Friend of the blog Martin Rutte let me know about Moe’s Latte, a new coffee shop around the corner from us on Kent Street. It’s a Lilliputian place, with half a dozen stools, serving coffee and pastries, along with some savoury things. The vibe is chill, with a Phoebe Bridgers-forward soundtrack on the PA.

It’s nice to know there is still entrepreneurial energy in the Charlottetown coffee scene, and it’s nice to see low road spaces in downtown-adjacent Charlottetown filling out.

The front counter turns out to be an excellent place to sketch Central Christian Church across the street, which turns out to be architecturally more interesting than I’d ever paid attention to:

My friend Dave tells the great story of how he started at the CBC. He begins:

Have I told you the story of how I got into CBC? It’s ridiculous.

I was a CBC Radio listener in my late teens and early 20s. In June of 2000, I was listening to our local morning show host … introduce a contest they were running for Canada Day. He asked listeners to write a parody of a famous Canadian song. The best would win two first class train tickets to Ottawa for Canada Day, VIP passes to all the shows on Parliament Hill, and three nights stay at a hotel downtown.

Like many great “how I ended up” stories, it’s a topsy-turvy path of bravery, skill, and creating the necessary preconditions for luck.

I’ve had a similar journey.

If my mother’s college friend Heather hadn’t mentioned to me that a Victoria College professor was looking for volunteers to help enter Greek texts into a database?

If my high school biology teacher hadn’t taken us on a field trip to the Vertebrate Palaeontology lab at the Royal Ontario Museum, where they happened to need a FORTRAN programmer?

If my former Trent University professor hadn’t given me an office with a terminal that let me use the World Wide Web months after it was released?

If I hadn’t come across a copy of The Guardian in a Toronto library and found an ad for a job on PEI?

Every twisty turn was a doorway.

Every twisty turn involved help from others, enormous privilege, luck.

(My own story of “getting into the CBC”: through Marg Meikle, I met Ann Thurlow. Ann took care of the rest.)

Many years ago, I met Igor Schwarzmann in Copenhagen. We were both staying at a CABINN hotel while attending the reboot conference, and, one late night we both ended up in the lounge and struck up a conversation. We’ve been friends ever since.

Igor’s one of the most interesting people I know: a deep thinker, a trend-spotter, a deep-diver. His friend and sometimes-collaborator Johannes Kleske has similar qualities, and recently their collaboration has taken the form of a podcast, Follow the Rabbit:

We’re Igor and Johannes, two endlessly curious minds who’ve built our careers on exploring the ever-shifting landscape of culture. Join us as we work with the garage door up, sharing not just our findings, but our entire journey of discovery. Whether you’re a curious mind, a fellow researcher, or a potential client, Follow the Rabbit offers a unique glimpse into how we map, frame, and engage with culture.

Inasmuch as I’m also “endlessly curious,” and share an interest canvas with significant overlap to theirs, I’m a frequent listener.

Take this week’s Indie Magazines: From productive nostalgia to cultural anchors, where they dive into the world of print publishing, especially in the Monocle and Monocle-adjacent spaces. In part:

There is a small anecdote that I need to tell you about Monocle and their events, because when we were both, last year in London, and because Johannes is a Monocle patron, we attended a Monocle event about… What was it? Yachts and private jets?

It was private jets, mostly private jets.

And the event started with the question, do you get first a yacht or first a private jet? Which I felt like this talks to my soul. And the reason why I’m mentioning this is that you can see also there is a certain style that Monocle cultivated over a long period of time.

And they are doing it so well. And I think very few organizations are able to be so consistent across time, it makes them so recognizable and so relatable.

What I love about that isn’t that Igor and Johannes are of the jet-or-yacht class, but that they are curious about those that are. And about the house journals of those that are. (I am not immune to this Monocle-affinity: I’ve been reading since issue one).

Similarly worthy of a listen, Monthly Rewind: Luxury Markets, ADHD Soundscapes, and Conversations as Culture. What’s not to like about a wide-ranging conversation about Ozempic, trendy LA grocery stores, and an app that adjusts a soundscape to your location, activity, and mood.

(It was Johannes who originally turned me on to Readwise, an app I’ve spent hundreds of hours inside since, so I trust his futurecasting).

Listening to the podcast, I’m reminded why I love Berlin, and how long it’s been since I was there.

Last week, with great fanfare, I announced that I’d switched from using MailChimp to using Buttondown to power the ability to subscribe to a daily digest of my blog posts by email.

A week later, Buttondown suffered a technical meltdown, something that resulted in some of my 94 subscribers receiving 8 copies of that day’s email, and some—like me—not receiving it at all.

Needless to say, I was pissed off and frustrated, all the more so when the reply I received from Buttondown support was disappointingly “we’ll get back to you about this, but don’t hold your breath”:

Thank you for raising this issue about the duplicate emails going out. I have filed your experience on the Buttondown Roadmap page to be investigated and addressed. I have also associated your message to support with the ticket so that when it is resolved we can reach out directly to update you.

I was frustrated enough that I started to look elsewhere for alternative providers, to the point where I got pretty deep into setting up Moosend, a process that involved its own frustrations and limitations.

Today, before continuing down this road, I thought to look and see if Buttondown has a status page. It does. And on that page I read a very detailed blow-by-blow about what had happened, in part:

Bad configuration on one of our self-hosted SMTP servers caused a crash that proved difficult to recover from, leaving lots of emails “stuck” in varying degrees – and their being stuck manifested in a slew of unpleasant ways. We’ve fixed the configuration, are investing (literally, right at this very moment) in better tooling and alerting, and are architecting a way to prevent this from ever happening again.

and then, later on, in more detail:

Over the course of the afternoon, approximately 13,000 subscribers across 40 authors experienced some combination of the following:

- Multiple hour delays before receiving a message

- Not receiving an email at all (though we’ve redriven these.)

- Multiple sends of the same email

And that’s the fate that befell my subscribers and me.

Having managed servers professionally for more than 30 years, I am no stranger to confounding cascading technical meltdowns: some of my most challenging and frustrating hours have been spent in the wee hours, trying to diagnose some combination of web and database servers being overwhelmed. I was religious about telling my clients, when this sort of thing happened, exactly what happened and why; I treated that responsibility as seriously as my responsibility to actually fix the problem.

As I wrote last week:

I’d been reading the blog of Buttondown’s founder for awhile, and liked the cut of his jib.

Posts like this, with a photo of his office, and his bicycle, remind me that he’s a person like me, and he’s likely had a really shitty week.

This all combines to me unusually sympathetic to the Buttondown’s plight, and so I’m going to stick with them.

IKEA offers a service whereby you can have online order shipped to a central warehouse on PEI, the advantage being that it’s cheaper than having things shipped directly to your door.

We were in Halifax in March, bought a BILLY bookcase, and then realized there was no way to fit it into the car, so we returned it, and had it shipped.

(Delivery directly to our house would have been $99; shipping to the warehouse was $49.)

BILLY arrived this week.

It turns out that the IKEA warehouse on PEI is located in the Rush Transfer warehouse, on the Mason Road in Stratford. If the number of parcels in the warehouse when I went to pick up our bookcases, any indication, Islanders are ordering a lot of things from IKEA.

In a CBC story about ferry service returning for the season, I noticed this brief mention of a new event:

To welcome it to eastern P.E.I., the Northumberland will be open to the general public on April 26 and 27 as part of Doors Open Down East event.

I went looking for more information about this event—anything behind-the-scenes is my jam—and it proved hard to come by outside of social media, so I grabbed the map that’s promoting it:

There would have been a time when I would launch off on a side-project to do a levee-style razzmatazz treatment of this data, but I don’t have it in me to go there.

But you can bet you’ll see us down east next weekend.

(Kudos to Belfast Councillor Trisha Carter who first proposed the initiative back in November).

While our crocuses emerge tentatively in mid-March, it’s not until mid-April that they achieve full brilliance. This is that time.

In another month we will have tulips. And then ferns.

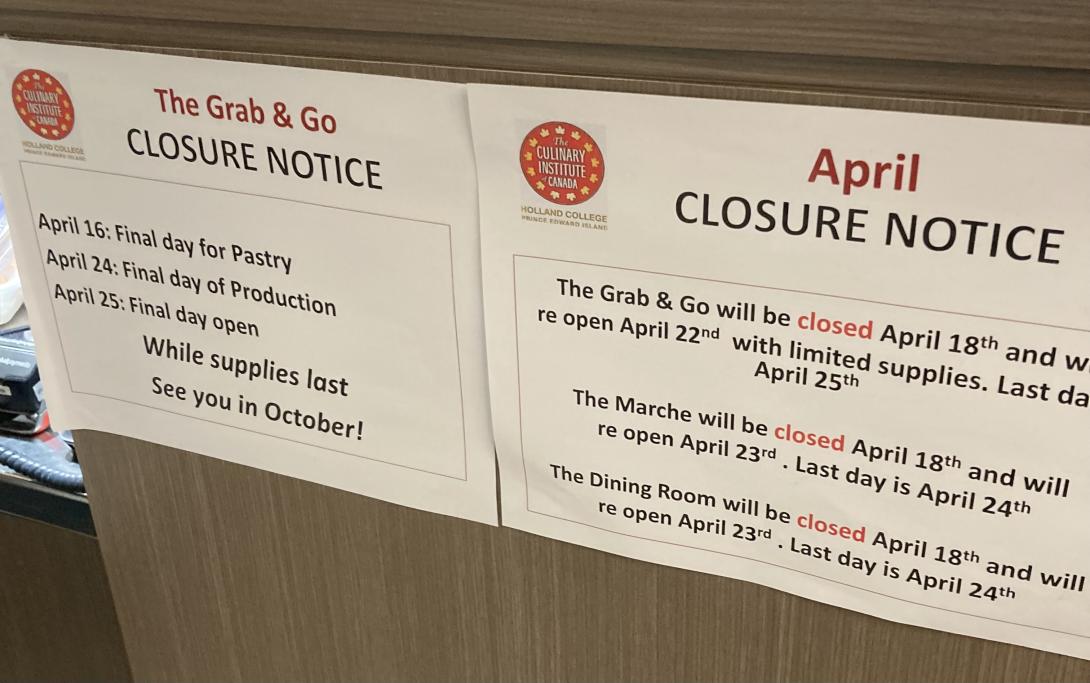

A repeating pattern in my life: one day every year, during the last few weeks of the spring semester at The Culinary Institute of Canada, I remember it offers both a great deal on lunch every weekday, and a grab & go market where they sell all manner of delights.

Yesterday was that day.

Lisa and I shared an excellent lunch, and we picked up everything from chocolates to meatballs to fresh baked bread.

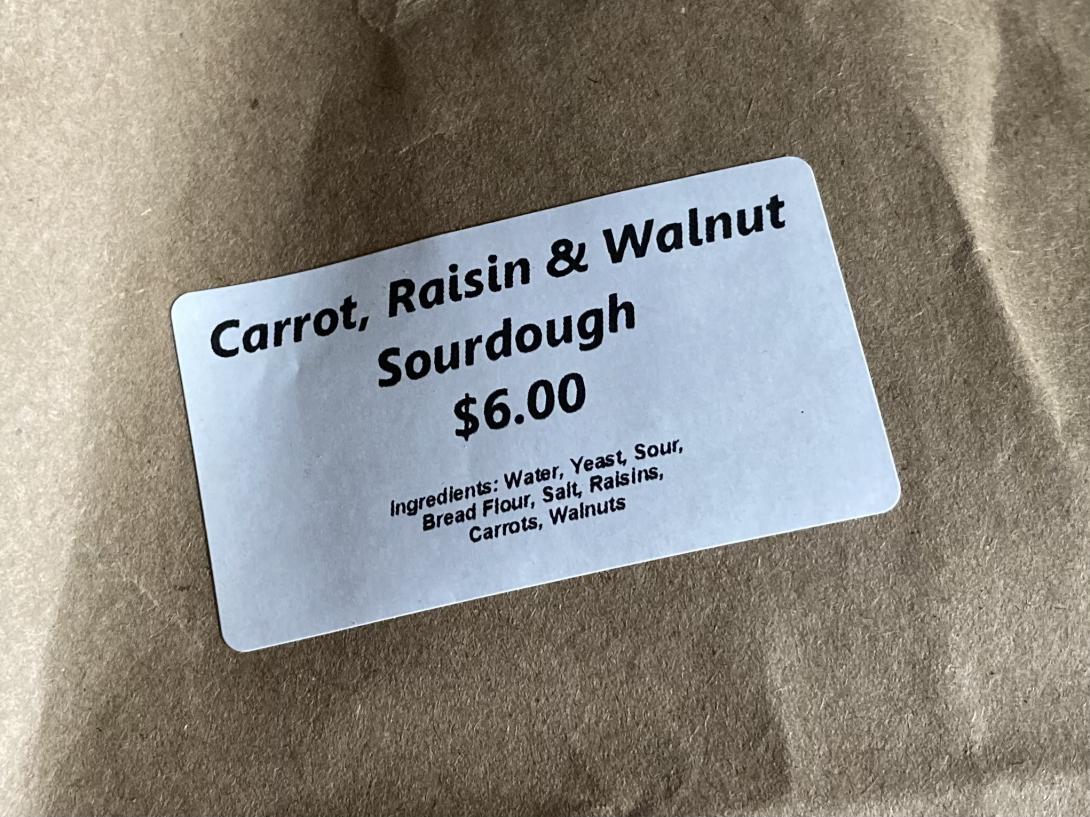

By far and away the tastiest thing we purchased was a loaf of Carrot, Raisin, & Walnut Sourdough bread. It is truly amazing.

The problem now is that the semester draws to a close next week, and neither lunch nor market returns until October. To deal with this, I’m going to put a reminder in my calendar for October, with hopes that I’ll be able to enjoy both more than just one week a year.

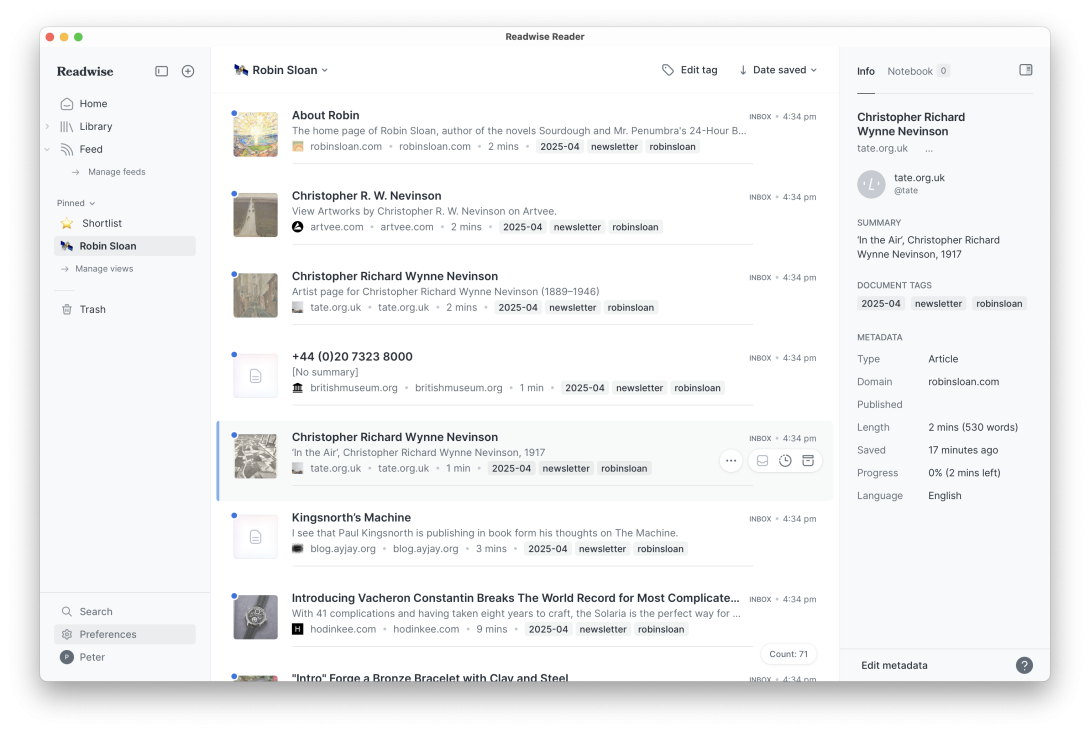

The Venn of “links in Robin Sloan’s email newsletters” and “things that interest me” is incredibly high. I noticed this especially with the April Edition: I read the newsletter in Readwise Reader, and I was adding almost every link to the queue for reading later in Reader.

So I decided that I needed a Robin Sloan Machine: a bit of code that would take all the links in the public URL for the newsletter and add them to Reader for later reading.

My ask to ChatGPT:

I have a URL that I want to extract all the links from, and then feed each link to the Readwise Reader API, adding each URL, with title, and tags of my choosing, as Readwise items. Please provide me with a PHP script that will do that. Make the original URL an argument for the script, and make the tag(s) an argument to the script, so that I can pass these as parameters and feed other URLs in a similar way.

The first pass at this was fully functional. I tinkered a little in subsequent prompts.

Anticipating that I might want to call this as an API endpoint on my own server at some point:

Please modify the PHP script so that it will accept EITHER parameters passed on the command link, OR the URL query parameters “url” and “tags.”

Tweaking the Reader API to clean up the HTML, and realizing that my script doesn’t need to figure out the title, as Reader will do that itself:

Modify the script so that it doesn’t need to pass the “Title” parameter to the Readwise API — the API will calculate this on its own when it reads the URL. Also, add the API parameter “should_clean_html” when calling the Readwise Reader API, and set it to “true”.

And, finally:

Modify the script so that multiple links found that are different only because they have a hash tag at the end are not sent — just send ONE to Readwise. And, finally, add code to pay attention to the note in the API about rate limiting.

Here’s the final script:

<?php

$isCli = php_sapi_name() === 'cli';

if ($isCli) {

if ($argc < 3) {

echo "Usage: php index.php <source_url> <tag1,tag2,...>\n";

exit(1);

}

$sourceUrl = $argv[1];

$tagsInput = $argv[2];

} else {

if (!isset($_GET['url']) || !isset($_GET['tags'])) {

header("HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request");

echo "Missing 'url' or 'tags' query parameter.";

exit;

}

$sourceUrl = $_GET['url'];

$tagsInput = $_GET['tags'];

}

$tags = array_map('trim', explode(',', $tagsInput));

$readwiseToken = 'YOUR_READWISE_API_TOKEN'; // Replace with your actual token

function fetchHtml($url) {

$context = stream_context_create([

'http' => ['header' => "User-Agent: PHP script\r\n"]

]);

return @file_get_contents($url, false, $context);

}

function normalizeUrl($url) {

$parsed = parse_url($url);

if (!$parsed) return $url;

// Remove fragment

unset($parsed['fragment']);

// Rebuild URL without fragment

$normalized = '';

if (isset($parsed['scheme'])) $normalized .= $parsed['scheme'] . '://';

if (isset($parsed['user'])) {

$normalized .= $parsed['user'];

if (isset($parsed['pass'])) $normalized .= ':' . $parsed['pass'];

$normalized .= '@';

}

if (isset($parsed['host'])) $normalized .= $parsed['host'];

if (isset($parsed['port'])) $normalized .= ':' . $parsed['port'];

if (isset($parsed['path'])) $normalized .= $parsed['path'];

if (isset($parsed['query'])) $normalized .= '?' . $parsed['query'];

return $normalized;

}

function extractLinks($html, $baseUrl) {

libxml_use_internal_errors(true);

$dom = new DOMDocument;

$dom->loadHTML($html);

$xpath = new DOMXPath($dom);

$links = [];

foreach ($xpath->query('//a[@href]') as $node) {

$href = trim($node->getAttribute('href'));

if (!$href || strpos($href, 'javascript:') === 0) continue;

// Convert to absolute URL if needed

if (parse_url($href, PHP_URL_SCHEME) === null) {

$href = rtrim($baseUrl, '/') . '/' . ltrim($href, '/');

}

$normalized = normalizeUrl($href);

$links[$normalized] = true; // use keys for uniqueness

}

return array_keys($links);

}

function sendToReadwise($url, $tags, $token) {

$payload = [

'url' => $url,

'tags' => $tags,

'should_clean_html' => true

];

$ch = curl_init('https://readwise.io/api/v3/save/');

curl_setopt($ch, CURLOPT_RETURNTRANSFER, true);

curl_setopt($ch, CURLOPT_HEADER, true);

curl_setopt($ch, CURLOPT_HTTPHEADER, [

'Authorization: Token ' . $token,

'Content-Type: application/json'

]);

curl_setopt($ch, CURLOPT_POSTFIELDS, json_encode($payload));

$response = curl_exec($ch);

$headerSize = curl_getinfo($ch, CURLINFO_HEADER_SIZE);

$header = substr($response, 0, $headerSize);

$body = substr($response, $headerSize);

$httpCode = curl_getinfo($ch, CURLINFO_HTTP_CODE);

if (curl_errno($ch)) {

echo "cURL error for $url: " . curl_error($ch) . "\n";

} elseif ($httpCode == 429) {

echo "Rate limit hit for $url. ";

preg_match('/Retry-After: (\d+)/i', $header, $matches);

$retryAfter = isset($matches[1]) ? (int)$matches[1] : 60;

echo "Waiting for $retryAfter seconds...\n";

sleep($retryAfter);

sendToReadwise($url, $tags, $token); // Retry

} elseif ($httpCode >= 200 && $httpCode < 300) {

echo "Sent: $url\n";

} else {

echo "Failed to send $url. HTTP $httpCode\n";

echo $body . "\n";

}

curl_close($ch);

}

// MAIN

$html = fetchHtml($sourceUrl);

if (!$html) {

echo "Failed to fetch source URL: $sourceUrl\n";

exit(1);

}

$links = extractLinks($html, $sourceUrl);

echo "Found " . count($links) . " unique normalized links on $sourceUrl\n";

foreach ($links as $link) {

sendToReadwise($link, $tags, $readwiseToken);

sleep(1); // basic pacing

}I ran this on my Mac with:

php index.php https://www.robinsloan.com/newsletters/golden-sardine/ "robinsloan,newsletter,2025-04"I set it to run, and ended up with 85 new links in my Reader for browsing. I created a View in Reader to segregate them into their own handy area (tag:robinsloan):

From start to finish this took about 35 minutes to create and refine. It would have been possible without ChatGPT sitting on my shoulder whispering code in my ear, but it would have taken a lot longer.

If you have ever looked up a recipe online, you will know that the standard format that’s emerged, in this SEO-dominated world, is like this:

- Title

- Brief Description

- Hundreds of words of SEO-targeted useless drivel

- The recipe

This recipe for shrimp stir-fry, for example, has 792 words of filler material before you get to the actual recipe, filled with “content” like “What People Are Saying.”

I just want the recipe!

Somewhat helpfully, also part of the standard format is a link, sometimes subtle and near-hidden, “Jump to Recipe,” that lets you skip the fluff (because the fluff, after all, isn’t intended for humans, it’s fodder for robots).

Meanwhile, AI.

Tired of the everyday fizzy water, I asked ChatGPT:

Give me a recipe for a fresh Sodastream non-alcoholic cocktail using common kitchen ingredients.

To which it replied:

Here’s a simple, refreshing non-alcoholic cocktail you can make with a SodaStream and common kitchen ingredients. It’s got a little zing, a little sweetness, and plenty of sparkle.

Citrus-Ginger Fizz

Ingredients:

- 1/2 lemon (or lime), juiced

- 1–2 tsp honey or maple syrup (to taste)

- 1/2 tsp grated fresh ginger (or a pinch of ground ginger)

- Sparkling water from your SodaStream

- A few fresh mint leaves (optional but great)

- Ice cubes

Instructions:

- In a glass or small jug, combine the lemon juice, honey or syrup, and ginger. Stir well until the sweetener dissolves.

- Add a few mint leaves and gently muddle them with the back of a spoon (optional).

- Fill a glass with ice cubes.

- Pour the citrus-ginger mixture over the ice.

- Top with fresh SodaStream sparkling water.

- Give it a gentle stir. Taste and adjust with more honey or lemon if needed.

- Garnish with a mint sprig or a citrus wedge if you’re feeling fancy.

Sure, hallucinations, intellectual property theft, lack of sourcing–all completely valid concerns as we move toward an AI-driven Internet.

Say what you will about all that, though: I now have a machine that I can ask for a recipe and that will give me a recipe. That’s hard to resist, and makes the old “Google, wade through advertising, pick a search result and hope for the best, click Jump to Recipe” pattern seem inane.

The “Citrus Ginger Fizz,” by the way, was delightful.

I am

I am