Several people have asked me what I think about Apple’s newly-announced iPad.

While there’s no doubting it’s a significant technical and design achievement, and is filled with the usual Apple lusciousness, the iPad scares me, and why it scares me is well-expressed in the blog post Is the iPad the harbinger of doom for personal computing?, the heart of which is this:

The fundamental difference between a Mac and an iPhone is that I can run any software I want on my Mac. I can buy it on a DVD, I can download it from the Internet, or I can compile it myself. I can get rid of OS X and install another operating system. The Mac is a general purpose computer in the classic sense. The iPhone is not.

Apple decides which software I can run on my iPhone. Apple provides the only means by which I can get it. The platform is for all intents and purposes, closed, and the hardware is closed as well. Sure, the iPhone is great to use, but the price of using it is that you’re rewarding Apple’s choice to bet on closed platforms.

What bothers me is that in terms of openness, the iPad is the same as the iPhone, but in terms of form factor, the iPad is essentially a general purpose computer. So it strikes me as a sort of Trojan horse that acculturates users to closed platforms as a viable alternative to open platforms, and not just when it comes to phones (which are closed pretty much across the board). The question we must ask ourselves as computer users is whether the tradeoff in freedom we make to enjoy Apple’s superior user experience is worth it.

I agree completely.

I don’t want the spirit of the digital devices in my life to become more iPhone-like, especially the devices at the heart of my digital nervous system; the prospect of owning an iPad seems awfully like buying a pair of exquisitely-design shoes that can only be shined, re-laced or repaired by sending them off to the manufacturer.

The iPad, like the iPhone and the iPod touch, represent another step down the road toward Internet devices being kneecapped into a conduit for us to passively pay for and consume tightly controlled and regulated content.

The power of the net for me has always rested in its utility as a vehicle for freely producing, sharing, mashing-up and distributing stuff, not in its utility for allowing me to watch re-runs of LOST more easily. While there’s no doubt that the iPad is a sleek device to enable the later, it fails abjectly as a device for the former, and if anything it has me thinking it might be time to sell the MacBook and invest in a more open solution for my desktop before it too falls prey to this emerging ethos.

I watched this Ricky Gervais movie over lunch today (it’s on Eastlink’s Video on Demand service in you’re a customer). With the proviso that I’m a big sucker for contemporary reality-turned-upside-down movies (it’s not for nothing that I loved Heaven Can Wait), I heartily recommend it: Gervais puts in a nice performance, as does Jennifer Garner. The only weak point was Jonah Hill, who seems like he had a much bigger part in the film at some point, most of which ended up on the cutting-room floor.

I’m not sure how I came to first know Bruce MacNaughton, but then again it’s hard to live on Prince Edward Island and not know Bruce. Among other things he has founded the erstwhile Perfect Cup Café in Charlottetown (where Leonhard’s is now), the erstwhile Piece a Cake restaurant (above the PEI Company Store), the erstwhile Marketplace (in the former Woolworth’s) and, most notably, the (very much alive) Prince Edward Island Preserve Company in New Glasgow, Prince Edward Island.

Bruce’s business sensibility is one I greatly admire: when Bruce says he’s “not in business to make money,” it’s more than a throw-away line, it’s at the core of how he operates (sometimes to his detriment, as the string of erstwhiles demonstrates…).

A few weeks ago Bruce suggested we have coffee; he wrote “I would like to discuss what we might do; could do, shouldn’t do online.”

And so we met on a chilly Tuesday morning at Casa Mia and Bruce bought me an espresso and we talked about, well, almost everything but the “online” thing. Okay, that’s not completely true: we did touch briefly on his new website, and what he might do with 11,000 email addresses he’s collected over the years but never emailed to, and other onlinely things. But we also talked a lot about sugar content and customer service, and customs regulations.

What emerged from our conversation was the notion visiting the Preserve Company in New Glasgow is, for many people, a singular experience, and Bruce’s interest in finding out whether it’s possible to build on that experience after the fact. Not (necessarily) to sell stuff, but for a host of other reasons, most of them intangible.

One of the things I admire about Bruce is that he is transparent and honest about doing business: if you have a bad experience at Bruce’s place, and email him, it’s likely that a few hours later Bruce will have emailed you back, apologized, and turned a bad experience into a surprising one.

Extending from this notion, and a strong desire on my part to avoid any hint of “developing a social media marketing plan,” I suggested to Bruce that, at least to begin, we keep the conversation going. But in public.

And so this Tuesday morning we met again at Casa Mia, but this time with a video camera. I pressed “record” and we talked. We’ll do it again next Tuesday.

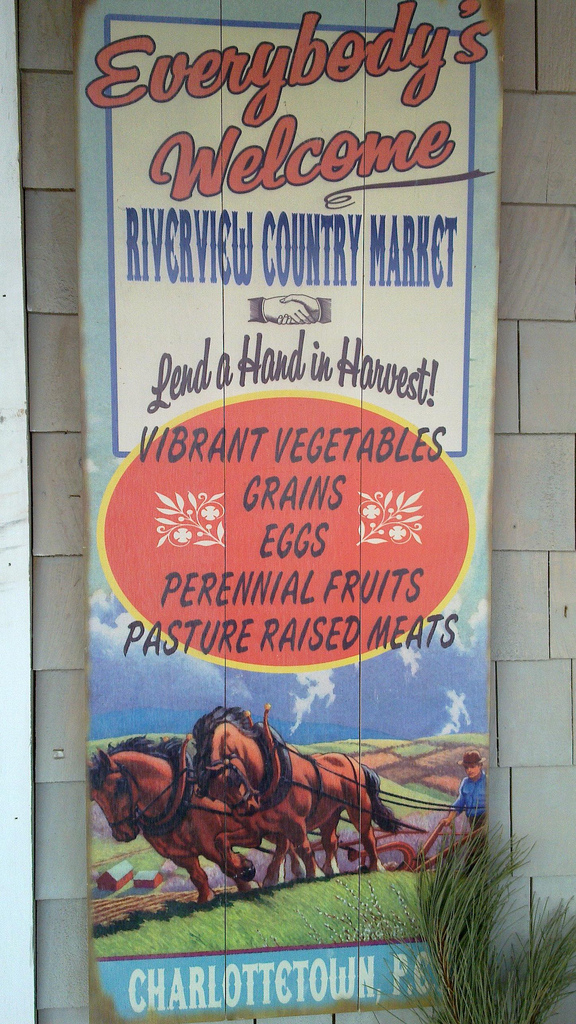

I’d been hearing about Riverview Country Market from friends for a while now, but it wasn’t until yesterday that I managed to visit.

Wow.

I hadn’t made a point to rush over earlier because everyone talked about the meat counter and how great it was. But I eat less meat than, well, just about anything, and so that’s been of little interest to me.

But there’s more to the place than just the meat: they sell local produce (including potatoes and apples with their varieties labeled, which is just common sense but novel nonetheless), local preserves, local baking, and a smattering of non-local things like lemons to round things out.

It’s all laid out in a compact but efficient little space with friendly staff and good music.

If you lament the loss of bestofpei, another place that focused on local but that went out of business in the fall, take heart, as Riverview is everything that bestofpei should have aspired to be: well-stocked, focused, and without a hint of pretense.

The only downside is that they’re located, for all intents and purposes, “out of town,” being way out there in the wastelands of Riverside Drive (it’s only a 20 minute walk from our place, but it’s a harsh and unforgiving 20 minute walk through pedestrian-unfriendly terrain).

If these folks took over the Clover Farm in on Queen Street they would completely transform the grocery landscape for we downtowners; as it is, I’ll become as regular a customer as their location allows, and I encourage you to drop by and check them out if you haven’t yet.

Back in 2008, Aliant, the local brand of the Bell Canada telephone company, did a deal with the Province of Prince Edward Island: Aliant got to renew its communications contract with the province and in return agreed to “extend broadband services to every community in Prince Edward Island.”

In December of 2009 Aliant announced “Mission Accomplished” and published a press release titled, in part, “PEI broadband infrastructure build complete.” But over the year somehow “every community in Prince Edward Island” in the province’s original announcement had morphed into “virtually all areas of the Island” in Aliant’s.

And then, in late December, came the fine print that fleshed out the difference between “every” and “virtually all:” rather than actually installing wired broadband to every home in the Province, Aliant was opting out of the difficult bits and using its wireless cellular network-based Internet service as a sop to customers where they didn’t want to extend the wired network.

There’s been a lot of media coverage about this, culminating in a public meeting in the eastern part of the province last night where Aliant made some pricing and data cap adjustments to the wireless service to try and distract the wrath of the under-served.

What’s been largely missing in the media coverage and related discussion of this issue, however, is that Aliant is not living up to the spirit of their original agreement.

Yes, wireless Internet is “high speed” in the sense that it’s faster than dial-up.

But it’s not “broadband infrastructure.”

If it was, then Aliant wouldn’t have wasted all that money installing DSL for everyone and would have just mailed out “turbo sticks” – its wireless access dongle – to all Islanders.

Broadband infrastructure Island-wide means that I should be able to run an Internet-based business in North Lake as easily as I can in Charlottetown. It means static IP addresses, the ability to scale bandwidth as my business grows, service-level agreements.

It doesn’t (just) mean the ability to watch YouTube.

And while Aliant might have tricky euphemisms for why it’s not installing actual broadband infrastructure, if it were being honest it would simply admit that it doesn’t want to pay for it.

There’s no technical reason why absolutely every home on Prince Edward Island can’t be provided with actual wired broadband service.

There’s nothing different about the soil or the air currents or the angle of the sun in Eastern Kings that makes installing broadband there any different than in downtown Charlottetown.

It’s just requires additional investment. Investment that, apparently, Aliant believes it can dance its way out of.

All of which would be fine if Aliant were simply another Internet company making its way in a competitive marketplace.

But it’s not: it made a deal with the people of PEI. A sole-sourced deal that was allowed because of its “regional development benefits.”

I have no issue with the original deal: government used its power in the marketplace to extract benefits to Islanders at not additional costs to taxpayers. That was wise and frugal.

But if we really believe in “One Island Community, One Island Future,” we can’t let Aliant get away with this: if an Islander is an Islander is an Islander, and we’re going to commit to equal access to the network for all, then we need to call Aliant on its bluff and demand that it do the honourable thing, and make the investment it committed to, letter and spirit.

So I’m the proud owner of a new Nokia N900 phone and after a few years on a highly-evolved version of Nokia’s Symbian operating system (on my N70 and later my N95), it feels like starting over all over again: while the Maemo operating system on the N900 has gone through several iterations, it’s still not completely ready for prime time, at least in its current state on the N900, so I’m left to fill in some gaps.

One of the holes is syncing contacts and calendar with a Mac. With the N70 and the N95 I just used the iSync plug-ins that Nokia built and all was well. There’s no iSync plug-in for the N900 yet (there are rumors of one coming), so I needed a workaround.

Fortunately the N900 does support syncing with other Nokia devices, and as I still have my N95 around, this proved to be the solution for the time-being. Here’s what I did:

- Ran iSync on my Mac to sync contacts and calendar on my Mac with my N95.

- On the N900 opened the Contacts application, then selected “Get Contacts” from the menu and “Synchronise from other device,” selected my N95, and left the sync to happen.

About 5 minutes later my N900 was populated with all my Mac’s contacts and calendar items.

Not something I want to keep doing forever, but at least it works.

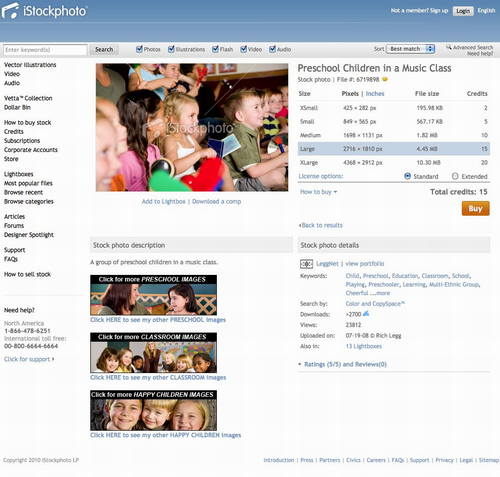

There was something about the children pictured in the photo attached to this CBC story about Kindergarten registration that made me think “those don’t look like real Prince Edward Island children.”

I’m not sure what it was – were they too happy? sitting too attentively? equipped with unusual musical instruments? – but it turns out I was right: the children are generic Preschool Children in a Music Class from iStockphoto:

As such, I’m not sure what editorial role the photo plays.

Kudos to TinEye: it was their tool I used to get to the bottom of this. You’ll find the same children also gracing the front page of the Best Evidence Encylopaedia in the UK.

A rather remarkable thing happened on Thursday night.

At the bimonthly meeting of the PEI Home and School Federation one of the items on the agenda was discussion of what to do with about $4,000 of “parent engagement” funding that had so far been unspent. There was a suggestion that the money be used to purchase parent-focused resource materials for public school libraries; but when we did the math – $4,000 divided by about 50 schools – we realized that $80 per school wasn’t going to buy too many resources.

So I suggested that instead of trying to equip every school library with a tiny collection of resource we instead give the money to the Public Library Service to use to purchase a province-wide collection of parent resource materials. While $4,000 isn’t a huge amount of money, in clever hands it can purchase a good collection of resources, and because the Library Service has a presence across the province, and because resources can be delivered, on request, to any branch, the reach of such a collection would be much greater.

My fellow directors agreed – it turns out we have some library workers on our board who said there was no reason it couldn’t work – and so we passed a resolution to go ahead.

Now while this makes perfect sense, it’s remarkable because it’s such a rare occurrence: I’m sure there are literally dozens of tiny resource collections squirreled away in the offices of non-profit organizations across the province. Organization gets funding from ACOA to develop a resource collection; hires resource coordinator; buys resources; funding runs out; resource collection gathers dust in the corner: I’ve seen it happen over and over, and have been party to it more than once.

And yet there’s the Public Library Service: a presence across the province, convenient hours, friendly staff, an online catalogue, a reservations service – in other words everything you need to provide equitable, low-barrier access to resources for all Islanders. The perfect repository for public resources.

The Office of Energy Efficiency leveraged this notion to distribute home electric meters. There’s no reason why any organization couldn’t use the same sensibility to house their own special-purpose collections of books, DVDs, skateboards, solar lawnmowers or darning needles.

Kudos to my home and school colleagues for having the imagination to see that sometimes it makes more sense to work collectively than to build tiny little information islands.

I am

I am