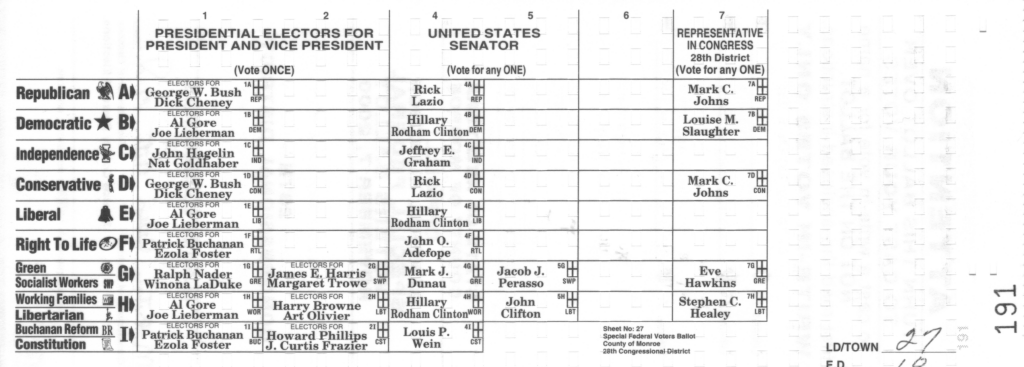

Here’s what my U.S. election ballot looked like:

See the little “crosses” beside each candidate’s name? Well, to vote I had to take my “paper-clip like device” (their words, not mine) and poke out a “chad” on the card. It’s these chads that are now the subject of controversy in Florida. The latest I’ve heard is that in Palm Beach County there have to be at least two corners of a chad detached for the vote to count.

Weird coincidences: I was once in Palm Beach County on a mission to see the Disney Store there. It was a lot like Scarborough, but warmer. Robert Kahal, Irving Kahal’s brother, lives in Palm Beach County. Hmmmm.

So it’s 10:00 p.m. on a Saturday night and I want to sent a small package to New York City by regular postal mail. There is a Canada Post mailbox two blocks from my house. But I need a CN 22 (see story below) because my package qualifies as a “small packet.” I go to the Canada Post website, naively thinking that I will find one to download there. Nope. Same thing at the U.S. Postal Service site. So I get in the car an drive up to the “let’s decentralize the Post Office and put little Post Offices in places like variety stores, and they’ll be more convenient because they’re open all the time” Quik Mart, which is about 15 blocks away.

![]() “The Post Office is closed. It will be open on Monday,” says the snarky clerk.

“The Post Office is closed. It will be open on Monday,” says the snarky clerk.

![]() So I drive up the road further to the IGA grocery store. I arrive at 9:59 p.m. They have just locked their doors.

So I drive up the road further to the IGA grocery store. I arrive at 9:59 p.m. They have just locked their doors.

![]() So I drive way out to North River, on the outskirts of the city, to the PetroCan with Postal Outlet I used to frequent when we lived out that way.

So I drive way out to North River, on the outskirts of the city, to the PetroCan with Postal Outlet I used to frequent when we lived out that way.

![]() “Sorry, we’re not a Postal Outlet anymore; you’ll have to go into Cornwall… but they’re not open until Monday,” says the nice clerk.

“Sorry, we’re not a Postal Outlet anymore; you’ll have to go into Cornwall… but they’re not open until Monday,” says the nice clerk.

![]() So I come home.

So I come home.

![]() Finally, I find a sample CN 22 form on a BC Government website, and print it out, and stick it on.

Finally, I find a sample CN 22 form on a BC Government website, and print it out, and stick it on.

![]() Now I’m going to walk the two blocks to the mail box.

Now I’m going to walk the two blocks to the mail box.

Form CN 22, Customs declaration (pictured here) is an international form used to declare the value of international mail shipments. It is mandated to be green in colour. There is now a proposal afoot to allow it to be white, so that it can be produced by personal computers without green paper. Wouldn’t it be interesting to be at the meeting of the UPU where this will be considered?

Form CN 22, Customs declaration (pictured here) is an international form used to declare the value of international mail shipments. It is mandated to be green in colour. There is now a proposal afoot to allow it to be white, so that it can be produced by personal computers without green paper. Wouldn’t it be interesting to be at the meeting of the UPU where this will be considered?

From my eagle-eyed brother Mike: Seen on sign of child picketing with parents at Waterdown school over Ontario teachers’ strike: “We need are teachers back.”

As regular readers might have imagined, my recent I’ll Be Seeing You obsession will made the jump to radio on Friday. You can listen in RealAudio right now if you’re so-equipped.

From my brother Johnny:

In the telecommunications game, distinctive and compelling are far less important adjectives than shiny and modern looking..I disagree: the only thing that Island Tel has going for it is its root in Prince Edward Island, and the strong connection of Islanders to this notion.

Old Identity |

New Identity |

I happened upon a rare Island Tel truck sporting their old visual identity (brown, white and orange, with a classic logo incorporating a old-style dial telephone). Seconds later, I passed a truck sporting their new identity (white, orange and green, with generic spinning globe logo). Why don’t they realize that their old identity was much more distinctive and compelling than their new one?

Many say that the Internet has led to the death of letter writing. This isn’t true of course: letter writing now simply happens online. However what is true, in my experience, is that the Internet has led to the death of sending cookies and squares in the mail. It must be 10 years since I sent or received cookies or squares. The last thing I remember was sending 15 pounds of gooseberries from Montreal to Toronto in about 1989. Then emptiness. Something must be done.

Irving Kahal was born in 1903 in Houtzdale, Pennsylvania and died in 1942 in New York City at the age of 39. As a lyricist, he collaborated with Sammy Fain for 17 of those years, producing songs like Wedding Bells Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine and Let a Smile Be Your Umbrella. Their most well-known song is I’ll Be Seeing You, released in 1938 and a hit in the 1943 film of the same name.

![]() Among those who have recorded I’ll be Seeing You are Vera Lynn, Holly Cole, Tony Bennett, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Mandy Patinkin, Jimmy Durante, Iggy Pop, Billie Holiday, Rickie Lee Jones, Liberace, Barry Manilow and many others. The most compelling version I’ve come across is by Neil Sedaka.

Among those who have recorded I’ll be Seeing You are Vera Lynn, Holly Cole, Tony Bennett, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Mandy Patinkin, Jimmy Durante, Iggy Pop, Billie Holiday, Rickie Lee Jones, Liberace, Barry Manilow and many others. The most compelling version I’ve come across is by Neil Sedaka.

![]() The 1943 movie I’ll Be Seeing You starred Ginger Rogers, Joseph Cotten and Shirley Temple. The song in the picture was sung by the off-screen voice of Louanne Hogan.

The 1943 movie I’ll Be Seeing You starred Ginger Rogers, Joseph Cotten and Shirley Temple. The song in the picture was sung by the off-screen voice of Louanne Hogan.

Today I was making reservations on the Air Canada website from Charlottetown to Toronto. I was quoted a fare of $723 for two people return, which was an excellent fare, and so I proceeded. Then I got an error from the website, asking me to press the BACK button in my browser and click Accept again. When I did this, the fare had doubled in price. I phoned technical support at Air Canada, and their response to my question about why this had happened was, in essence, that’s not my department. When I asked who I could talk to, the response was there’s nobody you can talk to about that problem. Sigh.

I am

I am