Today was the start of Grade Four for [[Oliver]]. The first day of Grade One seems like an eternity ago:

Several good friends from previous grades are in Mr. Doucette’s class with Oliver this year; a couple aren’t. Although he’s still in Prince Street School, the jump from Grade Three to Grade Four means moving upstairs, taking French for the first time, a new time for recess, and who knows what else. It’s an exciting time, and Oliver was in fine form, primed and ready for action.

From the Maysville, Kentucky newspaper The Evening Bulletin, October 3, 1896, I’ve come across “PRINCE EDWARD LAND: The Simple Capital of a British Province and Its American Visitors”, which reads as follows:

Charlottetown, PEI, Sept. 10. – This little town is cut off from the world in an aggravating way. The coast of Nova Scotia is in plain view along most of the southern coast of Prince Edward Island, but the transfer by boat from Pictou takes three hours, so it is almost as long a journey from Halifax to Charlottetown as from Halifax to Sidney, twice as far away. This fact and the utter absence of any picturesque feature on the island would make Charlottetown a place unknown to any but commercial travelers or insurance agents if it were not that a Boston steamship line has made this place its terminus. Once a week the big ship from Boston, which has stopped at Halifax and Hawkesbury en route, comes to her wharf at Charlottetown and discharges a shipload of passengers. They are chiefly from Boston and interior Massachusetts. Some of them are from New York and Philadelphia and even cities of the west. All have come for the sail. They don’t care a fig for Charlottetown. The chance to spend six days on the ocean with opportunities at several intervals to “get off and walk” for a change draws from 50 to 200 people from Boston every week. Many would much rather stick to their pleasant berths aboard ship when they reach their destination, but most of the passengers go ashore for the night. So Thursday nights are gala occasions in Charlottetown, and the greater part of the population gathers at the wharf. The people arranged in tiers on a bank that looks down on the landing, and they fight for position near the entrance to the shed through which the travelers must pass. What satisfaction this crowd gathers from gaping uncomfortably in the semidarkness at the string of commonplace men and women, satchel laden, filing out of the shed is comprehensible, I think, to none but a Charlottetown mind. That there must be some satisfaction is plain from the fact that the crowd is as great at the end of the season as it is at the beginning.

They have primitive ways of running a hotel in this country. When you register, the clerk assigns you to a room and waves you toward the stairway. You climb three flights of stairs and find your way along the hall to the room. The door stands hospitably open. The key is in the lock. This at least is an improvement on Halifax, where the keys, having no tags attached, are carried off by the guests, leaving the next occupant of a room no protection but a chair braced against his door.

Charlottetown surrounds Queen’s Square, an oblong strip of parking very prettily laid out. Facing the park are the provincial parliament buildings of graystone. Adjoining are the post office and the city hall. Beyond the post office is a long market, whose odors are an offense against the pretty place. Outside this square Charlottetown suggests nothing so much as a small county seat in Illinois. All the merchants of the town are gathered in two or three streets near the square, and their establishments are very like American country stores. All the sights of Charlottetown can be exhausted in half an hour, and the traveler welcomes the time when a blast from the steamer’s hoarse whistle warns him that it it time to start on the homeward trip. – Grant Hamilton.

After using my Adana Eight Five largely unchanged from the way it arrived on my doorstep, I decided it was time to see about making some adjustments to the press bed to get more even printing. I followed the instructions in the owner’s manual:

Your machine was fully tested before despatch, but should adjustments be needed to even the pressure, or to adjust for a lighter or heavier forme, this is done by the four impression screws. After making a number of such adjustments it may be necessary to square up the type bed. Slacken off all impression screws and renew the padding. A test forme should be set by placing four large pieces of type (24 point or over) one at each comer of the chase. Ink up and print as normal, but hold the handle down on its stops. With the other hand tighten the impression screws until they are touching the bed to the same degree, and the four corners print with the same density. This is not dilïicult to do if you work slowly. Tighten each impression screw a small amount at a time and then tighten the next in sequence.

The effect of doing this adjustment was dramatic: when I started the top two 24 point boxes I used were printed about 50% and the bottom two didn’t print at all. After 15 minutes of adjustement I had nice, clear impressions from all four.

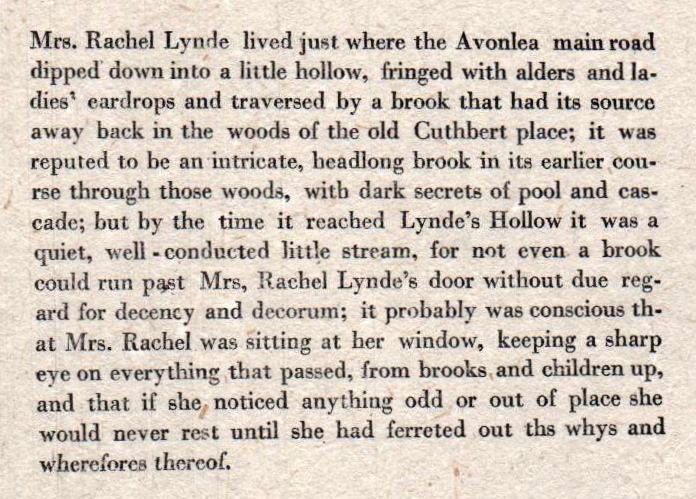

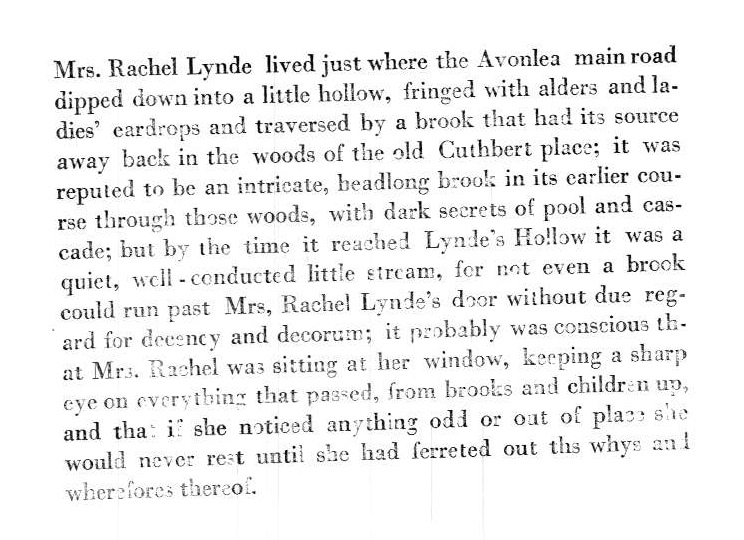

With the press adjusted I decided to try printing the first sentence of Anne of Green Gables to see what the effect would be on a real job. Again, the improvement was rather dramatic: prints I made yesterday were faded and incompletely printed in many places; here’s what the print I made today (on HazelTree straw paper) looked like:

It still needs some work, but at least the work is the same across the breadth of the type. Of course being clear enough to read points out some glaring issues with the setting of the type itself: hyphenating that for example, or adding spaces around the hyphens in well-conducted. Oh, and there’s that ths in the second-last line that needs its ‘s’ swapped out for an ‘e’. I’ll have to work on those.

But it’s certainly getting better; here’s a print on the same paper that I took before the entire sentence was set and before I adjusted the press:

I’m getting close enough to “real printed text” that I can see the end.

The opening section of The Young Job Printer contain a very useful glossary. In particular, three terms have served me well today:

Planer.—A smooth block of hardwood used for leveling the surface of type-forms after they have been imposed. The planer is laid on the face of the type and then tapped gently with the mallet.

Proof.—An impression taken from a form before it is sent to the press. The proof is read and compared carefully with the copy, the errors marked on it, and then given to the compositor to correct. After the matter or the form has been corrected, a second proof is taken. This is again read by copy, and should there be any errors found, another proof or revise is taken. The last proof, on which there are no errors discovered, is called a revise.

Proof Planer.—A planer covered with felt cloth, used for taking what is called a stone-proof. The form as it lies on the stone is inked and a piece of dampened paper laid carefully on top. Then the proof-planer is laid down carefully and tapped with the mallet, until a good impression is secured.

From these three definitions I was able to concoct a method for pulling a “proof” of the first sentence of Anne of Green Gables without messing about with the press (which saves a lot of cleanup).

First I rolled out some oil-based ink onto a piece of plexiglass with Speedball roller. I then rolled the ink over the type. Next I spritzed a fine mist of water out of an old Windex bottle onto a flat surface; I then laid a sheet of white bond paper into the mist so that it became a “dampened paper.” I took this sheet of paper and placed it, less-wet-side-down, into the inked type. Finally, I placed a piece of think felty fabric over the paper, and over that a piece of plywood – together they formed a makeshift “proof planer” – and rolled a clean roller over the plywood.

The result was this:

It’s not perfect. But then again it’s not supposed to be: it’s only a proof. And it’s just about clear enough for me to actually “proof” the copy before making any corrections and then moving to print on the press.

Our colleague Heidi at The Old Farmer’s Almanac has put together a great little video about the hole that’s in top-left corner of every copy of the book:

More useful insights from the The Young Job Printer from 1889 that foreshadow issues we face every day with web design.

The importance of standards:

Simple is better:

Regular readers will recall that I briefly flirted with a Kindle before selling it due to general discomfort with the physical force required to turn the pages.

Since that time I’ve continued to keep an eye on the “e-book reader” market: I’ve tried out iBooks on the iPad, handled the Kobo and the Sony Readers, and sought the advice of friends who are more seasons e-readers than I. And nothing I learned convinced me that there’s an ebook solution that works for me ergonomically.

And then I discovered Google Books. Or, rather, rediscovered.

I’d known it was there all along, and I’d followed the various legal twists and turns of (insert name of aggrieved party) vs. Google (well-aided by a chance dinner conversation with David Weinberger who nicely summed it all up for me).

But Google Books had never really caught my interest, mostly because its fully-readable books are mostly those out-of-copyright. And gripping though some of those books may be, man cannot get by on The House of the Seven Gables alone.

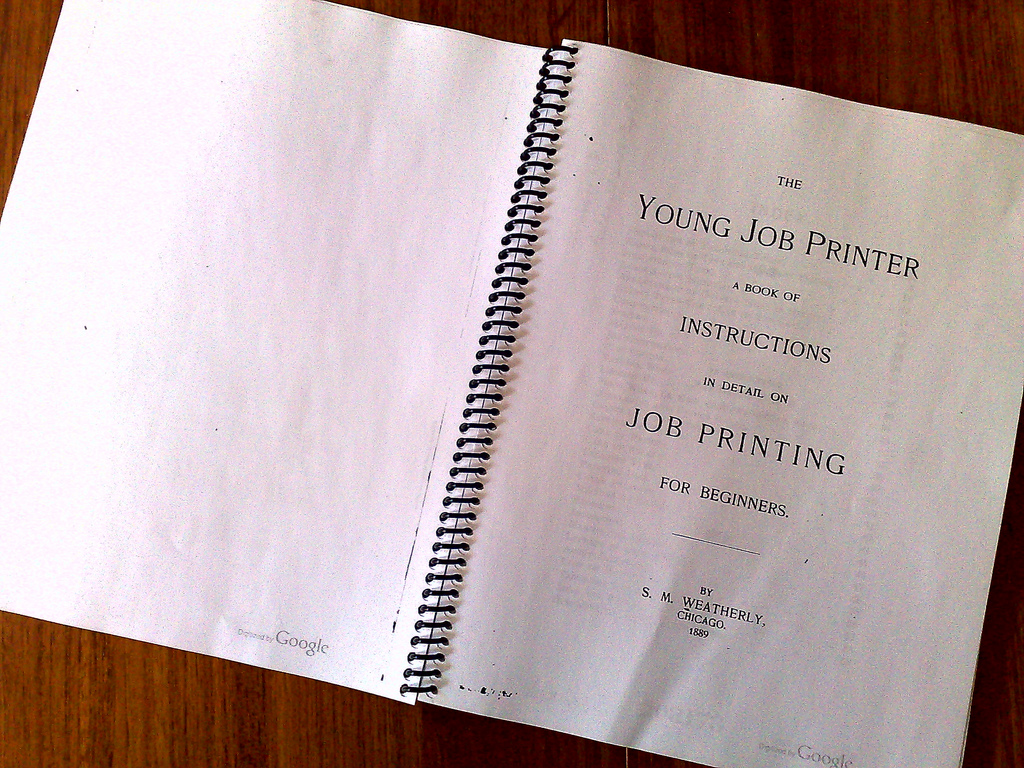

And then I suddenly became deeply interested in letterpress printing. And the great thing about letterpress printing is that it’s a technology that has its modern technical heart in the 1800s. And so most of the really good books about letterpress printing were written in the 1800s. And a lot of those books have been scanned by Google.

Google handily makes PDF downloads available of their full versions of these books, and so all I needed to profit from the wisdom contained within them was a workable e-reading solution that worked with PDFs.

But, like I said, none of the e-readers I’ve seen are “workable” for me, and I’m just not the kind of guy who can take any pleasure in reading while seated in front of a computer screen.

So I decided to opt, instead, for Shawn.

Shawn Mackenzie runs the local Kwik Kopy, conveniently located a block from my office. And Shawn has been following along with my letterpress adventures since I looked at some gear he was selling back in April (he also happens to own a very sweet Golding Jobber press – you can see it in the front window of the shop – that’s in mint condition, albeit not in use at the moment).

So here’s my e-reading solution:

- Find book in Google Books.

- Download PDF.

- Email PDF to Shawn.

- Pick up printed and bound copy of book at Kwik Kopy a few hours later.

It’s not all that expensive – 10 cents a double-sided page, including cover and coil binding. So this book, for example, cost me $7.36 to have printed.

The end result is way, way better than any e-reader I’ve found:

- the type is large and easy to read;

- I can write notes anywhere in pen or pencil;

- no need to worry about batteries or light conditions or about getting crumbs on the book – I can throw the book in my bicycle basket and carry it to lunch (which is why that first page is a little crinkled);

- I can easy share the book – I just hand it to someone else, or get Shawn to run off another copy;

- And the ergonomics of page turning: well, it just works for me.

I wrote about a similar project I undertook last year which involved getting a modern “open sourced” book printed up at Staples; using Shawn to print my books means I don’t have to get out to Staples, and allows me, in a small way, to support a locally-owned business here in the neighbourhood.

The really great thing about using Google Books as the “library” from which to draw is that while I have my printed book for actual reading, I can take advantage of Google Books’ excellent searching, clipping and organizing tools along with the printed book. The best of all worlds.

We think hacking was invented in the 1960s. And maybe that’s when the word came into common use to mean “inventive workaround.”

But inventive workarounds predate hacking; take this example from The printers’ handbook of trade recipes, hints, & suggestions relating to letterpress and lithographic printing (surely a precursor to the O’Reilly books with the same spirit) on the subject of how to make accented letters from scratch:

Soldering on the top part of a colon with a small blowpipe: blows my mind. The closest I’ve ever come is using cabbages as a stand-in for brussels sprouts.

Apologies for the raft of letterpress book snippets; I’m plumbing the depths of Google Books and finding an amazing – at least to me – collection of letterpress books from the 1800s.

In Harper’s, volume 75 from June 1887 there’s an article by R.R. Bowker on how books are printed, part of the magazine’s “Great American Industries” series. My favourite paragraph concerns attempts to replace human printers with “steam men”:

You may recognize the name R.R. Bowker from the company that bears his name; among other things the company produces Books in Print.

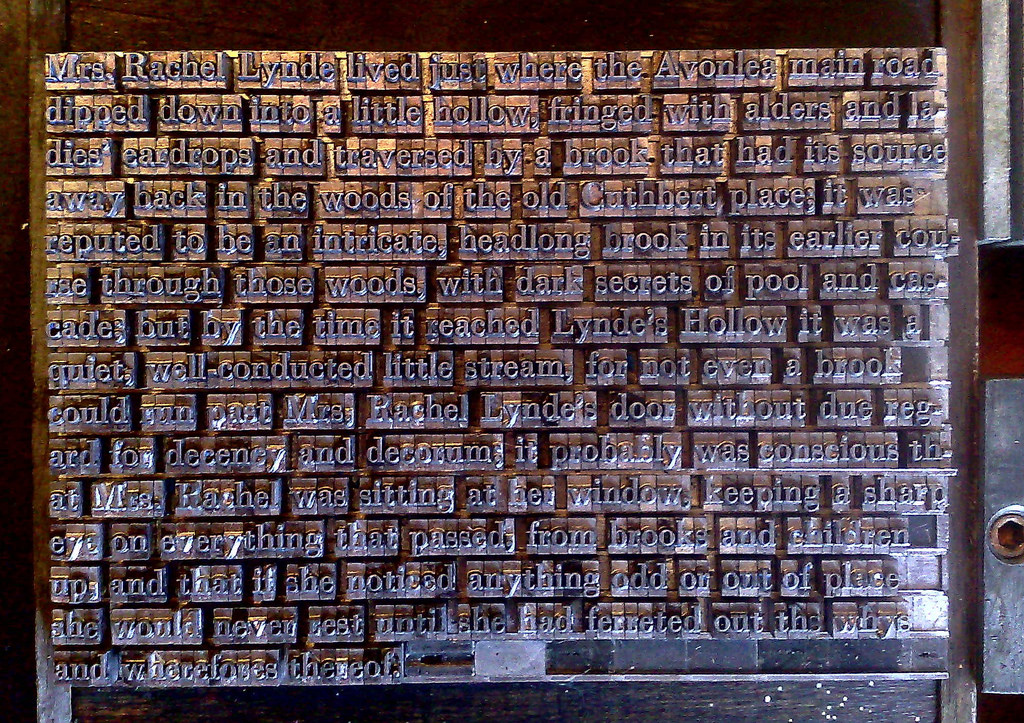

This afternoon I finished setting the type for the first sentence of Anne of Green Gables in Bodoni 12 point. I took a photo of the type in the chase and then digitally mirror-imaged it to allow me to proof it; here’s what that looks like:

I’m still thinking about the ends of each line: as you can see I threw in a couple of hyphenated word breaks to keep the right edge relatively uniform; I don’t think I’ve got it in me to do a full justification, but it would probably be a good exercise to go through.

Once I’d sorted my type drawer, the setting went much more quickly because I could be relatively confident that pulling a given letter out of the drawer would result in that letter being in my hand (before sorting it was a 50-50 chance it would be the wrong letter). The exercise also drilled the California job case layout into my head, so I now find myself almost being able to reach for the right letter without looking at the case layout diagram.

The other lesson learned: my case of Bodoni doesn’t have enough lower case d’s to set much more than this: I only have a half-dozen left over.

Next step: trying printing it.

I am

I am