The Autism Secretariat Act will be debated tonight on the floor of the Legislative Assembly. I’ve been invited by MLA Sidney MacEwen, who put forward the bill, to join him on the floor as a “stranger” when the the Legislative Assembly moves to consider the bill as Committee of the Whole House.

I encourage you to attend the proceedings in the public gallery tonight if you are able, or to tune in to the live stream if you are not. The evening sitting starts at 7:00 p.m.

The Spanish Prisoner, David Mamet’s 1998 film, remains one of my favourites. The movie has a stellar cast that includes Campbell Scott, Steve Martin, Rebecca Pidgeon, Ben Gazzara, Felicity Huffman and Ricky Jay.

Ricky Jay died on Saturday, at the age of 72. The Spanish Prisoner was my first exposure to him, so I knew him as an actor before I knew him as a magician. That was corrected in 2002 when, at the insistence of my friend Dave, we took in his show in New York City.

I was a true fan. He will be missed.

My father’s father was born in Konjsko Brdo, Croatia in 1903; he left for Canada in 1926, and sometime after that my great-grandfather’s family relocated to Dišnik, in northeastern Croatia, a village just north of the city of Kutina.

This fact of my ancestry explains why I’ve visited this small town of some 20,000 people that you’ve never heard of. Twice.

The first time was in October 2004 when my father and I visited as part of a father-and-son exploration of our Croatian roots. At the time we didn’t know of our family’s pilgrimage from Konjsko Brdo, and we’d been led to the area on the off chance that we might locate my father’s cousin Regina Arace, who was rumoured to live there. We didn’t find Regina (although we found her house), but we did find my father’s last surviving aunt, Manda, and her husband Iva Baretic, living in a small house nearby. As I wrote at the time, this was a huge surprise, as we’d no idea that my grandfather had younger siblings:

By some miraculous series of events that involved a trip to a bookie, a trip to the police station (for information, not arrest), and about a dozen extremely helpful Croatians who sent us “up the hill, to the right, until where the pavement ends and you come to a vineyard,” at 4:00 p.m. we found ourselves driving our little Renault down a rough country lane towards a fedora-wearing man leaning on a fence. Dad asked, in his best Croatian, “can you direct us to Manda´s house?”

“This is Manda´s house!” was his response. We had found the house of my step-great-Aunt Manda and her husband Ivo. Manda’s father Stipe is my great-grandfather. We were invited into their humble farmhouse, fed a meal of cured ham and whisky (Dad drank the whisky — I was driving), and Dad pulled off an amazing facsimile of a native Croatian speaker to engage them in conversation about family connections, family history, and their life.

Here’s a photo of Manda, my father, and Ivo:

And here’s me and Manda and her dog:

The experience of discovering long-lost family is and will remain one of the highlights of my traveling life, and, I think, of my father’s as well.

That evening, eager to go back the next day for another visit, we booked a room at the Hotel Kutina, in the nearest town that had a hotel.

The next day we did, indeed, go back, bringing gifts and engaging in some more catch-up about the previous century. And then we were off south, where even more family discoveries awaited us.

Six years later, in December of 2010, I went back to Kutina, this time with Oliver and Catherine.

Our trip had started in Munich, continued to Basel, then Venice, Ljubljana and finally Croatia. We booked ourselves a room at the same Hotel Kutina; it was colder in December than it had been on the first visit in October, and the hotel, if memory serves, was either missing hot water or heat. Or maybe both. But at least there were blankets:

Here’s Oliver and Catherine in front of the hotel:

The next day we went in search of Manda and Ivo; I was eager to introduce Oliver to his great-great-Aunt and her husband, and for Catherine and Oliver to see something of rural Croatia.

To our dismay, while visiting the graveyard in Dišnik we found Ivo’s grave; there was no grave for Manda, however, and we were hopeful that she was still alive.

Through a rather miraculous and circuitous connection involving the Peruvian branch of the Rukavinas, we were able to find Manda in a Red Cross-Red Crescent nursing home nearby. Here’s a photo of Manda and Oliver:

It was a challenging visit: we spoke no Croatian, Manda spoke no English, and by this time she was in advanced stages of dementia. But we all tried our best, and I think the visit brought a little light into all of our lives.

Again bidding farewell to Manda and leaving greater Kutina, we too headed south for more family adventures.

This is all a very long-winded preamble to a brief note that Kutina achieved some small measure of fame in the latest telling of John Le Carré’s The Little Drummer Girl.

In episode 3, Charlie, played by Florence Pugh, is driving a Mercedes from Greece to Austria, and stops in Kutina for the night. She stops at the Hotel Glavina, a hotel that, as far as I can determine, is fictional.

Here’s an (audioless) clip showing Charlie’s arrival in Kutina, and her meetup with an undercover agent:

They go on to play a short game of Scrabble by way of communicating secrets to each other.

One minute and twenty-one seconds of the episode are set in Kutina.

(If you liked this post, check out William Denton’s rigorous cataloging of the appearances of libraries in Archie comics).

The Guardian published a guest opinion piece I wrote on The Autism Secretariat Act, which received first reading in the Legislative Assembly this week.

This bill is a reasonable and straightforward call for the establishment of cabinet-level responsibility for autism; I believe that it’s a small step in the right direction toward coordinating programs and services for autistic Islanders.

It’s been an odd experience to be invested in the passage of a bill to this extent, and I’ve spent a lot of my time this week reaching out to MLAs to try to explain why I feel this way, and to ask them to support the bill.

It’s also odd, of course, to be supporting a bill or forward by a Progressive Conservative member when I’ve no affiliation with the party; but politics, as they say, makes strange bedfellows, and I believe PC MLA Sidney MacEwen has put forward the bill for all the right reasons: he’s talked to constituents, distilled a problem from what they’ve told him, and is proposing a change to address the issue.

I think the plan is for the bill to receive second reading on Tuesday evening; I am hopeful that it will receive all-party support and move forward.

Every morning during the school year I drive Oliver from our house to Colonel Gray Senior High School, a distance of 1.74 km one-way.

Oliver sent me a link to Mission Emission this morning, a calculator for vehicle emissions, and I used it to determine the emissions from this daily school run, which it calculates are 537g of CO2.

Doubling that–because I drive back home immediately afterward on the same route–gives me a figure of 1074g of CO2 per day, or, over 180 school days, 193 kilograms of CO2 per year.

If Oliver and I were to bicycle to school instead of driving, our daily impact would go from 1074g of CO2 to 20g of CO2, which is a dramatic decrease to 3.6 kilograms per year.

Walking to school would achieve a similar although slightly less impressive result, lowering our impact to 7.9 kilograms per year.

Of course, as with all discussions of emissions and climate change, the invisibility of CO2 and the attendant difficulty in imagining what these numbers mean in real terms in our daily life is part of the challenge of behaviour modification: in this regard I found the recent IPCC report incredibly motivating, as it calls for net-zero by 2050, and net-zero emissions is something I can wrap my head around.

Moving from 193 kg of CO to 3.6 of kg is getting pretty close to net-zero: it’s a 98% reduction in emissions for our school run.

This documentary short tells the sad and yet somehow delightful story of the famous IKEA photograph of Amsterdam that appears on walls all around the world.

Filmmaker Tom Roes tracked down the brother of the late Fernando Bengoechea, who took the photograph, and learned the story of how the photo was taken, and how it came to be acquired by IKEA.

The intersection of private detective work, journalism, film-making and YouTube can be a very interesting place indeed.

There’s a little more of the story in this blog post by Roes (and if you’re English-speaking, be sure to turn on subtitles when you watch the documentary).

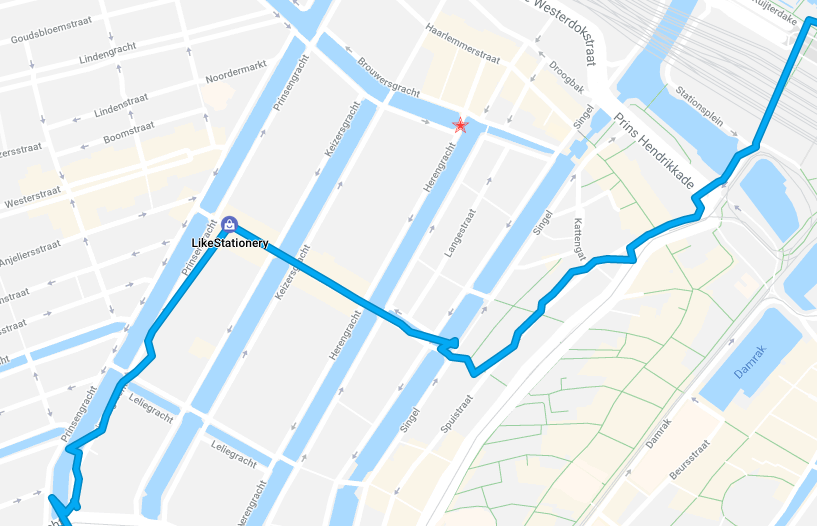

It turns out that when Oliver and I were in Amsterdam in early September we came within a block of the location where the photo was taken; here’s my Google Location History for September 3, 2018, with a red star showing the location near the intersection of Brouwersgracht and Herengracht:

Because this autumn wasn’t already exciting enough, fates connived to cause our roof to start leaking last month. We got by with a temporary patch job and a fleet of buckets in the attic, but the fall rains got the best of us, and I feared a completely meltdown come midwinter or spring thaw.

Fortunately, by some miracle of scheduling and logistics, MacBeth Bros. were able to squeeze in our job last week. Their crew is dynamite: they threaded the needle of roofing through the rain and snow and sleet and they got it done: the front roof went up on Tuesday, the back roof on Thursday, and the vestibules on Friday.

We’ve got more infrastructure work ahead of us this fall, as the roof worked showed up some issues with our chimney, and we have a longstanding job to insulate the attic that we really need to attend to. But we’ve made a good start.

The aforementioned fates, seeing that we’d taken control of things, decided to up the ante and caused our upstairs toilet to leak, which damaged our kitchen ceiling; fortunately this was covered by our PEI Mutual insurance policy, so this work was quickly attended to and the paint went up on the kitchen ceiling on Friday.

In the grander scheme of things we have nothing to complain about: we can afford to pay the bills, we have food on our plates and hot water in our radiators, and we’re ready to take on the winter.

How did I not notice this URL before, an homage to one of the great television characters of all time.

O’Reilly Radar is now O’Reilly Ideas, which is way, way less fun.

In Political Studies class this week, Oliver is learning about the differences between the economics spectrum and the political spectrum. This post from Stephanie Booth was a good jumping off point for our own discussion about this:

Ce matin, dans un podcast un intervenant remarquait que l’on avait été tellement bien éduqués à être des consommateurs qu’on réagissait en consommateurs et non en citoyens aux problèmes politiques ou de gouvernement. Je pense que c’est une remarque très juste, et que c’est grave. On ne résout pas les problèmes politiques en agissant comme des consommateurs mécontents.

In 2014 when I presented, on behalf of PEI Home and School Federation, to the Standing Committee on Education, during in the question and answer period with MLAs afterwards, I said “The education system is not Walmart,” and it’s this “We do not solve political problems by acting as dissatisfied consumers” sentiment that I was trying to convey. We are not customers of the public school system, we are actors in it, co-conspirators in the process of educating ourselves, all of us, as citizens.

Oliver rambling about the roof of the Duomo in Milan when he was 7 years old. It was an ethereal autumn day: crisp, bright, and foggy. On a remarkable building.

I am

I am