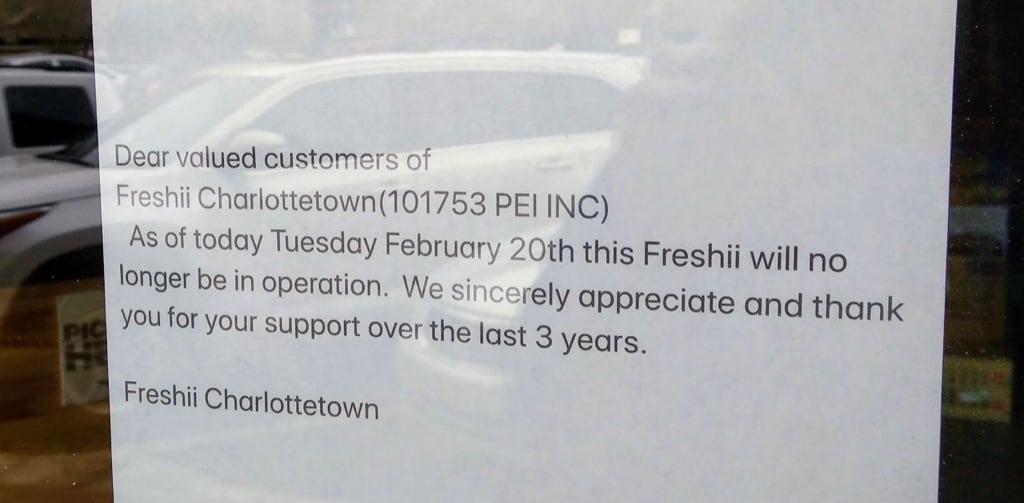

We workers of Queen Street arrived Monday morning this week to find that the Freshii location in the old Woolworth’s was closing up shop.

When Freshii first opened I was a regular customer, often getting lunch there two or three times a week: the food was, true to the name, fresh, the staff were friendly, and it was handy-by.

Over the last while, though, I soured.

From a quality and service perspective things never seemed to be the same once partner-business Dynamic Fitness moved to Pownal Street. The Freshii online ordering app, which I tried to use as an early-adopter, was an unmitigated disaster. Other places opened nearby that were more on their game.

The straws that broke the camel’s back happened at a brand level: first came the refusal to abide by Ontario’s requirement to publish calorie counts for menu items, and second was what appeared to be a doubling-down on the “juice cleanse” fad, something that is absent scientific evidence.

And so I hadn’t been into Freshii for more than a year when the news came. And so I was right: 2016 was Peak Juice Bar in Charlottetown.

The Guardian reports that the City of Charlottetown Planning Department is seeking input on any amendments to the Zoning and Development Bylaw that might be required once the retail sale of cannabis becomes legal later this year.

Here’s the input I offered:

This email is in response to reports in The Guardian that you are seeking input from the public on any amendments that might be required to the Zoning and Development Bylaw regarding the retail sale of cannabis, and, specifically, distance limitations with relation to “schools, daycares and places where children assemble.”

My input is: there is no need to any amendment to the Zoning and Development Bylaw at all.

The retail sales of cannabis should be permitted anywhere that the retail sale of anything else is permitted.

I see no conflict between the retail sales of cannabis and the presence of children, or of anyone else.

I am fascinated by how provincial and municipal politicians are riding a knife-edge of favouring legalization while feeling an obligation (or genuine feeling) to express vague discomfort about the entire notion. Former Finance Minister Albert Roach, for example, was quoted on the CBC in December discussing locations for provincial cannabis stores:

“To ensure that wherever we put them, that they are not in any sort of a co-location, next door or in the same mall as a current liquor store … We don’t want to locate near schools or playgrounds … we want to be very clear that that’s a concern to us,” he said.

I’m not sure what evils Mr. Roach, or the City of Charlottetown, might come from playground-cannabis store-proximity; it’s truly perplexing. Are they expecting gun play? Do they imagine stoned people milling about expressing dangerous, divergent thoughts?

I hope the City does the sensible thing, and simply proceeds business-as-usual.

The Government of PEI is seeking input on a proposed update to Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy legislation, with a deadline of this Friday, February 23, 2018.

Here’s the submission, sent today:

Please accept the following comments from me in response to your call for feedback in the ”Modernizing the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act” paper.

I am a longtime user of the FOIPP mechanisms afforded by the provincial and federal governments, as well as, more recently by the University of Prince Edward Island. I’m also a longtime practitioner of, and advocate for, open data use.

I have two general comments to make, focused on the intersection of open data and FOIPP legislation.

1. While the Government of PEI, in recent years, has begun to establish the technical and policy groundwork for a more open approach to data, there remains an attitude in the public service that the role of a public servant is, writ large, to act as a gatekeeper for data. This role is only reinforced by the dynamic of the access provisions of FOIPP legislation which, by carefully defining the mechanisms for access, serve to enhance the notion of the public service as guardians of a bank vault of data that is only to be parcelled out carefully, on a cost-recovery basis, in response to specific requests. A truly open and transparent approach to data would see public servants mandated to release as much data about what they do, how they do it, and how it went, as often as possible; their job performance should be judged, in part, by their success in doing so, in much the same way as academics are rewarded for the volume of their publications.

2. In a similar vein, it is at our peril that we continue to regard open data and FOIPP as in opposition. The public service, because of resource constraints, is often faced with the question of where to turn its open data efforts first: tremendous benefit would come from using access requests themselves as semaphores for public interest, and to use access requests as the trailheads of proactive disclosure. Not only would this be an effective use of resources, but it would also result in a change, on a technical level, from treating access requests as one-of technical jobs to treating them as prompts to build systems that are open-data-enabled. For example, if I submit a FOIPP request for a list of survey markers, the likely response currently would be that a technician would prepare a one-time data export of survey markers from an internal system, and I would receive this by email or on physical digital media; a more effective response, in contrast, would be to use the same resources to extend a bridge between the internal survey marker system and open data infrastructure so that the data becomes open to all as a regular course of action, without the need for additional FOIPP requests.

In addition, I have some specific responses to points you raise in your paper:

Information and Privacy Commissioner: In 2006 I submitted an access request to Health PEI for information related to financial transactions related to my personal health care. Health PEI denied my request, and I appealed to the Information and Privacy Commissioner. The adjudication of this appeal was delayed multiple times, over the course of several years, and it was not until 1007 days later, in 2014, that I received the information I’d requested. In letters from the Information and Privacy Commissioner regarding the delays it was made clear to me that the reason for the delay was simply that her office did not have the capacity to deal with its workload. As such, I believe that effective administration of the FOIPP Act requires that the Information and Privacy Commissioner’s office be sufficiently resourced to carry out its duties under the timelines laid out in the Act.

University of Prince Edward Island: The University of PEI updated its own FOIPP policy last year, and I find it problematic in two ways. First, there is a $25 non-refundable processing fee for each request, which I find onerous (especially when contrasted to the more reasonable $5 established under provincial FOIPP legislation). Second, the policy does not apply retroactively, so that information and data gathered before May 2015 is not subject to the policy. While I can appreciate that there are limited situations where this might be appropriate, I believe the starting point should include retroactivity, with only specific limitations to this. Ultimately, I believe that it would be more sensible and efficient to have the University of PEI covered by provincial FOIPP legislation.

Municipalities: As a longtime resident of the City of Charlottetown, I have found access to information and data maintained by the City to be effectively unavailable in many situations. This is particularly problematic as the City holds data that in many ways is the most relevant to the day-to-day life of citizens, data that could most effectively be used by citizens to advocate and analyze. While the Province of PEI has made progress on the “open data culture shift,” in my experience the City is still working in a “tell us why you want this data, and what you’re going to use it for” era. For example, several years ago I asked the City for a digital copy of the GIS layer for its Zoning and Development Bylaw, and this request was arbitrarily denied at a bureaucratic level (ultimately I was given a copy by a City Councillor, something no less problematic). As such, I believe strongly that the FOIPP Act should be extended to municipalities.

Fees: Pursuant to my comments above related to using access requests as a semaphore for public interest and an opportunity to build open systems, I believe that processing fees should be eliminated entirely. They are a barrier to access and, ironically, are highest for information that is, from a technical perspective, the most technically challenging to make accessible. Citizens should not be punished financially for requesting information that is, by dint of history, buried the deepest, so to speak. FOIPP requests should be looked upon as a gift from citizens to the public service, and the technical expenditure an investment in openness.

If you have thoughts about FOIPP legislation in PEI, I encourage you to submit something before the deadline at week’s end is up.

Longtime readers may recall that two years ago I wrote about the 25 subscribers to The New Yorker magazine on Prince Edward Island.

At the time I wrote:

Perhaps I can cement up the list and organize some sort of gathering for us all. We could find a big wooden table in a corner somewhere and chat for hours about William Shawn and Tina Brown and our feelings about the reordering of the front matter.

The time has come.

Next Wednesday, February 28, 2018 at 7:00 p.m. I’m organizing a little gathering of Prince Edward Island New Yorker subscribers in Charlottetown.

If you’re in that group, and you’d enjoy an informal drink with fellow New Yorker readers, please contact me for details.

Oliver and I took Ethan for a walk along the boardwalk yesterday, and I took this photo while standing in front of the Culinary Institute facing Government House. Google Photos automagically transformed it into a striking black and white photo, so I can’t claim any credit for that.

It was a day off school for Oliver today, so we walked from downtown to the Charlottetown Mall to see Black Panther. Added to the rest of our walking around today, Oliver’s Fitbit counted 11,849 steps. That’s a new record for him, since Christmas.

Such a long walk was more possible today because of the mild temperatures: it hovered around 2°C for most of the day.

A side-effect of of this was that the sidewalks and trails were very muddy: by the time we arrived at the mall Ethan the white dog was almost solid brown in places, and Oliver and I had trousers caked with mud.

We avoided a repeat performance by taking the bus home. Ethan got a bath, and our trousers went into the laundry, and things have just about returned to normal now.

Surely the brand book for Pepsi has some sort of “advertising that appears to suggest mixing gasoline with our beverages is to be avoided” guidance.

The Island’s record store, Back Alley Music, has a new home at 257 Queen Street, between Fitzroy and Euston, and the expanded space has afforded it the opportunity to welcome a vegan take-out, called Stir It Up, to its midst.

This places Charlottetown in the remarkable position of having, along with My Plum, My Duck, two vegan restaurants. Our corned-beef-and-cabbage-eating ancestors wouldn’t know what to make of the place.

I’ve been by Stir It Up for lunch a couple of times now, having the “FLT“–a vegan take on the bacon, lettuce and tomato sandwich–both times.

I’m not 100% sold on the sandwich–if their goal is to recreate the BLT faithfully in vegan form, they’ve a ways to go on issues like “lettuce crispness” and “fake bacon snappiness”–but I laud the effort. And the space, the staff and the idea of the place are enough to bring me back again.

The service is a little pokey, for which I’m willing to hand them a “good food, well-prepared takes time” get-out-of-jail-free-card. Fortunately, the environs are pleasant enough, and when you run out of energy for flipping through the vinyl record bins, there’s a comfortable mid-century modern chair to set down in, complete with a view of Stompin’ Tom.

It was a year ago today that I cleared out my Twitter archive, emitted one last Tweet, and decamped from social media altogether.

In the same way that it took me a while to kick a sugar habit, it took me a while to deprogram my brain from its Twitter-dependence. For weeks afterward I continued to think in the pithy ironic thoughts that Twitter demands, and, without an outlet, would get momentarily frustrated.

But like the jones for a Snickers, this too passed, and I’ve never looked back.

All the “oh my, I’ll have no idea what’s going on!” fears that my mind stoked up for me didn’t come to pass: I didn’t leave the Internet, after all, didn’t retire to a cabin in the woods. And Oliver is as voracious a citizen of Twitter, Instagram and Facebook as I ever was, and he keeps me in the loop on things I really need to know.

It turns out that the much-vaunted “continuous partial attention” isn’t all its cracked up to be, and I’ve discovered that the thin simulacrum of “connection” that Twitter afforded was meaningless from a practical and spiritual perspective.

I say all this not to proselytize–those still inside the matrix won’t believe anything I’m saying in any case–but simply to mark the anniversary, and to remind myself that it’s a good idea to stand up and pay attention once in a while to the habits, especially the digital ones, that are so easy to get lost in.

Meanwhile, I wrote more here in 2017 than I did in any of the eight years previous. And I started to draw. And I set and printed more. And paid more attention to those around me.

There’s a tiny “return to blogging” movement that I’m happy to see in progress (Ton, for example, and Dries) and to be a part of.

I’m into 33rd year on the Internet this year, and I continue to be fascinated by it as a medium for writing and making connections; we’re not done yet.

I am

I am