Bunty Albert died two days ago.

I knew Bunty only at the very end of her life: our shared interest in fountain pens brought us both to “Pen Night” at The Bookmark.

At the January meeting, just three weeks ago, Bunty showed us a vintage fountain pen that had been owned by her mother; it was a lovely pen, and Bunty spoke of it with a kind of workaday reverence.

Reading Bunty’s obituary today, I realize that I knew only a thin slice of the engaged person she was; that she opted to brave a cold winter night to sit around a table to talk about fountain pens, though, speaks to someone determined to live life to the fullest.

“See you next time,” I said to Bunty as she took early leave from the meeting.

I won’t, alas. But her spirit will remain there when we gather again this Sunday.

Oliver released his 2019 Oscar nominations today, with his own categories, like “Best Special-Needs Awareness” and “Best Historic Movies.” He’s been working hard on this all week, a good use of his downtime from Wednesday’s wisdom teeth removal.

One day in the late 1980s I got an urgent telephone call from my friend Simon: municipal and school board election nominations were closing that afternoon, and if I ran down to Peterborough City Hall to turn in a nomination there was a good chance I could get acclaimed.

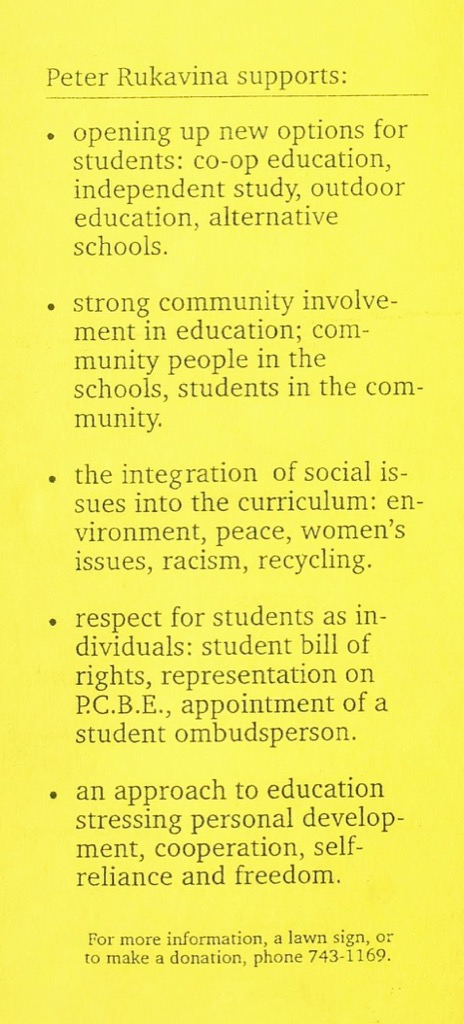

As I was fresh off 13 years in public school, and had recently dropped out of university, I had a lot of ideas about school and education, and the chance to offer my recently-gained experiences to school board governance seemed like a good idea, so I took Simon up on his suggestion.

As it happened, there must have been many other such calls made that afternoon, as by the time nominations closed I was one of 13 candidates for 8 positions and was thus faced with the prospect of actually running an election campaign, something I had not anticipated.

I would like to be able to say that I jumped in with both feet, but I did not.

I didn’t jump in with no feet, mind you. But I realized I had no taste for door-to-door campaigning after I’d knocked on less than a dozen doors. I did, however, participate in a televised debate, I had election signs printed (by the talented Grant Fines), and I did develop a platform of sorts, preserved for history on this flyer that I recently found in a portfolio I thought long-lost:

Re-reading that platform now I’m struck with how little my ideas have evolved over the last 30 years: I might not phrase my platform the same way today, but the bedrock upon which it was based is still, mostly, the bedrock of my education thinking today. I’m pretty sure that the platform would appeal to Oliver too.

In the end I flubbed the campaign: I was awkward and dumbstruck during the debate, too shy to effectively campaign, and I ended up 13th of 13 when the ballots were counted. I don’t begrudge the experience, however, as it gave me a small window into electoral politics that has served me well when I see others putting themselves forward.

During my year at Trent University I made the acquaintance of a fellow student, David Kennedy, impressive for his intellect, his creativity, and his well-resourced shoulder bag.

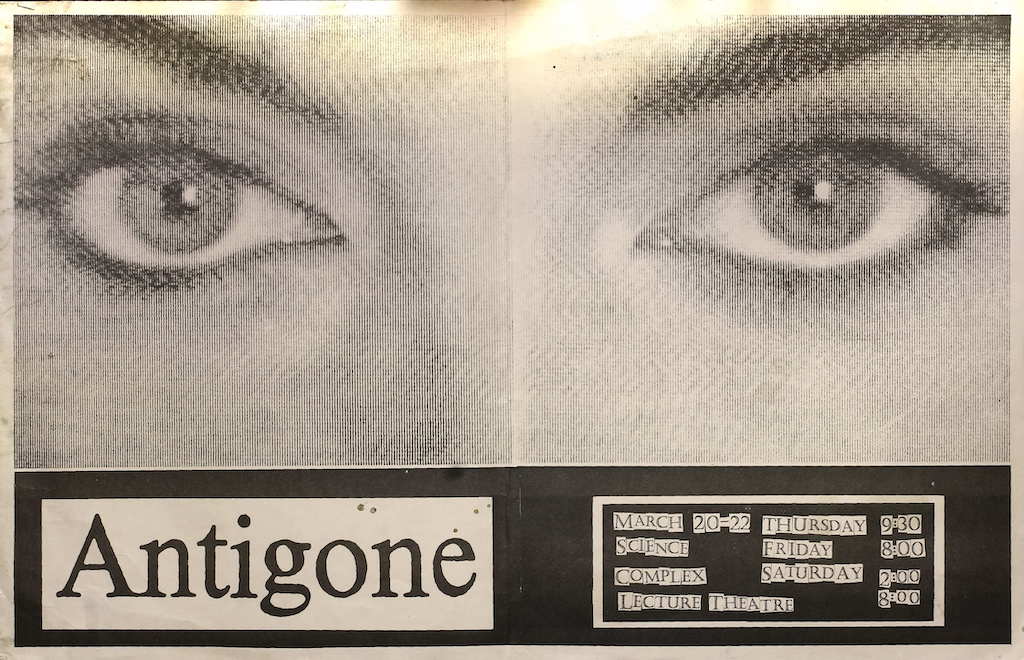

David set out to direct a production of Antigone in the spring of 1986, and I offered to make this poster, using a concept he came up with. This is what resulted, the first piece of real design work I ever did:

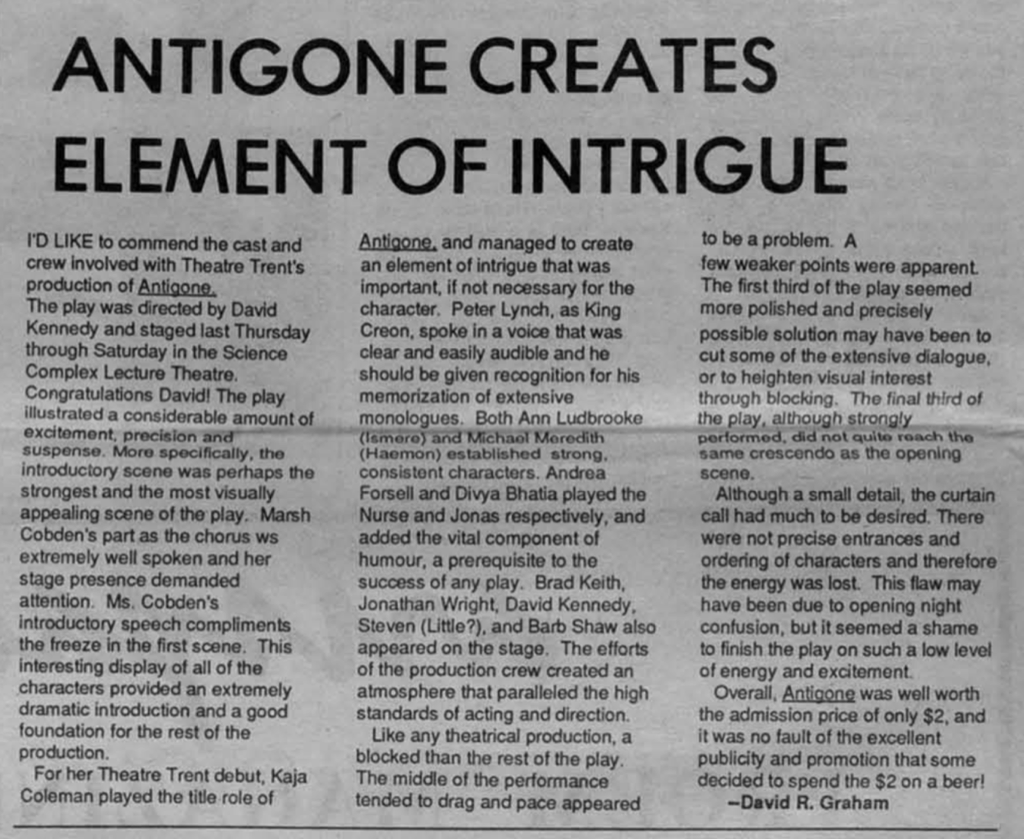

It was an arresting production, if memory serves, and the first piece of theatre I’d ever voluntarily attended. It was reviewed in Arthur (the Trent student newspaper) the following week, something I was able to find thanks to the diligent work of archivists at Trent:

There are many names in that review that I recall; Marsh Cobden, for example, went on to own 425 Stewart Street in the years after it was occupied by a rabbit’s nest of friends of my acquaintance. I lost track of David Kennedy over the years; I wonder what became of him.

I loved making that poster; it’s not an exaggeration to say that inspiration I got from crafting it led me to cultivate an interest in the graphic arts, which led me to work in newspapers and, ultimately, on the web.

Joe Schlesinger on life as a patient:

But I refuse to let all that affect my taste for life: I still have so much to engross the heart and engage the brain.

Schlesinger died today; he may have been Canada’s most thoughtful journalist.

Oliver is forever misplacing his headphones. Generally they end up under the sofa, or inside the sofa, or on the side table, or under a pile of books. Sometimes space aliens take them for awhile. Headphones locating has been a substantial source of stress in our daily life.

So we installed a headphones hook.

Problem solved.

It’s been 20 years now since Island Tel began its brand transition to Aliant, and 16 years since Aliant completely retired the brand names of its merged component regional telcos, yet vestiges of the old name remain.

Like this telephone booth in the Atlantic Superstore in Charlottetown (located, ironically, just a few hundred metres from Island Tel’s former headquarters). The logo is one that existed during the transition between Island Tel and full-on Aliant, designed in that regrettable era of globes and a swoops.

I was reading The New Yorker profile of Glenn Greenwald this morning, and read, just before I put it down to go across the street to the office, this characterization of the relationship between Greenwald and Edward Snowden:

On Instagram, Greenwald posted a photograph of Snowden eating an ice-cream cone. Snowden had told me, “We’re not like buddy-buddy. There’s a distance. We don’t talk about our personal lives. We don’t call every Wednesday and say, ‘Hey, you want to play bingo online?’ ”

Five minutes later I walked outside and, frozen in the ice between the sidewalk and the road, I spotted this cast-off bingo card (not a winner):

I have not said the word “bingo,” nor thought of bingo, in a long time; now it’s everywhere.

Also, how would you play bingo online with someone?

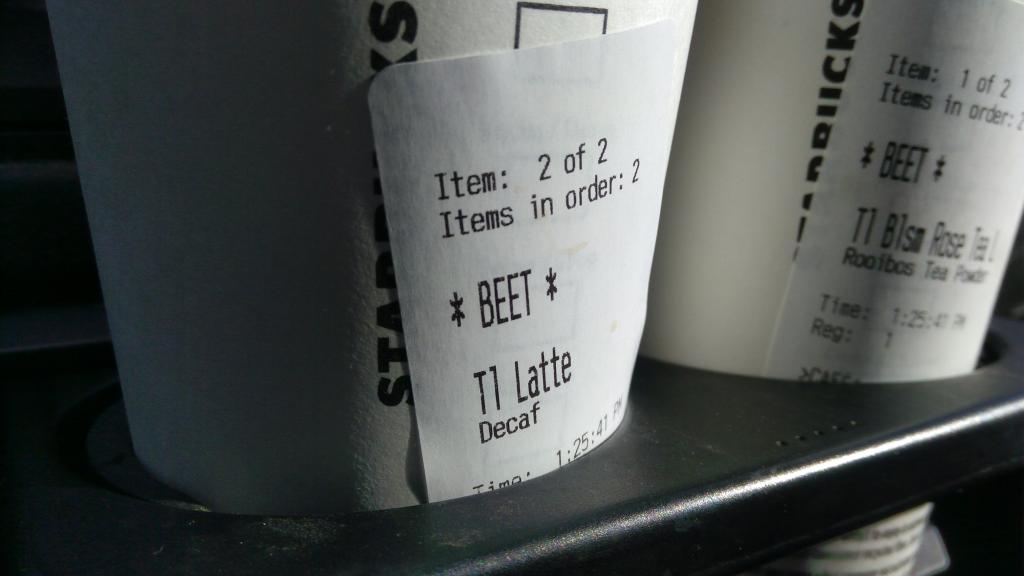

Every Saturday afternoon, en route to Crapaud, Oliver and I have lunch at A&W followed by a drink at Starbucks.

The drive-thru line at Starbucks today was really long, so we opted to go inside to order, and I was asked for my name by the order-taker.

“Pete,” I told her, using the pseudonym I fall back on for such purposes.

Seeing through my charade—he’s obviously not a Pete, she realized—my cup was labeled BEET.

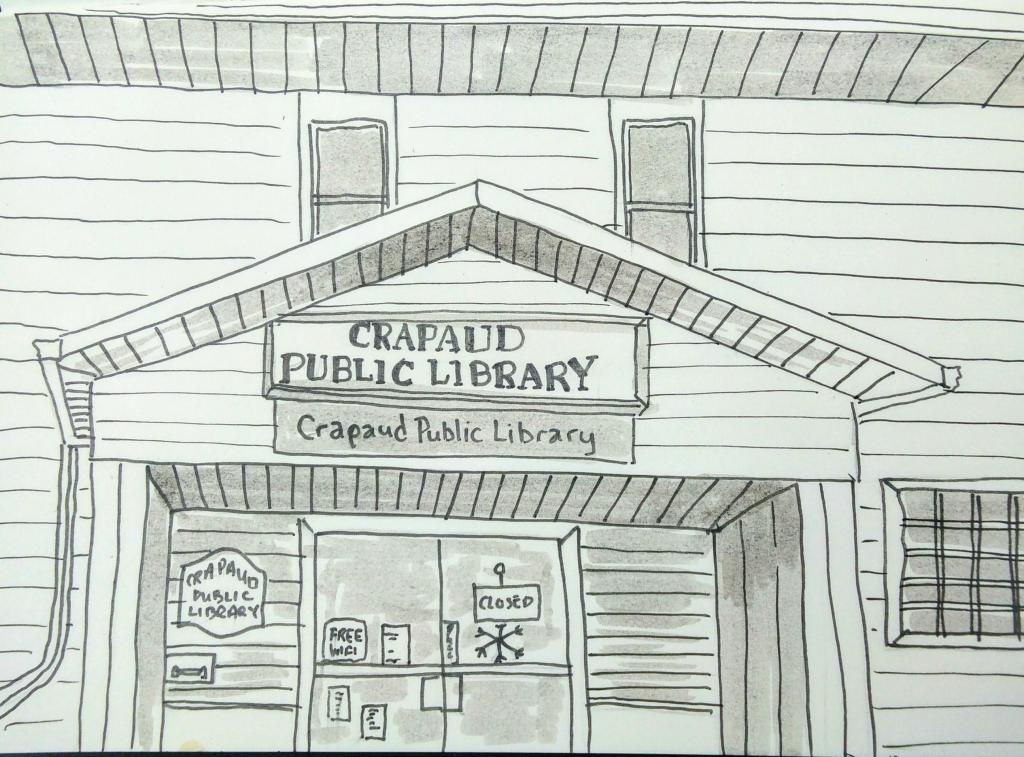

I was hopeful that I would be able to tap into the free wifi at the Crapaud Public Library this afternoon to watch the speeches at the PC leadership convention.

But the library was closed, the wifi locked down, and I was out of luck (why all Islanders don’t simply have automatic wifi access at all Island libraries, without bureaucratic rigmarole, I do not understand).

My consolation prize was the opportunity to sketch the library entrance from my position in the driver’s seat of my (increasingly freezing cold) Jetta.

I am

I am