Thanks to the assistance of Dan and Steven I was able to identify a problem with the RSS feeds from this server.

Technically the problem was with the newsreaders (in Steven’s case Straw and in Dan’s case NewzCrawler), not the RSS feed itself. I turned on gzip compression on my Apache server about three weeks ago to preserve bandwidth. In theory, user-agents like web browsers and RSS readers should be able to either send a “Accept-Encoding: gzip” header and accept compressed data, or, if they don’t, be sent the original non-compressed data.

Somehow this mechanism was causing problems for Steven and Dan and their RSS readers (although it didn’t affect NetNewsWire, which is what I use). For the time being, I’ve turned off compression, and this appears to have solved the problem.

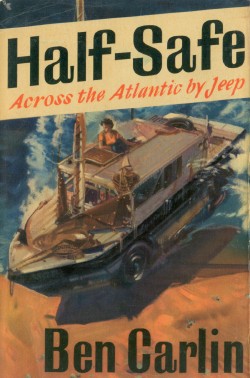

In the summer of 1950, Ben Carlin and his wife Elinore left Halifax, Nova Scotia in a World War II amphibious jeep, nicknamed Half-Safe, bound, ultimately, for Birmingham, England. Carlin’s book Half-Safe: Across the Atlantic by Jeep is the tale of their journey.

In the summer of 1950, Ben Carlin and his wife Elinore left Halifax, Nova Scotia in a World War II amphibious jeep, nicknamed Half-Safe, bound, ultimately, for Birmingham, England. Carlin’s book Half-Safe: Across the Atlantic by Jeep is the tale of their journey.

Unique among “voyage around the world” books, reaction of my friends and family upon hearing me summarize Half-Safe’s voyage was, more often then not, to deny that such a voyage was possible. Indeed the Carlins found the same problem during their voyage, and sometimes found it difficult to get the publicity and sponsorship their voyage deserved.

But it is true: Half-Safe, a souped-up amphibious Ford jeep, purchased surplus after the war near Washington, DC, carried the Carlins on land and on sea, and therein allowed them to work around the usual need to “ship the Land Rover across the Atlantic and then pick up the trip” that characterizes most if not all other round-the-world expeditions.

The impetus for the trip was, like most others, the result of a dare. Carlin, an Australian, was in India during the war working as a Field Engineer. He relates in the opening chapter, still in India at the close of the war in 1945:

With my opposite number in the Air Force, Squadron-Leader M.C. Bunting, OBE, RAF, I was inspecting installations on the deserted field and had no business looking at vehicles, but a battered amphibious jeep caught my eye. I have always been interested in salt water, small boats, and vehicles and fancy I know something about them all. After fifteen minutes around, over and under this oddity of which I had heard but never before seen, I mused, as much to myself as to him, ‘You know, Mac, with a bit of titivation you could go around the world in one of these things.’ Mac was a very polite, sober and laconic character. He said, ‘Nuts!’

It took Carlin five years to get to America, locate, modify, test and refine the jeep, find and marry his wartime sweetheart, and make his way to Halifax for departure.

Halifax did not fare well in the eyes of the Carlins:

This is as good a time as any to pay a tribute to Halifax — the finest departure point anyone ever had. I’d gladly leave Halifax any time for anywhere in anything. The city glows with the same rich, warm flame of enlightened liberalism which lit medieval Aberdeen. In two years there, we entered only seven private homes, not more than two of which we are likely to see again.

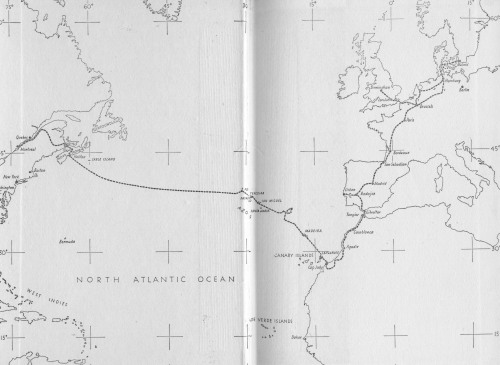

Once the major voyage-ending bugs were worked out of Half-Safe’s systems — and there were a large number of them, mostly involving different methods for carrying fuel — the Carlins set off for the Azores from Halifax on July 19, 1950.

Their plan was to head for Flores; they arrived there 32 days later, having travelled through a hurricane, the jeep pummelled almost to the breaking point, having suffered tremendous seasickness (especially Elinore) and, one would imagine, testing their marriage severely.

From the Azores they steamed to Madeira, and then made land at Africa at Cap Juby before driving overland through Agadir, Casablanca, Gibraltar, Lison, Madrid, Paris, Brussels, Denmark, Sweden, London and finally Birmingham, where they arrived on New Years Day, 1952.

Despite their adventures at sea, the voyage overland was perhaps more challenging that the one over sea, mostly because of the variety of borders to cross, breakdowns of the jeep, and the need to hold shows to raise money to support the trip.

The Carlins weren’t rich, and although there was some sponsorship from a North American magazine, and the promise of more from other sources, not more than once they were down to their last dollar and had to pawn their movie camera, or sell surplus fuel to continue on.

Carlin is a witty writer, and the book is a rollicking good tale of adventure, and contains considerable technical details of their voyage.

While the voyage the book relates ends in England, Carlin did, in fact, continue onwards from there, and this helpful Australian website contains a brief summary of that voyage. The tale of this second leg of the voyage is available as The Other Half of Half-Safe, which can be purchased from Carlin’s alma mater, Guildford Grammar School, which has a page devoted to Carlin’s adventures. The school is also the final resting place of the jeep Half-Safe where it is, says the school, “displayed prominently within the grounds.”

Interestingly, Carlin’s second voyage took place at the same time as the Oxford and Cambridge Far Eastern Expedition, although, as this commentator notes, “So, there were two overland expeditions in southern Burma at the same time. Both expeditions wrote up their adventures, yet neither mentions the other.”

Carlin continued on around the world, and ended up back in Montreal on May 12, 1958, almost eight years after starting out.

I purchased Half-Safe used from a bookseller in the U.S. using abebooks.com. It is out of print, but many other used copies are available for sale there.

My friend Ann asked me last week if I had a particular issue of The New Yorker from last fall, as a friend of hers suggested that she read an article therein. I looked and looked, and could never find this article and so ended up dumping all of my fall issues on Ann’s doorstep on Saturday night with hopes that she would be more successful.

This morning, on a lark, I went to the PEI Provincial Library Online Databases page, entered my library card number, searched the “General Reference” database, and found the text of the article, in its entirety.

I’ve mentioned this resource before, but it bears repeating: you’ll find a lot of “offline” resource hidden in those databases, and as our PEI tax dollars have already paid for access to them, we might as well take advantage of them.

And next time you see Harry Holman, give him a hug.

Here’s a bit of helpful advice from Nintendo regarding parental oversight of GameCube-playing children:

Parents should watch when their children play video games. Stop playing and consult a doctor if you or your child have any of the following symptoms:

- Convulsions

- Loss of awareness

- Involuntary movements

- Eye or muscle twitching

- Altered vision

- Disorientation

In April of 1988, in a somewhat irrational move, I went to the Humane Society in Peterborough, Ontario and got myself a dog.

The move was irrational mostly because I was living with three roommates in a smallish apartment, the dog in question not house trained, and two of the three roommates were in the middle of final exams. Suffice to say that a lot of things that weren’t supposed to get peed on did get peed on, and I stretched the roommate patience boundaries to their limits.

It was also irrational because, although we had dogs growing up, I knew next to nothing about real life dog care, especially when living in a city. And I had certainly never trained a dog before.

The dog I choose was named Penny. Although I would never name a dog Penny myself, I considered it bad luck to change her, so Penny she stayed.

Penny was born in Scarborough. When she came into my life she was 4 months old, and, to be charitable, was somewhat “out of control.” Although I never learned Penny’s back story, I always attributed birth in Scarborough, and the mysterious journey to the Peterborough Humane Society, as the cause of her mild insanity, and tried very hard never to hold it against her.

At the end of the school term, after everything that could be peed on had, we roommates went our separate ways, and I moved into an abandoned house at 107 Hazlitt Street in Peterborough’s left-bank “East City” neighbourhood. The location was perfect for Penny, as the house fronted on 25 acres of park land on the banks of the Otonabee River, giving her plenty of room to roam wild and free and live an almost country-dog existence.

It was over that summer that, despite my attempts to steer her on the right path, Penny gained a reputation as an irascible dog.

Some of this was deserved, of course: she, somewhat famously, ate the Birkenstocks of my friend Stephen, who became my roommate on Hazlitt Street shortly after Penny and I moved in.

And I do recall her eating, among other things, a pound of butter and several heads of broccoli.

On the way to Division St. Fish and Chips in Kingston she did jump out of the moving car, albeit at low speed and suffering no ill effect as a result.

It must be said, to Penny’s credit, that summer was one full of various self-administered intoxicants, so some of her whacky behaviours might have been imagined or at least exaggerated.

The one thing Penny never really learned to do under my watch was to come when she was called. I tried, oh I tried. And I did develop several tricky maneuvers that involved throwing sticks into the waiting Datsun 510, with hopes that a deluded Penny would bound in to fetch them, only to be trapped by a quick close of the car door.

These maneuvers were made somewhat easier by Penny’s primary behavioural characteristic which was a love of the fetch. Penny was a Lab-Spaniel cross. And although she had the size and ears of a Spaniel, the Lab parts of her brain won out. She would fetch anything. Endlessly. I never, ever saw her get tired. The look on her face during a good long throw-fetch session was one of pure grace and contentment. Indeed it was her proficiency at the fetch that, if not won over, at least drew some of her doubters away from the brink.

There are three episodes from Penny’s early years that further draw a picture of her unusual nature. The first occurred on Heydon Island, the Muskoka retreat of my good friends George and Leslie. Penny and I were invited to spend the week at Heydon Island that summer. For Penny, who revelled in being let to run free, Heydon Island was a paradise: I literally let her loose when we docked on the first day, and collared her only when it was time to leave.

On the morning of the second or third day, I woke up around 7:00 a.m. and found Penny, who despite her wild and free Island days would always find me to sleep near, nowhere to be found. Thinking that perhaps she had decided to make an early day of it, I got up and headed off to the “dip dock,” a small wooden dock on the deeper-water side of the Island that George and Leslie’s son Stefan called the “dip dog” because of Penny’s delight in jumping from it.

When I got to the dip dog, I heard Penny, whimpering quietly. But I couldn’t locate her. After some searching, eventually I realized that she was under the dip dog: somehow she had managed to jump off the dock, and then swim underneath, but the waves lapping against the dock prevented her from extricating herself. I summoned George, and together with the help of a crowbar, we managed to pry off one of the dock’s planks and free Penny. She bounded up out of the underworld and went off running to play some more.

The following summer, my girlfriend Mary Clare and I headed out west for several weeks. We decided to stop for three days in Winnipeg to take in the Folk Festival. We arrived there at about 3:00 a.m., exhausted after a drive straight from Thunder Bay. We quickly set up our tents and, unable to constrain Penny and Sam (Mary Clare’s dog), we let them out of the tent to play amongst themselves through the night.

When we woke up the next morning, we found that Penny (and it surely was Penny, as Sam was never devious) had made a night of wandering around to other campsites and gathering for us things she thought might be useful: there was a nice lower-lumbar support cushion for the car, a plastic water bottle, and several other items. We had no choice, of course, but to keep these items, as they could have come from anywhere. If we had wanted, Penny and I could have hacked out a very lucrative life of crime together.

The next summer, I was working at Trent Radio and, because of a kind manager, Penny was able to come to work with me most days. One day I working downstairs in the studio, having left Penny to sleep upstairs in our second floor offices. The phone rang. It was someone calling from Tom’s Square Pizza across the street. “Do you know that there’s a dog on your roof?”, they said.

It seems that Penny had woken up and decided that the open window, which led to a gently sloping roof, was too good an opportunity to pass up. So she leaped onto the desk and out the window onto the roof. Where she was spotted by our helpful neighbour. By the time I’d gotten the phone call and hurried outside, she had miraculously made it down from the roof into the yard, which would require a brave leap of perhaps 12 feet down.

Midway through our second summer together, I decided that Penny needed to be trained. While her antics were sometimes hilarious, I was concerned that, left to her own devices, she would do harm to herself or others. So Penny and I signed up for classes with Fred Primeau, professional dog trainer.

For reasons I cannot recall, my car wasn’t working at the time, so Penny and I actually had to hitchhike to Fred Primeau’s for our weekly sessions, which was always a challenge, especially in the rain.

If I had ever doubted the usefulness of professional dog training, Fred Primeau disabused me of all doubt. While it’s not quite accurate to say that Penny was a “changed dog” after our 7 or 8 sessions, the training did have a rather dramatic effect on both of us (I’ve always maintained that Fred actually training the people, not the dogs). Even some of Penny’s greatest critics noticed the change in her behaviour and “controllability,” and day to day Penny-management became much easier for both of us.

The most dramatic event ever to befall Penny and I occurred our last spring together. I was headed off on vacation somewhere, and Penny wasn’t able to come with me, so my friend Oonagh graciously agreed to look after her while I was gone. When I returned from vacation, and went to pick up Penny, Oonagh invited me in for tea, and we let Penny out in her back yard to play.

About 20 minutes later I heard the most terrifying shriek from the street in front of Oonagh’s house, which I immediately felt in my gut was Penny. We ran outside to find a huge American car ground to a halt on the street and a very shaken man getting out to see what he had hit. I was shaking myself.

We leaned down simultaneously to find Penny, splayed on all fours, pinned beneath the engine. She was alive, and looking quite shocked. Fortunately for all concerned, a helpful truck driver stopped at that moment, whipped out a car jack, and jacked up the car. Penny stood up, shook herself off, and walked over to us, apparently none the worse for wear.

The driver of the car was, as you might expect, considerably relieved, as were we. We rushed Penny to the vet to ensure no internal damage had occurred, and found that, in the end, short of a small cut on the lip, she was in fine form.

Which was about as close to a miracle as I’ve ever seen.

Later that year, I had an opportunity to go to El Paso, Texas for several months to care for George and Leslie’s Stefan. As much as I would have liked to bring Penny along, it quickly became evident that wasn’t going to work. Fortunately, my old friend Lorna happened to have just returned to Peterborough, and volunteered to care for Penny while I was gone. As Lorna and Penny had always gotten along quite well, I knew Penny would be in good hands, so off I set.

While I was in Texas, Lorna got an opportunity to move back to the British Columbia, and, not wanting to shirk her commitment to me, took Penny with her. The plan was that, on my return from El Paso, I would swing up through BC and retrieve Penny.

As things turned out, I ran out of money and needed to make a mad dash for Montreal, which was to be my new home, and couldn’t rendezvous with Penny. Although we developed several tentative plans otherwise, it became apparent over the next months that Penny was going to stay with Lorna in the west, which proved, in the end, to be best for Penny, Lorna and I (although I can’t say that I didn’t miss her terribly for long after).

And so, over the next years, Penny switched from being “my dog Penny, who Lorna’s looking after” to “my old dog Penny” to “Lorna’s dog Penny.”

Lorna moved several times after that and, as coincidence would have it, ended up moving to Prince Edward Island several years ago with her new husband and two kids. Catherine and I went out to visit them several times, and I was able to see Penny again, now a sort of “elder statesdog,” still eager for the fetch and able to go, go, go all day but, said Lorna, reconciled to paying for this with an arthritic recovery day following.

Lorna and her family obviously loved Penny dearly, and I counted myself lucky to have been able to have such a kind and loving family take over care for Penny for the balance of her life.

I was in touch with Lorna over the holidays this year, and found that Penny had died last February 3. Lorna apologized for not telling me at the time… “I guess I didn’t know how” was what she wrote yesterday. I know exactly what she meant.

On our way to El Paso, in the summer of 1990, we stopped at a roadside rest stop for a picnic. I had my guitar with me, and brought it out to haggle out some tunes before we headed off. I wrote a little song called “Penny, Super-Dog of the Azores” in that rest step, which Stefan sang for several years after. I still have the tune running through my head.

When you don’t have a dog, it’s easy to get cynical when people start writing about their powerful relationships with their animals. I’m prone to this myself. And yet as I write this, 16 years after picking Penny up from the pound, my throat is clogged and there are tears in my eyes.

So, good-bye to you, Super-Dog. Be well, and keep those other heaven-dogs in check.

If you buy the National Post from the newsbox in from of The Guardian on Prince Street, it will cost you $1.00. If you step inside and buy it from the front desk, it will cost you only 75 cents.

If you want to withdraw money from a “foreign” ATM in downtown Charlottetown, the National Bank will only charge you a $1.25 fee, whereas the TD will charge $1.50. [Thanks to Dan James for this pointer]

If you wear an additional pair of socks and a tight-fitting pair of slippers, your feet, and thus your entire body, will feel much warmer, and you needn’t have the heat on as high in your frigid house.

There’s some freaky shit going on regarding wind, hydrogen, and Prince Edward Island energy policy. So freaky that it’s hard to believe. For example, here’s Hon. Jamie Ballem, Minister of Environment and Energy, quoted in a CBC story:

“It’s such a renewable, and it’s so clean,” says Ballem. It’s our oil. It’s our opportunity because it’s one thing we do have here. We have good wind conditions. Maybe we should be maximizing it. If we can get Maritime cooperation then it makes it a lot easier for us to look at. Instead of 15 per cent of our energy coming from wind, can we make it 50 per cent, can we make it 100 per cent?”

I had to read that paragraph three times before I believed it. Some days, it’s just good to be alive.

Thanks for Rus, a helpful reader, I have news of Hermann Kleefisch, the Islander who is driving around the world. Rus points to this story from Chiang Mai which provides an update on Hermann’s progress to date. To summarize: he’s made it as far as Thailand, although without, alas, his VW Microbus, which was sent back to Germany without him at the Vietnamese border. Hermann is continuing by foot, train and bus.

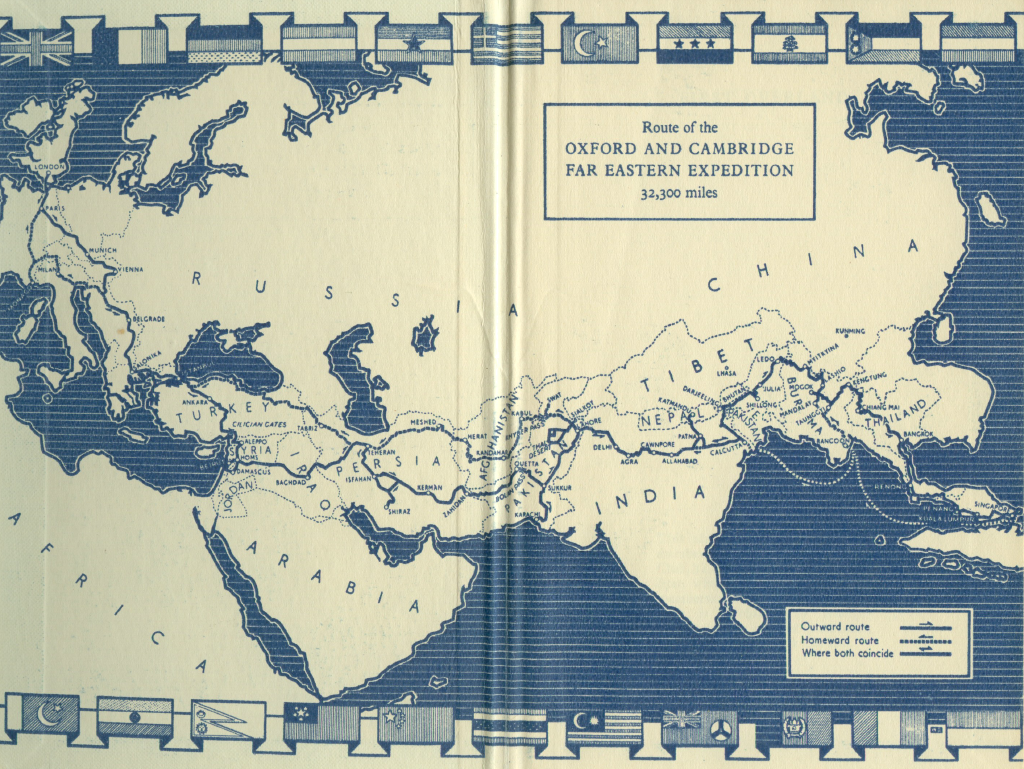

In the mid-1950s, in a student residence at Cambridge University in England, the Oxford and Cambridge Far East Expedition was born:

It began, like almost everything else at Cambridge, late at night over gas-ring coffee. I lived on the same college staircase as Adrian Cowell, and I had gone up to his room one winter evening for a nightcap. He started talking of an idea he had for a combined Oxford and Cambridge overland expedition to Singapore.

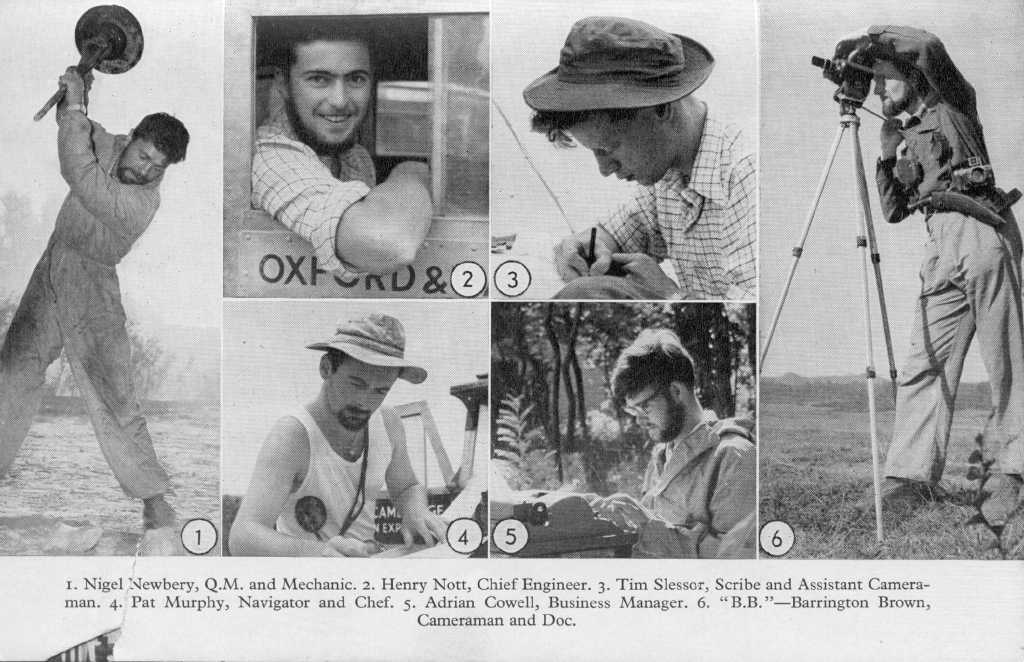

Six men, one from Oxford and five from Cambridge, set off from London in a convoy of two Land Rovers, to drive to continuously overland to Singapore. The book First Overland, written by Tim Slessor, one of the team, is the tale of their voyage.

Largely because of the nature of the expedition team members, the book is chock full of interesting technical information: we learn how the Land Rovers were packed, what that carried, and how they performed. There’s information about food on the road, camping on the road, and relations among the team members on the road.

While Offbeat in Asia concerns expedition by a team of two, and In the Circle of the Sun by a rollicking family, this book is very definitely about a bunch of wise-cracking sophomoric graduate students. They’re smart, witty, ingenious, and not a little pretentious. If my landlords at silverorange decided to travel around the world together, I imagine the tale would be similar. While this might not be every reader’s cup of tea, it was mine, and I flew quickly through the book over a couple of nights.

The writing is as you might expect from such a group (Slessor is primary author, but there are diary excerpts from others, and several other team members take on chapter):

Up at six and off by seven. Stacks on the agenda to-day. The usual fried eggies and buffalo butter for breakfast. Mustafa, the driver of the jeep, wants a chit signed to testify to his mechanical ability Authority delgated to Henry, who writes, “Mustafa is a bloody marvellous mechanic, signed Chief Engineer Oxcam Far Eastern.”

The expedition set off from London and headed south-east through Vienna, Belgrade, and Salonika, then east through Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Burma and then south-east through Thailand to Malaysia and finally to Singapore.

Perhaps the most compelling section of the journey is that which took the expedition along the Stillwell Road, a road constructed for World War II that had been unused, and assumed impassable, since the end of the war. Using a combination of connections, guile, tenacity and copious use of the winch, both Land Rovers made it down the Stillwell Road. What’s more, they did so in a rather miraculous three days:

On looking back, the first hundred miles of the Stillwell Road was much easier than we had ever expected. Anticipating very difficult conditions, we had armed ourselves with everything from three weeks’ food supply, to water-sterilizing tablets, from winches to machetes. A part of our success so far was due to luck — the monsoon had been unusually light, and therefore the rivers and hills were not as sodden as they might have been, neither were there any big landslides to block our way. But undoubtedly another part was due to the preparations we had made, and without eight forward gears, four-wheel drive, and winches our overland venture might had have unstuck a dozen times in the first twenty-four hours from Ledo.

While the book relates the tale of the overland drive from London to Singapore, in fact the expedition continued with a drive back the other direction (albeit steaming from Singapore to Calcutta over sea). Slessor explains: “I have decided to leave them out… because, although on reaching our outward destination we had to turn round and come back, it occurs to me that it is expecting too much of the reader to do likewise.”

The book closes with a series of appendices covering medical, mechanical, navigation, photographic, quartermastering, cookery and money issues. There are well-drawn maps throughout, and several sections of photographs.

First Overland was a lent to me by my friend Daniel, in December of 2002, temporarily purloined from his parents’ library. It is out of print, but used copies are abebooks.com.

I am

I am