For reasons only related to his mentioning of battery levels and automation in his 2021 Week Eight update, I was prompted by Paul Capewell to see if there was a way to send the current battery level of my iPhone to a URL where I could archive it.

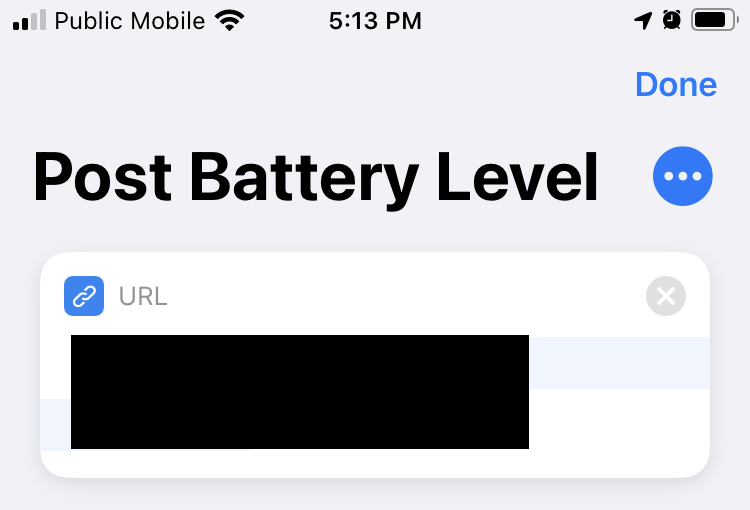

This turned out to be pretty easy; because there’s no simple way to share Shortcuts, here are some screen shots. I created a new Shortcut called Post Battery Level and added the URL where I wanted to send the value (I’ve redacted that URL in the screen shot):

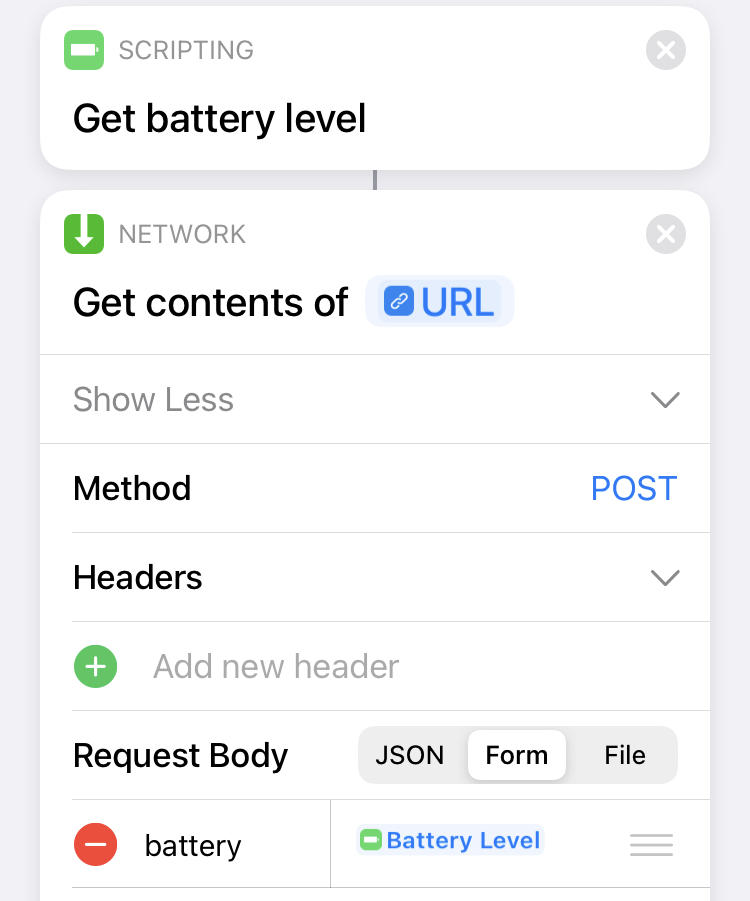

Next I get the battery level (there’s a built-in scripting component for this — search for ”Get battery”), and use the “Get contents of URL” component to HTTP POST the value as a form, with the battery level sent as the “battery” field:

On the server side, the simplified version of what I do is this, a short PHP script to grab the value and stick it in a MySQL table with a timestamp:

<?php

if ($_POST) {

$db = new mysqli("localhost", "REDACTED", "REDACTED", "REDACTED");

$query = sprintf("INSERT into battery (battery_date, battery_level) values ('%s', '%s')",

strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S"),

mysqli_real_escape_string($db, $_POST['battery']));

if (mysqli_query($db, $query) === TRUE) {

header("HTTP/1.1 201 OK");

}

}

When I run the Shortcut, a new battery level row gets added to the table:

2021-03-01 17:09:14 82

2021-03-01 17:10:20 82

2021-03-01 17:13:28 82

2021-03-01 17:21:28 82

There’s one stumbling block if I want to run this, say, every 15 minutes: to do that requires either using the Automations tab in Shortcuts to create a new schedule for each time I want the Shortcut to run — 00:00, 00:15, 00:30, etc., 96 in all — or to set up a “repeat” loop in the Shortcut itself, with a 15 minute pause inside the loop, which works, but then renders the Shortcuts app unusable otherwise.

Perhaps in a future version of the Automations setup there were be the “run every X minutes” option that I wished there would be.

In any case, thank you to Paul for the diversion.

On exigent COVID days, our Premier has taken to appearing for a few minutes of scene-setting cum pep talk before Dr. Heather Morrison. When what we really want to know is whether school is cancelled, we may have ordered pizza from a COVIDy place, or what the case count is.

Few would dispute that the Premier has kept a cool head throughout the past year; there’s a time to lead, though, and a time to get out of the way.

As a result of the Modified Code Red here (I still have no idea what the “Modified” means), the dental appointments that Oliver and I had scheduled for tomorrow morning were cancelled. The next available appointments were September 13. Which gives you some idea of the spill-on effect of taking three days out of a dental office already running at reduced capacity.

Fortunately we’re in good dental health, having been to the dentist last fall; the nice thing about being on an every-6-months cleaning schedule is that a delay like this just temporarily kicks us back to a more typical once-a-year. Add that to our upgrade of home toothbrushing infrastructure and I think we’ll be okay.

Let’s all raise a glass to the medical and dental secretaries of the Island who will be spending today building new jigsaw puzzles.

In A Journal of the Plague Week 50, Jessica Spengler writes, in part:

But we’re not out of the woods yet, and “end of lockdown” does not mean “end of pandemic”. There seems to have been a lot of confusion about that over the past year, with too many people equating what they’re allowed to do with what it’s actually safe to do. Bars and restaurants didn’t open last summer because it was safe, they opened because an economic decision was made at the expense of a public health decision (and the subsequent rise in infections—especially following the “Eat Out to Help Out” scheme—which ultimately led to our second lockdown bears that out).

While I think there’s a general awareness that anything short of “everyone stay in your home and eat the dregs of your pantry for two weeks” is a compromise, I think many fall into the “if it’s allowed, then it must be safe” trap. I certainly have, by times.

Things have taken a turn for the anxious here on Prince Edward Island this week COVID-wise, with an uncommon number of new cases, cases not tied to travel outside the province. Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Heather Morrison has held three briefings in the last 24 hours, the latest of which just ended.

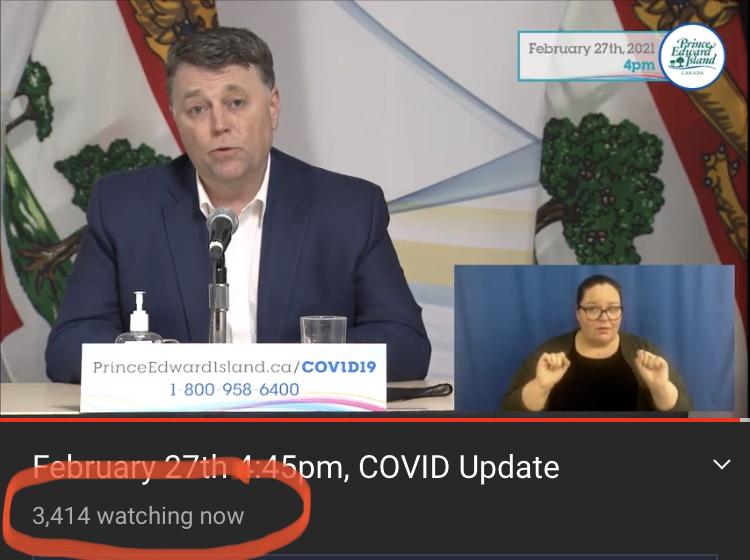

I noticed that as the briefing was finishing up there were 3,414 viewers in the YouTube stream, and that’s only one of the places it was available. There are about 103,000 adults on the Island, so that means at least 3% of us were watching, likely many more.

We went for a walk at Fullerton’s Creek Conservation Park in Stratford this afternoon. If not for Oliver visiting a few times last year without me, I never would have known it existed.

The sun was shining and the trail had been packed by those who walked out earlier; it was a very pleasant walk to the overlook that affords a view of Fullerton’s Marsh.

Although the park is clearly signed prohibiting snowmobiles, snowmobiles clearly cut through regularly, so I’d avoid the area around dusk or when visibility is poor.

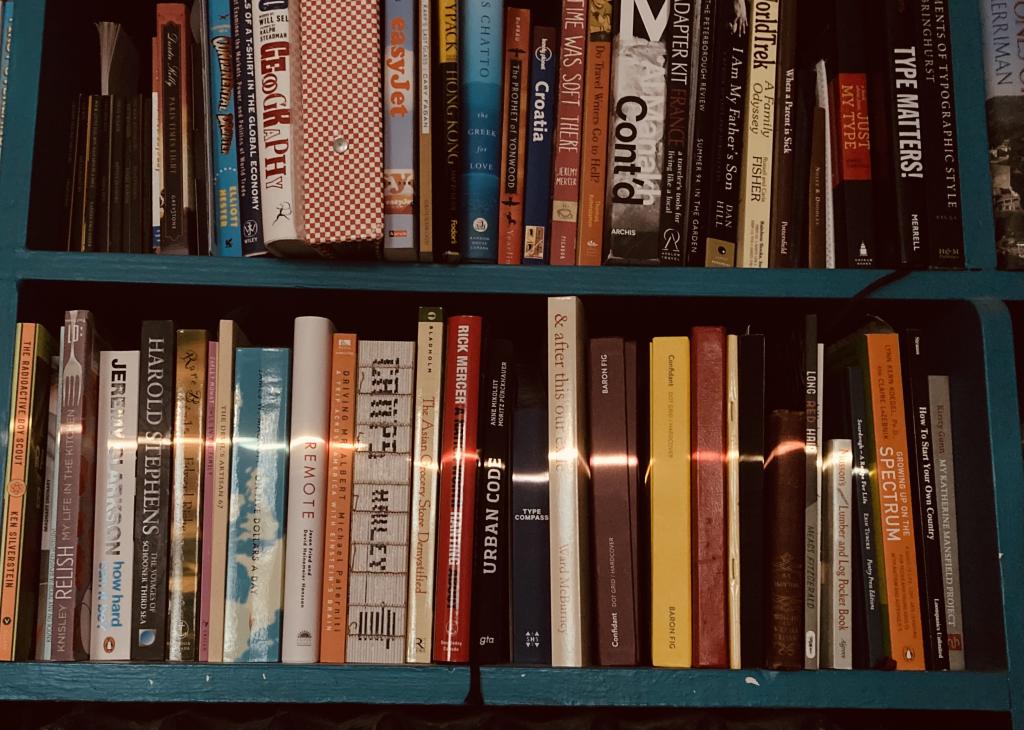

I walked into my bedroom late this afternoon to find the sun shining through the blinds, for a fleeting moment, so as to cast a single perfect sunbeam on my bookshelf.

I walked into the kitchen tonight to put the dishes in the dishwasher and found a mouse standing on the stove looking up at me. It was a cute mouse, as mice go, but still.

For the longest time it was Catherine who was our liaison to the mouse kingdom: she grew up on a farm, and was well familiar with their ways.

A few years ago, as moving around became more difficult for her, and as I started to be last one to bed and first one up in the morning, I had no choice but to take over the diplomacy. I did not come by it honestly, and I still don’t. But I’ve figured it out.

It’s unusual to see a mouse around this time of year: their interest in our kitchen is generally restricted to a few weeks in spring and a few weeks in fall. But here was a mouse—a cute mouse, but still—in the middle of the winter. So I set the traps, with a barely-there amount of peanut butter, as instructed by my physicist friend, and in the morning, if things go according to plan, it will fall to me—who else is there—to empty them.

You may be asking “how can he go to sleep at night knowing that mice will probably be setting up camp in his bedcovers while he sleeps?” That is a good question.

The answer lies in the nature of my bedroom door, which, fortunately, is magic.

My bedroom door, like most of the doors in this 194 year old house, doesn’t close smoothly. But it does close, if given a little shove, and that is the source of its magic.

When Catherine’s illness got to the point where she needed a bed of her own, and moved across the hall, for the first time in many years I was sleeping by myself every night. It was cold and lonely, yes, but in a way also a sanctuary: a place all my own. The shove and gentle thud when I closed the door at the end of every day at bedtime, long after Catherine and Oliver were fast sleep, became a kind of airlock for for me, an avatar for keeping whatever exigencies might have filled yesterday, and might again fill tomorrow, at bay.

During the years Catherine was sick, that door allowed me some small measure of personal geography; I credit it, and its thud, for helping me keep my head above water.

It also proves useful in any number of other ways: it’s very helpful for meditation, for example, to have the rest of the world not exist for a time. And it keeps the mice, and, indeed worry about the mice, on the other side.

Good night.

I love William Denton’s imagination:

In this STAPLR composition, one one-minute iteration of Vexations is played for each minute of help given at any desk at York University Libraries that day. It keeps a running counter of how many more minutes it should play. Let’s say that at 0900 someone checks their email and answers a quick research question that takes them five minutes. They enter that into our reference statistics system, where STAPLR sees it and counts 5. It starts to play five iterations. One minute later, the counter is at 4. One minute later, the counter goes down to 3, but there’s another question in the system, this time a virtual chat that took 10 minutes to answer, so the counter goes up to 13. After one iteration it goes down to 12, then 11, then up again if there’s another question. If the counter reaches 0 it will wait and start back up when there’s another question answered.

STAPLR is Sounds in Time Actively Performing Library Reference.

See also CBC Spark Interview: SoundCloud + Pachube + Energy from 2011.

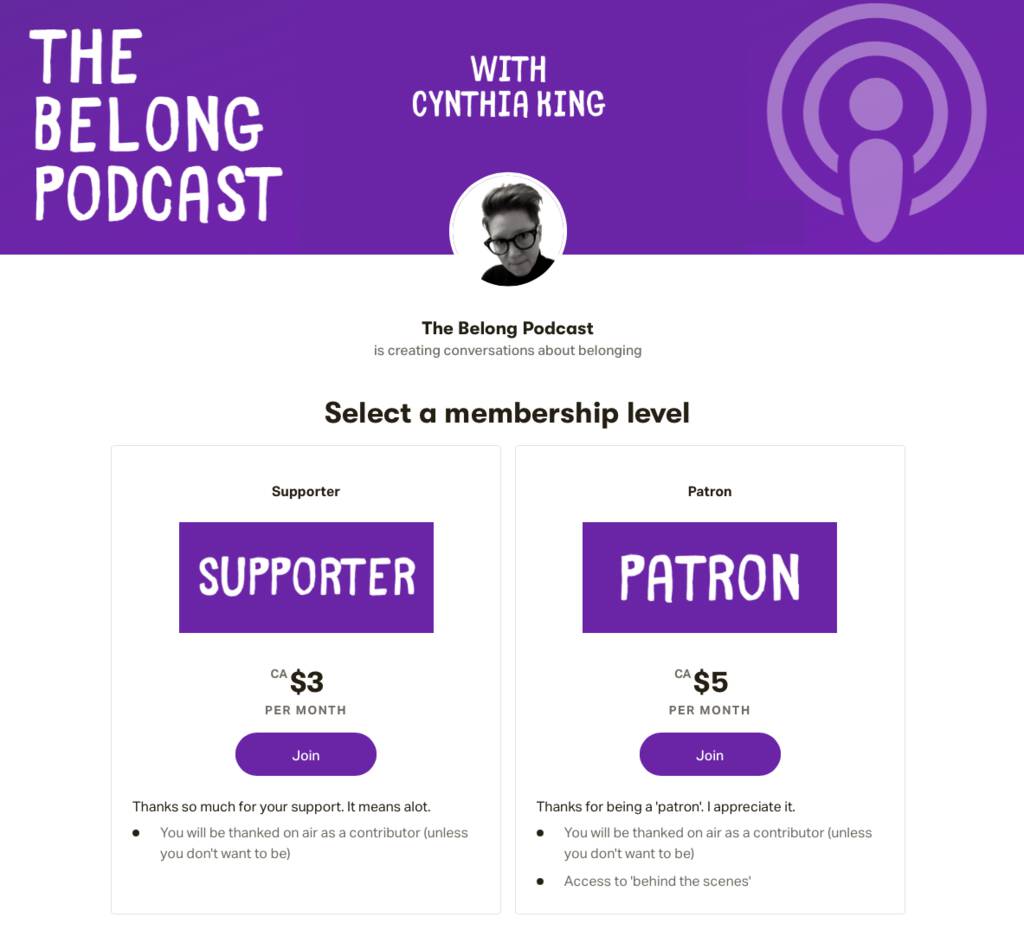

My friend Cynthia is producing The Belong Podcast. Among other things, it’s Canada’s preeminent source of interviews with people named Peter (Rukavina, Bevan-Baker, Mansbridge). But, more importantly and more interestingly, it’s a podcast where people, often people who’ve experienced not belonging, can discuss their lives.

When we talk about the new opportunities the digital realm offers for new people to make new things, Cynthia’s effort is what we’re talking about.

And now she has a Patreon, where you can support her in her efforts.

At this hour, I am her only patron, meaning that when she released an video update yesterday, BTS Video about barking dog, I was the audience. If that’s not worth $5/month, I don’t know what is.

Will you consider joining me in patronage, for $3 or $5 a month?

I am

I am