Michael Enright interviewed Preston Manning this morning on The Sunday Edition about populism.

I’ve always had a lot of time for Manning, even though, on paper, our politics don’t overlap very much; he made an excellent point in this interview, one that resonates with something I’ve been thinking a lot about in the age of Trump:

Enright: How do we gauge or measure the fact that people, elites so-called, are not listening to what the grassroots are saying?

Manning: Well one way, Michael, is to look at their communication style. I’m not knocking elites, I’m just trying to reflect on the points you’re trying to get to. Why is it that so many people no longer listen or are impressed by them. And the communication style of elites, whether it’s academics, or high business executives, or government executives, is that they’re source-oriented communicators. They say what they want to say, in the language they want to say it, with the media that they are most comfortable with, and that’s a perfectly fine method of communication when you’re dealing with your peers. But the opposite of that is a receiver-oriented communicator, who doesn’t start with what I want to say, and my view, who starts with “who are these people in this audience, what are they thinking, what are their attitudes, what is their vocabulary, what is their preferred media.” Taking that into account, then getting around to saying what you want to say. The later one is the style of a small-d democrat politician; the other is a different style that doesn’t resonate with rank and file people.

So much of what rankles me about how our democracy operates comes down to this notion of communication style. Here, for example, is a sentence pulled from the 2016 Prince Edward Island Budget Address by Hon. Allen F. Roach, Minister of Finance:

At the same time, we must remain mindful of the continued volatility in the global economy. Vast fluctuations in the pricing of resources and other market conditions have placed pressure on government and private industry alike. These pressures, in turn, have impacted both personal and public finances. We, as Islanders and as a Government, are not isolated from these economic realities.

The budget address is the most concrete statement that government has to make each year about how it will govern.

And yet what does that sentence mean?

Nothing. It is entirely without meaning for the regular everyday person–Manning’s “rank and file people”–among which I count myself. While “vast fluctuations in the pricing of resources and other market conditions” might mean something to an economist, to most people this sounds like “blah blah blah, blah, blah blah.”

Compare this to a section from President Donald Trump’s inaugural address:

From this moment on, it’s going to be America First.

Every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs, will be made to benefit American workers and American families.

We must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies, and destroying our jobs. Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.

I will fight for you with every breath in my body – and I will never, ever let you down.

In both cases the speakers are making a macroeconomic point; setting aside whatever you might feel about Trump’s “America First” approach, he is speaking in clear language that anyone can understand. Is it any wonder that he’s capable of making a connection with many electors, even those who don’t share his politics.

You might argue that Manning’s “receiver-oriented communication style” is nothing more than “telling them what they want to hear,” and certainly in Trump’s case there appears to be much of that; but note that Manning finishes his description with “Taking that into account, then getting around to saying what you want to say.”

He is, in other words, saying “listen, then talk” and, further, “when you talk, talk in a way that people can relate to.”

And that doesn’t seem to be asking too much of those who we charge to conduct the public business.

Our current administration here in Prince Edward Island has suggested in past that it will heed this notion; in one of Premier MacLauchlan’s first statements upon assuming office he summarized this as follows:

We must continuously look for new ways to obtain input from citizens and the community, to inform government decisions and priorities. By listening carefully to citizens, we will make better decisions about public policy and its administration. Further, a properly grounded approach to listening will sustain government on a strategic policy course.

Setting aside that this description of a more populist approach was, itself, written in decidedly non-populist language, the spirit appears true.

Too often, though, these “new ways to obtain input from citizens and the community” are conducted, as Manning outlined, in a “source-oriented” way: “they say what they want to say, in the language they want to say it, with the media that they are most comfortable with.”

What results is either “we must remain mindful of the continued volatility in the global economy”-style gobbledegook.

Or neo-populist videos that have all the appearances of being plainspoken but that are, in fact, written in tone-deaf marketingspeak:

We’re the one thing that, despite our size, gives us a leg up: call it scrappy, call it persistent, we call it mighty. It’s the kind of might that makes us an Island of dreamers and doers; it’s guided us from the beginning, with a will and a belief that we can do anything.

To be clear: I’m not speaking about policy here. I’m neither seeking to praise Trump’s administration nor to condemn MacLauchlan’s. I’m not talking about the ideas behind their speech and their approach; my praise and criticism is about style, medium, language, spirit and tone.

The danger in all of this for Prince Edward Island is that we will, eventually, see a leader with a combination of populism, credibility, and crazy ideas, who will lead us, despite our better judgement, into dangerous waters; perhaps all that’s prevented this from happening, to this point, is the absence of a skilled-enough actor, and long-term habituation to the gobbledegook.

Of course it need not tilt that way: it’s possible that we’ll see the emergence of a populist leader, with credibility and laudable ideas, who will guide us in an entirely more positive way.

Whichever way things go, we ignore Manning’s wise words at our peril.

CBC reporter Rosemary Barton mentioned, at the recent forum on the future of news here in Charlottetown, that she’s started to read Breitbart and similar sources:

After American election, Barton realized she wasn’t reading any of the media sites that people who liked Donald Trump were reading.

“That’s a problem. That’s a problem for me, because then it means that my lens on what was happening was limited.”

So she started following the far-right American news, opinion and commentary website Breitbart, and other “further right” letters and papers.

I’ve found that it’s far more useful, and challenging, to read views that are less out of phase with my own, views that strike me not as crazy, but rather at, or just over, the edge of what my progressive social group would consider acceptable.

Quillette, from Australia, is a one such source. Its tag line is “a platform for free thought,” and the themes of its collected essays often run contrary to Canadian-style progressive canon law.

See You Are Not Important: Defund Identity Culture, for example:

Narcissistic philistinism is a condition of today’s identity culture. If one ceases to believe in the existence of profound truths, sublime terror, Art, gods, muses or geniuses (defined classically as inhuman spirits), then one’s self or identity acquires a hyperbolic sense of importance. Contrary to what is often said in Cultural Studies departments, art’s supreme function is not the expression of a middle-class self or the construction of a millennial identity; it is the forgetting of the self. In ancient Greece, Dionysus’s followers lost themselves through music; today, Selena Gomez’s followers find themselves. This does not count as progress.

Quillette makes me think, and forces me to examine my assumptions and my biases. Sometimes it strengthens them, sometimes it causes me to consider setting them aside. Isn’t that what good writing is supposed to do?

Matt Blumberg, writing about expense reports, points out a universal truth:

Most of the work we do involves some level of being organized, being on time, prioritizing work and working efficiently, and caring about money (whether the company’s money or our own money).

When I think back to work situations that have gone sideways, it’s seldom had anything to do with specific job skills and, more often than not, has been a result of someone on the team having deficiencies in one of the above.

People who don’t show up on time for meetings. Or are late all the time. Or who leave email festering in their inboxes unanswered. Or who can’t see the forest for the trees. Or who think their organizational system should trump the group’s long-established one.

When you read help-wanted ad references to “motivated” and “high energy” it’s a coded reference to these skills. Here, for example, is a snippet from the first ad that showed up in a Google search for jobs this morning:

Core competencies: customer focus communication team work quality orientation problem solving accountability and dependability operating equipment ethics and integrity

Boiled down, these amount to “you are not an idiot” and they are also another way of saying that you care about “being organized, being on time, prioritizing work and working efficiently, and caring about money.”

The reason that I am a one-person company is largely because I have almost no ability to intuit these skills in others (hiring brother Johnny allowed me to route around this; I knew he was a stand up guy because I was around for his early years).

It’s easy to spot the carnage after hiring someone without these fundamentals; it’s much more difficult to spot people without them during a hiring process. At least for me.

While we are on the topic of the Rukavina family crushing it in the digital media space, I would be remiss if I didn’t remind you that Oliver has a blog.

For a long time that was a Tumblog, but we migrated it over to Drupal earlier this year, and his posting frequency has taken an uptick since. So now he’s crushing it open source.

It’s been fascinating for me to watch Oliver grok Drupal, the platform where I spend most of my working life: he developed immediate facility for it, and can throw up a new post about twice as fast as I can.

If you’re a node on Oliver’s broad, international social graph, you’ll know well that he often uses YouTube videos to express feelings; that too is fascinating for me to watch: it’s now in his expressive muscle memory to the point where it’s as natural for him as writing is for me.

Whenever I become cynical about how the Internet has turned into a SEO-driven remarketing capitalist hell-hole, I remind myself that it is a transformative force in Oliver’s life: it’s the place he spends most of his time, his gateway to a worldwide network of friends and ideas, and a powerful tool through which he can make his mark on the world.

Follow along.

My brother Steve is hosting a new podcast for the CBC called Montrealpolis, “inside the spaces of people making modern Montreal.”

The podcast launches on Monday, April 3, and you can listen to a trailer right now.

From Steve’s introduction:

Montreal, the Canadian city with the most potholes, the thickest construction zones, and the latest last call. Whether you’re born here, or you flocked here, you’re probably staying for Montreal’s rich soundtrack of complementary languages, its lifestyle, flair, what some would call it’s perfectly dysfunctional charm. I’m trying to figure out what exactly that is.

Heretofore our access to reporter-Steve from here on Prince Edward Island has been limited to times when something of so much national import strikes Montreal that he shows up on the national news talking about it; it will be nice to have brother-on-demand-audio for a change. It will feel so Ledwellian.

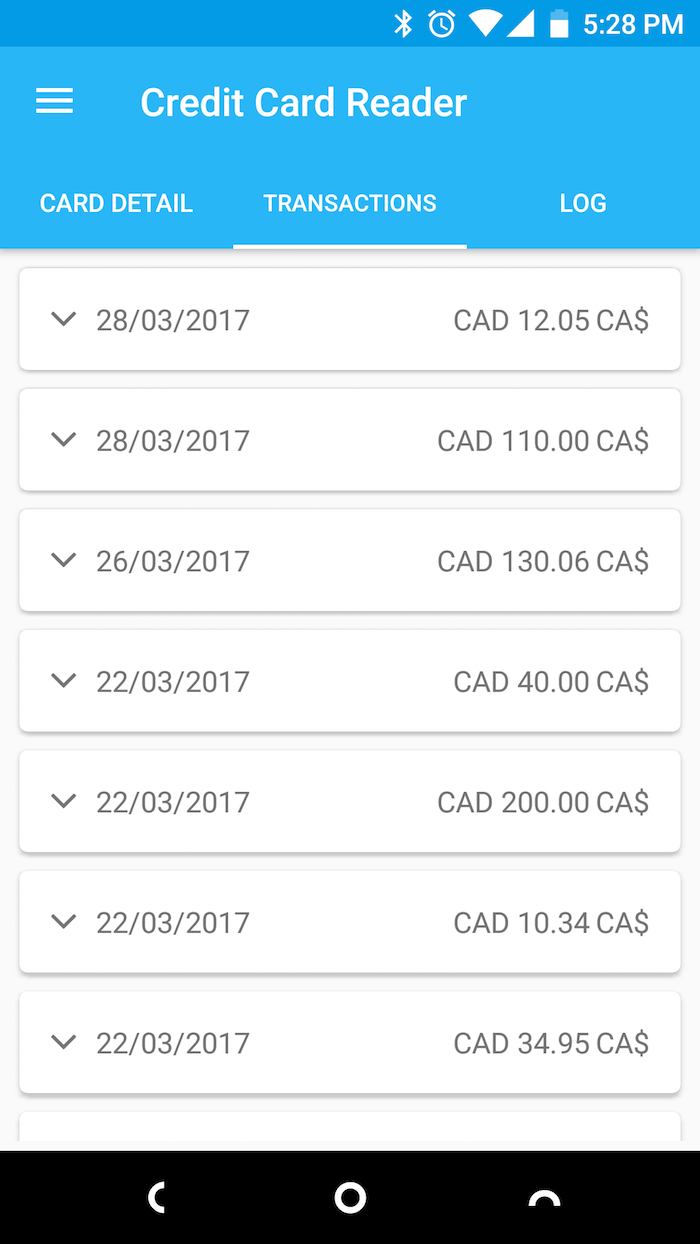

My Nextbit Robin Android phone has NFC capabilities; for practical purposes, this means that it can, with supporting software, do for me what Apple Pay can do for an iPhone. It also means, though, that it can read the contents of other NFC devices, and it turns out that credit cards themselves, at least those with “contactless” support, fall into that category.

To explore this, I installed the Credit Card Reader NFC (EMV) app on my phone, and held my MasterCard up underneath it to be scanned.

As expected, the phone was able to read the credit card number; to my surprise, however, it also read the last nine transactions processed with the card:

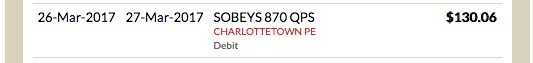

So, for example, that transaction for $130.06 on March 26, 2017 is when I did the weekly grocery shop at Sobeys; it shows up on my credit card transaction report like this:

The standard that drives all of this is, I’ve learned today, called EMV:

EMV is a technical standard for smart payment cards and for payment terminals and automated teller machines that can accept them. EMV cards are smart cards (also called chip cards or IC cards) that store their data on integrated circuits in addition to magnetic stripes (for backward compatibility). These include cards that must be physically inserted (or “dipped”) into a reader and contactless cards that can be read over a short distance using radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology. Payment cards that comply with the EMV standard are often called Chip and PIN or Chip and Signature cards, depending on the authentication methods employed by the card issuer.

Because I can read my transaction history from my card, anyone can read the transaction history from my card. This means that if we’re beside each other in the coffee line, you can, if you can get your card-reading-device close enough to my card, read my transaction history. It also means that every time I pay with my card, the merchant I’m paying can read my transaction history.

While this stored transaction information doesn’t appear to include anything about the merchant, there’s a lot that can be derived from my last 10 transactions. Look at mine, for example: from just those 7 transactions you can see, you can tell how often I use my card, how much I tend to charge to the card, and what countries I’ve visited (because the currency is recorded along with the amount). If I was a merchant processing hundreds of thousands of cards per day, I could skim all of this data, aggregate it, and start to develop fingerprints that would demographically tag card presenters based on their history.

As far as I can tell, there’s no way to turn this “feature” off on your card; I’m hunting for my MasterCard privacy statement to see whether it’s existence is mentioned there.

In a bizarre turn of events, I was able to increase the bandwidth of our home Internet from 20/2 to 100/10 by paying $2.95 more per month.

We’ve had Eastlink Internet here for a long time; so long, it seems, that our account type—”Edge” with 20 Mbps down and 2 Mbps up for $82.95/month—was “grandfathered.”

By paying the $2.95 more per month, we get ungrandfathered and move up to 100 down and 10 up, with no equipment change.

There was some suggestion from technical support that to do so would require using Eastlink’s wifi, but that doesn’t appear to be the case: all I needed to do was switch our AirPort Extreme from “DHCP and NAT” to “bridge” mode.

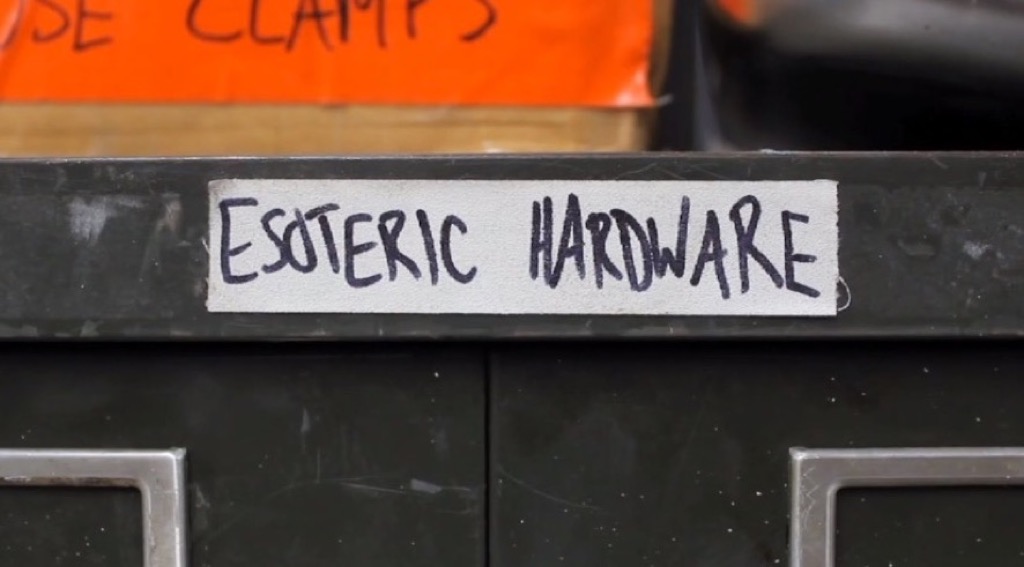

I have long been more that a little obsessed with the video Ten Bullets, from Tom Sachs. It’s a manifesto of sorts, and I live on the edge of believing in its points devotedly and feeling like it describes a sort of proto-fascist creativity prison of which I want no part.

More often than not, what wins me over to the dark side is the vigorous labeling. Of everything. In a consistent and compelling style.

The Tom Sachs approach to labeling is echoed by Casey Neistat, once a Sachs acolyte. Neistat’s studio is similarly adorned with labels:

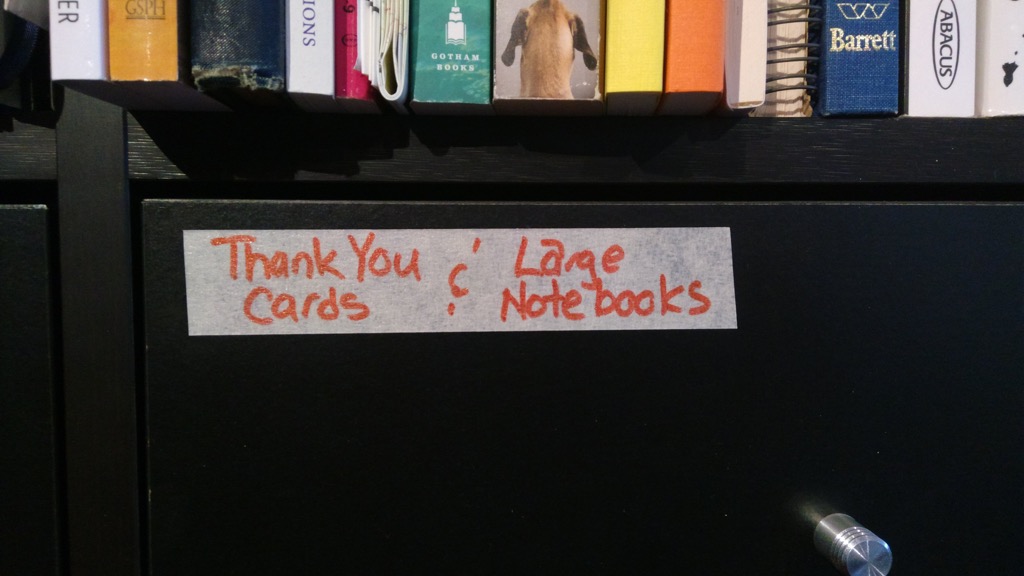

One of the things I’ve learned from studying Sachs’s and Neistat’s studios is the importance of a low-barrier-to-entry for the labeling system. Their labels are simple “marker on holder,” without much heed paid to neatness or even spelling. A chaotically-labeled something trumps a non-labeled something every time.

Where I’ve gone wrong to this point is obsessing about neatness: my labeling system has depended on a Dymo label-making-machine that I purchased about a decade ago. It produces fine labels, but it has several shortcomings:

- It runs on batteries. The batteries die. Then I forget whether I have batteries or not (yes, this is a recursive labeling issue).

- It needs special Dymo-brand tape. I can never remember where I put the cartridges. And I’m always afraid I’ll use them up. And then where will I buy more?

- The label maker has a confusing user interface, with a non-standard keyboard. Every single time I use it I have to relearned this system.

- Once the machine spits out the labels, it’s difficult to peel the backing tape from the sticky label, to the point where I hate doing this. There was, if memory serves, a tiny tool included with the machine to make this easier, but it was quickly lost.

All of the above combine to render what should be a fine label-making system instead one full of friction: in the brief window of opportunity where my mind turns to “should I stick a label on this,” my mind quickly returns “no, that will be a pain in the ass and I’ll do it later.” In other words, never.

So, inspired by the Sachs-Neistat approach, I’ve decided to scale back on the pretty-and-neat requirement, and just go with masking tape and Sharpie, which I always have right at hand, and which don’t require batteries or function keys or tricky peeling. And so witness:

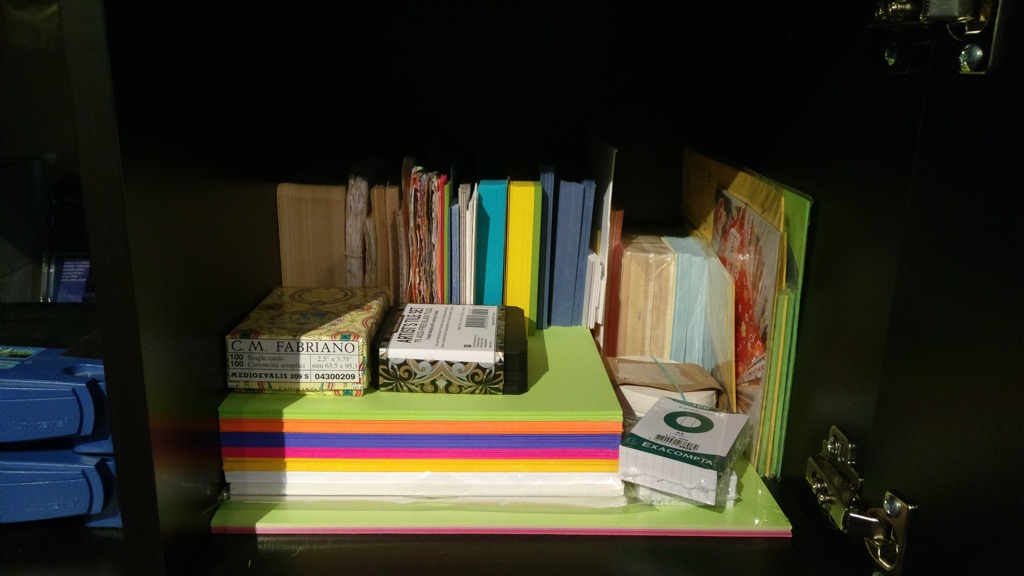

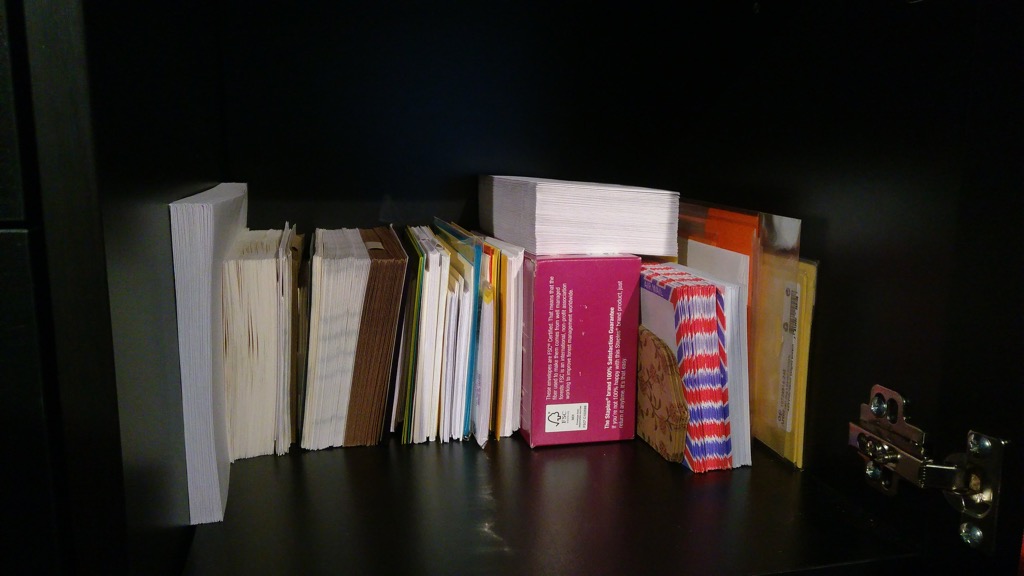

In the drawer behind that label you will find, as promised by the label, my larger notebooks (those that you won’t find on the notebook shelf nearby) and thank you cards and envelopes:

Thank you cards are important. Important enough that I printed up some custom ones, on yellow, on the letterpress. But I kept putting them in different places–places that, at the time, spoke “you will remember they are here,” but never did. And so I was forever reaching for a thank you card and not finding one and getting frustrated. Now they have a place of their own.

There’s a similar label for “Paper,” which has its own cabinet:

And for “Envelopes and Stamps” (the envelopes inside, the stamps taped to the door for easy access):

Studio organization is an ongoing process: entropy is always the wolf at the door. I’m slowly moving evermore toward perfection though.

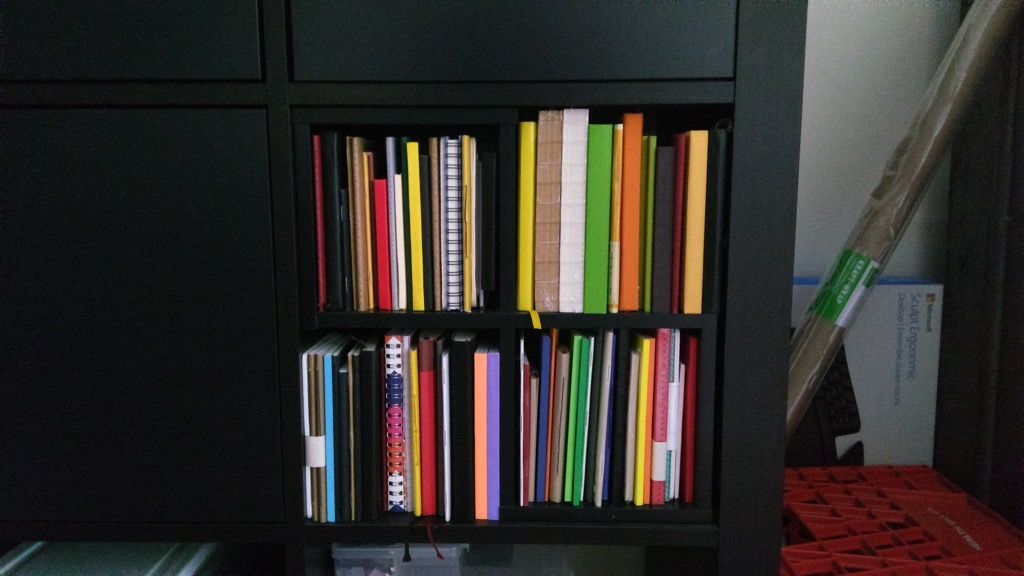

My quantum leap today, besides the masking tape approach, was to take all of my smaller notebooks out of drawers where they were hidden away from view and find a new place for them, putting them all easily at hand:

Not only are they easily at hand, but they make a work of art in aggregate to boot.

I’ve been using the Brave web browser on my desktop and on my Android phone for many months now. Especially on the phone, it can’t be beat for speed and lack of annoying “you’ve now seen 10/10 articles this month” intermediation.

While Brave’s a snappy and well-designed browser, its killer feature is Brave Payments, a Bitcoin-driven way for users to put money into a kitty, and for publishers to get compensated from the collective kitty based on aggregate usage of their site by Brave users.

I’ve thrown money into the kitty (by sending Bitcoin through Brave’s Preferences > Payments screen), but until today I never saw the publisher side of the coin.

That’s because Brave’s description of how the system works appears to suggest that you need to pass a threshold of $100 USD in payments before they’ll set you up:

These funds grow as new micropayments are added. When contributions for a publisher exceed $100.00 USD, an email is sent to both the webmaster of the site and the registered domain owner from your WHOIS information. The email explains how to verify the ownership of your website with Brave Software.

I figured it was unlikely that I’d reached $100 in payments, or, indeed, that I ever would, so I left this thought aside.

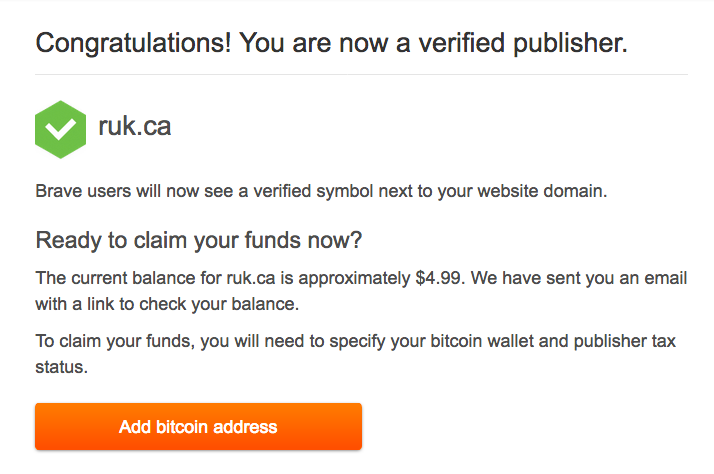

But today I noticed that right under that paragraph is a link to Get Verified Now, and when I followed that link I was able to establish ownership of ruk.ca (through adding a DNS TXT record) and, presto, I found $4.99 waiting for me:

Not enough to quit my day job, I admit, but I’ll soon have $4.99 in hand, as I followed on, entered my Bitcoin address, and filled out an IRS W-9 form (easy to do online; just needed my name, address and SSN). My funds are due to be transferred from Brave at month’s end.

I’m fascinated by the system that Brave has built, and will be watching it closely.

I am

I am