After The Day That Didn’t Go So Well, back on New Years Eve 2016, Oliver was loathe to experience the exigencies of airport security any time soon, so the last 18 months have been a sort of Dark Ages of Travel, with our adventures restricted to land-based transport.

On Saturday, however, thanks to the good graces of the Autism Society, Air Canada, Charlottetown Airport and Danny Murphy, Oliver was able to try climbing back on the airport horse to see how it felt.

And it felt pretty good, he reports.

Saturday, you see, was Autism Aviators day at the airport, an event where young people with autism could try flying on for size. Although there was no flying involved–a few moments in Danny Murphy’s private jet, on the ground, was the proxy–the rest of the proceedings were a realistic simulation of airport logistics: check-in, baggage screening, security, waiting in the departure lounge, boarding, landing, and picking up luggage.

Oliver’s an old hand at most of this; it was the security screening that he was worried about. But he remained calm. And I remained calm. And the CATSA agents remained calm. And Ethan the Dog remained calm. And we just sailed right through, unscathed.

Here’s what we looked at once we reached the departure lounge a few moments later:

Can you tell we are relieved and happy?

The day was successful enough that Oliver is, indeed, ready to climb back on the flying horse, and plans are afoot to determine how we will use this newfound freedom.

All involved in organizing this event should feel proud of their commitment to accessibility. Thank you.

Charlottetown’s buses are now equipped with GPS devices that send real time location data to a server where it can be used by the ReadyPass transit app for iOS and Android.

There’s also a web version of the map, and, by looking under the hood of it, you can see that there’s a simple public API endpoint that provides the same real time location data.

To watch this for yourself, just open the web map in your browser, and open up the developer console, switch to the Network tab, and filter for XHR requests:

![]()

What you’ll see happening there is a regular call to get the position of the buses on the route you’ve selected, in the form:

http://charlottetown.readypass.ca/api/bus/route/ROUTE

For example:

http://charlottetown.readypass.ca/api/bus/route/1

The returns a JSON object with data for all of the buses currently on that route, like this:

[

{

"busNumber":"62",

"routeNumber":"1",

"lat":46.264949798583984,

"long":-63.14606475830078,

"cellStrength":0.017,

"speed":0,

"updateTime":"2018-05-03T20:47:10.342189124Z",

"maxBump":0,

"avgBump":0,

"bumpSamples":0,

"accuracy":100,

"battery":255

},

{

"busNumber":"60",

"routeNumber":"1",

"lat":46.239139556884766,

"long":-63.13039779663086,

"cellStrength":0.007,

"speed":5.4,

"updateTime":"2018-05-03T20:47:10.401472557Z",

"maxBump":0,

"avgBump":0,

"bumpSamples":0,

"accuracy":100,

"battery":255

}

]

So that tells us that, right now, there are two buses, #62 and #60, and they are at the latitude and longitude given. Also available, it seems, is the call strength of the data connection in the bus, its battery level and the accuracy of the position.

This is great data to have access to and, as has happened in other jurisdictions, will enable the creation of useful transit information services and data visualizations.

To learn more about midwifery on Prince Edward Island, watch this excellent video produced by BORN which makes the case clearly.

BORN has been advocating for the re-introduction of midwifery to the Island for years and years and years. It appears now that we may be on the cusp of success, as discussion in the Legislative Assembly this week suggests that the required legislation may be in place this summer.

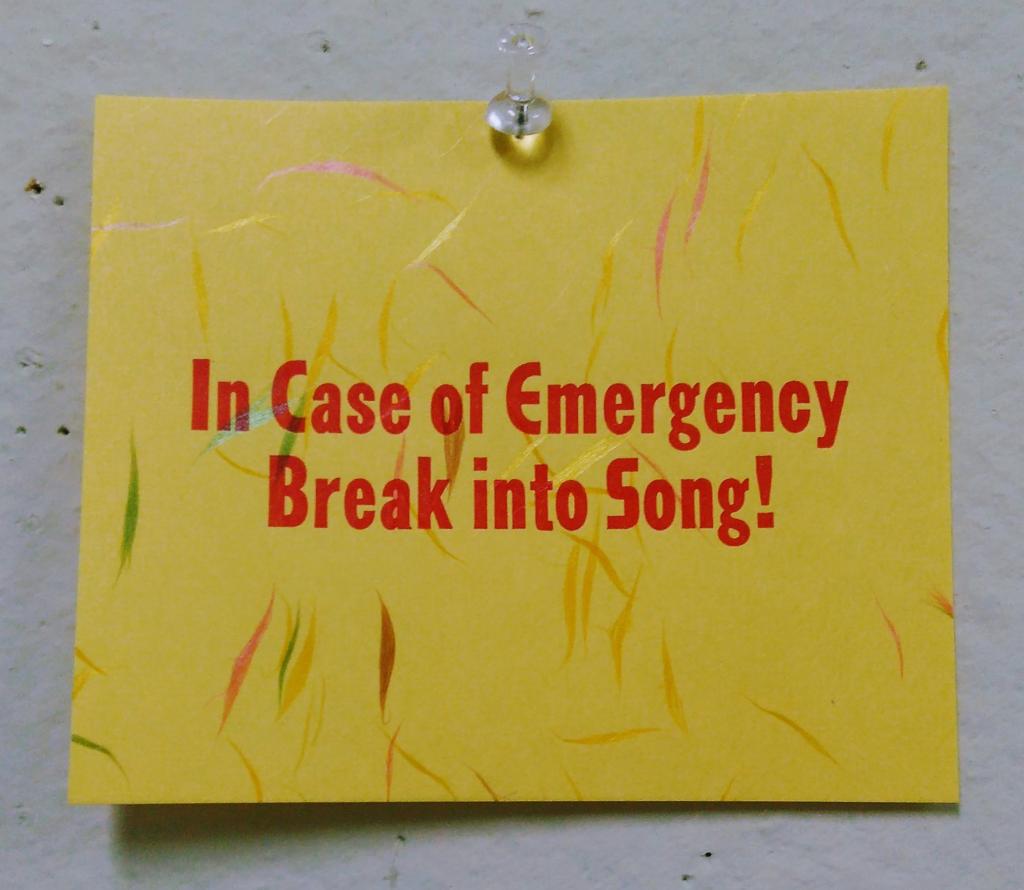

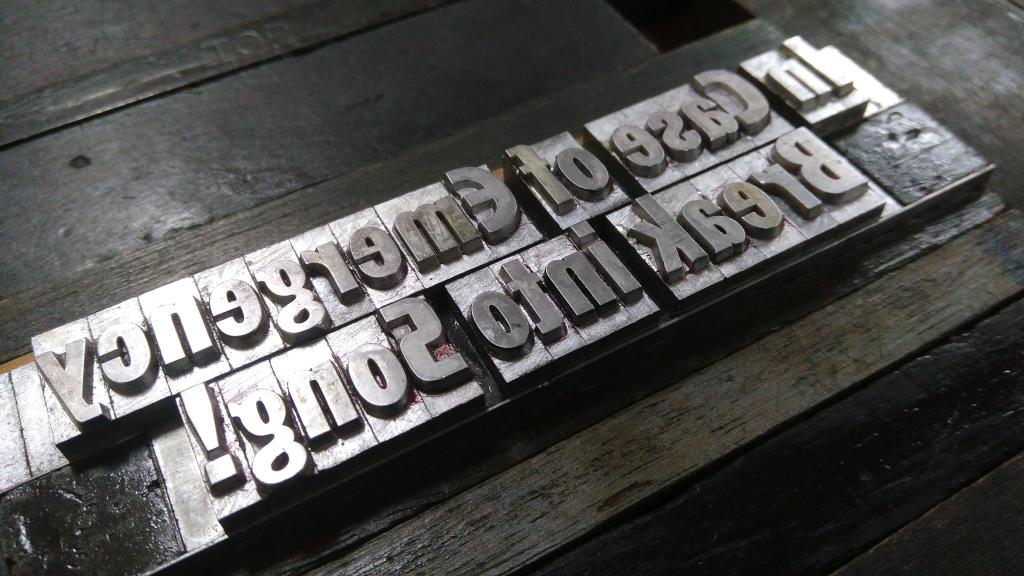

I conjured these up today, inspired by memories of life inside The Guild at this time of year, with Anne and Gilbert entering rehearsal and song filling the halls. My new office is near-silent, at least when the violin teacher next door isn’t teaching, but these remain solid words to live by.

The typeface is 36 pt. Tourist Gothic, acquired from Letterpress Things three years ago. It’s got some funky alternate capitals, and I used the alternate E and the S here; I love them for their weirdness.

The paper is from an inexpensive pad of Japanese note paper that I bought in Toronto for $4 a couple of years ago.

The ink is an old can of Flame Red that Kwik Kopy kindly donated to me.

It was a fine day for printing, with almost perfect humidity; things rolled out seamlessly.

,

,  ,

,

A friend recommended Grant Matheson’s book The Golden Boy to me a few weeks ago. All of the copies at the public library were on hold, so I purchased a copy from Amazon for the Kindle, and read it, in one sitting, on the tiny screen of my phone.

It’s a gripping tale, well-told, of personal tragedy and personal triumph: I learned a tremendous amount about addictions and treatment and recovery that I didn’t know; perhaps most prominently, that addiction doesn’t discriminate, and can affect anyone, of any stature or income or life situation.

The greatest lesson from the book, however, is that it demonstrates the redemptive power of what I’ve long-termed “the obligation to explain.” Matheson took his personal story, which otherwise would have remained the stuff of rumour and innuendo, and laid it bare for all to read about, and to learn from. In doing so, he’s provided a valuable gift to us all, and one that might end up changing more lives for the better than he ever would have as a family doctor.

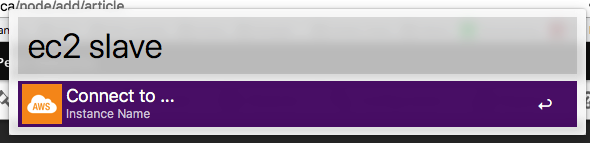

I’ve been a longtime user of the excellent Elastics utility for the Mac for managing connections to Amazon Web Services EC2 instances: it provides a handy menu bar item with a drop-down list of running instances, with a link to connect to each via SSH.

Unfortunately Elastics has been slowly dying on the vine with each new version of Mac OS, and with recent updates to High Sierra it’s stopped working completely for me so I needed a replacement. While there have been various attempts to build alternative “manage your AWS instances in a GUI” utilities, none has the elegance of Elastics, and many of the features are overkill for me: all I really need is a quick way of SSHing to an instance by instance name.

Here’s what I built.

First, I made a shell script call aws-connect.sh that looks like this:

#!/bin/sh

aws ec2 describe-instances --filters "Name=tag:Name,Values=$1" --query "Reservations[0].Instances[0].PublicDnsName"

It uses the AWS command line utility aws to return the public DNS name of the instance I pass it on the command line. So if I do:

./aws-connect.sh slave

it will return the public DNS of an instance I’ve named “slave,” like this:

"ec2-164-71-182-18.compute-1.amazonaws.com"

I then created a workflow, another shell script, in Alfred that looks like this:

export EC2HOST=`~/bin/aws-connect.sh {query} | tr -d '"'`

ssh -t -p 22 -i 'keypair.pem' ec2-user@$EC2HOST

This script puts the public DNS of the named instance (passed from Alfred as {query}), with the quotes stripped out, into the EC2HOST shell variable, and then SSHes to that instance using my AWS keypair.

When this is all glued together, connecting to an AWS instance, assuming I know the name, is as simple as invoking Alfred (with Control + Space in my setup) and typing ec2 [instance name]: a Terminal window opens, and I’m connected to the instance. It doesn’t replace everything that I used Elastics for, but it does replace the most important thing, and that’s a big help.

From our eagle-eyed brother on the ground in Montreal, a pointer to Improbable Habitat - Montréal vs, an exhibition on display in a park in Mont-Royal. The Google-translated description:

Begun in the fall of 2013, following a trip to Paris, the series Improbable Habitat is a project that is enriched over the years by new paintings. It explores the contrasts created by the connection of typical dwellings of different cities to that of Montreal.

As Charlottetown is a major world capital, it’s one of the cities experimented with, imagining a typical Montreal duplex transplanted into Bayfield Street, and vice-versa.

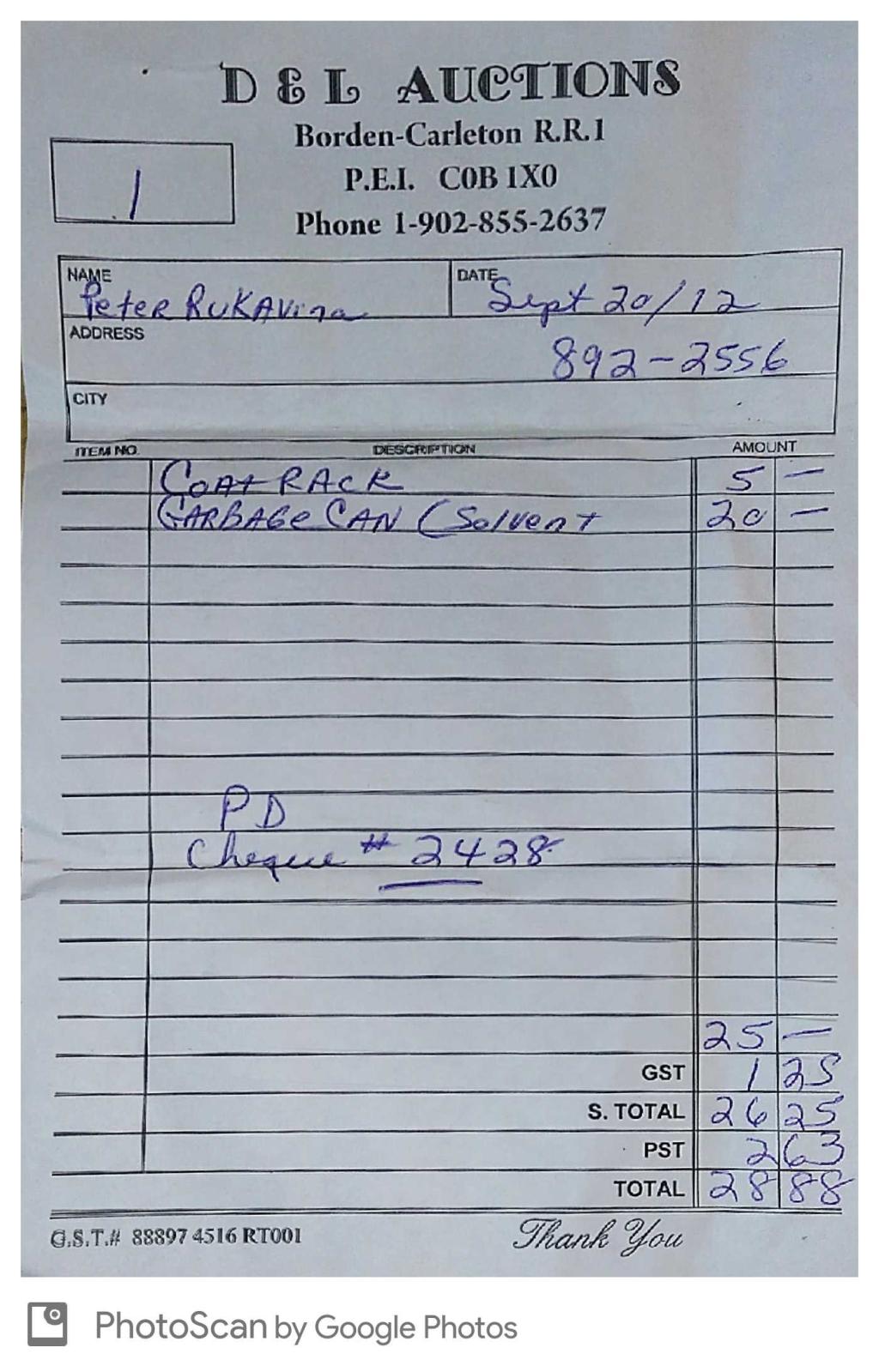

I purchased this coat rack in 2012 when the Queen’s Printer held an auction upon getting out of the business of printing.

When I purchased it, for $5, the legs were held together with duct tape and thus my coats were always in danger of plummeting to the ground.

On moving into the new office, I decided to address this, and dropped the coat rack at McAskill’s to be repaired. A couple of weeks and $60 later, it’s as good as new.

,

,

I finally took the calendar type I purchased in 2016 from The Printing Museum in New Zealand out of its box and used it to create a May 2018 calendar.

My “29” has a dimple in it; I’ve written to see if I can secure a replacement.

I am

I am