In Anatomy of an Indian Address, Gowri N Kishore takes a deep dive into how civic addressing works in India:

India has no standardised way of describing addresses as Western countries do. And a one-size-fits-all approach may not even work here because different states have their own terms like street, main/cross, colony, and more. Each address is its own little adventure. Phew!

One of the under-appreciated public works megaprojects here on Prince Edward Island is the civic addressing system: introduced in the early 2000s, the system was designed to enable the introduction of 911 emergency service in a province that, outside of larger cities and towns, had no standardized address system. From the original Civic Address Standards and Guidelines:

The civic address standards outlined ensure that all residences on Prince Edward Island are universally and uniquely civic addressed. The civic address guidelines present recommended rules to follow when providing new civic addresses. The document also describes situations where undesirable (unacceptable) civic addressing may exist and recommends possible remedies.

…

The present status of civic addressing within Prince Edward Island can be summarized as follows:

- Both Charlottetown and Summerside are essentially complete;

- Five of seven towns are essentially complete;

- Three of fifteen communities with official plans are essentially complete;

- All other areas within PEI are minimally or non civic addressed.

I was under contract to the Province of PEI throughout this process, and was privileged to witness, up close, what a Herculean task it was to find a unique civic address for every property on the Island: not only did addresses themselves need to be assigned, but road names needed to be established (and made unique within a county), and, in many cases, new “civic address communities” established, as much of the province isn’t covered by formal municipalities.

The civic address system was one of the signature achievements of former Provincial Tax Commissioner Jim Ramsay: while the process involved many people across departments and agencies, inside government and out, it was Jim who was the driving force. And that the data underlying the system — a geolocated civic address database — was made freely available to the public is a testament to Jim’s ability to see the tremendous upsides of such a move (I was in the room when the decision to do this was made, and the page offering the data was online the same day — there was no way I was going to miss the opportunity to see such a resource be made public, and wan’t to ensure the horses were out of the barn before any layer of the bureaucracy changed its mind).

This summer Lisa and I are performing, with our improv troupe No Questions, every Wednesday night in August at the Benevolent Irish Society at 7:00 p.m. (admission by donation; bar opens at 6:30 p.m.).

The troupe is an outgrowth of Laurie Murphy’s improv classes, classes I started in November of 2021, and that Lisa, who’s had her toe in and out of improv for many years, joined this winter.

As I’ve written about before, it’s not a word of a lie to say that performing improv has changed my life. The devil may care “yes, and” attitude it has steeped me in was the pathway I needed to find my way through the forest to Lisa. It’s the juice that’s powering an upcoming career turnabout. My mind has been opened I’m a better listener, a better risk-taker. I’ve become convinced that it’s a curative experience that everyone—especially the shy, retiring, quietly wry, not-jokey types who would never every consider it—should try at least once.

We segued from improv training to troupe rehearsal in July. Last week was our final rehearsal before opening night last night.

And it was shit.

We were off the rails: not listening, not connecting, forgetting how to say yes, ignoring the fundamentals. We micromanaged ourselves into a malaise.

We came home dispirited. I thought idly whether there might be a way to get out of the August performances. For the first time since I started, I wasn’t excited about performing.

Sigh.

But we pushed on. Rallied.

I agreed to host the opening night. Lisa agreed to host the “PEI Famous Celebrity Interview” that anchors the second act. We made a conscious effort to show up last night.

And, as it turned out, so did the rest of the troupe.

What, just a week before, had felt like an irredeemable train wreck, last night just gelled.

We listened. We made each other look good. We had fun. And we finished the night with the unmistakable high that being vulnerable with a group produces.

So whereas two days ago I was loathe to even admit that we’re performing this August, now I want everyone I know to come. I’m proud of our merry band, I’ve seen what we’re capable of together, and I know in my heart that we’re going to get better every week we perform.

Again, the details:

- Every Wednesday in August (August 9, 16, 23 and 30, 2023).

- Benevolent Irish Society Hall, 582 North River Road, Charlottetown.

- Bar opens at 6:30 p.m., show starts at 7:00 p.m. and runs to 9:00 p.m.

- Admission by donation.

- Add the shows to your calendar with this ICS file.

Please join us. Tell your friends. Bring your friends.

Currently posted up at LOLI in Moncton, stopping in for an espresso and a pause before heading back to the Island after dropping family off at the train.

Coffee is good. Vibe is relaxed. Wifi is fast. I believe that fellow on the balcony is a DJ.

Not quite Berlin.

But certainly not the Moncton I arrived in for the first time—at the selfsame train station—40 years ago this summer.

Olle and Luisa were out wandering this morning, and came across a building in industrial Malmö with this luscious lettering:

I love so much about that typeface: the low crossbars (A, E, R, K), the subtle tuck-in of the umlaut on the O, the dreamy swoopiness of it all (see also Wouter on the death of swoopiness).

Of course I had to do some detective work and find the sign in context.

Fortunately Olle had left the geolocation embedded in the JPEG’s EXIF, and I was able to find it with a little Google Maps wandering; it looks like a power substation:

A search for more information about Malmö Elverk led me to this collection of images in the collection of the Malmö Museum, one of which jumped out at me:

It’s a similar building, presumably also a substation, and also with lovely typography. The museum’s digital collection helpfully contained a street address in the item’s metadata, and so with some additional Google Maps wandering, I was able to see this location in its current context on Erikstorpsgatan:

One of the under-explored aspects of Google Street View is that archival images, stretching back more than 10 years now, are browsable. Meaning it’s possible to see a visual history of the graffiti on the Erikstorpsgatan substation from 2019 to the near-present.

Here’s June 2009:

Two years later, in September 2011, there is some of the 2009 work still there on the grey door, but the brickwork seems to have been cleaned and re-tagged:

Three years after that, in June 2014, there’s been an attempt, by someone, to reset things with grey and purple:

Five years later, in August 2019, the building has been completely refreshed, including the signage on the grey doors, and some landscaping:

In October 2021 things are much the same:

But by June 2022, the most recent photo in Street View, there are new tags:

Apple’s Street View equivalent has an even clearer view from June 2022:

I am fascinated by the world of letters, and one of the things I love most about wandering about the world, when I’m able, is paying attentions to signs, noticeboards, warnings, posters. It’s nice to be reminded that when I’m close to home, I can still venture out on the screen. Thank you to my wandering friends for that.

Back in 2001 I related my history of auto insurance, a path that led me, on Prince Edward Island, first to Gordon Full, a small office, staffed by two people, that was responsive and friendly beyond all belief.

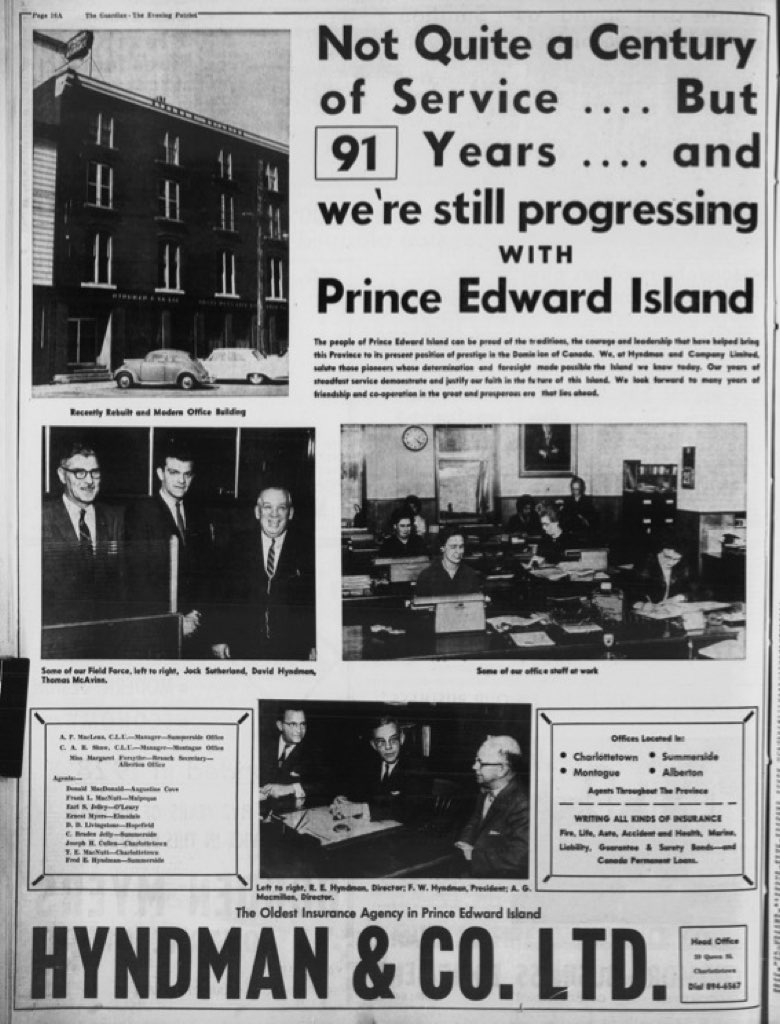

Gordon Full eventually sold out to the still-local-but-not-as-small Hyndman and Company, and I’ve been happy to have Hyndman’s as my broker for the 22 years since.

Hyndman and Company was one of the Island’s oldest companies of any sort; many years ago I ask the Public Archives for information they might have in their records about the company’s telephone number, and the ever-helpful John Boylan replied:

The 1894 telephone directory lists FW Hyndman Insurance as being No. 67, 2 Rings. Customers had individual numbers ranging from one to three digits. Number one was the Rev. G.M. Campbell’s residence. The Falconwood Asylum was number fifteen.

Although other phone lines were added to Hyndman Insurance, 67 remained the private office number for the business up to 1952. By 1952 customers had a mix of two, three and four digit telephone numbers.

There’s a gap in our telephone directories from 1952 to 1959, but by ‘59 Hyndman Insurance was a four digit number, 6567. All numbers in the Charlottetown exchange appear to have been four digit ones by this year. By 1961 Hyndman Insurance was 894-6567.

I was proud to be associated with a company with a long history, a local company that was just a few blocks or a quick phone call away.

Alas, if you dial that telephone number today, you get a message that it’s no longer in service. A metaphor for the company itself: Hyndman’s has changed a lot in recent years and I’ve become increasingly less satisfied with the service I’ve been getting: the agent I’m assigned to keeps changing, and getting in touch has become increasingly cat-and-mouse. Ten years ago my insurance company, Dominion of Canada, was swallowed up by the US-based Travelers Insurance, adding an additional layer of complexity when it came to yearly renewal. The straw that’s in the process of breaking the camel’s back is that Hyndman and Company was sold to Westland Insurance Group this year, “one of Canada’s largest independently owned insurance distribution businesses.”

So, now that any trace of dealing with a local company has been removed, any need to avoid shopping widely and broadly in the auto insurance marketplace has also been removed, and I’m open to any suggestions you might have: I’m shopping for price and for convenience. If I don’t ever need to talk to a person, that’s a bonus. Which is quite a journey from sitting down across from Gordon Full 30 years ago. But such is the modern world of commerce.

I was sad to read yesterday of the death of Jim MacAulay.

The public service contributions of the MacAulay family to are legion, and I crossed paths with each of the MacAulay brothers over the years.

Jim had a special place in my heart: as a lifelong educator he contributed enormously to public education on PEI, and I had the pleasure of sitting around the luncheon table with him at the PEI Retired Teachers Association; he was funny, curious, and willing to tell tales.

Among Jim’s many contributions to the province, his 1996 Eastern School District Facilities Review was one of the most significant: it’s a 433 page deeply detailed review of the school infrastructure in half of the Island that begins with a section “How Things Came to Be”:

In a study of this nature, a historical review provides useful perspective. Until the late 1950’s and early 1960’s education in Prince Edward Island was primarily provided by small, one-room, community schools. Frequently a farmer provided in a comer of one of his fields, sufficient space for the school building and its playground. Each of these structures and its administration was an entity unto itself. In many of our communities, this model served very well for the social, economic, technological and demographical climate of the day. Many very prominent citizens emerged from these institutions.

The report is at once a detailed review of school buildings (Parkdale Elementary: “Two new furnaces were installed in the last 3 years.”), and a capsule history of public education on PEI (“If one investigates school size over the past fifty years, many school sizes put forth as ideal. At one time people felt that very large schools were the answers. Before long problems which surfaced led to a change of thinking and understanding that schools could be too large to manage.”).

It is comprehensive, well written, and its publication served as an inflection point in how we think about school infrastructure, coming 30 years after the big push to school consolidation and construction that happened in the 1960s.

For anyone wants to understand “How Things Came to Be” from a 2023 perspective, it’s the place to start reading.

Jim MacAulay will be missed.

A photo of me, at improv class, taken by Laurie Murphy. My mother has taken to telling me that I seem preternaturally tall of late; until now, I’ve never seen it.

Tamar Adler, in An Everlasting Meal: Cooking with Economy and Grace, on poached eggs:

I’ve heard of a lot of perfect ways to poach an egg, I’m sure they work. The problem with them is that to poach eggs is to understand egg cooking as you can’t when you cook them any other way.

A boiled egg stays secret until it’s cooked, and a frying egg sizzles in fat, too hot to touch. But poached eggs are cracked out of their shells and cooked directly in barely simmering liquid, which means you can literally feel them as they cook. The trouble with setting a timer, covering a pan, and walking away is that you end up bound to your trick, lost without a timer, stuck without a lid.

I followed her advice and made—though did not eat, given my eccentricities—poached eggs this morning for the first time.

(Photo by Lisa)

I am

I am