Buried at the bottom of a cupboard in our library, I found the stained glass fish that used to grace our piano window. I restored it to its former home.

As the rest of our world unravels, here on the Island a seal gets a ride in the back of a police cruiser.

Every reporter deserves the occasional exploding bus-fire eater-magic cat story: today was Shane Ross’ turn.

A view from the back hallway window at 100 Prince Street. The tracks on the right are human tracks, mine, made during my regular trudge back far enough to get a good look at the snow and ice on the back roof. The tracks on the left are from animal unknown, and I just love them.

I ran into my friend Suzanne this week in the Sobeys checkout line. I hadn’t seen her in a long time, since the before before the before. The effect was not unlike what I expect opening the door of the fallout shelter to emerge into the nuclear winter would be like: we compared notes, as one might, on how sheltered life was going, and drew a little strength from knowing we’d shared something of the same experience.

Megan Hallinan wrote in November about a bar in Rome that forbid COVID talk:

There’s a bar in Rome (bar in the Italian sense meaning that it primarily serves coffee) where they have taken the revolutionary step of forbidding talk about COVID by anyone who steps foot inside. It’s a refreshing idea, and at this stage in the pandemic calendar one that I don’t think many people will complain about.

On reflection, I realized that most of my conversations, for as long as I can remember, have been COVIDy: Where’d you get that mask? Are you still in Code Magenta? You went to see live theatre?! How you holdin’ up? What’s the deal with celery? (COVID talk apparently involves a lot of folksy contractions).

Between COVID talk and grief talk (and, for a while there, insurrection talk) there’s not a lot of room left over for loftier ruminations. I could use some lofty ruminating.

Years ago my neighbour (and Catherine’s roommate) Mike Johnston pitched a talk show set on a bus, and snagged Margaret Atwood as a guest for the pilot:

Even more impressive, Johnston finagles the participation of Ms. Atwood. Drawing on his friendship with the late Canadian poet Al Purdy, whom he used to book for poetry readings at Peterborough’s Red Dog Tavern, Johnston coerced the author to film an interview for the pilot; Atwood appears gracious and bemused in the segment, and she even signs the roof of the bus in a good-luck gesture. “She was awesome,” he says. “And she had really great skin, too.”

I was thinking about Mike and Atwood this morning because my social worker told me that I could be intimidating, which I found surprising, as I have never thought of myself that way. Atwood, surely, is the most intimidating living Canadian, and I wonder whether she feels that. Or, like me, considers herself a lucky idiot. What kind of friends do you end up with if you’re intimidating?

As if by magic, midway through writing this, my friend Martin phoned and offered to deliver Vietnamese sandwiches for lunch. He arrived 45 minutes later, and we spent the next 2 hours (mostly) not talking about COVID (or insurrection). We did, however, talk about grief for a bit.

Earlier in the week Martin pointed me to a post by his friend Ivan about grief. He mentions the Widow We Do Now? podcast, which I indirectly led him toward, a very helpfully irreverent podcast for people with dead husbands (and wives) that, like Ivan, I’ve been binge-listening.

I wrote to Ivan after reading his post, in part:

I don’t know why hearing tales of those on a similar journey is comforting, but it is.

I’ve found the same thing to be true of the monthly grief support group: who would think that a Zoom populated exclusively by the grieving could be anything other than a catalyst for embarrassed silence. But, no, it turns out there’s a magic to it, and that talking and listening to others who, no matter who and when and how, are grieving is helpful. In a way, what we talk about is irrelevant: just showing up to bear witness to each other is the key.

The estimable Rose Cousins released a lovely cover of Whitney Houston’s I Wanna Dance With Somebody this week (Rose Cousins’ middle name is Millicent, by the way; that endears me to her even more).

The night before Oliver was born we watched Message in a Bottle, starring Whitney Houston’s friend (and former costar) Kevin Costner. I’d forgotten until just now that the plot concerns love letters written by Costner’s character Garrett to his dead wife Catherine, with the dramatic tension being “Garrett cannot quite forgive Catherine for dying and leaving him.” I’ve been there. The tension resolved only when, in a sense, Garrett emerges from his fallout shelter.

Megan Hallinan’s post continues:

Much like politics, we’re all tired of talking about COVID: what it means and how it influences every single decision we make. And when we are not talking about it, we’re all still thinking about it. My internal chyron has had these same two topics looping around for the entire year and good God I am worn out.

As much as I’ve found talking about grief to be powerful and important and, in the end, necessary, I feel worn out in the same way: being defined by, and defining myself by, absence. It can be exhausting.

I’ve been reading John Kim’s book Single On Purpose, and this paragraph hit me over the head:

I’ll tell you why you feel lonely. Because what you get from an intimate partner is something you can’t get from anyone else. Because those conversations after work and those waffles on Saturday morning help the world make sense. Because spooning puts you to sleep like a little baby. Because tongues feel fucking good. Because looking into someone’s eyes for longer than three seconds reminds you that we’re not meant to do life alone. Because being emotionally naked makes you feel alive. Because you can’t really tell your friends how your day went every single day or you won’t have any friends. Because we’re meant to give and share, lose ourselves and find ourselves through others, and love, hard. Because ordering in is so much better when you have someone.

If I’d read that a year ago it would have plummeted me into a cascade of tears as I lay, paralyzed, on the cold metal cot in the back corner of the fallout shelter. Reading it today doesn’t do that, because, hell yes, I’ve been there, I know that, and wasn’t that a blessing. But also because I know that, even after the nuclear winter, nature finds a way, and it reminds me of life’s possibilities.

One of the things we return to frequently in discussions among the grieving is whether grief with a side of COVID has made the process easier or harder. Opinions vary: one person’s loneliness is another person’s time for quiet reflection; some take solace that the world is, in a sense, also grieving. That’s something that’s always hit home with me, and I now again find my own situation mirrors that of the world around: with the back of the COVID curve seemingly broken again, and the pace of vaccination picking up, the fallout shelter doors, if not enthusiastically thrown open, are at least no longer welded shut.

To the point where, when I write “Who knows what might happen next?”, it can be a statement of possibility and hope, not of despair.

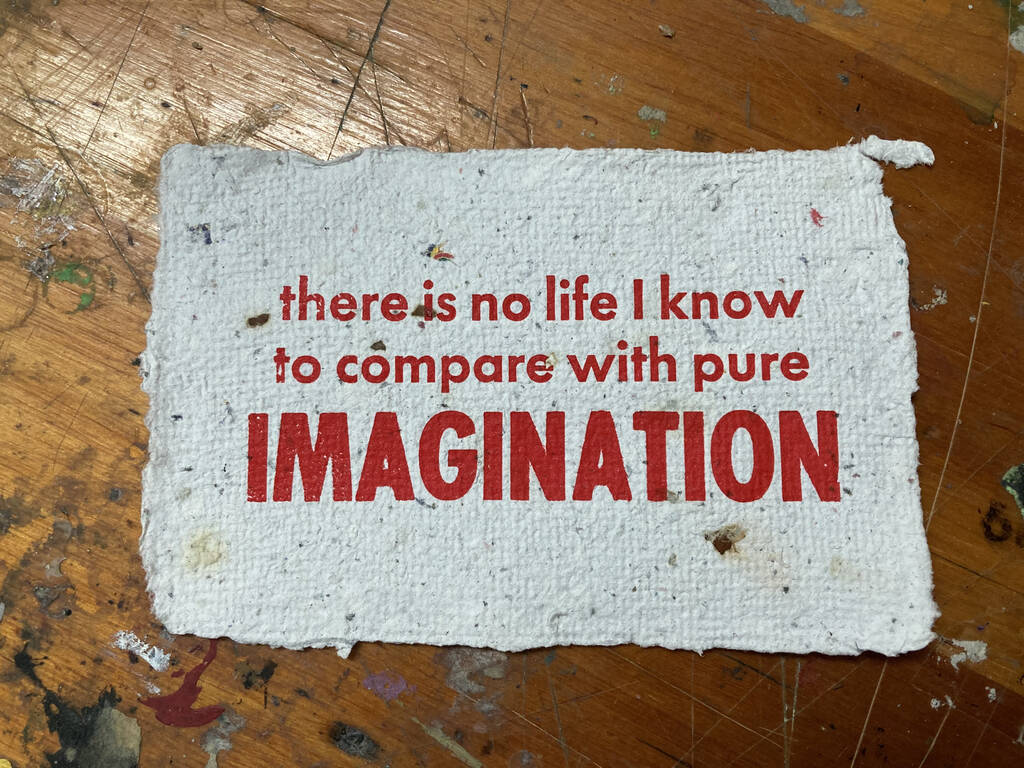

A year ago, in the midst of Grief 1.0, I experimented with turning the cards and flowers we received when Catherine died into handmade paper. It took a lot of experimenting, as it was both my first try at paper making and I only had the barest minimum of scrounged equipment, but two weeks later I ended up with 50 index-card-sized pieces of satisfying flower-infused paper.

My plan at the time was to use the paper to create a touchstone in Catherine’s memory that I could, with pleasing circularity, send back to those who’d sent the cards from which the paper was made.

Life, COVID, and a sense that I wasn’t quite ready to finish this project intervened and a year passed. This morning, though, I woke up resolving that today was the day.

I printed a line from the lyrics of Pure Imagination, sung by Gene Wilder in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and composed for the film by Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley. The film was one of Catherine’s favourites, and the sentiment of this line gets to the heart of her ethos. The craggy imperfections of the paper and the crisp ruddiness of the type also happen to be a good avatar for where my artistic sensibilities met Catherine’s: in general, I would avoid the roughness and she would avoid the type.

An impressive packaging refresh from The Handpie Company. We’re having both before and after for supper tonight. (Good to see that Pie Man is still part of the branding; I love Pie Man).

Pro-tip: if you brush your handpies with milk or egg before you put them in the oven, the difference in the outcome is palpable: you get flaky, moist goodness rather than rock-hardness.

Say what you will about Christianity, it’s got some solid rituals, and the Shrovetide, Lent, Easter trilogy is the most epic.

Today, Shrove Tuesday, is an important inflection point in the epic, a day of consideration and absolution, girding the loins for the 40 Lenten days until Easter.

As happens every once in a while, my birthday falls on Easter Monday this year, meaning I’ve 40 days left until I cross over in the grand select list from “45-54” to “55-64,” and so this Lenten season presents me with a handy opportunity for personal reflection, alongside my Christian neighbours. Oliver asked the family mailing list what we’re giving up this year; I said “confusion,” in jest, but, on reflection, perhaps not such a bad choice.

Tomorrow is Ash Wednesday, and, like all else, COVID requires adaptation; at St. Paul’s they’re giving out “bubble ashes”:

The Ash Wednesday service will not include the individual imposition of ashes. Instead, we will impost the ashes on a symbol of the community and have individual cups of ashes available for group bubbles. These bubble ashes can be used in a variety of ways: they may be imposed on the foreheads of members of your bubble; they can be sprinkles in a garden or on a house plant; or, well, we don’t know, please let us know if you’ve thought of a creative way of using the ashes.

That’s delightful, and a demonstration that rituals need not be rigid in their interpretation as long as the spirit is hewed to.

According to The Shetland Dictionary, a noost is:

the place, usually a hollow at the edge of a beach, where a boat is drawn up.

Watch the Good Shepherd IV enter the water from its noost; it is an impressive noost indeed. The ferry serves the Scottish island Fair Isle, the remotest inhabited island in the UK.

I am

I am