Last week I read an interview with Musician Tashi Wada in The Creative Independent. The interviewer, Grayson Haver Currin, asked Wada about his parents:

At what point did you realize that everyone else’s parents weren’t artists, or that something was different with your family?

We lived in one of these Fluxus co-op buildings, so it was a lot of Fluxus artists. Simone Forti was our nextdoor neighbor. Nam June Paik lived upstairs. At school, since it was New York, it was a pretty eclectic mix of people. But the specific memory I have was we were asked to go around the class and say what our parents did. My dad did all kinds of plumbing in these buildings in SoHo, but I kind of knew that wasn’t really what he did. It was a side of his life, but it was not how he identified as a person. I didn’t really have a good answer in class. I remember going home and asking my mom, “What does Dad do?” She said, “Well, just say he’s self-employed.” Somehow that made sense. It makes sense to me now, as an adult—I’ve chosen a life that is determining it day-to-day, month-to-month. It feels self-directed.

I’d never heard of “Fluxus co-op buildings” nor of “Fluxus artists” and this led me down a fascinating rabbit hole; what emerged was a portrait of a movement that I could get behind:

Fluxus had no single unifying style. Artists used a range of media and processes adopting a ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude to creative activity, often staging random performances and using whatever materials were at hand to make art. Seeing themselves as an alternative to academic art and music, Fluxus was a democratic form of creativity open to anyone. Collaborations were encouraged between artists and across artforms, and also with the audience or spectator. It valued simplicity and anti-commercialism, with chance and accident playing a big part in the creation of works, and humour also being an important element.

The rabbit hole exited at Robert Filliou and La Cédille qui Sourit, a shop in Villefranche-sur-mer, France, that art historian Natilee Harren introduces, in La cedille qui ne finit pas: Robert Filliou, George Brecht, and Fluxus in Villefranche:

In the summer of 1965, Fluxus artists George Brecht and Robert Filliou opened a back‐alley shop in the French Riviera town of Villefranche‐sur‐Mer called La Cédille Qui Sourit, or “The cedilla that smiles.” The Cédille sold unique objects produced there by the artists as well as books and editions from Fluxus, MAT Editions, Something Else Press, and others. Yet this “non‐shop” (as Filliou called it), which looked more like an atelier than a store, was never commercially registered, and opened only by appointment. The experiment failed within three years. This essay sees the Cédille as a momentary flowering of the model of Fluxus’s “artworks‐in‐flux” into an alternative, anti‐instrumental, artist‐run economy of production, distribution, and exchange, developed in response to the expanding capitalization and exploitation of art and artists in the 1960s. Aspects of the Cédille discussed in this context include ephemera, writings, and objects such as the suspense poems, the “Non‐School” of Villefranche, the café‐genius, the gifting project, and the cedilla grapheme itself. Finally, Brecht and Filliou’s activities at the Cédille are considered alongside Hannah Arendt’s writings on labor, work, and action, especially in regard to the latter’s relationship to politics, art, and culture.

Also something I could get behind.

The works associated with Filliou, Brecht, and La Cédille qui Sourit are compelling.

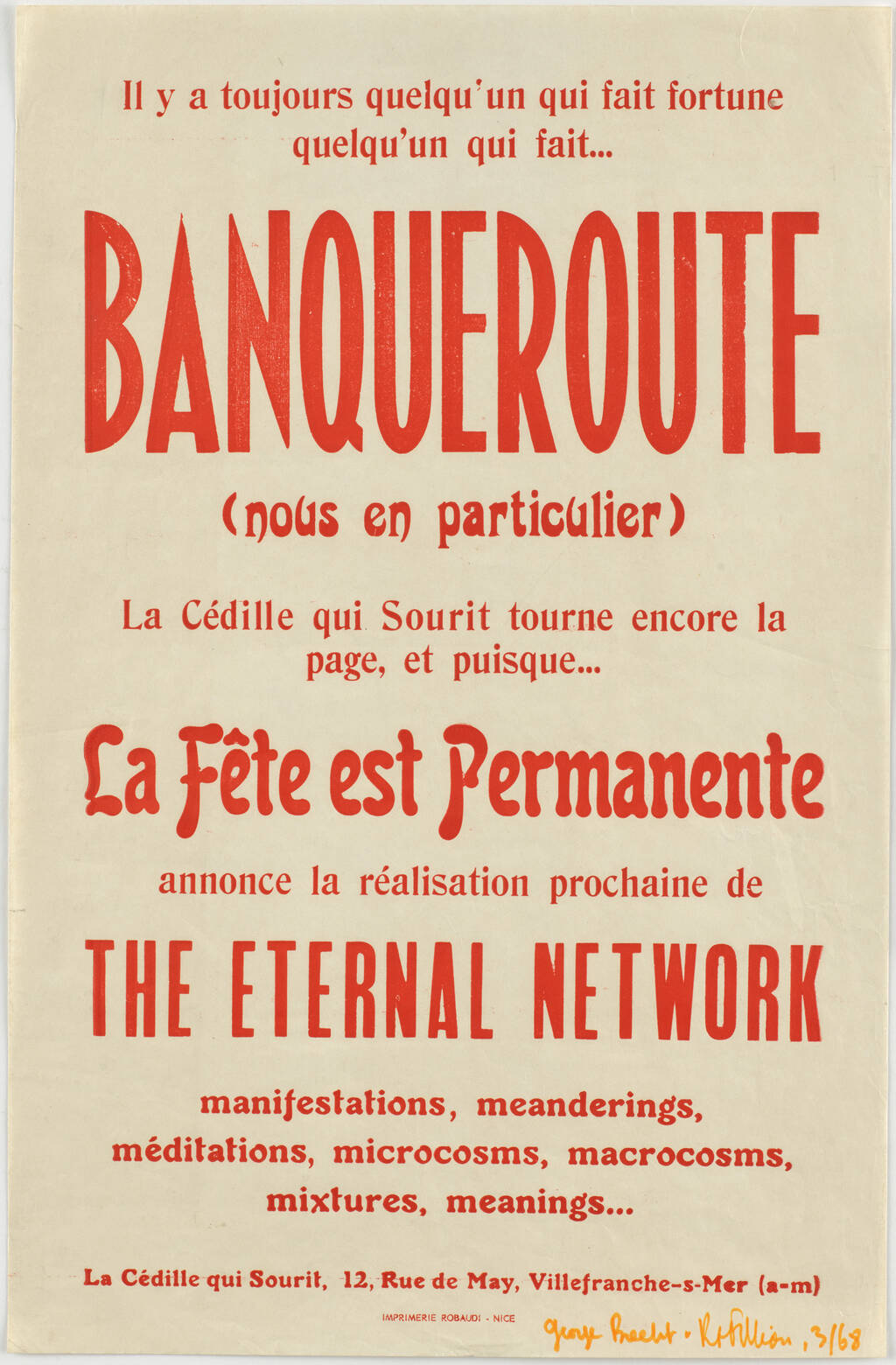

This poster, from MOMA’s collection, for example, starts “there is always someone who makes a fortune, someone who is bankrupt (us in particular)”:

Or A New Way to Give People Headaches, also from MOMA’s collection:

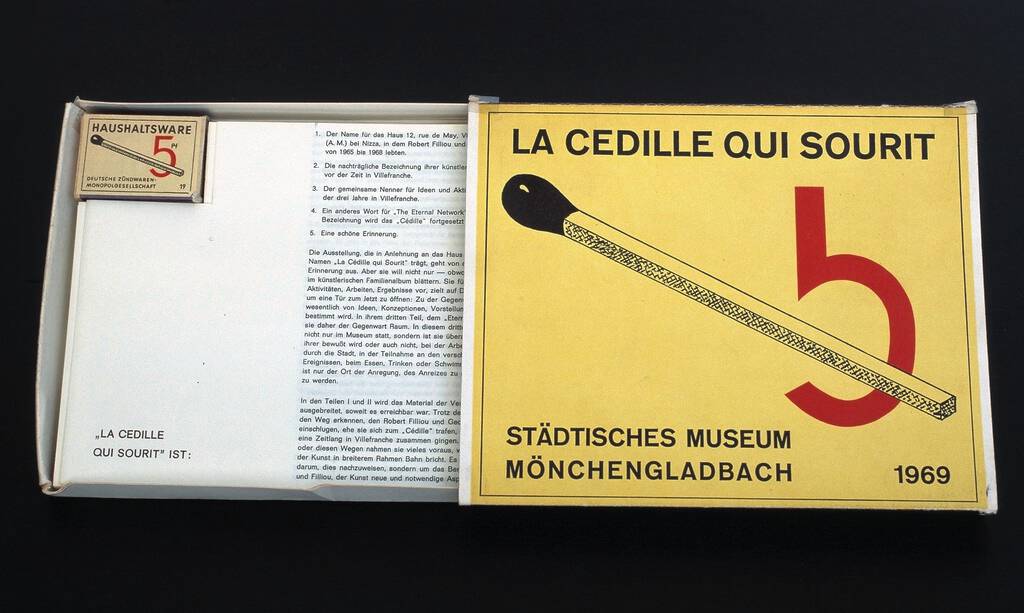

My favourite work, however, is the La Cédille qui sourit, produced for a 1969 exhibition of the same name at Städtisches Museum, Mönchengladbach:

From notes about the piece in the M HKA Ensembles collection:

The choice of the dimensions of this box was part of the Städtisches Museum catalogue editing policy and the idea of the matchbox extra large came from the director of the museum Johannes Cladders. The box contains a text by Johannes Cladders, a list of works by Filliou and Brecht from before their collaboration, a list of their works made during their stay in Villefranche and the workingspot ‘La Cédille qui sourit’ (1965-1968) and some iconogeaphic cards with the headmark of ‘La Cédille qui sourit’ and some invitations to participate in the making of an anthology of jokes by returning postcards.

This is a piece that demands an homage, and so I set out to create one this weekend. This is what resulted:

I printed fifty 90 mm by 55 mm cards on white coated cardstock (from the Bill & Gertie Campbell collection). The cédille itself is a hack–a beheaded “5” in 120 point Akzidenz Grotesk, printed in yellow ink from Southern Ink in Austin, TX. The text is printed in Southern Ink “dense black” in the 10 point sans serif face I picked up at the Museum of Printing last month.

If you would like one, PayPal me postage ($2 CAD for Canada, $2 USD for USA, €2 for international) and I’ll pop one in the mail to you.

I am

I am

Comments

Seems like the 69 exhibition

Seems like the 69 exhibition also used a headless 5 as ç

I didn’t notice the fully

I didn’t notice the fully-formed “5” on the small interior matchbox: thanks for pointing it out.