There was a story told in the composing room of the Peterborough Examiner that, during the days the type was cast from hot metal, a typecasting machine got stuck–perhaps while its operator was distracted, perhaps distracted by the drink–and started spewing freshly-cast type out the window onto Water Street. I suspect that the story was apocryphal, but that newspapering was well-lubricated by alcohol, and typecasting machines among the most complex ever created by 19th century humans, led some credence to it.

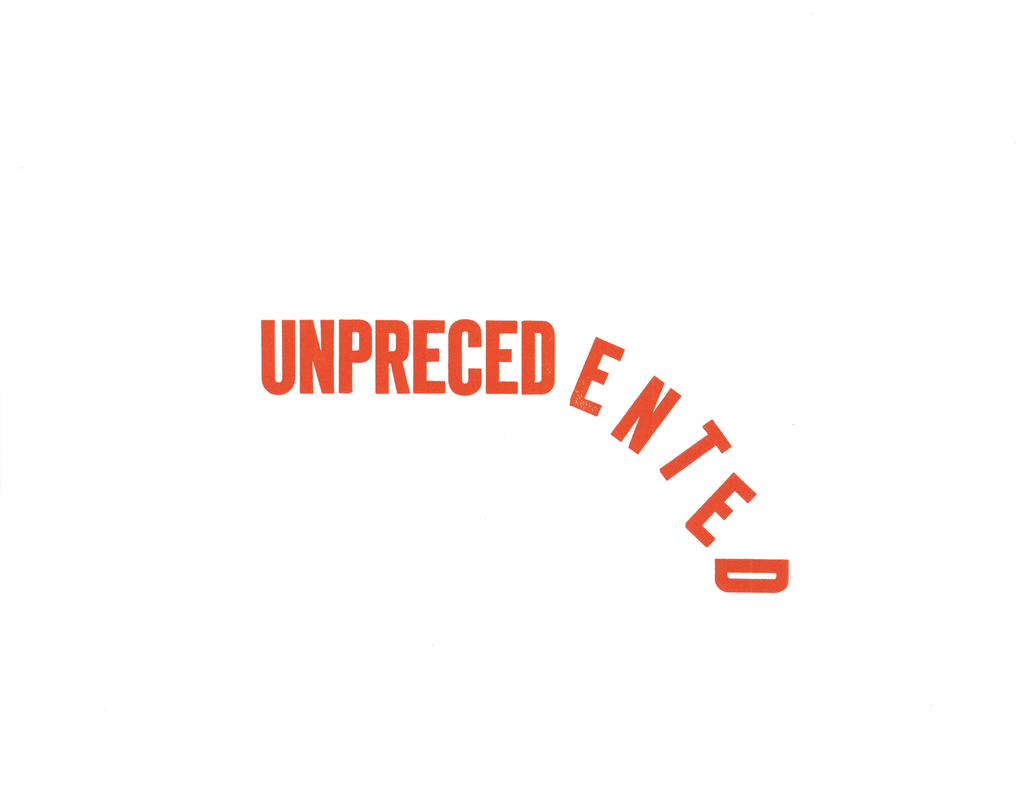

A few weeks ago, after hearing the word “unprecedented” used dozens of times in a single day on the news and in advertising, I started to imagine a letterpress print that would capture the word and its role in the COVID zeitgeist, I thought back to that story, and imagined type waterfalling out of the composing room and onto the sidewalk below.

Setting type in straight lines is, relatively speaking, easy. Setting type meant to be falling out a window, hmmm. Outfitted with confidence from this summer’s daredevil printing workshop, I set out to find a way to translate what was in my mind’s eye into the chase.

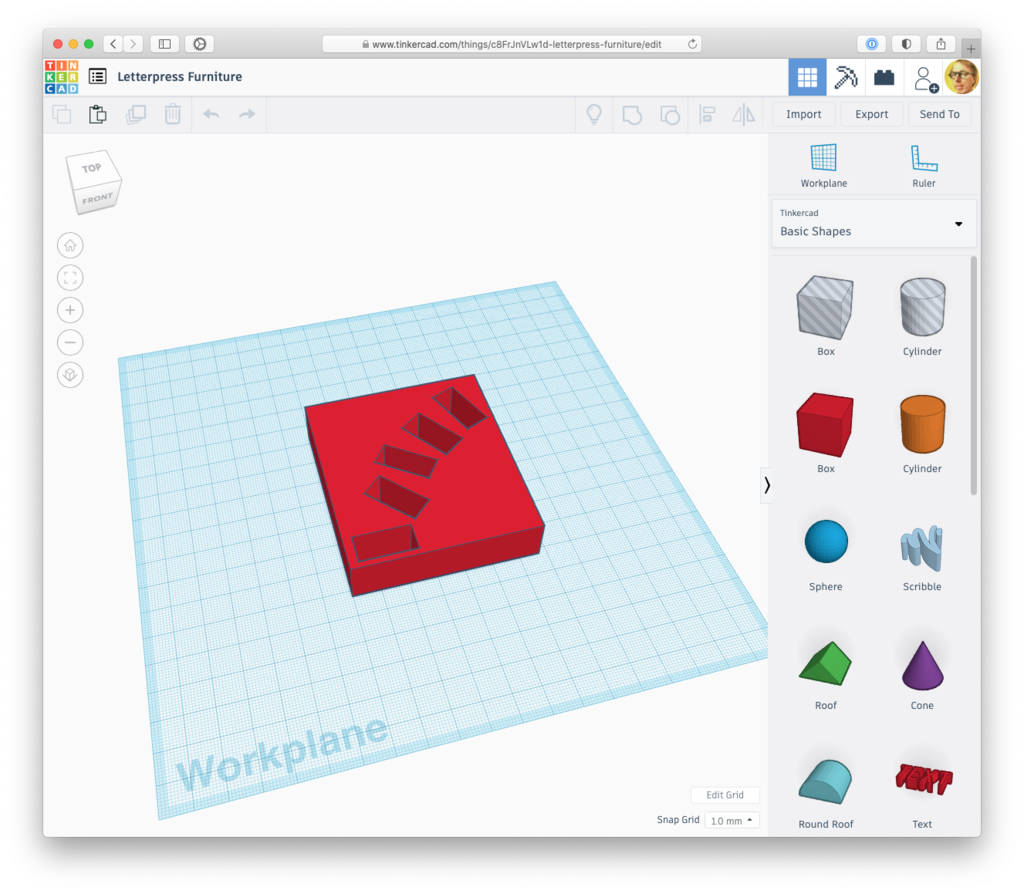

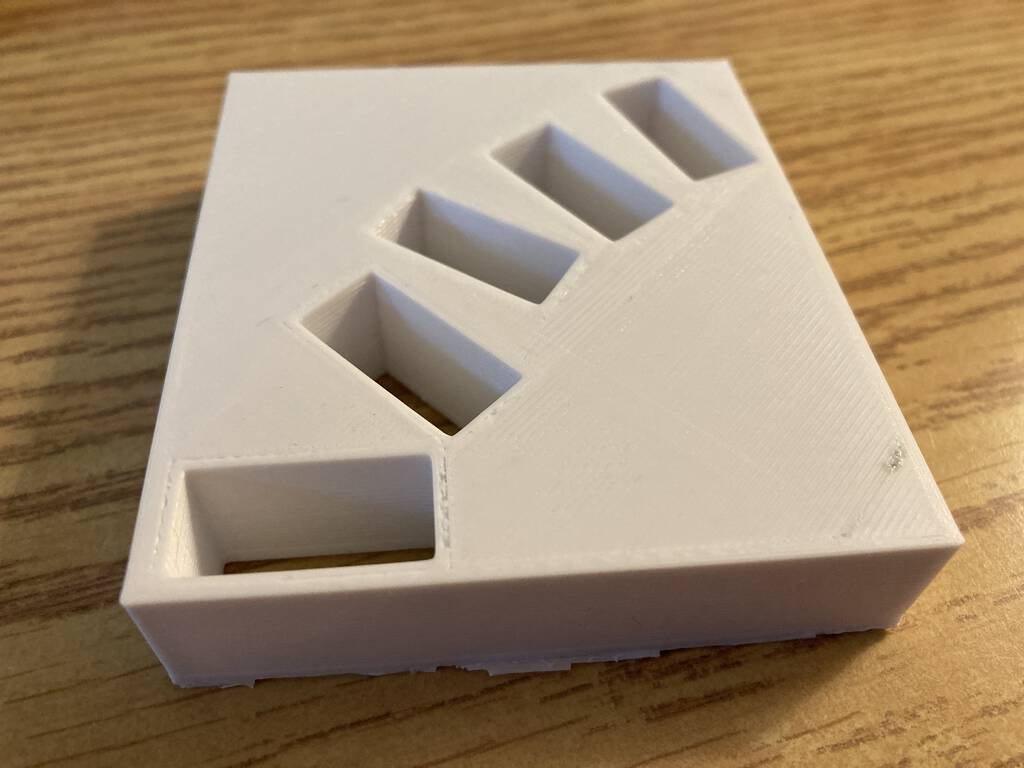

What resulted, as described here, was a 3D printed piece of letterpress furniture to hold the cascading letters; it took some jimmying, but I got the type slotted into the furniture and locked into the chase with the typically-set type, and the result, once inked, looked like this:

Getting to the point where the printing of UNPRECED and ENTED matched took some makeready (I had to increase the packing under UNPRECED); the resulting print, which matches what was in my imagination to a very satisfying degree, looks like this:

I find myself getting a little destabilized every time I look at it. Which, of course, is kind of the point.

Ten years ago in Copenhagen I heard my friend Elmine’s brother Siert Wijnia, with Erik de Bruijn, talk about the RepRap project:

Democratizing fabrication - The beginning of this talk will be about the RepRap, a Replicating Rapid Prototyper. In short, it is a fabricator, or 3D printer, that makes things that YOU want. Besides being able to make products as you like them best, it can make parts to assemble another RepRap machine. Hence, it has a viral distribution model.

The next year, Siert and Erik, along with Martijn Elserman, went on to found Ultimaker, a company that, in the intervening years, has grown into a major manufacturer of 3D printers.

Cura is the software that drives Ultimaker printers and, because Ultimaker is a company that has openess baked into its DNA, Cura is a remarkably open piece of software, capable of driving a variety of 3D printers that aren’t made by Ultimaker, including my own Monoprice Select Mini.

Until today, my use of Cura had been limited to using its ability to render 3D printed objects I create as STL files into the G-code files that my printer needs to print them.

For example, here’s an object, a piece of custom letterpress furniture I designed, in Tinkercad:

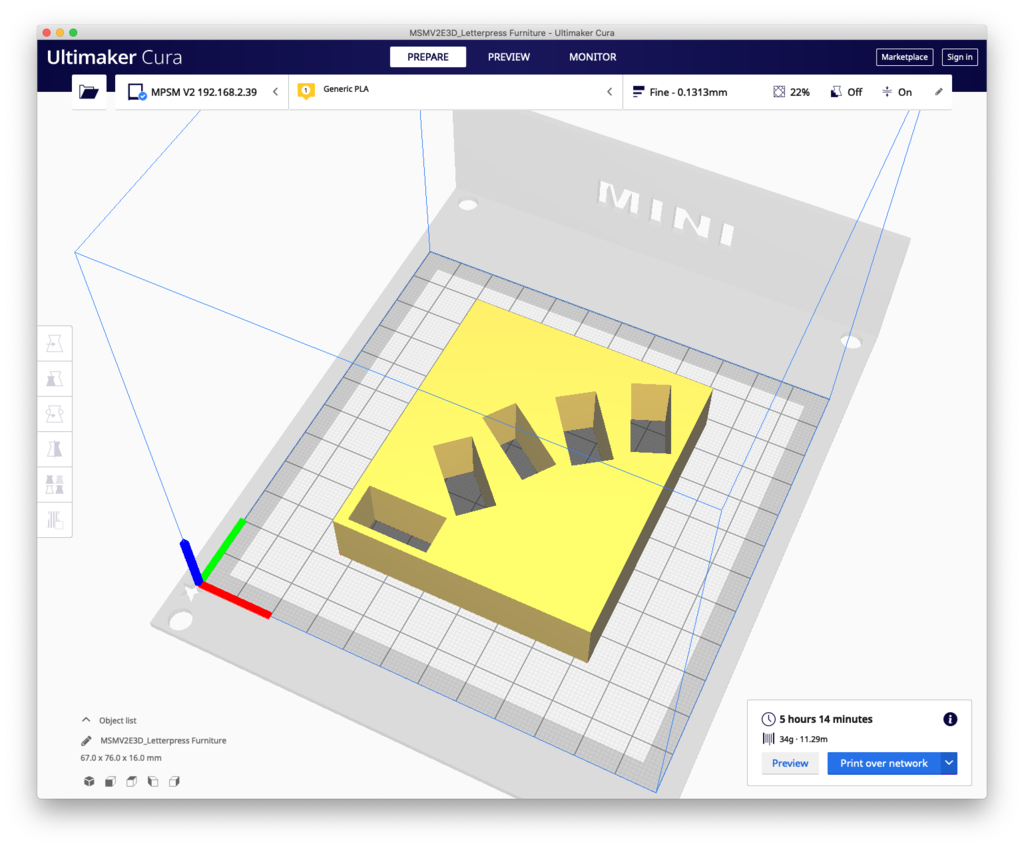

I exported a STL file from Tinkercad and loaded it into Cura, which tells, me, among other things, that it will take 5 hours and 14 minutes to print:

At this point it has been my usual practice to save the G-code needed to render the object to an SD card, pop the SD card out of my Mac and insert it into the 3D printer, and use the printer’s controls to select the file and print it.

Today, though, I discovered a plug-in for Cura that allows it to print to the Monoprice Select Mini directly, over wifi. And it worked, out of the box. So my new practice is to simply click “Print over network” in Cura and wait for the printer to start.

Because I wasn’t eager to spend 5 hours and 14 minutes waiting for the printer to finish, but also not eager to let the printer, and its 210ºC head, alone to malfunction and catch fire, I wanted a way to monitor the printer from afar.

Fortunately, under the aegis of another side-project, I’ve been experimenting with video streaming from a Raspberry Pi Zero; following the helpful instructions here, I set up the Pi to stream video to YouTube, pointed it at the 3D printer, and, presto, I had a remote monitoring solution.

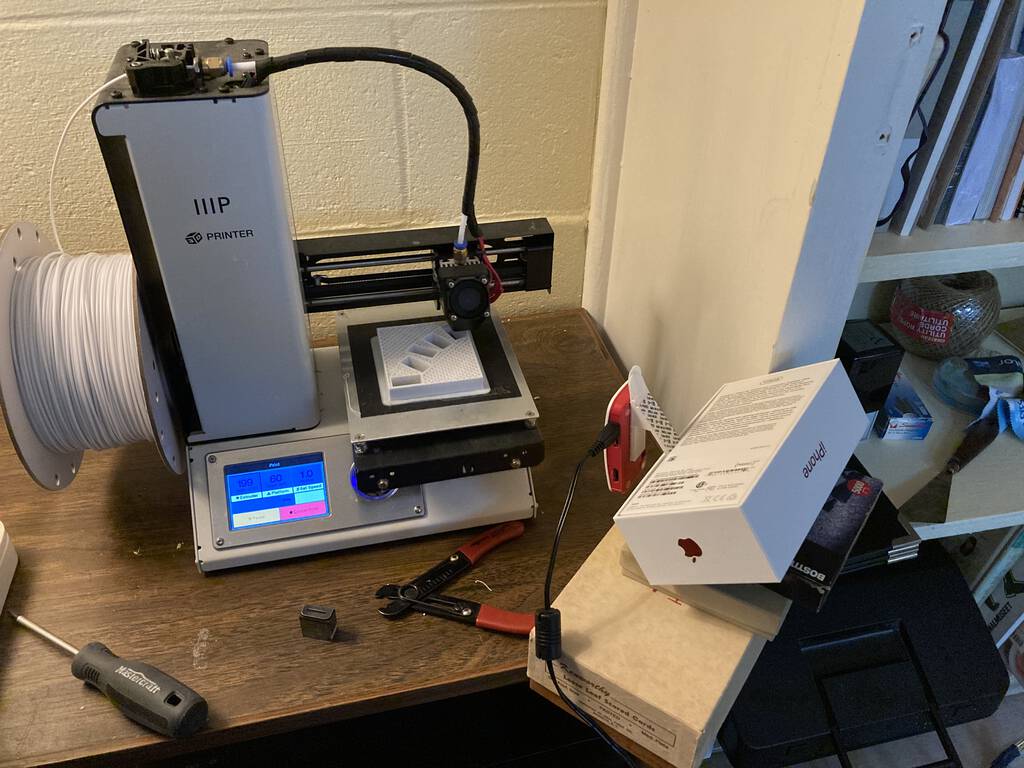

From the office side it looks like this:

That’s the 3D printer on the left, and the Raspberry Pi Zero on the right, stuck into an iPhone box (it’s really really tiny, has the camera built-in, and only needs to be plugged into power to operate). With the YouTube stream set up, I was able to watch the printer from my phone:

Even more helpfully, though, for something that I wanted to keep peripheral attention on for several hours, I was able to stream YouTube to my Chromecast, plugged into my screen projector, resulting in a hard-to-miss 3D printer monitor on my living room wall:

I kept an eye on the printer over supper, and afterwards, and came back to the office once things were getting close to complete.

In the end, it took 5 hours and 41 minutes to print, and this was the result:

And here’s a sneak peak at what this was all in service of:

The first on-street EV charger in Charlottetown sprouted this week in front of Maritime Electric‘s headquarters.

Watching Sylvan Esso at work makes me want to chuck it all and become part of an electropop duo. Or at least to cultivate a better fashion sense and a more delicate quotidian choreography.

In the summer of 2017, Catherine started a round of Docetaxel, a chemotherapy drug, with the goal of reducing the size of the tumours in her back, shoulder and skull. Because Docetaxel is known to cause an allergic reaction. she was given the steroid Dexamethasone beforehand to counteract this.

The effect of the Dexamethasone was dramatic; as I related in my newsletter to friends and family:

Catherine tolerated her third treatment of the chemotherapy drug Docetaxel well on Monday, and her plan to more gradually come down off the high of the Dexamethasone (steroids she takes to help control allergic reactions) seems to be bearing fruit. She’s still reaching a point where she crashes into fatigue, but the crash is gentler (and is happening today).

While she’s in thrall of the Dexamethasone the effect is not unlike what one might imagine it must be like to take large amounts of cocaine: everything’s sped up, she has lots of superhuman energy, and she talks faster than you’ve ever heard her talk.

Fortunately she’s learned that the superhuman energy doesn’t correlate to superhuman abilities, so has taken to locking herself in the care of our friend Carol to prevent herself from taking on large renovation projects by mistake.

It’s Dexamethasone that President Trump has been taking as part of his COVID-19 treatment. Having a President who thinks he’s superhuman (when he already thought he was superhuman) seems like a recipe for (even more) disaster.

It’s taken me almost 9 months and one pandemic, but I’ve got Catherine’s fabric, yarn, fleece and various and sundry tools boxed and ready for pickup by volunteers from the G’ma Circle of Charlottetown. They’ll be part of the Fabric and Yarn Sale, in support of the Stephen Lewis Foundation’s Grandmothers to Grandmothers Campaign (the sale will, touch wood, happen sometime in 2021, pandemic-willing).

Getting to this point has been bracing: Catherine’s collection was vast, collected over decades, and the clearest representation of her and her sensibilities; wading through that has not been without its emotional challenges, and I got here only be rationing the work into small chunks, a little every day.

Grandmothers to Grandmothers is a project that Catherine would have loved, and knowing that her materials and tools will be in the hands of people who will make them into things takes away some of the sting of imagining all the things that went unrealized by her hand.

This is not to suggest that her studio is empty yet: I’m hopeful that Habitat for Humanity will come and pick up the furniture and shelving, which will leave me only with the task of finding an appropriate way of documenting and preserving the archive of work she left in her wake.

There are problems that are gnarly and hard and take years or millions or both to solve.

Then there are problems that, relatively speaking, are easy to solve.

Like getting books into the hands of Prince Edward Island children, something the PEI Literacy Alliance has undertaken to do with its simply-named Free Books for Kids project:

Each month, enrolled children receive a high quality, age-appropriate book in the mail, free of charge. Children receive books from birth up to their fifth birthday.

This project, launched last week, was almost instantly fully subscribed, the CBC reported:

“We thought we would spend a year encouraging people to register and promoting it and all that sort of stuff, so we were very shocked,” said P.E.I. Literacy Alliance executive director Jinny Greaves.

“Within 24 hours we had exceeded our goal for year one, and we’re really going to try … within the next weeks or months or a little bit more to be able to serve another additional 1,000 children or maybe even more.”

Last week my mother told me that a Lorraine Eastwood, librarian at the Waterdown Public Library, a short walk from my high school and a refuge therefrom, died this summer. In her memory, upon reading that a project to give free books to kids was too popular, I made a $100 donation to the PEI Literacy Alliance.

You’re probably saying to yourself right about now, “can I do that too?!”

And you can: just go here to donate. It takes about 58 seconds.

I was telling my friend Martin about this on the weekend, and he said “that could be a contribution to making PEI Canada’s first Heaven on Earth province.”

Martin has, with uncommon patience and candour, been wearing down my natural cynical resistance to his Project Heaven on Earth, which he introduces with:

There is a desire, a longing, in each of us for a world that works.

A statement that’s hard to argue with.

And so this is, indeed, a small contribution to that.

With an important coda: once you make your generous donation to providing free books for kids, please ask someone else to do the same thing.

This is easy to do, in my experience, as getting behind the idea providing free books for kids is roughly equivalent to getting behind the idea of providing free oxygen to kids.

The word will spread.

The program will re-open its floodgates.

All kids who request them will receive books in the mail every month.

And there will, indeed, be a world that, at least a little bit, works.

I have, slowly but surely, been cleaning up the room on our first floor variously known, over the years, as “the office,” “the situation room,” and ”the library.”

Catherine designed the mantlepiece and the shelving, which included a liquor cabinet complete with its own light. Last fall, around this time, when she could no longer navigate the stairs to the second floor, she moved her bedroom here, and so it was, for a time, “Catherine’s room.”

Some weeks ago Oliver and I somehow managed to wrangle the couch, from Catherine’s studio, across the street and into the house; it fits the room well, and arrived just in time to serve as a makeshift bed for our friend Yvonne, who visited this weekend from Halifax. Her visit was all I needed to make the last push toward cleaning the room up: I loaded up a Kia Soul’s worth of various and sundry and dropped it at the thrift shop, dusted and vacuumed, and generally got things ship-shape.

Which allowed me to open the curtains for the first time in a long time.

And to discover that the room gets wonderful sun in the afternoon.

On this night, around this time, 29 years ago, this woman asked if she could kiss me. The rest is history.

I am

I am