Josh MacFadyen published an article in NiCHE earlier this month, The Stubborn Commuter, that dwells in the heart of a whole big bunch of things I’m passionate about: cycling, active transportation, land use, urban planning, maps, GIS.

This is what keeps me stubbornly commuting to work. Between my PhD in early 2010 and today, I’ve been fortunate to find work at UPEI, Western, Saskatchewan, Arizona State, and now UPEI, again. I have bought exactly zero semesters of parking passes from any of those universities. My wife and I have fought the urge to get a second vehicle, or to “put another one on the road” as they say in PEI. It’s a challenge with a busy and relatively large family. It means we run a house with exactly 0.16 cars per person. Our bike fleet fluctuates, but it is usually closer to 1.5 bikes per family member.

It was the last good autumn day before a big stretch of rain and strong winds, and so a good day to clean up the back garden and pick the remaining apples on the trees to make the final batch of applesauce for the season.

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

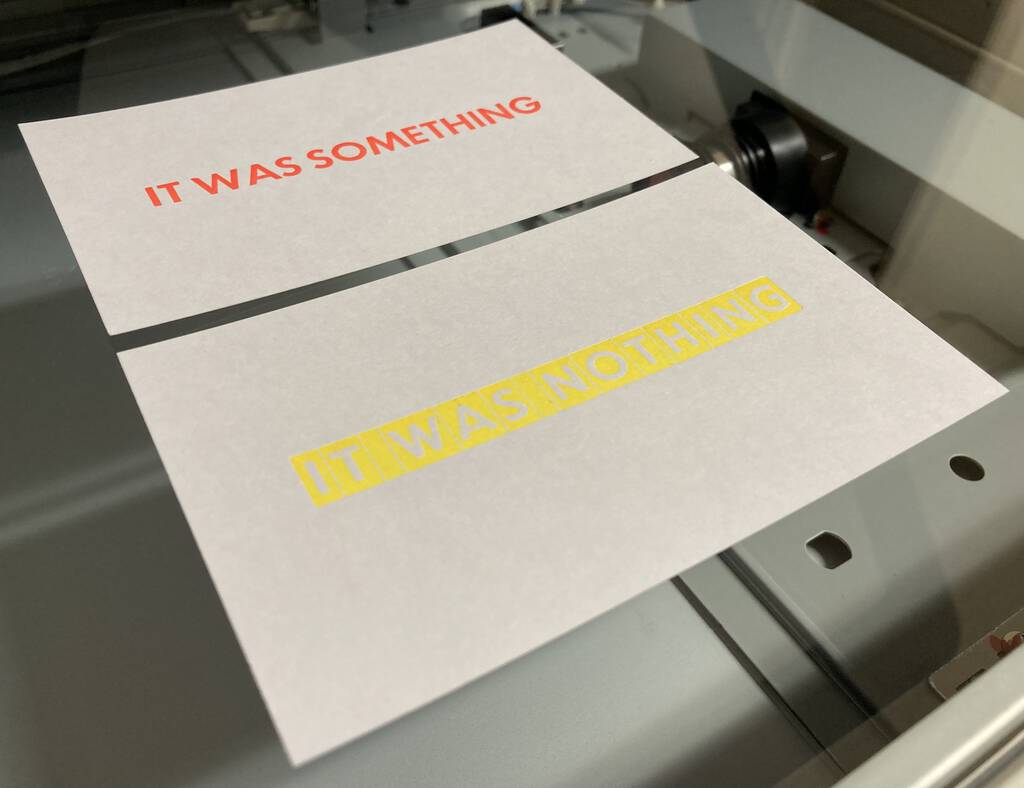

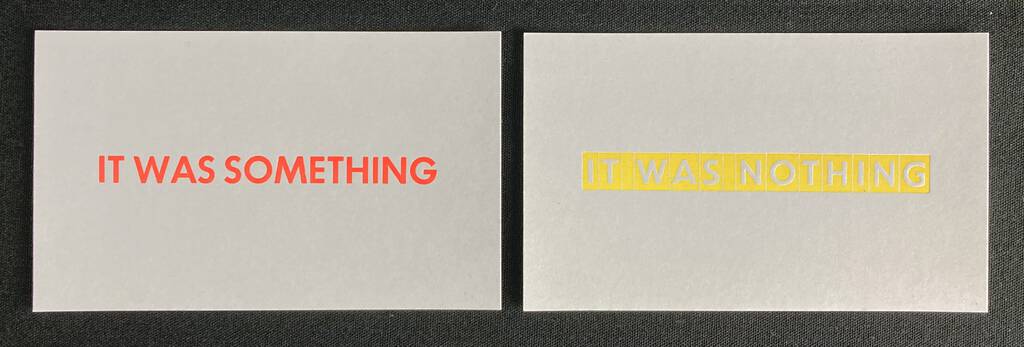

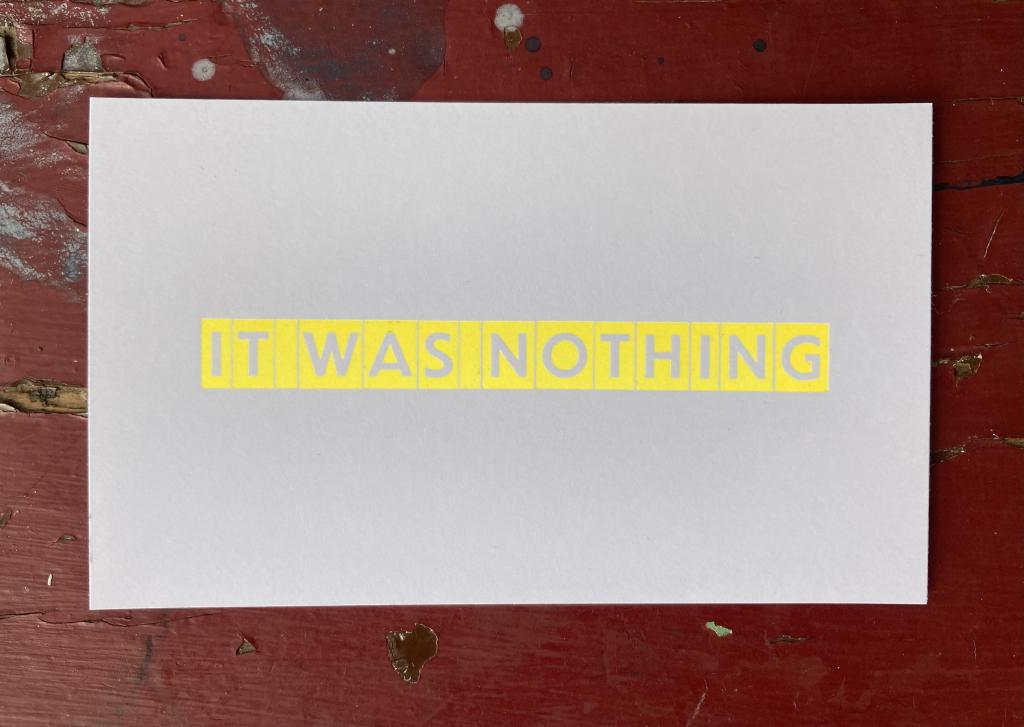

I experimented with printing with florescent inks today and discovered that it’s impossible to do justice to the result in a photograph, so you’ll have to trust me that there’s more to these than meets the digital eye. The “It Was Nothing,” in particular, printed in florescent yellow in reversed type, makes my iPhone’s brain explode when trying to focus.

Regardless, the psychotherapeutic result was achieved, as, for that, it’s only my hands and eyes that were important, and I’m standing right here in the analog world.

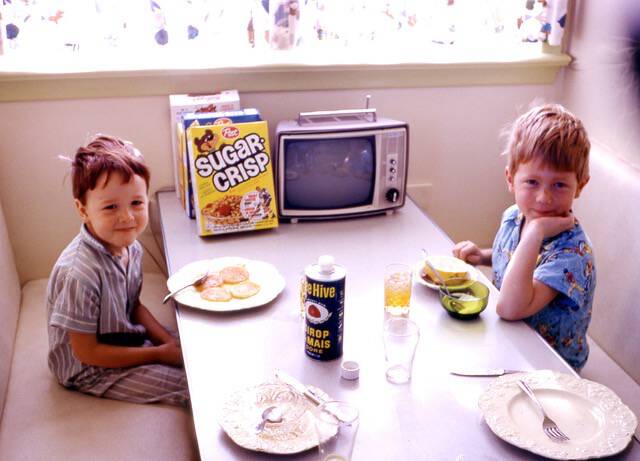

It’s my brother Mike’s birthday today. Here are the two of us, slightly younger (Mike on the left, me on the right), eating breakfast at 1471 Augustine Drive in Burlington, where we lived from 1968 to 1972. Clearly sugar was a bigger part of our diet then. And television, at the breakfast table!

The great and glorious positive development of autumn 2021 is that my mother, Mike, and Mike’s partner Karen have relocated from Ontario to Charlottetown and live a short walk up the street. None of us have lived in the same city since the mid-1980s, and it’s been a delight for both Olivia and I to have them handy-by.

Mike and I are going out to birthday lunch today, which might seem like the most regular and normal thing in the world but, in our case, is a new and special superpower.

Shortly after Catherine was diagnosed with cancer she was matched with an anonymous volunteer peer, someone who knew more of the drill, for emotional and logistical support.

The lasting effect of their very first phone call was the recommendation that, to prepare for times when Catherine would be immune-compromised, we switch to using individual hand towels in the washroom. In a sea of “there’s nothing to be done” this was a thing to do.

A so a trip to Sears was made, a case of hand towels purchased, and the upstairs and downstairs washrooms stocked.

The weekly gathering, laundering, and folding of these towels continues to this day, outliving Catherine and the reasons that begat it.

But I continue, both because at this point the notion of sharing a single towel for drying the household hands seems a violation of good public health guidance, and more so because it’s a comforting ritual, folding warm towels while Olivia gets ready for bed on Sunday nights.

Kudos to Green MLA Lynne Lund for highlighting the cost and complexity of officially changing name and gender designation on PEI.

When government removes these fees, streamlines the paperwork, and removes the requirement for a doctor sign-off, it will be a small but significant step toward embracing trans and non-binary Islanders.

There’s no better time to get this done than right now, during Transgender Awareness Week.

I’m happy to report that—touch wood—the unseasonably late November fruit fly season appears to have come to an end.

I wish I could claim credit for this by way of my multi-pronged—bleach-in-drains, apple cider vinegar and beer traps, vigorous vacuuming—mitigation strategy, but I suspect it was simply the turn in the weather that did it.

Some books are worth acquiring simply for the title; It’s OK That You’re Not OK, by Megan Devine, is one: being released from the pressure to be OK is a great gift.

Devine’s central thesis regarding grief boils down to “you’re fucked up, get used to it” or, more gently, “grief isn’t something you recover from, get over, or move through, it’s something you learn to carry.” Despite how depressing that seems on first reading, it’s liberating metaphysics for someone in my position.

Our culture sees grief as a kind of malady: a terrifying, messy emotion that needs to be cleaned up and put behind us as soon as possible. As a result, we have outdated beliefs around how long grief should last and what it should look like. We see it as something to overcome, something to fix, rather than something to tend or support. Even our clinicians are trained to see grief as a disorder rather than a natural response to deep loss. When the professionals don’t know how to handle grief, the rest of us can hardly be expected to respond with skill and grace.

Reading the book unlocked a realization of just how much I’ve been trying to shape an “I’m OK” narrative, with deep hope that it would be true (or might become true on repeated telling).

On a personal level, repressing pain and hardship creates an internally unsustainable condition, wherein we must medicate and manage our true sadness and grief in order to maintain an outer semblance of “happiness.” We don’t lie to ourselves well. Unaddressed and unacknowledged pain doesn’t go away. It attempts to be heard in any way it can, often manifesting in substance addiction, anxiety and depression, and social isolation. Unheard pain helps perpetuate cycles of abuse by trapping victims in a pattern of living out or displacing their trauma onto others.

Writing I am not OK makes me feel like such a failure.

But it’s also such a relief.

I am

I am