The latest to come out of the Island Lives project is a history of Prince Street School, a printed version of a 1961 address to the Prince Street Home and School Association by the school’s Principal Mabel Matheson. In her introduction:

This venerable structure is impregnated with the extraordinary qualities of mind and spirit possessed by the host of inestimable students and teachers who have given of their talents unstintingly to this school during the past 90 years, and so it has acquired a personality all its own.

It’s hard to imagine anyone delivering a 30-page address to a Home and School meeting these days, but we’re lucky she did, as it’s an invaluable capsule history of the school.

A Love Divided – The tale of a 1950s Irish marriage pulled apart by religion, and the resulting pulling apart of the community on religious lines. Based on actual events. Stars the inimitable Orla Brady in the lead role, and a cast of others you’ll recognize from Ballykissangel if you’re a fan. Three DVD copies available from the PEI Provincial Library.

Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles – The story of a Japanese man estranged from his son who travels to China to videotape a folk opera in an attempt to form a parental bond. In Japanese and Chinese with English subtitles. Very well acted, and a surprisingly powerful story. Stunning scenery. Available from the PEI Provincial Library on DVD.

Four years ago I buckled and decided to follow Catherine’s “here what I want for Christmas” instructions rather than improvising. I think it was the previous year’s “puffy coat” gift that pushed things over the edge.

And so Catherine got an espresso machine for Christmas, a nice Gaggia Coffee model that, at least relative to the cheap Consumers Distributing models we’d had before, is built like a tank.

I ordered the machine at the very last minute from Espressotec in Vancouver: they raised heaven and earth to get it to Charlottetown for Christmas, and were very helpful at every step of the way (I wasn’t a coffee drinker at the time and never had been, so they did a lot of hand-holding on model selection).

After four years of vigorous use, and after being dropped a few times, the plastic handle that holds the “portafilter basket” (aka “the thingy that holds the coffee”) finally disintegrated. A quick call to Espressotec revealed the proper replacement handle and 24 hours later it was making its way to Charlottetown.

The Gaggia makes nice coffee, is easy to operate, and Espressotec is, from the evidence, a good company to deal with. If you’re ready to upgrade the coffee infrastructure in your house, I recommend them.

Now that we’ve passed the event horizon here in Prince Edward Island, from the unfettered Lord’s Day capitalism of May to December and into the dark wastelands of January to May mandatory Sunday shuttering, Sunday shopping discussion is back in the air – blog, blog, letter, letter – and almost all of it falls into the traditional two camps of libertarian “government has no place regulating business” and the spiritual “God set aside a day of worship.”

Neither argument is particularly compelling – mandatory religion is about as distasteful as mandatory capitalism – and I propose that if we’re going to tinker with the week we go all-in and take a serious look at how we collectively arrange our time.

Here’s my idea, admittedly custom-tailored to my personal work preferences: smooth out the week.

Take the standard work week down to 35 hours, and have everyone work 5 hours every day, 7 days a week. We’d have to hash out the slice of the day we’d devote to work – I’d suggest 7:00 a.m. to Noon, but I’m okay getting up early. Retail store hours could follow on by an hour or two – say from 9:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. – to give working people a chance to get some shopping done. Restaurants, hospitals, snowplows, etc. would continue on their “open all the time” tack.

There are several upsides to this changed system:

- No bias to Christian religions: every religion that has a sacred day has a good chunk of it to worship.

- More work and school productivity. Nobody gets any work done on Friday afternoons right now, and a good part of Monday at schools is spent getting students back into a learning frame of mind. With no large two-day gap to overcome, we all become more productive at home and at school.

- Lots of family time. I don’t know about you, but with supper at 6 and room for a bedtime story and teeth brushing, regular weekdays leave about 30 minutes for quality family time. If we all got home for lunch and had the rest of the day free, there would be untold opportunities for family fun.

- Time for daily personal activities (in daylight!). I think most people are ”working for the weekend” right now, and have very little time available for recreation, fitness, reading, whatever. Open up the afternoons and when not playing Snakes and Ladders with the kids we could be learning how to snowboard or reading War and Peace.

- Week-long shopping. The capitalists get their opportunity to sell things all week long.

It’s possible that there are very good reasons that this idea won’t fly. But at least considering it takes us out of the tyranny of the religion vs. capitalism debate and onto some creative exploration much more substantial rearrangements of our collective timetable.

Comments welcome.

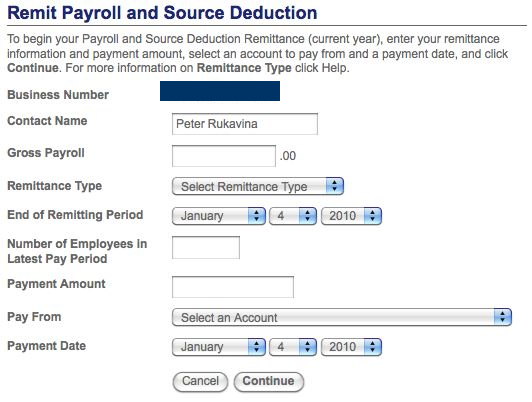

Regular readers will recall that the bane of my corporate existence is the monthly payroll remittances required to the Canada Revenue Agency. They’re the one government payment that comes with a draconian penalty for late filing, and it seems that at least once I year I get stung.

But no more!

It’s now possible to make the remittance completely digitally through the Metro Credit Union website: just click “Business Tax Payments,” enter your business number, and then click “Remit” and enter the same details you usually fill in on the printed form:

Life will never be the same.

Eight years ago, in the winter of 2002, [[Catherine]], [[Oliver]] and I spent two weeks in Thailand. The nominal purpose of our visit was to visit my friend Harold Stephens, but we got to see a fair bit of the country too, and spent a few days in Chiang Mai in the north.

The backbone of the public transit system in Chiang Mai are the songtaos. These are covered pickup trucks with wooden benches on either side, and if you want to get around the city you’ll inevitably end up in one. As did we:

When I think of that time, and look at the picture, the “purchase the most secure child restraint on the market” version of me cringes: there we are speeding down the streets of Chiang Mai with nothing holding Oliver in that my one-handed grip (I had to hold on to the truck with my other hand to avoid falling out).

It seems, well, crazy.

Except at the time, it didn’t. It seemed completely rational.

I’m not sure how to explain this.

Without advocating that we throw away common sense while traveling, it does seem to suggest that travel can take us into unexpected situations and make us do unexpected things. Different things. Things that at home don’t make any sense at all. Things that, when we get home and look back, make even less sense.

Of course this would be a different story if Oliver had fallen out of my arms and under a tuk-tuk.

But he didn’t. And we survived. And the trip, in many small ways, changed our life for the better.

Somewhere buried in there is a lesson to be learned about the virtues of travel.

Some video I streamed from the 2010 levees:

- Lieutenant Governor: Lovely music. His honour reads my blog.

- City of Charlottetown: Where did the sandwiches go? Met Deputy Mayor Stu MacFadyen.

- HMCS Queen Charlottetown: Busiest levee of the day. Very tasty chowder. Odd fantasy life where they pretend it’s actually a boat (“welcome aboard!”).

- Haviland Club: Top-flight sweets. Most grounded crowd of the day.

- Queen Charlotte Armories: Once again the band was fantastic. And the museum interesting.

- Diocese of Charlottetown: The full buffet of yore replaced with tiny slices of fruitcake, and the crowd crammed into the hallway. Bishop was friendly, though.

- Hon. Robert Ghiz: No sandwiches here either, but still the best food of the day. Premier was in top form.

Here’s is the 2010 levee schedule for January 1, 2010 for Charlottetown and area. If you’re new to all of this and want to give it a try, read How to Levee. And if I’ve missed anything, please leave a comment.

Update on Dec. 31, 2009: All times are now confirmed. See comments for notes about changes from original. Also added:

| THE LEVEE OF… | HELD AT… | STARTS | ENDS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell Webster | Timothy’s World Coffee | 9:00 a.m. | 10:00 a.m. |

| Lieutenant Governor | Fanningbank (Government House) | 10:00 a.m. | 11:30 a.m. |

| City of Charlottetown | Charlottetown City Hall | 10:30 a.m. | 12:00 Noon |

| Canoe Cove Community Association | Old Canoe Cove Schoolhouse | 10:00 a.m. | 2:00 p.m. |

| University of PEI | McDougall Hall (at UPEI) | 11:00 a.m. | 12:30 p.m. |

| HMCS Queen Charlotte | 10 Water Street Parkway | 11:30 p.m. | 1:00 p.m. |

| Haviland Club | 2 Haviland Street | 11:30 a.m. | 12:30 p.m. |

| Town of Stratford | Stratford Town Centre | 12:00 Noon | 1:30 p.m. |

| Queen Charlotte Armouries | Foot of Haviland | 12:30 p.m. | 1:30 p.m. |

| Seniors Active Living Centre | CARI Pool Building | 12:30 p.m. | 2:00 p.m. |

| Masonic Temple | 204 Hillsborough St. | 1:30 p.m. | 3:00 p.m. |

| Diocese of Charlottetown | Basicila Rectory (Bishop’s Palace) | 1:30 p.m. | 2:30 p.m. |

| Town of Cornwall | Cornwall Town Hall | 1:30 p.m. | 3:00 p.m. |

| Royal Canadian Legion | 99 Pownal Street | 2:00 p.m. | 3:00 p.m. |

| Benevolent Irish Society | 582 North River Road | 3:00 p.m. | 5:00 p.m. |

| Premier Robert Ghiz | Confederation Centre of the Arts | 3:00 p.m. | 5:00 p.m. |

| Charlottetown Curling Club | 241 Euston Street | 4:00 p.m. | 6:00 p.m. |

| Charlottetown Firemen’s Club (Dance) | Charlottetown Fire Hall | 6:00 p.m. | onwards |

I am

I am