The Old Farmer’s Almanac webcam has been a longtime and surprisingly popular feature of Almanac.com, to the point where readers passing through rural Dublin, NH will often stop in the parking lot and set themselves up in front of the webcam for a special guest-starring role.

To enhance this experience, we’ve developed a system that allows visitors to text their email address to a special mobile number to start a the recording of a 10-second video clip by the webcam; this clip is then emailed to them for posterity.

Here’s an example; if you look carefully you can see the five members of our web team on the roof waving hello.

Here’s my colleague Lou coaching some visiting Finnish tourists, geocaching in the area, how to use the new system.

On the third floor of the Sagendorph Building here at Yankee Publishing, at the end of the hall near where my temporary office sits, is a room called, internally, the “crow’s nest.” Many of my meetings this week have been hosted there, and in previous years I’ve set up temporary office there; in an earlier incarnation it was the office of my friend and colleague the late John Pierce.

I can walk out of the Crow’s Nest and unto the roof of the building and appear on The Old Farmer’s Almanac webcam; here’s me doing just that (the image is tilted because the camera got tilted by construction workers):

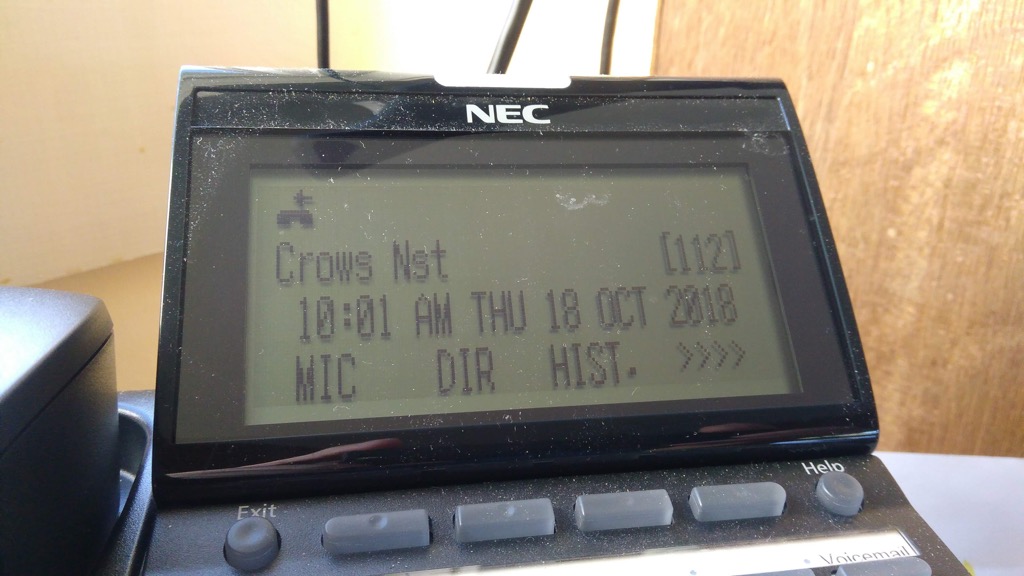

I noticed this morning that the phone in the room is labelled “Crows Nst,” which takes its unofficial name into officialdom. I love this.

Anne Gibson writes, in To whom does the burden fall?, about accessibility:

When is it the responsibility of someone with a disability to use unnamed tools to somehow make your content accessible, when your organization has not done so yourself?

Never. It is never their responsibility.

Read the entire post: it’s a well-worded call to arms.

Radiolab aired an episode featuring Kaitlin Prest’s 2017 podcast miniseries No this week. Radiolab host Jad Abumrad prefaced the episode with a caution:

Just as a warning, there are scenes in what you are about to hear that are sexually explicit, very much so, at times, and strong language… probably not the kind of thing that you want to listen to with kids anywhere nearby.

I disagree with his suggestion: listening to No is something that people of all ages need to hear, especially young people. It is a powerful examination of desire, sex, power, consent, language, and behaviour. There is open and honest talk of sex, in real language, but falling back on euphemism would work against the series, adding cloudiness to a message that at its heart is about clarity.

From the first episode:

“Come on, gimme a blow job…”

He’s gonna make me say it again.

“Ah, no… I don’t want to”

[Sigh] “Come on… gimme a blow job”

It wasn’t easier the second time. At all. He puts my hand on his dick. This was the moment that I learned that saying no wasn’t enough. Someone could wear me down, little by little. That it would start to feel like a Twilight Zone moment. Where everything was normal before, and now suddenly the walls are bending in on each other and you learn that you’re actually a ghost. You start to think you’re crazy. You feel trapped. You’re having an argument about whether you’re gonna suck a guy’s dick, and even though the air is super-tense with this argument feeling, he still wants you to suck his dick. The only way for this awful moment to end is just to do what he says. And you do it.

Maybe you tell yourself that you’re enjoying it. Maybe you tell yourself that there’s something tender about this moment. At the same time, part of you is silently screaming. It’s like a dream: you open your mouth and nothing comes out.

This is only the first of many times that I will say no and it will be ignored.

Oliver and I listened to the Radiolab episode, and then to the first episode of No, in the car together this weekend. It led us to a conversation about consent, and how you know if and how somebody wants to have sex with you, and it led Oliver to email his high school principal “Need a Conversation with Students for #MeToo. We’re Living in a Different Age of Feminism.”

He is right. And No is one of the routes to helping us understand that more deeply.

(Prest has a new podcast, for the CBC, called The Shadows, released last month)

The thing I miss most about not having proximate day to day co-workers is office hijinks. Fortunately my colleague Alan, here in New Hampshire, stepped up this morning to fill this void for my visit.

If you’re driving through Windsor, Nova Scotia on the main highway, you cannot help but notice the impressive abandoned mill building off to your side. As we had some time on our hands, on our pass by yesterday I pull off the highway to take a closer look.

The building, formerly home to Nova Scotia Textiles, has a fascinating history; its end came as the result of the Iraq war:

Oddly enough the final nail in the coffin came about as a result of the Iraq war. The mill had a contract with a company called Morning Pride, based in Dayton, Ohio, that specialized in making protective wear for firefighters. The mill had a contract to manufacture Morning Pride jackets, but a shortage of fireproof material called Nomex meant the mill’s only profitable contract was now impossible to complete.

Normex is made by DuPont, an American chemical manufacturer. Nomex, a fire-resistant, petroleum-based fibre, is a variant of Kevlar, a component of bulletproof vests. DuPont has a contract with the US Military and must fulfill these orders before it can deal with commercial orders.

In August, 2006, DuPont sent a letter advising its customers of a shortage of Nomex because of ‘continued and unexpected demand for Nomex … by the U.S. Military.”

After closing, the mill was on the cusp of redevelopment into condominiums and retail space, but the 2008 recession ground that process to a halt.

Musician Terra Spencer has a lovely song about the mill; in the song I learned that in 1897 the town of Windsor burned to the ground:

Residents were forced from their homes, but made brave efforts to save some of their belongings and homes. At the time grand pianos were one of the most valuable pieces in a home and many people pulled their pianos into the street but had to abandon them when the fire got too strong. Imagine the sight of a row of burning pianos on the streets.

Every church in Windsor was lost except the Anglican Church. Tradition tells that the students of Kings College saved the building by pouring water on the roof. Damage was estimated at two million dollars but only six hundred thousand dollars was insured. The miracle of the fire is that no lives were lost.

Regular readers may recall that my ancestors have some familiarity with towns burning to the ground.

My phone isn’t well-suited to taking three dimensional panoramas (or I’m not good at taking them); most of the time they end up as a jumble of disjointed images.

But sometimes the jumbled result is itself interesting.

(Notice Oliver’s head popping up from below).

We opted for a slow drive home today from Wolfville, starting with breakfast at the Wolfville Farmers’ Market and then heading east toward home around noon.

Rather than a straight shot across to Brookfield, or the reportedly-faster dip down to Halifax and slingshot back out the 102, we opted to hug the coast, spending most of the day on Rte. 215 along the Bay of Fundy. Autumn foliage was at the peak of its peak, and we could not have picked a better day to drive through the Nova Scotia hinterland.

The highlight of the day was coming across a camera obscura perched on a hill in Cheverie. You’d think such a wondrous attraction would deserve a sign, but there was none, and most drivers, I suspect, speed by unaware.

It’s a fascinating construction of three interlocking brick cathedrals, entered through wooden doors into a darkened room above which is a system of lenses that reflects the scene of the shore, and the Bay of Fundy beyond, onto the floor.

If you are in the Annapolis Valley, and are traveling east toward Truro, it doesn’t take much to detour up to Cheverie.

(Just up the road from Chevrerie lies Walton, which I recalled was the birthplace of my old friend Stephen Southall, something I confirmed with a phone call from the car. His late father George ministered to five United Churches in the area in the 1960s; apparently there is a plaque on the wall in the United Church in Cheverie, which is enough to inspire me to return on our next trip that way).

,

,  ,

,

Back in the early 1990s, Laurie Brown moved from MuchMusic VJ to CBC Television’s flagship The Journal as arts correspondent and, in the process, defined a new kind of cultural journalism for the country. Inside the confines of the musty corporation she reported on Canadian art, music, movies and theatre with a leather jacket, a distinctive voice, and approach that was curious, innovative, and owed little to the CBC’s usual way of reporting on the arts.

Contrast this 1981 CBC interview with Robert Bateman by Barbara McLeod with this 1996 CBC profile of the Rheostatics by Laurie Brown, for example: McLeod was a docent whose style typified the kind of arts journalism I grew up with; Brown’s approach was so much more immersed and engaged, so much more “art is of us and for us and by us.” It was a style that she took to everything she reported, and I became a regular and devoted viewer.

Moving on from television, Brown hosted The Signal on CBC Radio 2 from 2007 to 2017, years that happened to coincide with Oliver’s bedtime, and Oliver having a radio next to his bed; he fell asleep to Laurie Brown for most of his formative years.

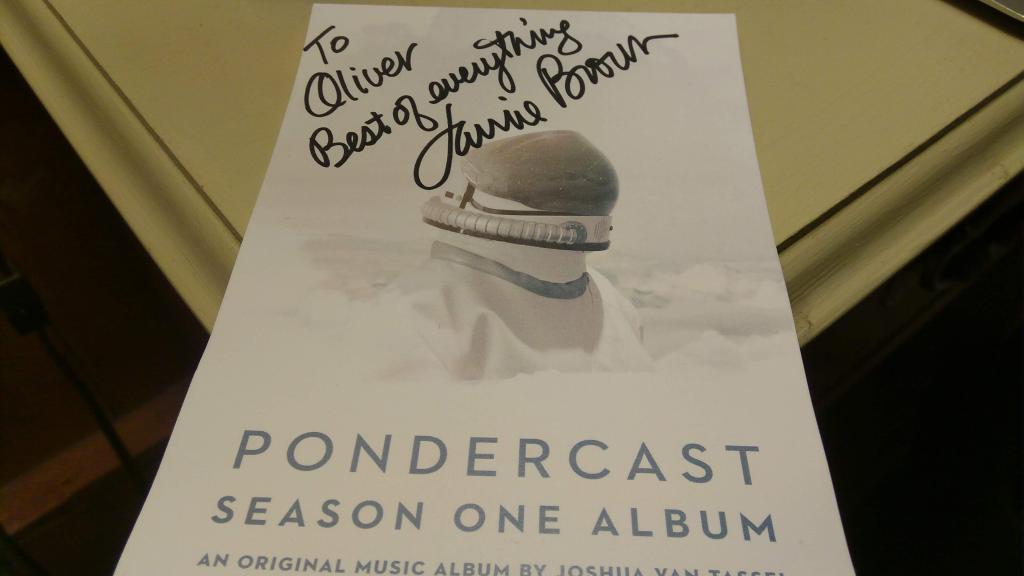

When Brown moved from the CBC to a self-produced podcast, Pondercast, Oliver, now with a podcast-playing Google Home in his bedroom, followed her there, and has been a devoted and regular listener.

And so when an Atlantic Canadian tour of live podcast tapings was announced for this fall, Oliver let it be known that he needed to attend one; as Oliver has seldom expressed such a definitive need for any activity, I jumped at the chance to build a visit to the Wolfville taping into his “birthday season.”

Which is how we found ourselves in the famed Al Whittle Theatre tonight listening to Laurie Brown’s words and Joshua Van Tassel’s sounds.

It was a delightful show, one that brought to mind Oscar Wilde’s similar tour of the Maritimes in 1882, a tour described like this:

In an era that saw rapid technological changes, social upheaval, and an ever-widening gap between rich and poor, he delivered a powerful anti-materialistic message about art and the need for beauty.

The episode we witnessed tonight was very much in that spirit: over a bed of Van Tassel’s sonic creations, Brown delivered an extended rumination on the sea, the horizon, on memory and repetition and learning, on Darwin and evolution, on whales, and on what it is that we call home.

When I was Oliver’s age, Laurie Brown was the apotheosis of cool in Canada, turning a format on its ear and injecting new life into it; 30 years and several reinventions on, she’s managed to continue to be that still.

Do attend a taping if you’re near, you will not regret it.

I am

I am