Some time ago I came across a letterpress hack from the 1890s:

Today I had cause to consider setting the Portuguese name Patrícia in metal type (note carefully: that’s a lower-case “i” with an acute accent over it) and as I only have fonts of English and French, I lack the required accented letter and so was force to apply the aforementioned “thought and ingenuity.” The result was this:

The acute accent is a comma set on the line above; I set this in upper case because it conveniently allowed me to avoid a conflict between the dot over the “i” and the accent). This might not be the best typeface for this, as the comma is more stylized than I’d like and a simple stroke would work better. But it’s a start.

Since I started experimenting with visualizing Prince Edward Island energy information over a year ago, one of the most important pieces missing from the data puzzle has been Island’s “load” — what the province calls “the amount of electricity required to power lights, motors, appliances and other users of electric energy in PEI.”

So, in other words, “how much electricity we 140,000-odd people (and our machines) are using.”

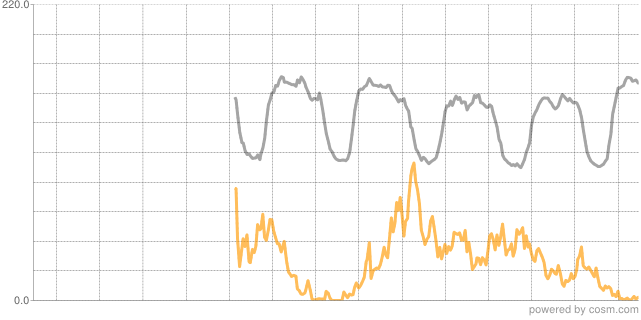

But last week the province started publishing that figure in near-real-time and so now we can generate graphs like this one, showing the load over the past 5 days (you might very well ask “what the heck is using 100MW of electricity in the middle of the night?” and I’ve posed that question to Maritime Electric and await an answer):

)

Now that we have that “total load” number, we can compare it to the “how much wind energy are we generating on the Island right now” figure, and so get a near-real-time percentage figure that looks like this for the past three hours:

)

(As I write this the figure is 1.26%, in part because there’s not a lot of wind blowing today and the load, at 162MW, is high).

Overlaying the wind energy generated (orange) on top of the load (black) for the past five days, you can see that once during that period (around midnight on June 23) we came really, really close to meeting 100% of our load with wind energy:

(Cosm doesn’t have the ability — I don’t think — to generate graphs with two data values, so I grabbed these individual graphs and combined them together myself manually).

The logical next step here is to create a physical device that I can place on my desk — a siren? an LED slider? a VU-meter? — that will offer instant feedback about what the current percentage figure is.

Note: in my calculations I’m using the figure for wind energy generated on PEI, regardless of whether it’s being generated to meet an export contract; like the province says, “usually all electricity generated in PEI remains on-Island,” which is to say that the electrons stay on the Island, even if the dollars come from elsewhere.

I’ve just pulled the trigger on what promises to be a fun multi-city obstacle course through Europe for July.

I call it the “visit almost everyone I know on that side of the ocean in 24 days” trip.

The kind of trip that would drive Catherine crazy with the “wait, you’re taking a train for four hours just so you can have lunch with someone!?” of it all. So I’m doing it solo (Catherine and Oliver are visiting family in Ontario, so it’s not like they’ll be pining for me at home in the hot summer sun).

On July 3 I fly from Halifax to Frankfurt ($402, taxes and fees included, on Condor) where I hope to be able to have a quick visit with Ali.

Then it’s off to nearby Mainz for a pilgrimage to the Gutenberg Museum.

On July 6 I’ll head up to Düsseldorf to visit Pedro and Patrícia (who I’ve been trying and failing to visit since our aborted ships-crossing-in-the-night visit in 2010). And maybe João too?

Two days later it’s up to the Netherlands to Enschede to see Ton and Elmine for a couple of days, and then across northern Germany for a brief anti-respite in Berlin where I’ll spend three days at Betahaus doing so actual income-generating work, hopefully leaving some time to see my panoply of Berlin friends and to visit the usual haunts and find some new ones.

On July 13 it’s up to Malmö, Sweden by way of Copenhagen for what appears to be my now-annual visit to Luisa, Olle, Jonas and Morgan. And, if I’m lucky, also to be able to see Henriette and Thomas and Penny. And who knows who else?

On July 18 I’ll fly across Europe to Kiev (142 EUR all-in on Air Baltic) where I’ll meet up with family for my first visit to Ukraine, including a pilgrimage to the потягайло home place around the town of Horodenka).

On July 26 it’s back to Halifax via Frankfurt (somewhat inexplicably given how cheap it was to get there, $1105, all-in on Condor).

Given that seven years ago, when I made my first friend in Europe, I was starting from a blank slate, not knowing a single soul, to have such a diverse community there today means that my grand multi-year European experiment must be working. I’m quite looking forward to it.

A handy new feature of Google Voice: if I get a voicemail message there’s now the option to embed it in a web page. Like this 3-second voicemail, origin unknown, that I got this morning:

The message got automatically machine-transcribed by Google Voice as “Unfortunately, I don’t feel like.” Which means either Google Voice has better ears than I do — I can’t make out any words — or that it just took a wild guess.

I got a call from Google Engage yesterday that went to voicemail and was transcribed as follows:

Hello Peter, My name is anyway. Duke’ll would engage agencies. I was calling to be about your membership google blondie. And the package that was made. If you have a phone inside of the mouse and Ten coupons. Gorgeous golden coupons. I was hoping to get some feedback from you. Just wanna follow up and answer any questions you may have about the use of the coupon. If there’s anything we can do. I think we can decide to go to a customer base. Please let me know. If you need to ask for a client those complaints everything off. Rex, or did agency scene. The can walk into the computer is set up the dumping.

Listening to the audio, she actually did say “gorgeous golden coupons” but almost everything else was mis-transcribed.

My Golding Jobber No. 8 letterpress came without a brake pad, so I’d been running it without brakes since I started using it, which made for the awkward need to slow down the flywheel with the palm of my hand. I resolved to solve this problem yesterday: I bought a $6 piece of leather from Michaels (Tandy brand!), cut down a piece of wooden furniture to fit the brake pad holder, and affixed the leather to the wood. Here’s the result:

And here’s the result in action:

Regular readers may recall my efforts, starting over a year ago, to have open data about Prince Edward Island electricity load and generation released.

I’m happy to report that the Province of Prince Edward Island has now, at long last, made this available, both in human-readable form with pretty charts and as JSON-formatted raw data.

To grab the raw data, point your clients at this JSON and you’ll get back something like this:

[

{

data1: 152.13,

data2: 25.58,

data3: 0,

data4: 23.3,

data5: 2.28,

updateDate: 1340234042,

error: 0

}

]

The values returned are as follows (with explanations courtesy of here):

- data1 is Total On-Island Load — the amount of electricity required to power lights, motors, appliances and other users of electric energy in PEI.

- data2 is Total On-Island Wind Generated — the amount of electricity being generated from all wind facilities in the province.

- data3 is Total On-Island Fossil Fueled Generation — the amount of electricity being generated from oil fired equipment. Typically, this generation is only required when there is an interruption of supply from off Island.

- data4 is Wind Power Used On-Island — only that portion of the Total Wind Generated that is being used to meet purchase agreements of the province’s two electrical utilities, Maritime Electric Company, Limited (MECL) and City of Summerside Electric Utility.

- data5 is Wind Power Exported Off-Island — that portion of wind generation that is supplying contracts elsewhere. The actual electricity from this portion of wind generation may stay within PEI but is satisfying a contractual arrangement in another jurisdiction.

- updateDate is the unixtime the data was updated (I’m not sure of the schedule, but it’s not real time data).

- error — I presume this is some sort of error code, but in my experience it’s always been zero (0).

Based on the work I did with Pachube (now Cosm) last year, I’ve created a Cosm Feed for the data, fed by a PHP script that grabs the data and reformats it into either more readable JSON, XML or the Cosm datastream format.

While we wait around for Maritime Electric or others to enable the “smart grid,” this data can be used, right now, to build intelligence on a DIY level.

Pull the data from the Cosm feeds for on-island-wind and on-island-load, compare the two, and generate an RSS feed item if the wind generation exceeds the load (meaning we’re getting ALL of our energy from the wind); feed the RSS feed to If This Then That and then build a recipe that turns a Belkin WeMo switch on to make you coffee: voila, you’ve got always-wind-powered-coffee.

The Province is to be lauded for this effort, especially for making the data available in JSON so that it can be re-used elsewhere; it’s a fantastic development, and a nice complement to Prince Edward Island’s Wind Energy Strategy.

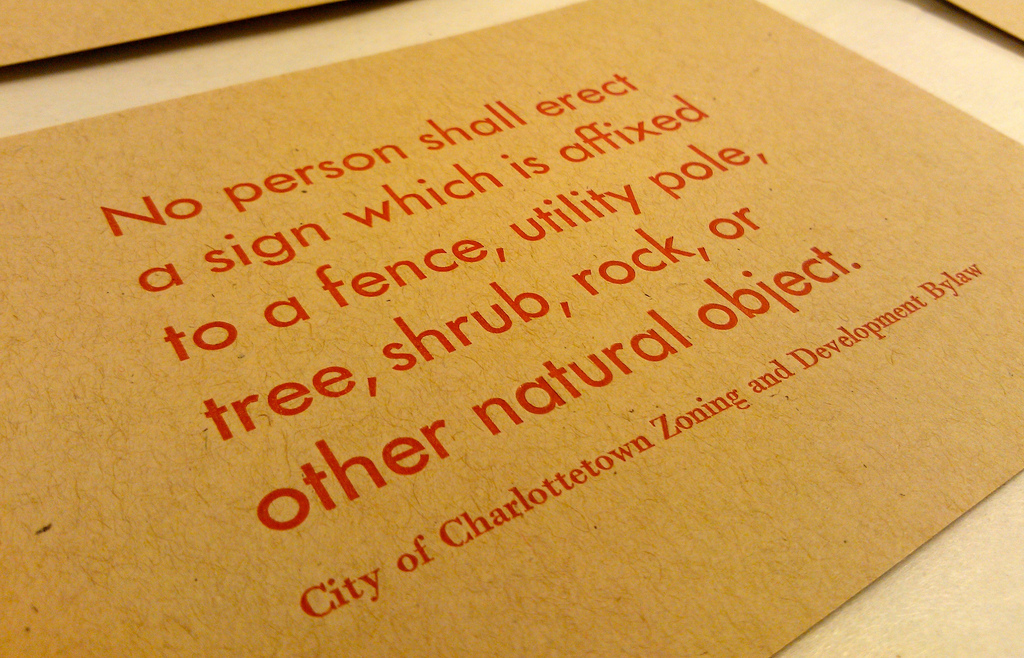

This afternoon I printed up a sort of “do it yourself civil disobedience kit” with an excerpt from the City of Charlottetown’s Zoning and Development Bylaw: an excerpt from its section on signage, which places rather inflexible limits on our constitutionally-guaranteed right to “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.”

Regular readers will recall that this very issue was the topic considered in the 1993 Supreme Court of Canada case Ramsden v. Peterborough (City) where the court said, of the City of Peterborough, Ontario bylaw of the day, in part:

It is clear that the effect of the by-law is to limit expression. The absolute prohibition of postering on public property prevents the communication of political, cultural and artistic messages.

The Peterborough bylaw’s wording was:

No bill, poster, sign or other advertisement of any nature whatsoever shall be placed on or caused to be placed on any public property or placed on or attached to or caused to be placed or attached to any tree situate on any public property within the limits of the City of Peterborough or any pole, post, stanchion or other object which is used for the purpose of carrying the transmission lines of any telephone, telegraph or electric power company situate on any public property within the limits of the City of Peterborough.

In other words, much the same as we have today here in Charlottetown, albeit without the prohibition on affixing signs to shrubs, rocks and other natural objects we enjoy.

The Court cited another case, Committee for the Commonwealth of Canada v. Canada, and in that ruling Justice Claire L’Heureux-Dubé commented:

If members of the public had no right whatsoever to distribute leaflets or engage in other expressive activity on government-owned property (except with permission), then therea would be little if any opportunity to exercise their rights of freedom of expression. Only those with enough wealth to own land, or mass media facilities (whose ownership is largely concentrated), would be able to engage in free expression. This would subvert achievement of the Charter’s basic purpose as identified by this Court, i.e., the free exchange of ideas, open debate of public affairs, the effective working of democratic institutions and the pursuit of knowledge and truth. These eminent goals would be frustrated if for practical purposes, only the favoured few have any avenue to communicate with the public.

It’s been 19 years since the Ramsden case; I would encourage the City of Charlottetown to review this section of the Zoning and Development Bylaw with an eye to bringing it into line with the letter and spirit of the court’s ruling in that case.

(Fun fact: Chief Justice Bora Laskin, leading the court when Committee for the Commonwealth of Canada v. Canada was ruled upon, went to high school with my grandmother in Fort William, Ontario).

Although I am loathe to suggest anything that would limit freedom of expression, I think the sandwich board situation in Charlottetown is a little out of control, and there are issues of accessibility to consider separate and apart from the freedom of businesses to hawk their wares. Take the southeast corner of Queen and Richmond, for example, at the head end of Victoria Row: there are 6 sandwich board signs in the photo below, and if you were to look slightly to the right there are an additional four on the sidewalk.

I’m sure that if questioned the businesses would claim the need to direct tourist traffic their way; surely, though, we could come up with a coordinated method of achieving that goal.

I’ve not been able to parse the City of Charlottetown Zoning and Development Bylaw enough to understand what the law says on this topic; section 5.12 says:

No more than two (2) Signs, other than Facia Signs, Shall be Erected on any premises at any one time, and this includes a sandwich board Sign in the DMU Zone or on any City right-of-way.

Section 5.15.6 goes on to say:

Sandwich Signs Shall be permitted in all commercial, business Office, business Park, mixed Use, institutional, and industrial zones provided that:

- it is the only Sandwich Sign on the Lot;

- it does not obstruct pedestrian or vehicular traffic or impede visibility of pedestrians or traffic accessing the Lot;

- in the DMU zone, it does not exceed a single-faced area of 0.6 sq. m (6.4 sq. ft.), and in all other permitted zones, a single-face area Shall not exceed 1.2 sq. m (12.9 sq. ft.);

- in the DMU zone, it May be placed on the City right-of-way provided that it is located in front of the Building but not on a City sidewalk and it does not obstruct pedestrian or vehicular traffic or impede visibility of pedestrians or traffic accessing the Lot;

- if the Sign meets the size requirements of this subsection, Council May permit one (1) Sign per season on a Street corner for Buildings not located on an arterial or collector Street or require a group Sign with all Owners on one Sign; and

- the applicant Shall carry liability insurance satisfactory to the City.

I’m not sure how to relate “premises” (with a limit of 2 signs) to “zones” (with a limit of a single sign) in this language.

The City’s own Awareness Guide to Accessibility for Persons with Physical Challenges (PDF) weighs in on the issue, however, with this helpful illustration of the hazards of sandwich boards placed where people expect to be able to walk:

Posted by the King Cole tea at the Walker Drive Co-op in Charlottetown, a notice that the tea will now come in paper rather than gauze tea bags.

It would be interesting to know that the “unforseen changes in the world economy” that precipitated this are.

I am

I am