Once the black dried on the C1A 4R4 envelopes, I added a red layer, with my name:

I love the “taking the smallest element and making it the biggest” aspect of this design: the postal code is often a throwaway item added (or not added) to a return address; this flips that, and makes it unavoidable.

My contacts within Canada Post suggest that if you mail a letter addressed simply to “Rukavina C1A 4R4” there’s a good chance it will get delivered; this puts that to the test, at least on the return side.

When I bought the Golding Jobber № 8 letterpress from Bill and Gertie Campbell, Bill generously spent a couple of hours with me showing me some of the trickier bits of using it.

One of the things he taught me is how to print envelopes. Because of the way they’re constructed, printing on envelopes often means printing on different thicknesses of paper at the same time. If you just print as you normally would, the impression will be uneven because the pressure will be uneven on different areas.

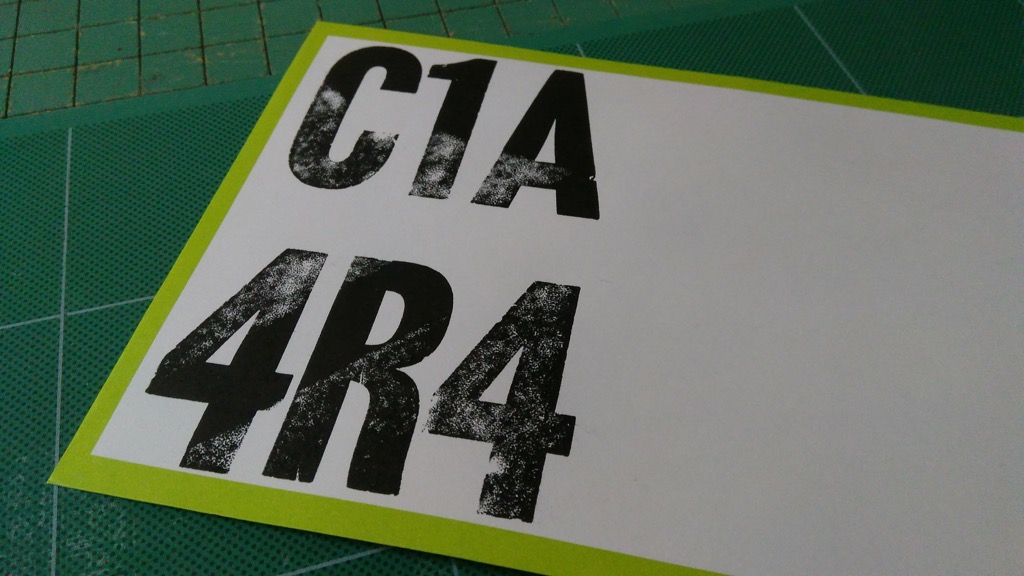

You can see the result in this first print of a C1A 4R4 envelope I printed today:

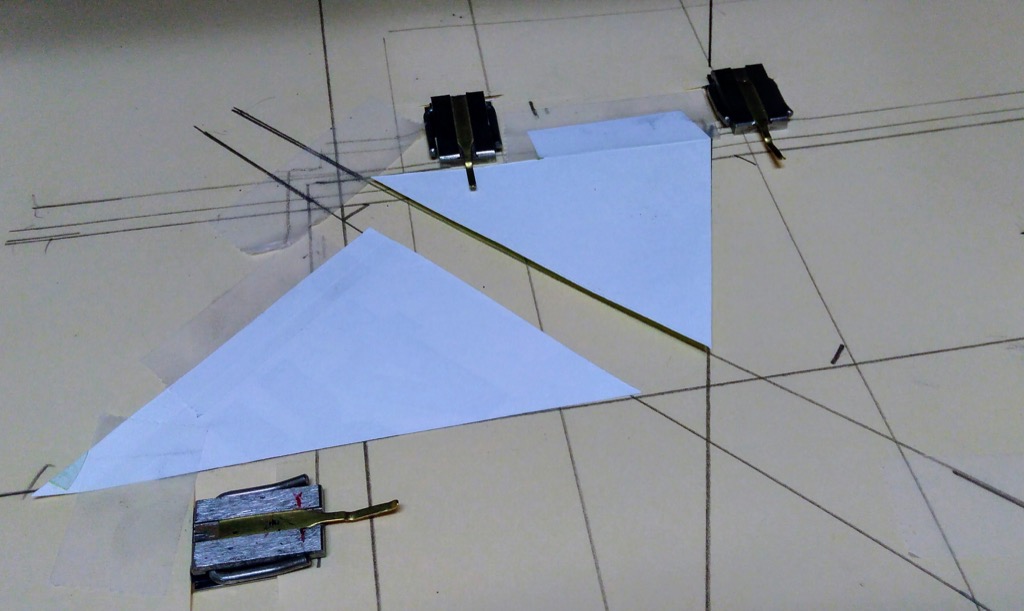

What Bill showed me is how to construct a sort of paper “shim” under the envelopes so that everything ends up being the same thickness when printing. To make the shim, I took the envelope I test-printed, and chopped it up with a knife, using the print as a template for the areas that needed buttressing. The result looked like this:

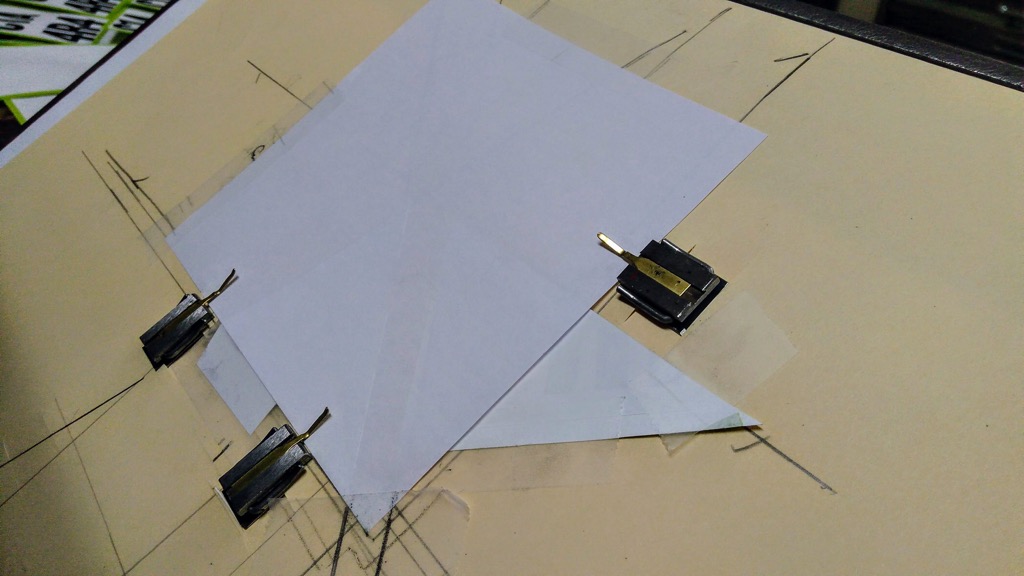

I covered the shim with a layer of paper to avoid it getting caught up in the envelopes while printing, ending up with this:

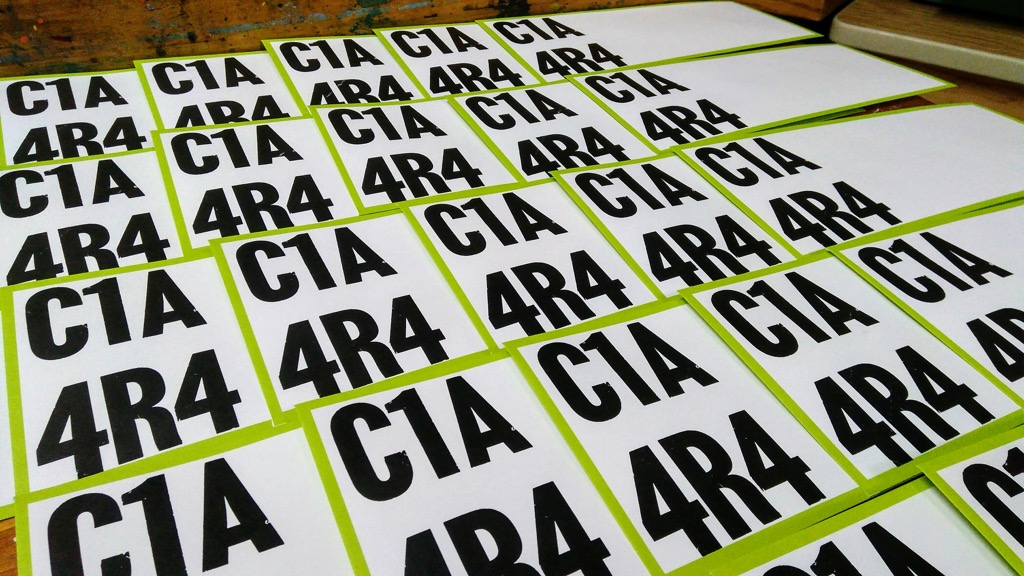

With the shim in place, the envelopes printed cleanly across the entire surface:

I’ve got one more run to take at these envelopes, printing a line, in red, between the C1A and the 4R4; I’ll do that once the black has dried.

With temperatures in the mid-teens and wearing Spring jackets and sneakers for our after-supper walk, it’s hard to believe that 3 years ago this week there was still a lot of snow and ice on the ground, the result of 2015’s endless winter.

Here’s 2015 in our backyard vs. tonight.

,

,

In an exchange that reflects blogging the way it’s supposed to happen, Ton left a comment about energy usage data in the Netherlands on my post about my postal code. And then, when I asked him a question about this, he responded with a detailed and very helpful blog post of his own.

One of the things he revealed there is that his house in the Netherlands consumes 3700 kWh per year of electricity.

Because we’ve been doing detailed logging of our own electricity consumption, this gives me an opportunity to compare.

Our Maritime Electric electricity meter read 1702925 on April 24, 2017 and reads 2246469 as of one minute ago, a difference of 543544, or 5435.44 kWh.

This means that we consume 1735 kWh–46% more–per year for our detached single family home of three than Ton’s detached single family home of three.

Our friends Bill and Michelle, who are also participating in my electricity and water monitoring project, and also have a detached single family home of three, started out at 3125321 and are now at 3615162, a difference of 489841, or 4898.41 kWh, which is about 10% less than us, and 32% higher than Ton.

I’d be interested in drilling down into the primary reasons why our electricity consumption is so much higher.

Over March Break in Halifax, Oliver and I stopped in to see our friend Nardag*, daughter of our old friends Bob and Yvonne. I’ve known Nardag all her life, and it still seems odd that she’s now a independent young woman. It was wonderful to see her.

While we were visiting, Nardag’s neighbour was over for a visit, as it was Friday, and Friday was the day set aside for smoothie bowl breakfasts (in this, she explained, she takes after her father, who is similarly regimented in his habits).

What is a smoothie bowl, you ask? I put this question to our hosts: “it’s a smoothie, but in a bowl,” they replied in unison, “with things sprinkled on top.”

They offered to whip up a couple of extra smoothie bowls for us, and we eagerly agreed. Shortly they were placed in front of us and an array of the “things” laid out surrounding. This array included everyday things like nuts and shredded coconut, along with various other mysterious powders, some of which we were warned were rather bracing to consume.

We opted for a safe sprinkle of known things, and enjoyed the experience immensely.

To the point where we have now introduced the radical smoothie bowl concept into our own breakfast routine.

I remain unclear as to whether Nardag and her neighbour invented the smoothie bowl—for all I know Californians have been consuming them for decades—but I’ve opted to believe so.

They’re simple to make: prepare a smoothie as you normally would, albeit perhaps a bit thicker. Pour it in a bowl. Sprinkle to taste with coconut, yak horn powder, etc. Enjoy.

* Nardag is not Nardag’s actual name. On the day she was born, Catherine got a call from her mother and misheard her name, which is actually Nadja, as Nardag. While this struck me as an odd name, her parents have a Bohemian bent, and so it was not outside the realm of possibility. As is my wont, I embraced the mistake entirely.

Oliver goes out to Crapaud every Sunday afternoon for 90 minutes with the brilliant art educator Jennifer Brown. Every week they tackle a new medium, or a new artist, or a new subject. Today it was making block prints of inuksuit.

For the longest time, if you wanted to resize a EBS volume (aka “your disk drive”) attached to an Amazon Web Services instance (aka “your server”), you had to go through a dance that involved shutting down the instance. This was relatively simple in spirit, but terrifying enough in practice that I procrastinated doing it as I watched the size of my primary volume on the server powering this blog gradually fill up.

Today I reached 100% and I had no choice: fortunately, things, it turns out, have become much easier. All I needed to do was resize the volume in the AWS console (select the volume, click Modify, change the size) and then extend the Linux filesystem to use the new capacity with:

sudo growpart /dev/xvda 1

sudo resize2fs /dev/xvda1

From start to finish it took about 2 minutes.

Now I’ve got gigabytes of free space to slowly fill up in the weeks and months to come, and the confidence that when I need to increase capacity again I won’t need to go into hiding to avoid it.

My postal code for the last 18 years has been C1A 4R4. As postal codes go, it’s a pretty good one: it has been easy to remember, and it looks sharp on an envelope.

It wasn’t until I went to mail something to a friend just up the street that I realized that there are other people with the same postal code, and I got curious as to how many of us there are.

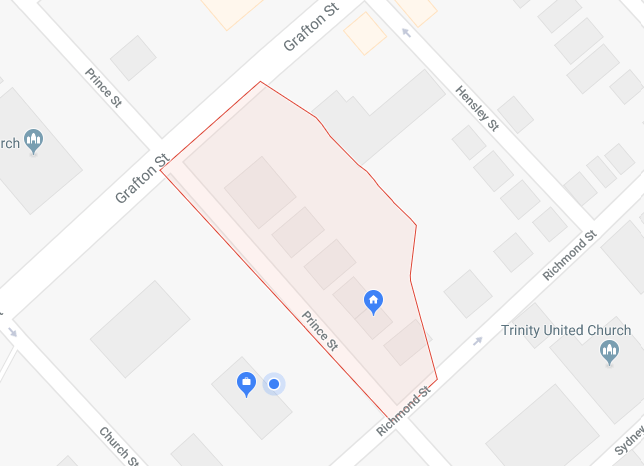

Google’s map of the postal code’s boundaries shows C1A 4R4 as including all the buildings on the east side of Prince Street from Richmond Street to Grafton Street:

Indeed, Canada Post’s reverse-postal-code-lookup tool shows 24 addresses fall under the postal code:

- 96 Prince Street, with 96-A and 96-B

- 98 Prince Street

- 100 Prince Street

- 104 Prince Street

- 106 Prince Street

- 108 Prince Street, with 108-1, 108-2, 108-3 and 108-4

- 114-1 Prince Street, with 114-2, 114-3, 114-4, and 114-5

- 120 Prince Street

- 124-1 Prince Street, with 124-2, 124-3, 124-4, 124-5, and 124-6

On a roughly-pasted-together composite of Google Street View images, these addresses look like this:

There are 6 buildings in all: 2 single-family homes (ours, at 100 Prince Street, is one of them), 2 multi-unit homes, and 2 multi-unit apartment buildings. Spread across these 6 buildings there are 19 distinct residential units and one office/retail space. A rough estimate, assuming an average of 2 people per unit, then, would see about 40 people sharing the postal code.

The walk from 96 Prince Street to 124 Prince Street is about 79 metres; Google says the distance can be walked, cycled or driven in about a minute.

Often, when I’m in a hurry, I’ll often write my return address as “Rukavina / C1A 4R4,” reasoning that our letter carriers are experienced enough to sort things out if the letter ever needs to be returned.

I’ve become fascinated recently with very-small-scale geographies, inspired, in part, by Flaneur magazine, which focuses on one street per issue: perhaps the best thing to do when everyone else is trying to communicate with everyone, everywhere, is to reach the people in my postal code?

I am

I am