My friend Carol turned me on to the fact that Pet Valu, in the Smitty’s Plaza in Charlottetown, has a do-it-yourself dog washing station.

For $10, you get access to a tub (at chest height), shampoo, towels, a dryer, grooming tools and treats.

There’s no time limit. What a great alternative to washing Ethan at home in the bathtub!

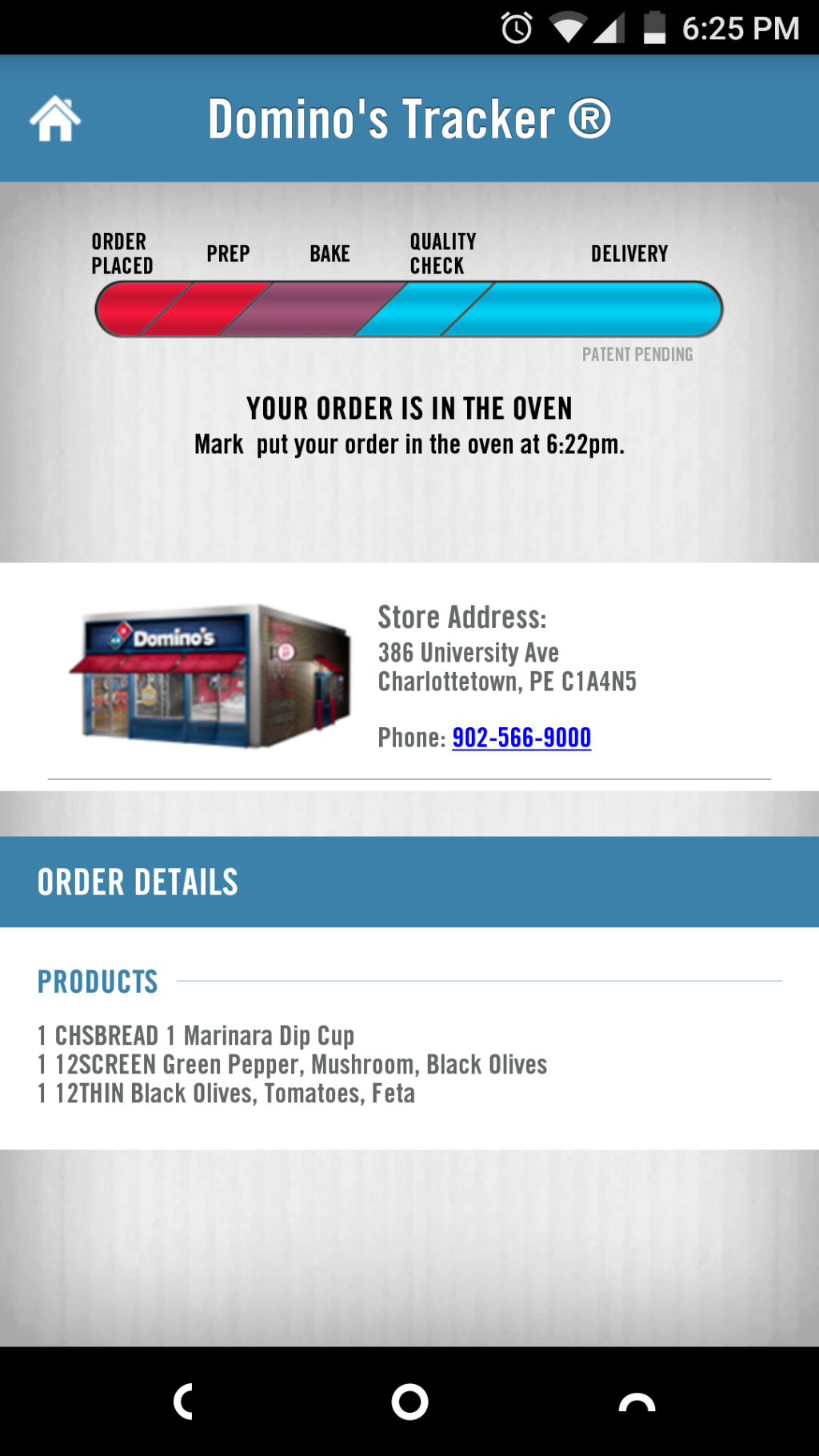

I have no idea whether Domino’s has the best pizza in town — I’m pretty sure it doesn’t — but there’s no doubting it has the best mobile app. And that wins me over 9 times out of 10.

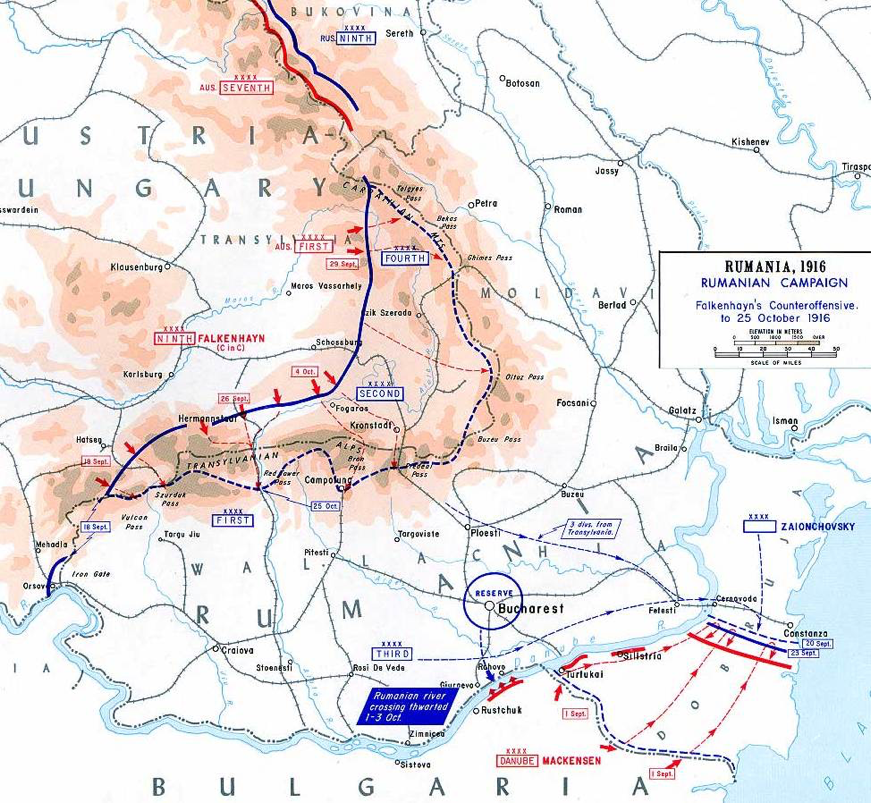

If you are reading the headlines of The Guardian newspaper 100 years on, you’re now making your way through the fall of 1916, and no more than a day or two passes without an update from the front in Roumania. Here are the headlines on those stories, working backward from November 3, 1916 to October 3, 1916.

Wikipedia has a good review of Romania’s role in World War I, including this illustration of the borders and campaigns of this front:

With the end of October comes the opening of Victoria Row in downtown Charlottetown — the spine that connects my house to my office — to vehicles for the winter. Summer truly is over.

A few days ago, I mused aloud, both here and on Twitter, “Why do interview subjects say ‘that’s a great question’? I’ve never said that, and never understood it.”

I seems this was an unwitting lie; witness this interview I did just over a month ago with Global News in Halifax about the new edition of The Old Farmer’s Almanac:

To quote from the offending clip:

Interviewer: And you said as well that you’re from PEI, so you’re quite familiar with weather patterns and the way things kind of pan out here in Atlantic Canada with lots of snowfall. I know precipitation-wise, averagely, how much do we typically see here for snowfall?

Me: That’s a good question. I would say “a lot,” which reflects how much I know about the detail of the weather.

That’s a pretty good illustration of what Piya Chattopadhya described as “their brain is telling them to buy time cuz they don’t know what to say.”

I truly had no idea how much snow Prince Edward Island receives in the winter, and I truly did need that few seconds to come up with the best answer I could, which was “a lot.”

Et tu, self?

Barry Hicken served as Prince Edward Island’s Minister of Environmental Resources in the Catherine Callbeck Liberal government in the mid-1990s, a time when I was working with the province on the first iteration of its website.

Barry was well-regarded in this role, and well known, at least inside the provincial public service, for signing things with a green pen.

I don’t know why this fact about him stuck with me, but it did, and I’ve told the story of “Barry Hicken and his green pen” many times in the years since (I’m the kind of person who has conversations about things like ink and pens, where these things come up more than might be typical).

This morning I was sitting across from a friend in Casa Mia in downtown Charlottetown, and who should come in the door and sit at the next table over, but the selfsame Barry Hicken.

I couldn’t help but bring up the green pen, especially as I myself carry a green pen everywhere I go, one I purchased at MUJI in May in Berlin:

Barry smiled , reached into his pocket, and pulled out his own green pen. Some habits never die.

He then related how his write-in-green-pen system started: when he became Minister, he asked everyone in the office if they had a green pen. When the universal answer was “no,” he replied, “okay, nobody start” and then set down the rule that only he was to use a green pen. As a result, everyone in the department knew that when they saw something in green pen, it had come from the Minister.

Brilliant.

This morning on Twitter I asked “Why do interview subjects say ‘that’s a great question’? I’ve never said that, and never understood it.”

The question brought some interesting responses from journalists themselves, the questioners-being-praised (I’ve corrected some spelling errors to protect the innocent):

Dave Atkinson, freelance journalist:

gives you about seven seconds to think of a real answer. It’s more verbal punctuation than anything.

there are also a bunch of conventions in “tape/talks”, that don’t exist in real conversations. “Well, host-name, blah blah blah…”

I’ve also heard it used in a “oh god, I’ve been asked this so many times” kind of way.

Piya Chattopadhya, CBC Radio and TV Ontario host:

generally their brain is telling them to buy time cuz they don’t know what to say

Steve Rukavina, CBC Montreal reporter (and my brother):

it’s usually a pretty clear signal to me when I’m interviewing that they have no intention of actually answering the question

Kerry Campbell, CBC Prince Edward Island reporter:

I think politicians & bureaucrats told to do that as part of media training. Trying to butter up interviewers? Sound conciliatory?

I remember when the training started to include “say the interviewer’s name as often as possible.” I could live without that

Jessica Doria-Brown, video journalist for CBC Prince Edward Island:

They say it because they think it will butter you up. Instead, it often comes off as condescending and smarmy.

Taken in sum, there’s pretty clear guidance for we-the-potentially-interviewed to simply stop doing this.

You have been warned.

One of the most helpful services offered by our provincial government here in Prince Edward Island has always been Island Information Service.

By calling the easy-to-remember 902-368-4000 telephone number, I can talk to a friendly, helpful, knowledgeable information specialist who can help me navigate the complex thicket of the bureaucracy.

Except that now I can’t.

When I call that number now, rather than a friendly voice on the other end, a robot answers the phone and asks me to navigate a telephone tree: “for tax questions, such as property tax, deed registry, HST and pensions, press 2,” and so on.

Setting aside the wicking away of the helpful personal service, this approach is fine if your query happens to fall into one of the 5 options offered. But citizen questions are often more complicated than that, and it’s difficult to tell which bureaucratic box to tick. Talking one-on-one with Michelle or one of her colleagues would always result in an answer; tapping to the robot can quickly get frustrating.

But even setting that aside, robots don’t always work like they’re supposed to. Humans sometimes don’t work too, but with robots it’s often a binary breakdown — they work, or they don’t — rather than the “I’m having a bad day and aren’t as pleasant as I usually am” way that humans tend to degrade.

This was my issue today: I phoned Island Information Service to get information about how to get a voluntary ID for [[Oliver]]. I dutifully pressed 4 and then 2, and the robot told me I was being “transferred to Access PEI.”

A pause. And then “the number you have dialed is not in service; please check the number and try your call again.”

Oh no.

Systems are fallible — I’ve made a career out of managing their fallibility, so I know this perhaps better than most. But because I can only talk to a robot, I can’t report the issue: pressing 0 to speak to an operator doesn’t work. There’s no “to report an issue with this system” option. There are no search results on the government telephone directory for “Island Information Service.”

And so I’m stuck.

And thus I pen this bug report here, with hopes that the robot will read it and take corrective action.

And maybe bring Michelle back?

Eastern Graphic publisher Paul MacNeill’s column this week is a well-worded call for humility and humanity in journalism and politics both. Paul writes, in part:

Weekly I have the luxury of picking a topic and, more often than not, railing against some government action or lack thereof. When compared to e-gaming or PNP it is obvious not all controversies or scandals are created equal. This space has been far ahead of the curve in arguing for strong measures to deal with our fiscal issues and capacity, educational excellence, regional cooperation, size and focus of government and rural integrity and the demographic challenge we face.

Could some of the arguments be more nuanced or subtle? For sure. But many, if not all of these issues, enjoy a higher level of public awareness in small part because of these ramblings.

Fifty years ago former Island Premier Alex Campbell said in an address focussed on regional cooperation that “such complex concepts as these are very easily simplified, and even more easily promoted; but they are awfully difficult to translate into specific forms of co-ordinated action.”

Those words hold true today. Complex topics can be dramatically simplified in 600 words. PEI is still a leader in promoting regional cooperation. Wade MacLauchlan is doing everything he can to move the file forward, but winning change has as much to do with the willingness of your dance partner as anything else. If Nova Scotia or New Brunswick don’t want to dance, maybe it’s time we look for another partner.

I appreciate, particularly, the invocation of Alex Campbell’s advice, advice that essentially boils down to “ideas are easy, implementation is hard.”

One of the things I encounter frequently in my work in the non-profit world, is the lack of recognition of this fact: there is a common belief that if something is “right,” it should be implemented, and that any barriers to its implementation are barriers introduced by people who simply cannot see the “rightness,” or, worse still, are actively supporting things that are “wrong.”

No more so is this true than in public education: I’ve had scores of one-on-one conversations with teachers, principals, public servants and politicians and, almost universally so, their take on public education is significantly more progressive and enlightened than the education system we have on the ground would suggest. It is not for lack of ideas or inspiration that this is the case: it is because the public education system is a complex system, and we’re not very good, collectively, at changing complex systems. Systems thinking is a rare skill; there are not many who can see the forest for the trees, and even fewer who have any skill at convincing others that there is, in fact, a forest.

At this week’s meeting of the Learning Partners Advisory Council one of the members used the metaphor of “steering the ship” by way of suggesting one way of characterizing the council’s role in learning in Prince Edward Island. I suggested, as an alternative, that we regard learning as a flotilla not a single ship, and that our influence could, at best, be seen as an ability to nudge, not steer.

I think that’s what Alex Campbell was saying, in a different way, 50 years ago, and what Paul MacNeill ruminated on this week: in the grander scheme of things, being convinced of the rightness of your cause is insignificant compared to the challenges of understanding the point of view of those who disagree with you, and understanding the interplay between the components of the system you hope to change.

I am

I am