When we moved into our house on 100 Prince Street in the summer of 2000, the Reid family, from whom we’d purchased it, left a sketch for us on the mantle.

We didn’t know anything about the sketch or the artist until this fall: I noticed that it was signed by what looked to be “John MacGillivray,” and, on a visit to Brìgh Music & Tea a few weeks ago, I happened to ask personable co-owner Mary MacGillivray whether she might be any relation.

“That’s my Uncle Johnny!” exclaimed Mary.

John MacGillivray, it seems, is, among other things, a prolific sketcher of houses, ours among them.

Mystery solved.

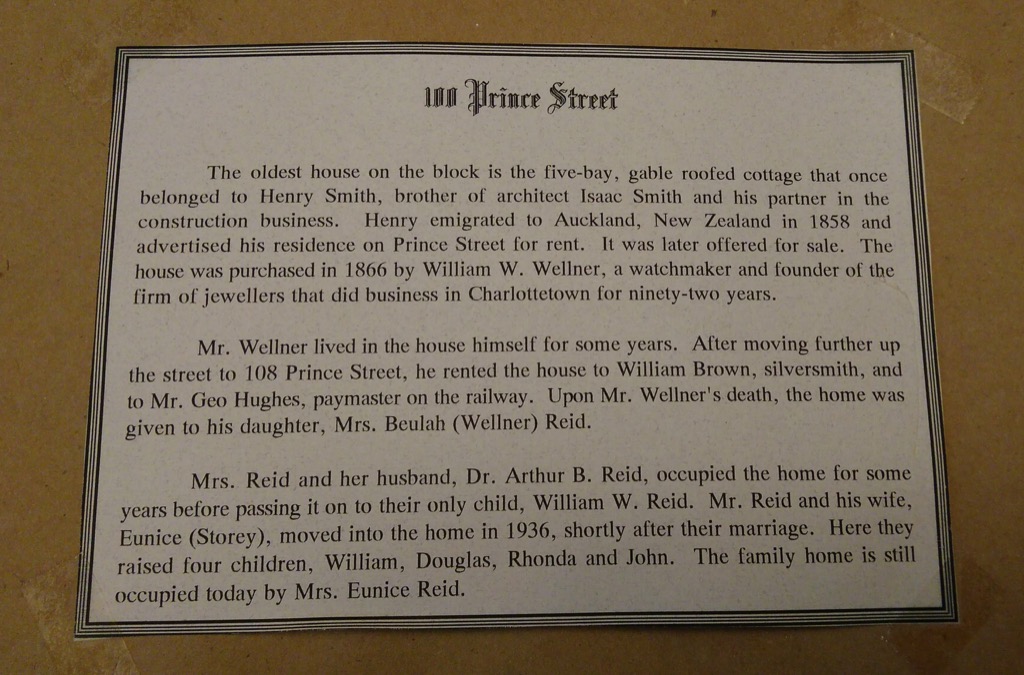

Here’s a thumbnail history of the house–minus us, of course, as it was written well before we moved in–that’s taped to the back of the frame:

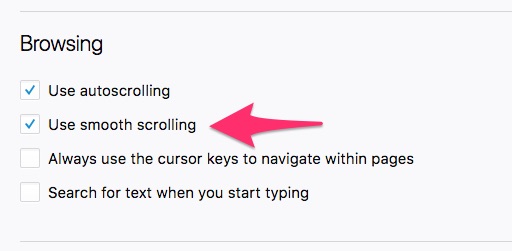

I’ve been a Firefox user forever but I only today learned what the “Use smooth scrolling” setting means:

I’d always assumed this was a setting that somehow “smoothed” the scrolling up and down on a web page as I turned my mouse wheel or used the scroll bar; I thought that without this setting checked the scrolling would be “jankier.”

But today, on a lark, I tried switching it on and off and could see no difference in this regard.

Turns out that’s not what it has to do with.

Rather, here’s how Mozilla’s documentation describes it:

Use smooth scrolling: Smooth scrolling can be very useful if you read a lot of long pages. Normally, when you press Page Down, the view jumps directly down one page. With smooth scrolling, it slides down smoothly, so you can see how much it scrolls. This makes it easier to resume reading from where you were before.

Which is a pretty good explanation of what it does do.

And which prompted me to realize that my keyboard has a key labelled “PgDn” which I’d been ignoring for the last decade (despite, in an earlier era with a different keyboard and a different computer, using such a key all the time).

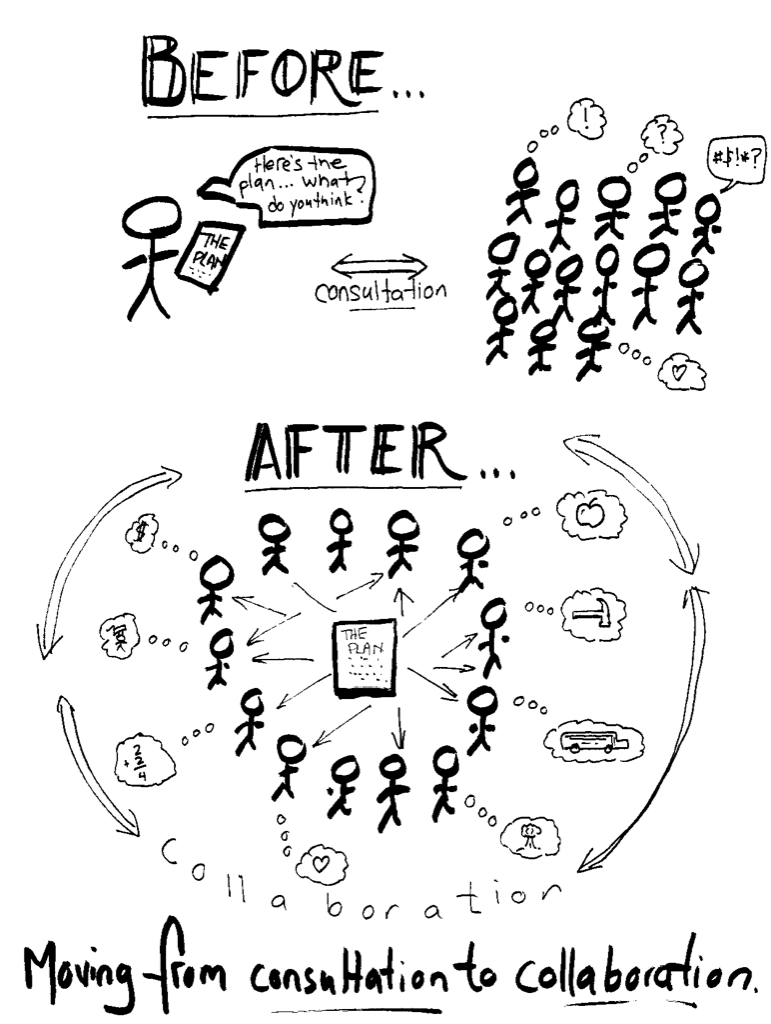

Procrastination–or “just in time planning,” as I prefer to think of it–led me to coming up with a visual to set the scene for last night’s PEI Home and School Federation semi-annual meeting in the late afternoon. What I needed was a way of conveying what we were hoping to achieve: a transition from “consultation” (where government comes up with plans and then asks people for feedback) to “collaboration” (where people are involved in the making of the plan from the very beginning).

I gave designing something a go on my computer, but found it hard to do the concepts justice by assembling bits of other people’s clip art, so I set the keyboard and mouse aside, pulled out a piece of paper and my sketching markers, and drew up something on the fly.

This is what resulted.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

I showed this to Oliver on the way to the meeting, and he immediately understood (which is not surprising, given what he’s taught me about collaboration); this was a good sign.

I hope it worked.

The first source of anxiety for Oliver, starting out this week, was that his regular afternoon educational assistant at high school was going to be off yesterday, and there was, as Oliver put it, some “iffiness” about who would be substituting for her.

Oliver doesn’t like “iffiness,” especially where personnel matters are concerned. This anxiety wasn’t all-consuming–”the situation got resolved,” Oliver told me–but it raised the alert level a little.

On Tuesday morning Catherine got hit with a sudden and unexpected bout of vertigo–”It’s like the worst hangover with out all the fun,” is how she put it on Instagram. Her home care nurse advised staying in bed all day.

Her sudden infirmity threw a spanner into the works of my plan to attend the semi-annual meeting of the PEI Home and School Federation on Tuesday night, as with Catherine in bed, and Oliver’s support worker leaving at 6:00 p.m., Oliver would be left without supper and support. We quickly cobbled together a plan that would have Oliver go out for supper with his support worker before 6:00 p.m., and then Oliver left under the watchful-but-infirm supervision of Catherine-on-bed-rest. Not the perfect solution, but a workable one. We thought.

Late on Tuesday afternoon, I found myself at Central Queens Elementary School helping to set up the sound system for the Home and School meeting (sounds systems are complicated and we found several ways to come close to blowing our eardrums out before we got it right). Once we were set, I checked my email and found a just-arrived message from Oliver:

I miss you, this is too much. Today is too much.

I immediately called Catherine at home, and found that the prospect of an evening off-the-rails was causing Oliver considerable anxiety. She suggested I come home. So I begged out of Home and School hosting duties, hopped in the car, and, 30 minutes later, I was at home with Oliver. By the time I arrived, he’d calmed down considerably, primarily because my impending arrival would help to normalize things.

As it was still daylight, and we both needed to get out of our heads, we piled back into the car, with Ethan the service dog, and headed to the dog park to get some exercise. The dog park was packed with frisky dogs, and Ethan got a week’s worth of exercise in 30 minutes.

When we finished up, I realized that there was still time to get to the Home and School meeting in time for the small group discussions about the future of school planning, and, as students were encouraged to participate, bringing Oliver seemed like a good idea.

We high-tailed it out to Hunter River, stopping to grab a grilled cheese sandwich on the way there, and arrived shortly after the small groups entered conclave.

We found a group to join, 8 people gathered together in a classroom in mid-discussion about greenhouses and real-world curriculum. I interrupted the proceedings to introduce us to the group. And then we joined in the discussion.

Oliver and I have a lot of chats about the difference between consultation and collaboration, and a lot of my ideas about this are informed by things that I’ve learned from him. And so there was a certain poetry to the notion that the fulcrum of the Home and School discussion was exactly that. Oliver was engaged in the discussion, and made several contributions. He was enjoying himself.

At various intervals through the hour that was set aside for the small group work, the moderator of the plenary that was to follow popped in to let us know how much time was left for us–”You have 20 minutes,” he said; then “Just 10 minutes left!” and so on.

One of the things that really, really triggers anxiety in Oliver is ticking countdowns: he finds it incredibly stressful to be hurried along and rushed, especially when he’s as engaged in an activity as he was in the discussion, and especially when he’s already had a stressful day. He was able to keep his anxiety contained while the discussions were going on, but as soon as they came to an end his anxiety boiled over, and he lapsed into a full-fledged meltdown.

This involved a lot of yelling, a lot of flailing of fists, and some toppling of chairs. To someone unused to witnessing this, I expect it would have been quite distressing.

It took Oliver about 10 minutes to calm down enough to the point where we could communicate, and about 10 more minutes to get to the point where we could safely, calmly leave the school.

We stopped on the way home to get something for Catherine to eat, and by the time we arrived home around 9:00 p.m., Oliver was relaxed and feeling a little better.

On the way two bed, an hour later, he’d had time to reflect on the day and on the evening, and was very intent on making it clear that he was “disappointed in his actions.” We had a long chat about what had happened, and how it wasn’t his fault, and about steps we could have taken along the way to mitigate the trigger (like asking the moderator, after the first pop-in, to stop the countdown and the rushing).

While the evening’s proceedings were stressful for Oliver, and stressful for me, having meltdowns isn’t unusual for Oliver. It’s not something that happens every day and, indeed, often weeks or months can go by without one. But it’s familiar territory for us.

What was novel for Oliver about last night is that this all played out on a very public stage; that’s why, I think, Oliver was more than usually disappointed–he’d broken down in front of a group with which, only minutes before, he’d been actively engaged.

What was novel for me about last night was that, over the following minutes and hours, I received about half a dozen text messages or emails from friends and acquaintances who were at the meeting, both checking in to see how we were and expressing some confusion about how or whether they could have helped.

So, in addition to everything else, this blog post is by way of answering that question, and providing some context to those people.

Here are some things to understand that might be helpful in future:

- When Oliver’s in the throes of a meltdown, and is lashing out and hitting and yelling and toppling chairs, this isn’t an expression of violence, it’s an expression of anxiety. It’s less “bar fight” and more “utterly overwhelmed.”

- When Oliver’s in the throes of a meltdown, he cannot hear. It took me a long time to figure this out, but Oliver’s good at describing it now: his senses shut down, and when I’m saying “everything’s okay Oliver, calm down,” he’s hearing “blah blah blah blah blah.” So, in the thick of it, there’s little point in doing anything other than working to keep him and others safe. It’s not the time for reasoning.

- It takes a while to fully recover. I know Oliver’s breathing and facial expressions well enough to know where he’s at in the meltdown rise and fall; after the room had cleared, and he was sitting down, he still couldn’t hear me. It took 10 minutes of calmly sitting together before we could have a conversation of any sort.

- Having a meltdown is exhausting for Oliver: it’s like running an emotional marathon in 10 minutes.

- When Oliver’s in the throes of a meltdown, I’m 100% concentrated on keeping him and others safe. Which means that, in a way that ironically parallels Oliver, I’m not focused on anything else, and I likely can’t see or hear you if you’re talking to me. I have very little memory of the height of last night’s meltdown, and couldn’t tell you how many other people were in the room or what they were doing.

- In general, I don’t need help. Introducing new people into the mix would only complicate things for me and for Oliver. If I happen to lose track of Ethan, grabbing his leash and keeping him out of harm’s way is a help. But, other than that, we’ll make our way through a process together, Oliver and me, and we’ll come out the other end of it.

- Reaching out to inquire about us after the fact is very helpful and supportive; having a meltdown is all-consuming for Oliver, but it’s also a parenting challenge, and simply being reminded that there are other people in the world, when we’re calming down, is a big help.

Oliver woke up this morning in a good mood, and, reflecting back on last night, he told me that “he enjoyed the creative part, just not the rushing part.” Thank you to the members of our group who welcomed him in and allowed him to participate as an equal in charting the course of how we plan public education; it meant a lot to him, and to me.

In the car ride home from Central Queens last night, I told Oliver that he didn’t have anything to be ashamed about: he wasn’t “bad” for having a meltdown, it’s just how his brain works sometimes.

“You tell me this every time this happens,” he told me, and a tone that conveyed resignation and appreciation both.

And it really is just the way his brain works. Some people are musical, some people don’t like spiders, some people have challenges reading, and some people freak out when they’re rushed. The best thing we can do is to learn from what’s happened, get better at mitigating the triggers and shepherding the process.

And helping our friends and family and community to understand that this is simply the way that things work for us. It’s our normal.

And so while Oliver might be disappointed or embarrassed about his actions on a public stage, perhaps there’s a silver lining that others, by virtue of that stage, get to understand a little more about Oliver and how he works.

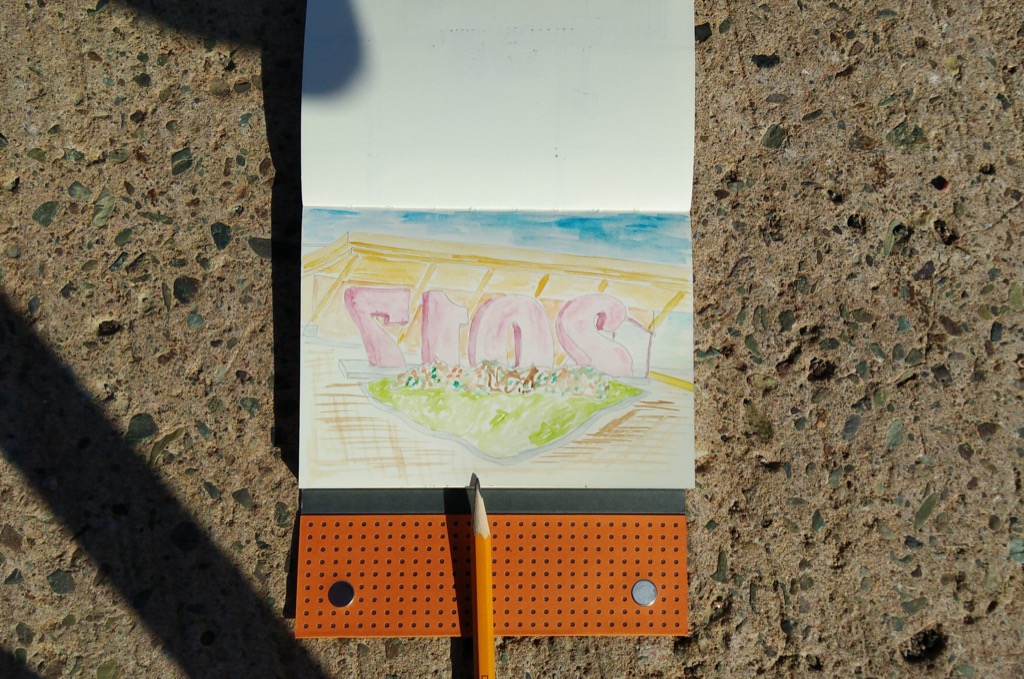

It was a bright sunshiny day today, and so, after lunch, instead of walking back up Queen Street to the Reinventorium, I walked down Queen Street to the Coast Guard wharf. Where I found a gaggle of cruise ship tourists taking selfies in front of the 2017 sculpture.

I set myself down behind them all, on an Adirondack chair chained to the wharf and facing the harbour, a chair I turned around to face the 2017 and the Milton Acorn Convention Centre, and sketched the 2017 from behind.

The sun and the sea and the wind conspired to do something interesting to the paper and paint, so the result was something significantly more traditionally watercoloury than I’ve been able to achieve previously.

Forty-five years ago today, Peter Gzowski, hosting This Country in the Morning on CBC Radio, met Robertson Davies for the first time.

The interview, a transcript of which appears in Conversations with Robertson Davies, begins:

PG: I welcome now, with great pleasure, Robertson Davies, a man whom I’ve been reading for years and have not had the pleasure of meeting until this morning, and the first question I had to ask him as he arrived in the studio was “How does one address the Master of Massey College?” because my experience with that title is almost totally from the novels of C. P. Snow where people are always calling one another, or calling the master “Master,” but you don’t say that outside the college?

RD: Well no. It’s silly, I mean it implies particularly, I think, to Canadian ears, a type of superiority which I would not dream of [chuckles] assuming and it’s just that I don’t like Principal or President or Provost or whatever it was, and I was called the Master of Massey College because it was one of the few academic titles left when I got there.

Later in their conversation they are joined by the psychiatrist Vivian Rakoff, from the Clarke Institute, and the topic turns to coincidence, something that lurks as a constant theme in Davies’s work:

VR: You know, I would be very stupid to reject what you say out of hand because I think that much of what you say is true, and one has after all, only got to see in one’s own life the kind of novelist’s devices at play, the coming together by accident of things that you just wouldn’t have dreamt of, and I often find myself saying to someone that coincidences are so colossal that they would be rotten in a novel.

RD: Yes, yes. Exactly.

VR: Or you know, when one is in a personal situation, and one says gawd, this is badly written because it’s so trite, because literature reflects back, and yet, I must persist with as much politeness as I can that one of the devices after all in the novel is to prevent this coincidence, coming together too neatly, appearing to resolve too quickly. Oddly enough, the novelist, and particularly a fictive account of a life, has to be much more—here I am teaching my—to put it mildly—my grandfather in all sorts of ways to suck eggs—but it would seem to me that one of the technical problems in reporting a life is in fact not to make it come out too neatly.

RD: Yes.

PG: So you can’t have reality.

VR: That’s precisely it. That in fact you know Francis Bacon, the painter, for example, when he’s finished something that looks too real, goes across and quite arbitrarily just scratches up the surface because the paradox is that reality is the enemy of that necessary enclosed world which is a work of art.

RD: Yes. I think you’re entirely right. Shakespeare says something about that in one of his plays. Someone says if this were presented upon the stage now, I would condemn it as an improbable fiction and it is true that if you want to present life as an effective sort of realistic representation of life, you must not be so daring about coincidence as fate is. But Jung wrote so interestingly about this in his theories about synchronicity, and so forth, that I have been greatly tempted to have a bash at it [Laughs].

That bash is what so drew me to Davies in my twenties, where I essentially stopped my studies and sat down to read his entire canon.

Vivian Rakoff’s son was David Rakoff, someone you might remember from This American Life.

Ira Glass memorialized the younger Rakoff, who died five years ago, at age 47, in an episode of the program produced shortly thereafter; Glass began:

One of the first times I met David Rakoff— this is before he started writing stories for the radio— he invited me to sit in the window of a department store with him. He was playing Sigmund Freud in a Christmas display window at Barney’s, and he was seeing patients in the window. David sat in a chair. I lay on a couch.

My mom was the therapist. David’s dad was a psychiatrist. We’d both been therapy patients ourselves at some point or another. And so it was easy for us to play this simulacrum of psychiatry with each other. I don’t remember what we talked about. It was so long ago. But I remember very clearly the feeling of it.

David, gently asking leading general questions like a real therapist would— how are things going? Why do you think you said that? It was easy to talk to him. And unlike the real Sigmund Freud, he offered advice. And it was surprisingly cozy.

Though one wall of the room that we were in was this plate glass window that faced Madison Avenue, the space was narrow and cocoon-like. The muffled street noise that leaked through the window made it feel more womb-like if anything. People on the street couldn’t hear what we said to each other. So it was both public and intimate. I left feeling close to him. I left wishing we could do it again.

And we did, in a way. Nearly everything he ever made for our radio show was a personal act, made in close collaboration for public consumption, performed behind a plate glass window of one kind or another. This week marks the fifth anniversary of his death. He’d been on This American Life 25 times. The first time was in 1996, just two months after we went on the air. The last was just three weeks before he died.

Also from Conversations with Robertson Davies, here Davies addresses death, speaking with Tom Harpur:

Robertson Davies: By preparation for death I don’t mean folding your hands or going around forgiving a lot of people you don’t want to forgive: it’s preparing for a richness, a good and glorious end.

Tom Harpur: But how does one prepare?

Robertson Davies: You have to come to terms with yourself and your place in the scheme of life – something a good many people don’t want to do. In the last century we have extended the normal life-span. Many seem to believe that this means we have extended the period when they should enjoy the things they enjoyed in youth. But, I don’t think they realize that we’ve also expanded the period of life when we can learn to think, feel, and experience the largeness and splendor of life.

Oliver recites the poem We are here, turning the mundane into the delightful.

On the GO Train westbound to Burlington, we passed within spitting distance of the CN Tower. With my phone in selfie mode, I angled it at 45° to the window and hoped for the best.

I am

I am