I took in a Karine Polwart concert via Zoom on Saturday afternoon, part of the Live To Your Living Room series. I have become an unrepentant fan of hers over the last year: Ophelia was my gateway in the spring, and I’ve made my way through her canon in the months since, so this rare-mid-pandemic opportunity to see her perform live was something I jumped on.

Along with, as it turned out, 999 others from around the world (I redacted names, as one generally would’t expect their name to be broadcast by way of attending a concert):

Other than Theatre Horizon Art Houses, this was the first live culture I’ve joined through my screen during COVID times. It was weird: not really like live music in the “crowded around a table near the stage at the old Trailside after having enjoyed the fish cakes and some huckleberry pie,” but also not really like watching a concert film. That there were others joining, even if I could sense them only when their microphones were brought up to applaud, did add to the experience a little, but in an aspartamey way: the acrid back-notes of the digital left me feeling unsettled and decidedly not immersed in the flow.

I think there are experiences to experiment with in the digital realm during these locked-down times – the aforementioned Art Houses are interesting in part because they don’t try to be “regular theatre,” and, instead, mine the opportunities of limitation – but my Saturday experience suggests trying to create a simulacrum of the traditional gig, via the Brady Bunch of Zoom, is not one of them.

Some years ago Catherine undertook a wholesale renovation of the room we variously refer to as “the office” and “the library.” I think she needed a plausible excuse to build a custom liquor cabinet, and things ballooned from there.

Below the bookshelves (and the liquor) are cupboards and drawers that I’ve seldom, if ever, looked inside. Today I decided to tackle them, thus encountering what amounts to the last significant cache of Catherinilia in the house.

I was only able to handle one cupboard, not because it was emotionally overwhelming, but because, well, what does one do with these things?

A WKRP in Cincinnati VHS box set. A brass candle stick. A half bottle of dry sherry. A 2007 calendar. Three ping pong rackets. A vase. A wooden truncheon. Several picture frames. A set of Victorian stereoscopic photos with viewer. A bag of paper coin rollers.

None debilitatingly cumbersome on its own, but together presenting an overwhelming “what the heck do I do with this?!” challenge.

The poem Want by Joan Larkin begins:

She wants a house full of cups and the ghosts of last century’s lesbians; I want a spotless apartment, a fast computer. She wants a woodstove, three cords of ash, an axe; I want a clean gas flame. She wants a row of jars: oats, coriander, thick green oil; I want nothing to store. She wants pomanders, linens, baby quilts, scrapbooks. She wants Wellesley reunions. I want gleaming floorboards, the river’s reflection.

As a friend has pointed out in reaction to my earlier ruminations about The Mountain of Things, Catherine and I could each play either role in that poetic drama: for every bottle of Dewar’s tucked away in a library cupboard, there was, at least at one point, a suitcase full of old telephones and computer manuals from 1988 in the attic.

Now that I’m the one left standing, though, the bottles of oats and coriander and thick green oil are equal parts reminders of my fallibility and hers, and digging through them by myself is sad and freeing and frustrating and emancipating all at once.

Maybe it was too emotionally overwhelming to open more than one cupboard.

,

,

From the description of the Croatian Long Distance Trail, words that could equally as well apply to life in general:

There are often villages and towns between the cities and settlements, which sometimes have shops that will come in handy for refreshments like cold juice, beer, ice cream or a sandwich. Let these shops be surprises, it is not good to know every detail of the trip.

I’ve been working with a social worker for the past six weeks on a kind of macroeconomic dig into my life, and where I take things from here. It’s been helpful in the same way that working with a psychologist was last year, but further up the stack, so to speak.

One of the things she mentioned at our appointment this week, more of a casual aside than a suggested plan of action, was, to paraphrase, that personal growth only requires taking on 7% more risk.

My friend Bob has a different way of putting this: “humans are lazy and weak unless they do differently.”

Frank Zappa said “progress is not possible without deviation.”

I’ve realized that one of the side-effects of my being a caregiver for so long has been latching on to workable routines with ferocious tenacity. When things are falling apart, finding something that works reliably, and then sticking to it religiously, offers salvation. This has made me disinclined to take risks at all, and my willingness to take them has plunged off a cliff in recent years.

Which is not to say that I haven’t had personal growth thrust upon me: the last half decade has kicked me in the ass in innumerable ways, and I am only now realizing the extent that I’ve emerged a changed person. Singed. But stronger. With a greater capacity to feel, a greater capacity to love, a greater awareness of my limitations and my strengths.

But this growth hasn’t been voluntary: it’s been the result of innumerable in-the-moment reactions to meltdowns and overdoses and broken hip sockets and ceaseless anxiety. Growth by a thousand cuts.

The notion of taking voluntary risks, risks that might have rewards attached to the other end, that’s something my muscles for which atrophied some time ago.

Having realized this, I found myself in need of a sudden burst of voluntary, uncharacteristic risk-taking.

So I signed up for the Bumble dating app.

The mere thought of doing so cause my stomach to twinge in a most unfamiliar way, something I recognized as nervous anticipation, and I figured that was a river I needed to follow if I was going to get to the base of 7% mountain.

The thing about Bumble is that it’s a closed warehouse that you can’t see inside unless you offer yourself up. Having been otherwise spoken-for since the early 1990s, I’d never seen inside the warehouse, and so some of the nervous anticipation was simply about the unknown.

Add that to what amounted to going on the not-entirely-private record as saying “okay, I’m single now,” and a possibly-imagined-but-very-real feeling that the world might think I’m meant to quietly mourn Catherine for the rest of my life, or at least another decade, and that’s a bountiful basket of risk.

What I found surprised me.

Not so much the swiping and the photos and the profiles, nor so much that a large proportion of the people Bumble first offered me up were friends of mine, or friends-of-friends, or sisters-of-friends (I do live on a small island, after all).

But rather that all of the prompts Bumble was giving me were about me. Prompts like “The quickest way to my heart is…” and “I’m hoping you…” and “What makes a relationship great is…”

It seems absurd to admit this, but this “tell me about yourself, and what you’re looking for” thing caught me unaware and completely unprepared to offer up cogent answers.

“How can I help?” (or its cousin “how can I keep you from being overwhelmed?”): that I’m good at; the idea that I would be allowed to have the agency to spell out my tastes in other people and other experiences, that was surprisingly novel.

I took a little griefy detour at this point: while, intellectually, I know that I’ve been a caregiver for a long time, in my heart of hearts that’s never rung completely true, and heretofore I couldn’t figure out why.

The reason why hit me over the head the other day, in the car while driving home from dropping off Oliver: my caregiving didn’t work. Catherine died. I didn’t prevent that. Therefore, what kind of caregiver could I possibly be other than a failed, good-for-nothing caregiver.

This makes no sense, of course, none at all. But the mind conjures up crazy shit and that’s what my mind was conjuring. Merely realizing this went a long way to allowing me to let it go.

With that realized–whew!–I was able to return to the notion of thinking about possible futures, my wants, my needs, etc. And that, man oh man, that is where the risky territory starts.

I got no idea.

So, I switched off my Bumble and I’ll hang out in this voyage of self-discovery part of the river of risk for awhile.

I gotta say, though: that butterfly-upside-down-cake roller coaster twist in my insides when I took a little risk, that was amazing, and gave me hope for what lies ahead.

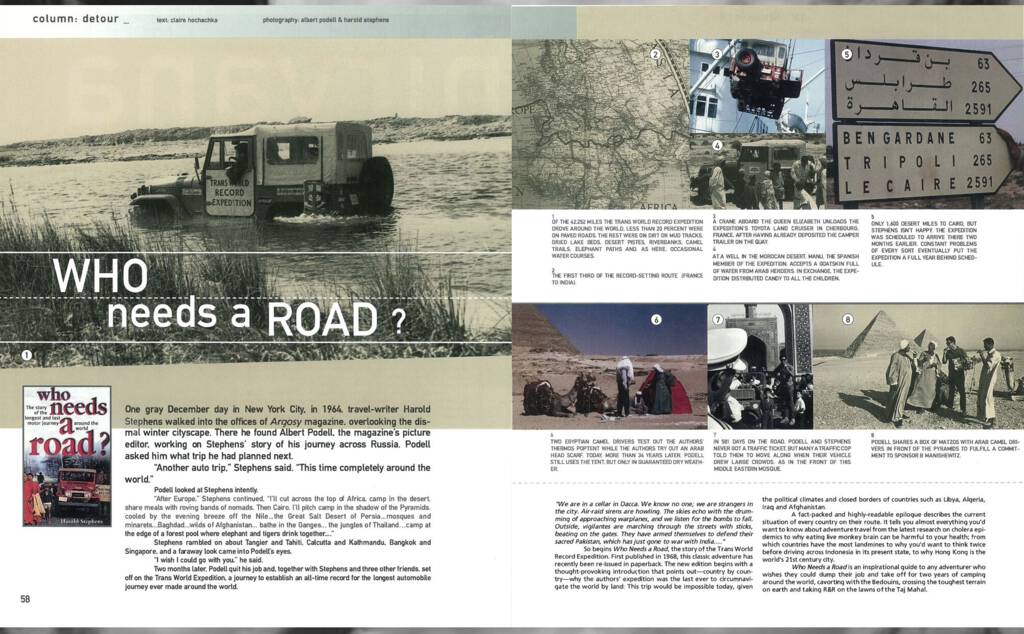

Twenty-two years ago, in the summer of 1999, I came across a copy of Blue magazine in a Boston bookstore. What drew me to purchase it, I don’t recall: I certainly wasn’t in the “adventure lifestyle” demographic it catered to. Inside that issue was a review of the book Who Needs a Road?, originally published in the late 1960s and re-issued in 1999:

I was intrigued, so I ordered a copy of the book and voraciously wolfed it down when it arrived.

The book chronicles the around-the-world trip, in a Toyota Land Cruiser, of authors Harold Stephens and Al Podell:

This book is about two men who wanted to drive around the world, to remote corners, to those places where few men have ventured before. They wanted to do it in a four-wheel drive, taking their own camper-trailer with them, to live at the edge of deserts and at the rim of tropical jungles, to drive the highest roads, and the lowest, to be free to make their own choices, and the Trans World Expedition was born. This is their incredible journey. That they did it, and how they did it is their tale told in this exciting book.

Toward the end of the book, as the expedition crossed over the Mexico-US border, came this scene:

We headed north toward the Rio Grande. After we cleared the Mexican customs and immigration posts, we drove onto the long bridge that connects Nueva Laredo, Mexico, with Laredo, Texas, USA. Home at last. Home. The U.S.A. After 19 months. Newsreel cameramen came racing down the bridge toward us. Chief Samuelson, the Toyota press agent, waved from the rail as he directed a photographer. And there was Asbury Nix from Trade Winds who’d flown down from Manawa (pop. 1,037) to welcome us back. And dozens of reporters. And a girlfriend of Al’s from San Antonio.

A Texas highway patrolman at a border checkpoint welcomed us hack to the States. For the first time, we had a smooth, safe, six-lane highway ahead of us. The end of the bridge. The brick customs house with our flag flying proudly above it. The Stars and Stripes fluttered in the autumn breeze. I didn’t think the sight would affect a seasoned old traveler, but I felt tears come to my eyes.

Reading that, I was curious to know if the newsreel footage of the drive over the Rio Grande had been preserved somewhere; I’m not sure why I was curious, but perhaps it had something to do with having lived, for a time, in El Paso, Texas, with a view over the river into Mexico.

The publisher’s email address was listed in the front matter of the book; on a lark I sent off an email, asking about the footage. To my surprise, a few days later I got a reply not from an anonymous “publisher,” but from Harold Stephens himself, writing from Bangkok:

I thank you for your interest in my motor trip around the world. It’s true, we did shoot close to 10,000 feet of 16mm color film. The Public Relation firm for Toyota Motors was an outfit called Chief Samuelson in LA. Samuelson processed the film and I got a chance to see some of it. I thought it was rather good, and ended up with less than a thousand feet to review, which I still have. Toyota was rapidly growing after our expedition, and the PR firm knew its days were numbered. They did lose out, and held on to the film. I have made several attempts to locate Chief Samuelson in LA but with no luck. Nor does Toyota in LA know about him.

What happened next is perhaps the signature example of why doing things on a lark, and taking risks, can pay off in unexpected ways.

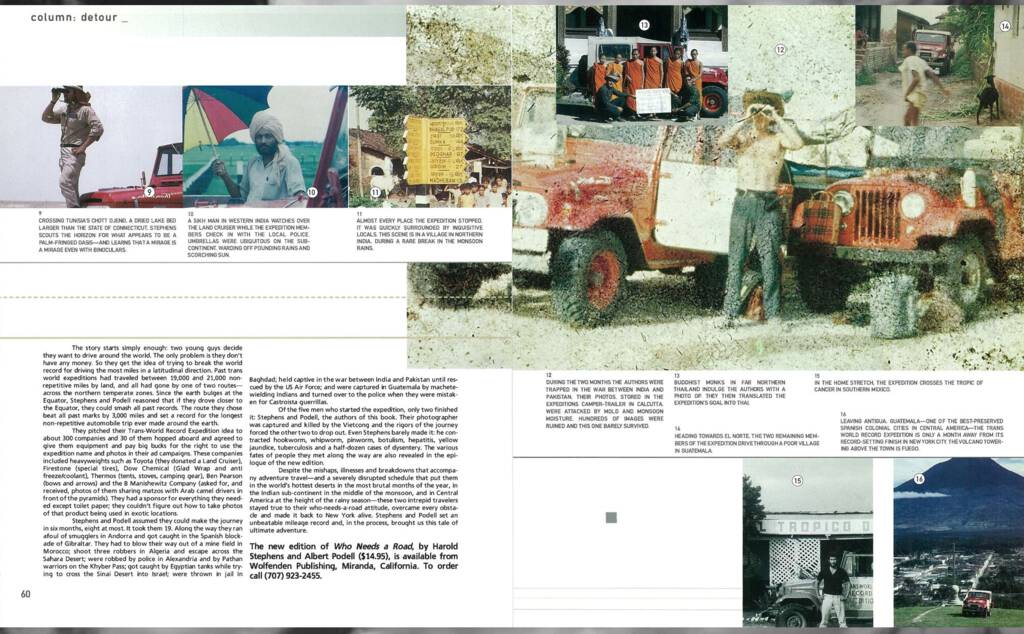

Harold and I struck up an email correspondence that lasted for the next 20 years. He gave me some clues about where I might find the footage mentioned in the book, pointing me toward press agent Chief Samuelson. And I set off on a months-long private detective-like jaunt to track him down, using skills I’d learned years earlier reading a book about “skip tracing.” Eventually I tracked his son down to Hot Springs, AK, where I found, from a helpful reference librarian, that he was working for the Garland County Sheriff’s Department. I tried and tried and tried to make contact: I left innumerable messages on answering machines, sent a letter, sent a FedEx, but never heard back.

Even though I’d failed in my quest, Steve–by this time I was calling Harold that, as his friends did–was impressed by my tenacity and research chops, and over the months and years to come he fed me a steady diet of cases to take on: a woman he’d dated in London after the war, a boat builder in Vancouver, fellow China Marines, an artist from Chicago who was with Huntley and Brinkley at NBC News in the mid-60s, the son of a Penn State anthropologist that Steve knew in Malaysia, relations of a man who was stabbed to death by Lana Turner’s daughter. It was all rollicking good fun, the kind of practical puzzle-solving I love.

In 2001, again on a lark, I sent Steve off an email suggesting that we might come and visit him in Bangkok. It was an absurd idea on many levels, none more so than that Oliver was just a year old at the time. But Catherine was game, and I figured it to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have a man on the ground in Bangkok. Which is how, 19 years ago this week, we found ourselves on the way to Thailand on a grand family adventure; among other things, the trip was the first of many times I used this blog to keep an online journal of our travels.

A few years later, Steve turned his tale of our visit into an article for the Thai Airways magazine, where he wrote, in part:

Let me tell you about Peter Rukavina from Canada who wrote and asked about travelling to Thailand with his wife and their three-year old son. Based upon other couples I saw around town, pushing kids in strollers, riding on buses and on the new Skytrain, and even on the fast-moving express boats on the Chao Phraya River, I told Peter and Catherine to come ahead. None of the parents I had seen seemed worried and the kids appeared to be happy. When I wrote to Peter I suggested travelling light and to bring a good-quality stroller.

I guess I never expected them to come. This often happens, people make plans and then their boss gets sick and they can’t get the time off or their grandmother ends up in the hospital. But not with Peter and Catherine, and their son Oliver. They were on their way and gave me their arrival information, and now I began to worry. Had I done the right thing? Here was a couple that had made only one trip outside of Canada, and that was to New York, a few hundred miles away. Now they were travelling half way around the world, so far away that if they travelled any farther they’d be on their way back home.

As it turned out, having Steve and his wife Michelle on the ground was invaluable: Steve met us at the airport, found us our first hotel in Bangkok, and gave us the kind of insider view of the country that only an expat travel writer could offer. They generously watched Oliver for a night so we could go out on our own, they took us to church with them, and they hosted a dinner for us on our last night in the country.

After that visit I continued to do dribs and drabs of work for Steve, some of it PI-like, some of it simple web work, like maintaining his personal website. Steve’s Land Cruiser trip around the world turned out to be one of scores of adventures he’d concocted over the years, fodder for a career as a travel writer: he befriended Marlon Brando in Tahiti, built and sailed a schooner around the South Pacific, investigated the disappearance of Jim Thompson. Steve always had something on the go; in 2004 he emailed me a slice of what was currently on the docket:

I am going to follow the Silk Road through Central Asia, do a jeep trip across China and Tibet, and sail all the rivers of Asia when my new boat is complete.

He invited me to join that Silk Road trip; I seriously considered doing so, but I wasn’t able to; I can’t recall whether he ever pulled it off.

I’d always hoped we’d get back to Thailand for another visit, or, baring that, that we’d be able to rendezvous with Steve and Michelle on one of their yearly trips to the United States. But we never did.

Some years back I created a Google Alert on Steve’s name; other than a lot of false positives–Harold Stephens turns out to be a pretty popular name–it never fed me news of Steve.

Until this week.

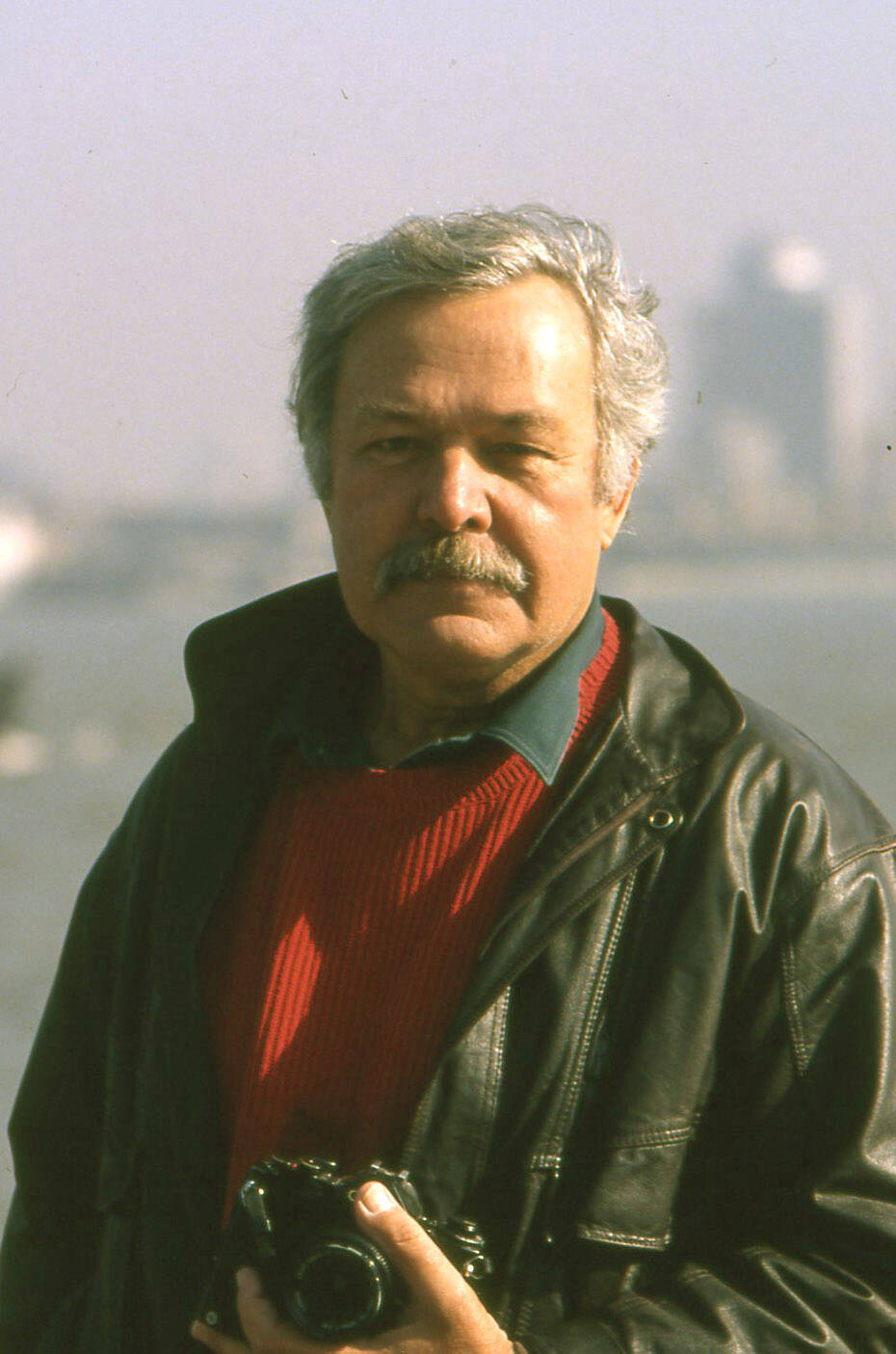

The article it led to in the Bangkok Post, by Roger Crutchley, let me know that Steve had died:

Someone who had just about been everywhere was travel writer Harold Stephens whom I’m sad to say passed away recently in Bangkok at the age of 93.

This was confirmed by posts elsewhere from Steve’s longtime collaborator Doug Ingold:

I learned today of the death of Harold Stephens, a business partner and a good and generous friend. Steve, as we all called him, died at his home in Bangkok in the company of his wife Michelle. Steve was a skilled and disciplined writer who lived the most adventurous life of anyone I ever met. And, amazingly, given his charisma, he was not a drunk, a blow-hard or an arrogant jerk, though at first, I will admit, I feared he might be all of those.

And from journalist Mort Rosenblum:

I last saw Steve in Bangkok. His shelves sagged under copies of his two dozen books. He’d written about 4,500 magazine and newspaper pieces. In his ‘80s, he was well-padded with Michelle’s cooking, and I figured he was done with the road. Sure.

At 93, he finally wangled a visa to travel with a friend across hermetic Myanmar, Burma, south to north. On the road, suspicious army officers locked them indefinitely in a foul tiny cell. His friend was terrified – of his captors and of Michelle in case the worst happened. Steve, meantime, was smiling. He had a story.

Of all the things I have to thank Harold Stephens for–and there are many–the most important one is the life of travel that he kicked off for us. That trip to Thailand started us off, and, let’s face it, once you’ve taken a 16 month old baby to Thailand, you can do anything; all the trips that followed were made better by the courage and confidence that we gained there.

Steve also showed me the value of travel writing, and that to become a travel writer all you really needed to do was to travel and then write about it.

And, beyond any of that, he was a friend.

Steve wrote this in the introduction to Who Needs a Road?:

The world opened to me when I was a young boy on a farm in Pennsylvania. It opened with books of adventure and travel, for those were the golden days when a young reporter named Lowell Thomas wrote about exotic places like Timbuktu and Kathmandu, and Richard Halliburton crossed the Alps on an elephant and swam the Bosporus. To me, these places and the lives these men led spelled romance. But when the real world came leaping at me, it was like the earth coming up to meet a skydiver. There was no casual introduction; it came up suddenly-with World War II.

It is tempting to point to Steve’s death as the end of an era, and in a way it is. But his writing, and his life force, inspired and motivated many who followed in his footsteps–I know, as I tracked down and talked to many of them over the years.

So the roads, or lack thereof, that Steve travelled are still there waiting for all of us to follow.

Goodbye my friend; I will miss you.

The cross-platform synergasm that is Modern Love—at last count it’s a newspapers column, a podcast, a TV series, and a book—is interesting in all its guises. My favourite branch on the tree, though, are the opening titles to the TV show; they just plain make me happy and hopeful every time I watch.

Also on the topic of love, Home, from Imelda May, does not fail to bring tears to my eyes, for reasons of both sadness and joy.

My copy arrived today. I bought it 100% based on the title, and even if it’s a useless book, the title itself provides words to live by that will outlast it.

We’ve had a microwave at 100 Prince Street for a few months now, a loan from one of Oliver’s support workers. I’m pretty sure Catherine is turning over in her grave, as I maintained an unbroken record of steely microwave opposition over our 28 years together.

In the end it took our physicist friends and their patient explanation of how microwaves work (it’s not magic, it’s water molecule vibration!) to give me the push I needed.

I still haven’t fully integrated the microwave into my culinary regime, but I have discovered some very handy uses:

- I bought a Magic Bag (a fabric bag filled with oats, in essence) and warming it up in the microwave is just the ticket for typing-ravaged shoulder muscles. This has been the killer app.

- Blasting hotdog buns for 30 seconds after taking them out of the fridge revivifies them into fluffy like-new condition.

- Cooking potatoes for 5 minutes before grating them results in much-improved potato latkes.

- I can turn frozen berries into compote, ready for the waffles, in 45 seconds.

- Oliver’s been heating up leftovers for lunch; the UX and auto-shutoff of the microwave is much better than using the stove for this.

So far there’s only been one minor explosion: I over-reheated a piece of chickpea and squash pie and the chickpeas exploded. Live and learn.

I truly feel like I’m resident in the Better Living Centre at the Canadian National Exhibition in 1977.

I am

I am