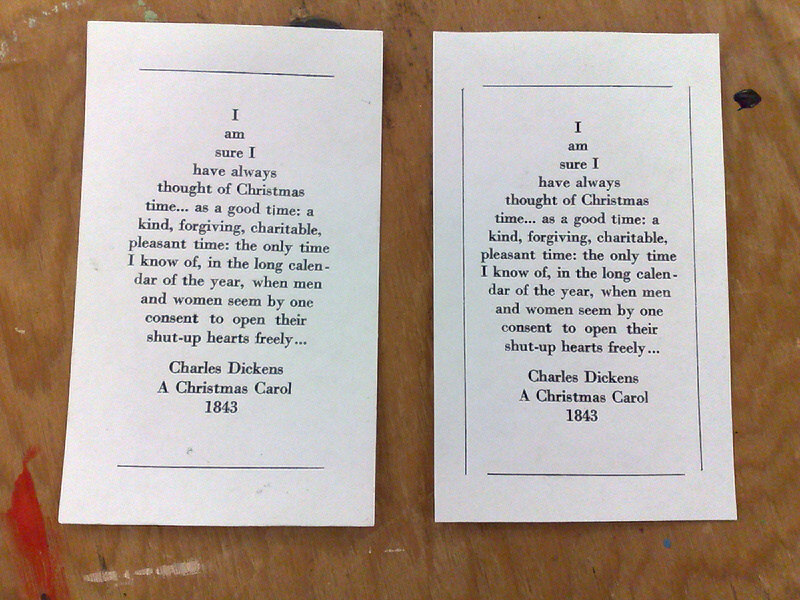

With the job proofed, I set it in the larger Golding Jobber chase and, tonight, headed down to The Guild (I really do need to get “composing” and “printing” under the same roof sometime soon!). The original plan was to print the text surrounded by four lines, with ornaments, printed in red, in each corner. The vertical lines, however, proved problematic: I couldn’t adjust the job so that they were equidistant from the right and left edges, and I ended up not liking the look of the lines in any case. So I removed the vertical lines and left the horizontal ones, which made for a dramatic improvement:

I then used the awesome power of the Golding Jobber to run off 100 of these in about 10 minutes. I didn’t take very long to get into a good rhythm (and to realize that I need to recreate the old wooden “shelf” that holds work in front of the press). And then I had a pile of 100 of the black:

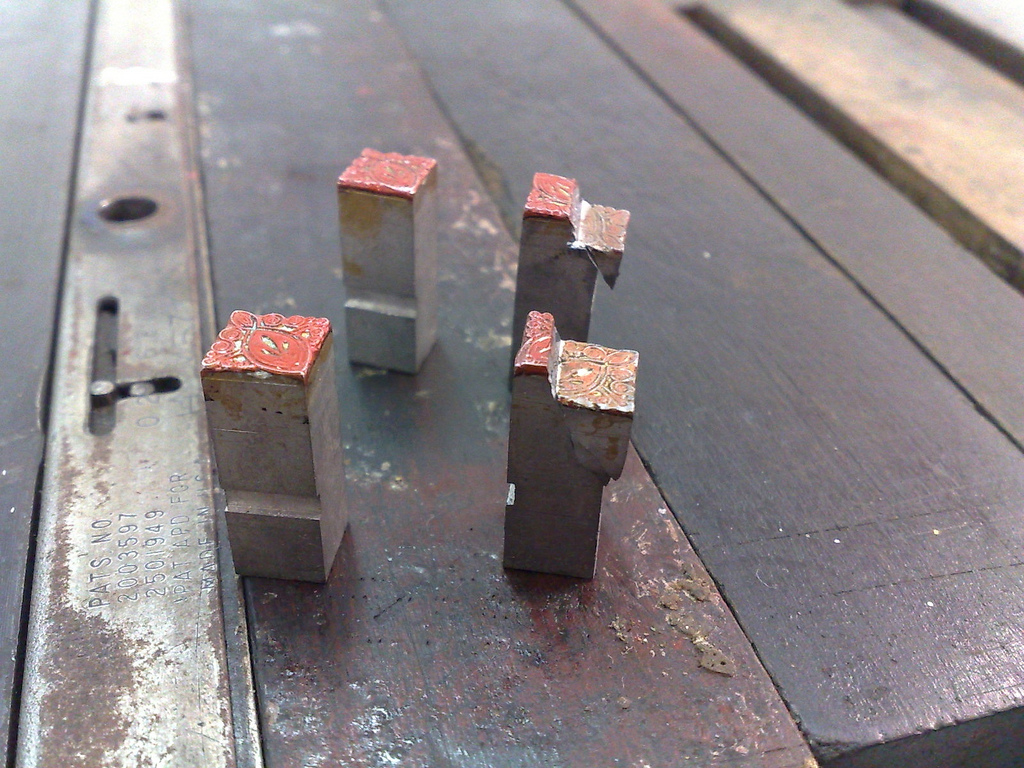

Next, I removed the black type from the chase and set the red ornaments in, set to appear in the four corners just touching the black horizontal lines. Things were going so well by this point, that something was bound to go wrong. Here’s as far as I got with the red:

With everything aligned almost perfectly, I moved the metal “paper holders” that swing up and down to hold the paper in place on the press a little closer to the job. I was sure that they weren’t too close. I was wrong. The result: on the next run there was a metal-metal-paper sandwich that crushed the right-hand ornaments:

In the end, with no replacement ornaments and the evening drawing to a close and Christmas only 11 days away, I had to settle for a black-and-white job and leave the fancy two-colour job-with-ornaments until another year.

The silver lining in this experience: it was the ornaments, not my nose, fingers, ears or hands, that got crushed. And I learned another layer of awesome respect for the crushing power of the press, something that I’m sure will stand me in good stead.

So you 66 Mail Me Something subscribers, your red-free cards will be in the mail to you on Wednesday; depending on your location they’ll arrive before or after Christmas. Enjoy.

I am

I am